|

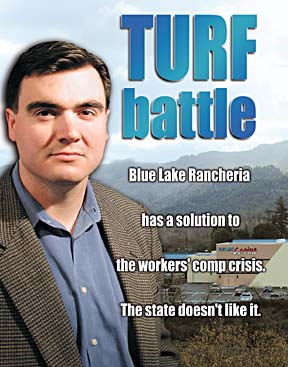

by HANK SIMS TO HEAR ERIC RAMOS TELL IT, HE JUST WANTS TO HELP. His fellow Californians, employers and employees alike, are suffering. The capable young man, who parlayed a business degree from Humboldt State into a series of high-powered jobs in the Silicon Valley tech industry before returning home to serve as the Blue Lake Rancheria's chief financial officer, wants to offer the state economy relief from what is probably one of its biggest difficulties right now -- California's workers' compensation crisis. "Our position is that the state has a problem, and we have a solution," Ramos says. "I would prefer that the state of California's system worked well, and we didn't even have this business." As owners of the Blue Lake Casino [photo below right] , as well as a number of smaller businesses, the 50-member Blue Lake Rancheria was already a large employer in Humboldt County. And because federally recognized Native American tribes are, at least in theory, regulated only by the federal government, the rancheria is not required to provide California's workers' compensation insurance to its employees. (Freedom from state regulation also explains why smokers can still practice their vice inside local casinos.) Instead, the rancheria has its own system of insurance for on-the-job injuries. The tribe has thus largely been shielded from the spiraling rate hikes in workers' comp coverage that have plagued California businesses over the last few years. California business owners now pay the highest workers' comp premiums in the nation -- over twice the national average. The average cost of a policy has doubled and redoubled in recent years. There are various explanations for the crisis -- the legacy of deregulation, over-generous benefits to injured employees -- but there is a near-unanimous consensus that the system needs to be dramatically revamped.

Partly for research purposes, Ramos says, he asked an insurance agent to estimate what a standard workers' compensation policy would cost the rancheria. That's when the suffering of his fellow businessmen -- the ones outside the tribal system -- really hit home. "I got sticker shock," Ramos says. So Ramos came up with an idea. How about a staffing company -- a temp agency -- that could lease employees to employers? Because the tribe operated outside of state regulation, it would not be required to pay the skyrocketing costs of workers' compensation. Savings would be passed on to employers, and the tribe could still make a decent profit. "We sit down and review new business opportunities all the time," Ramos says. "Sequoia Personnel [a local temp agency] has a staffing company in Eureka -- so, why not?" Ramos took the idea to the rancheria's business council, which, in May, approved the creation of the new company, Mainstay Business Solutions. Their timing, evidently, was right. What Ramos says he had initially envisioned as a much smaller-scale enterprise exploded. Big money At its height, according to Ramos, Mainstay was the employer of record for about 19,000 workers throughout the state. It had acquired satellite offices in the Sacramento and Los Angeles areas. The rancheria was netting $200,000 per month from the business. All within the space of a few months. That was before Nov. 7 -- before the state of California stepped in and threatened to shut down one of Mainstay's clients, a chain of International House of Pancakes restaurants in the Central Valley that had turned all its employees over to the tribal company. (The local chain of Denny's restaurants, which were briefly shut down by the state for workers' comp violations last month, was in talks with Mainstay but never actually contracted with the company.) In essence, it was a declaration of war against Mainstay by a government that insists it has the right and responsibility to ensure that all workers in the state -- all the ones who don't work on tribal land, at least -- are covered by state-approved workers' comp insurance. And while Ramos says that the insurance Mainstay offers in place of workers' comp is "as good or superior" to traditional coverage, the state maintains that the company is on the wrong side of the law. One state official vowed to prosecute companies that contract with Mainstay and questioned whether employees who filed legitimate claims would receive the financial awards they deserve. Ramos is undaunted. Mainstay has taken the fight back to the state, filing a lawsuit that argues that its actions infringe upon the tribe's sovereign status, and demands that the state back off. And while Mainstay itself has scaled back a bit -- Ramos says the company is down to 10,000 employees -- it is still very much in business, and with its employees covered by the cheaper tribal insurance in place of workers' comp. The business will be around, he says, at least until the state gets its own system under control. Nicholas Roxborough, a leading workers' compensation attorney who has been retained by the tribe, says that instead of attacking Mainstay, the state should be encouraging it and studying it for solutions. "You listen to [state Insurance Commissioner] John Garamendi -- he's been quoted as saying the system is broke, dysfunctional, it needs total revamping," he says. "Here's something that could be a pilot program." A broken system It would be hard to find someone in state government who wouldn't concede Ramos and Roxborough one point: The state workers' compensation system is broken. Probably just about every California business owner has their own story to tell about how the skyrocketing cost of workers' compensation insurance has impaired -- or, in some cases, destroyed -- their business. According to the California Workers' Compensation Insurance Rating Bureau, which keeps track of rates for the industry and the state, the average cost of a policy rose by 250 percent between 1999 and the start of 2003. For many local employers, those numbers seem conservative. Bruce Hamilton, CEO of Arcata manufacturing firm Wing Inflatables [photo below left] , says that his company is now paying twice what it did last year for its manufacturing employees -- an increase of $60,000 per year, with greater hikes promised in the future.

"You have to think that way," Hamilton says. "If we have another big expansion, do I want to buy another building in California? Or do we want to look at Nevada, or Tijuana? You try so hard to be efficient. You try so hard to save $100 here and there. Then, all of a sudden, you get hit with a $5,000 [monthly] increase, mandated by the state." Hamilton says that a substantial portion of Wing's current workers' comp expenses come directly from an experience with a former employee three years ago. This employee began to complain, Hamilton says, of a "vague hurt" in his upper extremities. The employee filed a workers' compensation claim -- even though, Hamilton says, doctors never identified the injury, and never tied it directly to the work the employee performed. Nevertheless, the former employee is in the process of negotiating a settlement with the company, and the claim impacts Wing Inflatables in the form of higher workers' compensation premiums. "This one incident, which was never precisely diagnosed, is costing Wing Inflatables $25,000 this year," Hamilton says -- money down the drain for the company, the expense of which must either be passed on to his customers or taken out of the bottom line. To Hamilton -- and, judging from comments made at a recent meeting of the county's Workforce Investment Board, many other local employers -- California's system gives far too much benefit of the doubt to claimants, making it all too easy for dubious injuries to win large settlements in court. "Say I hire someone -- they may have knitted for 50 years," Hamilton says. "They sit down and type for two weeks, develop carpal tunnel syndrome, and I'm responsible." Multiply such claims across the state, Hamilton says, and you have a thumbnail sketch of the crisis. The man in charge of the system, Insurance Commissioner John Garamendi, has a more nuanced view. In recent letters to employers and insurance companies, Garamendi has laid much of the blame for the skyrocketing premiums on the deregulation of workers' comp insurance in 1995. Insurance companies were allowed to set their own rates. An ensuing price war drove many companies out of the market, or out of business, with those left having to jack up premiums to cover their losses. Nevertheless, Garamendi says that fraud in the system is rampant. The commissioner has made attacking fraud one of his priorities for 2004, and has proposed closer ties between the state and local law enforcement agencies as a way to combat the problem more effectively. "The current culture of California's workers' compensation system is one where abuse and fraud are widespread and serve as a cost driver in the system," Garamendi wrote in a recent memo to state legislators. "This culture must change." [photo below: City of Blue Lake]

Ramos and Roxborough see Mainstay as providing the kind of change the commissioner is looking for. The tribal insurance policy -- which is backed by insurance giant AIG -- is in some ways closer to the kind of workers' compensation system offered in other states, such as Nevada or Arizona. According to Ramos, it removes large amounts of red tape from the equation. "We don't have to play by the state's rules," he says. "We're outside that. Because we can cut out some of the bureaucracy, we can save some dollars." Ramos estimates that for this reason, the Mainstay program can reduce employment costs by an average of 30 percent. Ramos maintains that Mainstay's insurance -- called an "occupational injury indemnity policy," to distinguish it from workers' compensation -- provides benefits for injured employees that are "as good or better" than workers' compensation. He says that the few injury claims that the company has had since its founding have been handled expeditiously, and all parties have been satisfied. But the system differs from the one mandated by the state of California in several important respects. Under workers' comp, the injured party has the option of choosing a doctor, or seeking several different medical opinions as to the cause or extent of an injury. With Mainstay, the injured must choose one of the doctors approved by the program, and the number of different opinions that one can get is limited. "That's one of the aspects we would promote as a fix to the system," says Ramos, who says that "doctor shopping" is one of the leading causes of fraud -- less scrupulous doctors may be too liberal with diagnosis and treatment. Roxborough says that the doctors blacklisted by the program amount to only 1 percent of the total number practicing in California -- in other words, there is no attempt to "stack the deck" by putting only industry-friendly doctors on the list. "When you get injured at Mainstay, you can choose from between 30,000 and 40,000 doctors in California," he says. The larger difference between the two systems has to do with how disputes over benefits to injured workers are settled. Under workers' comp, the employer usually pays all attorney fees. The Mainstay program, on the other hand, insists that if injured employees wish to dispute the size of their awards, they must pay their own legal fees. In addition, disputes are not settled in the state's legal system, but the Rancheria's tribal court. Though it sounds exotic, Ramos notes that tribal court is just as "regular" as the state -- it is an established area of jurisprudence. In the court, legal professionals -- often retired judges -- are hired for a day or two to run its proceedings, whenever a sufficient number of cases have come together to warrant a court. In sum, Ramos says, the Mainstay system is something of a return to the original, cooperative intent of the state's first workers' compensation law, passed in 1913. At the time, litigation between employers and employees over who would bear the financial brunt of on-the-job injuries was rife -- the workers' comp insurance system was supposed to be a "no-fault" solution that would reduce the number of legal disputes by assuring that injured workers would be taken care of. That's why Ramos bristles when he hears critics fault the Mainstay system because Mainstay workers don't have recourse to the state's standard dispute resolution system. "I would make the same argument about state of California workers," he says. "They don't have recourse to our system."

Fighting a scam Jerry Whitfield, assistant counsel for the Compliance Bureau of the California Department of Insurance (CDI), is not too convinced by these arguments, to say the least. Yes, he acknowledges that ever-growing workers' compensation premiums are hurting state businesses, but although he never says the word he makes it clear that he believes Mainstay is little more than a scam -- one that his department has pledged to fight. "It's a pitch," Whitfield says. "When the employer asks the magic question, `How can we do this? How can this be such a wonderful plan?' They hear, `Well, it's because of Indian sovereignty!' `OK, sign me up!'" Whitfield is speaking not so much of Mainstay itself, but of insurance brokers and agents who allegedly misrepresented the Mainstay program to their clients. One aspect of the state's crackdown on Mainstay is focused on removing or suspending the licenses of several insurance professionals who the CDI says marketed the Mainstay program as legitimate workers' compensation. The CDI, along with an allied agency, the California Department of Industrial Relations, is forced by circumstances into taking on Mainstay by attacking its edges -- insurance agents who promote the program, businesses that sign up for it -- because as a sovereign entity, the Blue Lake Rancheria cannot be sued by the state. In the future, though, it may be more difficult for the state to find targets in this battle. One of the ways Mainstay grew so quickly was by developing relationships with larger, more established staffing companies -- which, in addition to running temp agencies, operated as "professional employer organizations," or PEOs. A PEO's business is to be the nominal employer of other businesses' workers -- the PEO takes care of a company's payroll, insurance and other human-resource related issues in return for a flat payment. The PEO business was a natural one for Mainstay to get involved in; by being the nominal employer of another company's workers, the rancheria could pass on its cheaper workers' comp to all kinds of businesses, making a profit in the meantime. Whitfield said that the fit was natural for the PEO industry, too. "A lot of the PEOs that are providing coverage to their employers through traditional, acceptable means lost their coverage," he says. "Lo and behold, one of the PEOs got hold of the Mainstay program and they signed up their employers. They literally, overnight, switched their workers' comp providers from XYZ insurance company to Mainstay." It was one such arrangement -- at the IHOP chain in the Central Valley -- that became the state's first target against Mainstay. All of the employees in the eight-restaurant franchise chain were, at least on the books, employed by the rancheria. Neither the owner of the chain nor, of course, Mainstay, had taken out workers' compensation insurance for those employees. After the state threatened to shut the chain down -- and fined it $100,000, which Mainstay was contractually obliged to pay -- the owner of the business put all his employees back on his own books, and acquired workers' comp. The state based its shutdown threat on the fact that though Mainstay was technically the employer, the business owner, as a "secondary employer," also had the responsibility to make sure his workers were covered with regular workers' comp insurance. Ramos says that the experience was part of the company's growing pains, and that Mainstay is now out of the PEO business. He says that Mainstay now only represents temporary workers -- about 10,000 of them. The rancheria and its attorneys argue that legally, then, there is no longer any question of a "secondary employer," as there is with a PEO. "In staffing, where you are simply putting a temp out there, the [company that] sends the person to the place of work is the sole employer," Roxborough says. Whitfield disagrees, but acknowledges that the issue will have to be decided in court. Nevertheless, he pledged that his office would continue to fight to put Mainstay employees back into the workers' comp system. "The insurance commissioner understands the difficulty employers have in securing affordable workers' compensation coverage, given the current market conditions," he says. "However, they have the responsibility to ensure that coverage for their employee. The employees are the ultimate victims here. Remember, if the coverage appears too good to be true, it probably is." And the idea that Mainstay can serve as a sort of pilot program for the reforms everyone knows the state needs? "They should talk to the Legislature then, shouldn't they?" Whitfield responds. A history of persecution In the lawsuit Mainstay filed against the state late last month, Roxborough provides a long, detailed discussion of the laws regarding regulation of Indian-owned businesses -- all to ram home the point that the state has no legal standing in its fight against Mainstay's refusal to buy workers' comp. Whether tribal employees are Indians or not, he argues, or whether they work on tribal lands or not: The law is unequivocal. Roxborough includes in his suit a brief history of the rancheria -- how it was established as a refuge for the descendents of the Wiyots who had survived the Indian Island Massacre -- and, in speaking, he gives the impression that the state's battle against Mainstay is a result of continued discomfort with the principles of Native American sovereignty. "It's what Indian tribes are used to," says Roxborough. "They go to the government, they present a new program. What happens? They get attacked. To them, it's business as usual. They get frustrated." JeDon Emenhiser, a professor of government and politics at Humboldt State who has studied questions relating to tribal governance, says that the Mainstay case may ultimately have to be decided by the federal government. "The Supreme Court has said that Indian tribes possess those powers that are residual -- that is, what's left after Congress has taken rights from them," he says. "The dispute may ultimately be between California and the U.S. Congress over what rights the tribes will be given." While the suit proceeds, Mainstay is still in business and is still making money for the rancheria. Ramos says the tribe needs the income -- it must support its governmental structure through its business activities, and it makes regular substantial donations to the community, benefiting Indians and non-Indians alike. And while he says he does not wish to deride the Department of Insurance, like most employers he had heard the recent news on workers' comp reform. Insurance Commissioner Garamendi had been saying for months that recent legislation should result in a 15 percent decrease in rates; two weeks ago, when the new rates came out, it turned out that the cut would be only 2.9 percent. "Two point nine percent," says Ramos. "That's not meaningful reform. That's a pittance. That's a joke." MAINSTAY BUSINESS SOLUTIONS WEBSITE

Comments? © Copyright 2003, North Coast Journal, Inc. |

![[photo of Blue Lake Casino]](cover1218-casino.jpg) Ramos says that the situation, almost unique to

California, got him thinking about the differences between the

state's system and the tribe's. "Why does [our] system work

better than others? Or not work better than others?" he

asked himself.

Ramos says that the situation, almost unique to

California, got him thinking about the differences between the

state's system and the tribe's. "Why does [our] system work

better than others? Or not work better than others?" he

asked himself.![[photo of Bruce Hamilton in factory]](cover1218-warehouse.jpg) Hamilton

isn't sitting back and shrugging his shoulders at the costs.

In a Dec. 10 letter to Assemblymember Patty Berg, Hamilton drew

a line in the sand: Lower workers' compensation costs, he said,

or our company -- with its 60 well-paid employees -- will have

to "seriously consider" moving out of the state.

Hamilton

isn't sitting back and shrugging his shoulders at the costs.

In a Dec. 10 letter to Assemblymember Patty Berg, Hamilton drew

a line in the sand: Lower workers' compensation costs, he said,

or our company -- with its 60 well-paid employees -- will have

to "seriously consider" moving out of the state.![[photo of city of Blue Lake]](cover1218-bluelake.jpg) Less red tape

Less red tape![[Graph showing the Average Insurer Rate Per $100 of Payroll, insured employers as of 3/31/2003: 1993: $4.40, to a low of $2.27 in 1999, and rising upward to $5.85 in Jan.-March 2003.]](cover1218-graph.jpg)