|

Building a dikeby KEITH EASTHOUSE

Seeking JusticeIT WAS A CURIOUS SIGHT IF YOU STOPPED TO think about it. On one side of Freshwater Creek, right in front of where Jerry Gess was standing, the bottom was covered by a thick belt of sediment. On the other, lying right alongside it, the bottom was a good deal rockier. Why the difference? The answer could be found simply

by tracing the slug of sediment with your eye upstream about

10 feet to a tangle of brambles -- the mouth of McCready Creek.

It wasn't raining, so McCready was flowing quietly and relatively

clearly. But, as Gess said, you should have seen it a few days

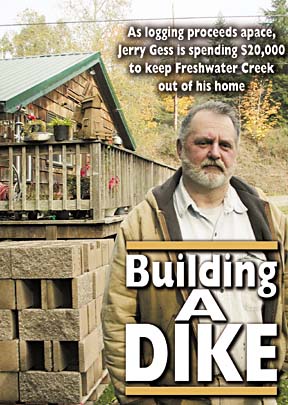

before. "We got just a little bit of rain and [McCready} was just pumping mud out," Gess said. "See that?" he asked, pointing at the muddy underwater carpet. "Fish can't spawn in that." Not coincidentally, the McCready Creek watershed, part of the larger Freshwater basin, has been the site of recent logging activity by the Pacific Lumber Co. "I don't know what else to blame it on," Gess said. "If you tear up the ground, the ground will wash downhill." [Jerry Gess. Photo by Bob Doran.] Gess, a burly 61-year-old mechanic, didn't seem too perturbed. But then erosion from PL timberlands upstream of his 1.5-acre property along Freshwater Road has been obvious for years. Standing on an uneven bulge in the riverbank adjacent to Freshwater Creek, Gess declared that this used to be where McCready fed into Freshwater. "This was the mouth for my whole life except for about the last five years," he said, explaining that sediment deposition has literally moved the creek's terminus several feet upstream. He started talking, as many longtime Freshwater residents are apt to, about silted-in swimming holes and disappearing fish. "You used to be able to catch fish with your hands," he said. "It would reek during the spring; carcasses would be lying in trees when the water would go back down." And he spoke of an old well that used to provide drinking water to the neighborhood. "That got filled up with sediment," he said, adding that the operator of the water system sued PL for damages. He walked up the muddy bank and onto the expanse of grass that spreads out from his green-roofed, wooden house. The small field is a bit lumpy and wavy, which is what you'd expect for a place where silt has been repeatedly deposited. Gess's property, which extends across both Freshwater and McCready creeks, has been inundated multiple times over the past eight or nine years, and his garage has been flooded on three occasions. But the house itself has been spared, although during torrential rains at the end of last December, rains that put his deck under 4 inches of water, Freshwater Creek came "this close" to spilling in. That's what decided it for him. Four years ago his annual flood insurance tripled to $1,500, but he took that in stride. The scare he got at the end of last year, though -- when he raised things like his refrigerator and his washer and dryer as the floodwaters rose outside -- made him realize he needed to be better prepared this winter. The solution he came up with would seem a bit novel. It's not that unusual out in Freshwater for someone to raise his or her home. It is considerably rarer, perhaps unprecedented, to do what Gess is doing: building a dike. About a week before Thanksgiving, he had a trench dug around two sides of his home -- the south side to protect it from Freshwater Creek, and the east side to guard against McCready. Stacks of cinder blocks that will serve as the building material for the dike stood in his yard, along with piles of rebar. When it's done, the L-shaped concrete retaining wall will be 151 feet long, and 5 to 6 feet high. Call it the great wall of Freshwater. In addition to landing him on the cover of this week's Journal, the construction project -- which is costing Gess $15,000 to $20,000 -- was featured in a recent broadcast by a Bay Area television station. (The main subject of the segment was the attempt to recall District Attorney Paul Gallegos, whose controversial lawsuit against Pacific Lumber has enraged the company's supporters.) He hasn't minded the attention, although he voiced concern that his words might get misconstrued. "I'm not anti-PL by any means. I feel almost guilty saying what I feel. Every time I see a logging truck I think, `There's a guy feeding his family.'" At the same time, when it comes to logging in Freshwater, which has been intensively cut over the past 15 years, Gess thinks enough is enough. At the least, he thinks PL should be prevented from harvesting during the rainy season, when the flooding potential is greatest. At the most, he thinks logging in Freshwater should be stopped altogether. "The only way to clean this up is to leave it alone and let 50 years go by," Gess said. A watershed meeting?If logging continues in Freshwater at the pace of the recent past, scientists -- although perhaps not those with PL or the California Department of Forestry -- may soon be saying something similar. Take a pair of studies that have come out in the past 11 months. Commissioned by the North Coast Regional Water Quality Control Board, a state agency charged with protecting water resources, the twin reports vindicate what the board's scientific staff has been saying for years: The rate of cutting in the five watersheds on Pacific Lumber property that have been declared "sediment impaired" under the Clean Water Act -- Freshwater, the Elk River watershed immediately to the south, and Stitz, Jordan and Bear near Humboldt Redwoods State Park -- is too high. The result has been deteriorating water quality and worsening flooding as streams and creeks fill in with sediment. Both reports were done by the same team of seven outside scientists, a group dubbed the Independent Scientific Review Panel, or ISRP. Its members, chosen by Pacific Lumber and its critics in a formalized negotiating process, included Robert Twiss, an emeritus professor of environmental planning from the University of California at Berkeley; Fred Everest, a fisheries biologist from the University of Alaska and a Humboldt State University graduate; and William Haneberg, a geologist from Washington state. The panel's first report, issued last December, said something Pacific Lumber didn't want to hear: The model it uses for estimating sediment yield from logging activity, a key factor in determining appropriate harvest rates, is unworkable and prone to bias. The second report, released in August, said something else the company didn't want to hear: Its "habitat conservation plan" (HCP), which guides logging on the company's property for the next 50 years and was a key element in the 1999 Headwaters deal, does not sufficiently protect water quality. The question now is what, if anything, the seven-member water board is going to do with the reports. That could very well be decided at the board's next meeting, on Dec. 2 and 3, at the River Lodge Conference Center in Fortuna. The second day of the meeting will be devoted to the ISRP reports, and it is likely to be a stormy affair -- PL loggers will no doubt be out in force, particularly since the conference is practically in the company's backyard. So will residents of Freshwater and Elk who are fed up with the flooding. Standing with them will be environmentalists from the Humboldt Watershed Council and the Environmental Protection Information Center -- both of which have long been thorns in PL's side. Frank Reichmuth, assistant executive officer for the board's staff, said last week that a staff report being made available to board members over the Thanksgiving holiday will pose a fundamental question: Given the ISRP reports, "Do you feel that additional controls on rate of harvest and sediment production [in the five watersheds] are necessary?" If the answer is no, then the status quo, which does not significantly curtail the company's operations in the five watersheds, would be maintained. In the event that the answer is yes, the report lays out three options:

Presently, such restrictions, known as "waste discharge requirements," apply to a limited number of timber harvest plans (THPs) in Freshwater and Elk, the two sediment-impaired basins that harbor significant populations of people.

This would be a bold move, but activists fear Pacific Lumber would be able to wriggle out of it. Mark Lovelace of the Humboldt Watershed Council said that if the board opts for this course, it has to word the order as strongly as possible and leave no loopholes. Otherwise, the company is not likely to stop cutting. "All the [scientific] information says that timber harvest activities result in discharge," Lovelace said. "But PL will say they're not discharging, that they're just dropping trees and they'll keep operating like normal. "They'll try to keep the burden of proof on the water board to prove that dropping trees constitutes a discharge," Lovelace added.

The forestry department has long had sole authority to approve or reject THPs; the water board's power has extended only to discharges from such plans. But a bill signed by former Gov. Gray Davis in the waning days of his administration gave water boards throughout the state the power to veto logging projects that pose an undue threat to water quality. Any veto issued by any of the nine regional boards in the state can be appealed to the state board, and all are comprised of gubernatorial appointees, so politics has hardly been taken out of the process. It was not lost on activists that Davis recently reappointed to the North Coast regional board Daniel Crowley, a Santa Rosa lawyer who engineered the firing a few years ago of Lee Michlin, to this day one of the most aggressive heads of the water board staff when it came to protecting water resources from logging impacts. Considering that the agency spent about $200,000 on the two ISRP reports, one assumes the board will take some sort of strong action. But then that was also widely assumed 19 months ago, in April 2002, when a stormy, two-day meeting in Eureka on whether to impose sweeping sediment discharge restrictions on Pacific Lumber timber operations ended inconclusively. Hard-hittingThe reports stem from that same spring, when, under the water board's aegis, an effort was made to mediate the differences between Pacific Lumber on the one hand, and activists and residents of Freshwater and Elk on the other. The mediation, led by the Berkeley-based facilitation group, Concur, Inc., collapsed after just a few meetings. The sticking point? Rate of cut. Activists and residents wanted it dramatically lowered from the levels that were in effect then and still are today: 500 clear-cut equivalent acres in Freshwater and 600 in Elk. (PL cannot clear-cut any more land than that, though it can log more acreage if it uses lighter logging methods, such as selective harvesting.) PL didn't want to talk about rate of cut, considering it a matter between the company and its regulator, CDF. The way out of the impasse, both sides eventually agreed, was to have a group of independent scientists review all the studies that have been done since the five basins were declared sediment-impaired -- and there have been plenty -- and essentially make sense of all the conflicting data. Both sides chose the panelists, and questions were crafted that the panel was to be charged with answering. The panel's findings include the following:

The irony here is that PL frequently points to such efforts to justify continued logging.

This method, employed by Leslie Reid of the Arcata-based Redwood Sciences Laboratory, a research arm of the U.S. Forest Service, works precisely because it is relatively simple and does not rely on a slew of data. Pacific Lumber scientists have attacked it on that basis, but the ISRP report said the Reid approach is "fundamentally sound and at a level of data commensurate with the kinds and amounts of data that are available, or can be made available, in the near future." Pacific Lumber's approach, in contrast, relies on a host of esoteric data -- such as the rate of "soil creep" -- that are not known at this time or are difficult to know. Consequently, the modeler is forced to make a number of assumptions and subjective judgments, which, the panel said, makes it fairly easy to choose the desired outcome first and then make the model produce it. In other words, it isn't hard to cheat. This all may sound quite esoteric, and it is, but it's also a bit of a bombshell. Reid, for example, has calculated that if the North Fork Elk watershed is to begin recovery, no more than 39 acres a year can be cut. From 1987 to 1997, Pacific Lumber cut 504 acres per year in the 14,600 acre sub-basin, and today the company is cutting many times more acreage on an annual basis in North Fork Elk than Reid says is wise. Reid has never made a calculation for the allowable cut in Freshwater, but one researcher who employed her method a few years ago arrived at 80 acres a year. CDF allows PL to cut more than six times that much acreage annually.

PL had hoped their analysis would persuade CDF to relax the 500-acre ceiling, but the agency has decided to stick with it. The panelists found other flaws

with PL's analysis. For example, it presents data on harvest

rates from 1988 to 1997 that appear designed to hide the fact

that the cutting rate then was the highest in the history of

the watershed. (More than a third of the entire watershed, some

7,000 acres, was cut.) Road building rates were similarly cloaked,

the panel said. Attack modeGiven such findings, it shouldn't be surprising to hear that Pacific Lumber has come out against the ISRP reports with both guns blazing. After the first one was issued, the company criticized the panelists for failing to take into account the protective measures ensconced in the HCP. After the second one found the HCP lacking, former company spokesman Jim Branham got personal, saying that the study, and by extension the panelists themselves, lacked scientific integrity. "Their irresponsible conclusions reflect nothing more than uninformed personal opinion and conjecture," Branham said in a written statement. Branham also castigated the reports because the panelists, while they conducted site visits, didn't do their own field research. "No true science was conducted," Branham said. This was a puzzling criticism since all parties had agreed ahead of time that the panel would do a "review study" -- meaning an evaluation of existing research, not the generation of new data. Members of the timber industry, such as George Ice of the Corvallis, Ore., office of the National Council for Air and Stream Improvement, a forest products research group, and Roger Poff, a soils scientist, rallied behind PL, arguing that the ISRP had given short shrift to "mitigations" aimed at reducing erosion, such as replacing clogged culverts and storm proofing roads. The signatory agencies to the Headwaters Deal -- CDF, the state Fish and Game Department, and the National Marine Fisheries Service, which issued the federal permit that made the HCP possible -- also found the reports lacking. Bill Trush, adjunct professor in the fisheries department at HSU and a strong supporter of the ISRP reports, said that while mitigations can reduce sediment discharges, it is well known that they also "leak" sediment into the environment. The panelists, who said that the process of rehabilitating logging roads could send pulses of sediment into the environment, made a similar point. Trush also praised the panelists for pointing out the HCP's blindness to the cumulative environmental impact of logging both over time and space, and for addressing the one thing PL doesn't want altered: the rate of cut. Bill Snyder, CDF's deputy director for resource management, did not deny that the five basins studied by the panelists are in bad shape. "Clearly these watersheds are impaired and there are species that utilize these watersheds that are at risk." Snyder's solution? Adhere to the mitigation measures in the HCP, measures that he firmly believes are effective. But also rely on the "total maximum daily load" (TMDL) process, an effort to limit sediment discharges within an entire watershed. "One way [to reduce sediment discharges] would be to utilize the TMDL process and avoid operations within portions of the watershed where operations shouldn't occur." The TMDL approach could indeed lead to significant sediment reductions, but because it requires quantifying numerous sediment discharging sources in a given basin, it is not clear that it could take effect soon enough to spur the recovery of basins like Freshwater and Elk. To Ken Miller of the watershed council, opting for TMDLs would just be one more delay tactic. "All they need is three more years of delay and then they can say, `Oops, you were right [the rate of cut was too high], but now there are no more trees,'" Miller said. Miller said he wouldn't be surprised if the water board at next week's meeting called for pushing ahead with TMDLs for the five basins rather than directly trying to slow the rate of cut. That might not surprise Randy

Klein, either. But Klein, a local hydrologist, had this summation:

Given the ISRP reports, it's time for the water board to "take

a hard look at the rate of timber harvest" in places like

Freshwater and Elk. Flashy flowsWhen it comes to the water board, John Estevo [photo at left], a dairy rancher who owns 160 acres in the Elk watershed, isn't holding his breath -- although he thinks "public pressure is eventually going to force a change" of some sort. Like many of his neighbors, he's become resigned to the pitfalls of living downstream of a large commercial timber operation. He said that the logging has caused the Elk River to flow more irregularly; it's either flooding or it's a trickle. During the dry season, he used to depend on the river to irrigate his fields so his cows would have grass to eat. Now there's not enough water in the summer, so he has to bring in feed to make up the difference. Doing so cost him $3,600 this year, he said. Balding, 47 years old and a pilot, the slightly built Estevo has seen PL's timberlands from the air. But it was the flooding at the end of last year, the same flooding that led Jerry Gess to build his dike, that made him truly realize that things aren't getting better. That was the "last straw," Estevo said. Seeking JusticeFreshwater resident Jerry Gess, who is building a dike to protect his home from the flooding that plagues the logging-damaged watershed he lives in, is not limiting his actions to emergency construction projects. He's also turning to the courts. He's not alone. Fourteen other Freshwater residents, along with 23 who live in the Elk River basin southeast of Eureka, have joined in a lawsuit that seeks compensatory and other damages from the Pacific Lumber Co. Their basic contention is that the company's logging has, as the 59-page complaint filed in Humboldt County Superior Court in May phrases it, "put downstream residents at increased risk of harm and damage." The suit goes further, alleging

that Pacific Lumber suppressed information and provided false

information regarding the potential impacts of its logging "in

order to gain approval of the plans [from regulatory agencies]

and deceive downstream residents." It's that claim that

helps explain why the residents are seeking damages under the

Federal Racketeer Influenced and Corrupt Organization Act, better

known as the RICO statute. "The fraud was in not disclosing what they knew" during the THP approval process, the residents' lawyer, Bill Bertain [photo at right], said last week. PL spokeswoman Erin Dunn was reached late on Monday and didn't have enough time to formulate a response. Bertain has taken on Pacific Lumber before -- and achieved significant financial settlements. The first was a successful effort on behalf of PL workers to restore the company's pension fund. Most recently was last year, when the company chose to settle out of court with 22 Elk River residents rather than risk a trial in Humboldt County Superior Court. Prior to that, Bertain won a $3.3 million settlement for 33 residents of the tiny town of Stafford after a debris torrent roared out of Pacific Lumber timberlands and destroyed homes on New Year's Day 1997. Pacific Lumber's reaction has been mixed. After the Elk River settlement was announced last year, PL San Francisco attorney Edgar Washburn said, "Trials are always good to avoid. The resolution was one we think is fair." But last month, in a letter to company employees, CEO Robert Manne complained that residents had "extorted money from the company." As for the current suit, Gess, for his part, said simply: "If your actions create problems, you ought to be held responsible." IN THE NEWS | GARDEN | CALENDAR

Comments? © Copyright 2003, North Coast Journal, Inc. |