|

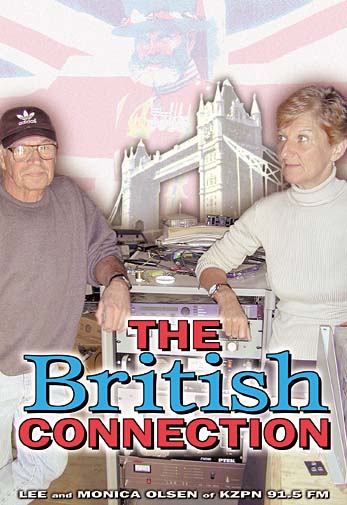

by ARNO HOLSCHUH SIDEBAR: BOB EDWARDS, VOICE OF NATIONAL PUBLIC RADIO ON A LATE AFTERNOON IN 1982, AS MONICA AND LEE OLSEN DROVE home in bad spirits along Old Arcata Road, a radio station was conceived. Monica, a British expatriate, said in an interview at her home that she was "totally homesick and complaining about it" that day. As her pining for the UK began to erode Lee's good mood, they started a tiff. "Lee snarled and said, `What would make you happy, then?'" Faced with the question of what she missed most, Monica "got snitty," as she put it, then decided on BBC 3 and 4, two intellectually stimulating channels of programming put together by the British Broadcasting Service. Lee's response has shaped the last 10 years of their lives. "Lee said something to the effect of, `Well, get off your backside and do something about it,'" Monica said. "No, no," Lee interrupted in an accent as clearly Chicago as Monica's is British, "What I said was, `Why the f*** don't you do it then?'" "To which I got all snivelly and said `Oh, I can't,'" said Monica. Lee, a radio engineer by trade, assured her that she certainly could and he would help. With that exchange, KZPN 91.5 FM was born. Can it really be that simple to start a radio station? The answer from both is an emphatic "No." They said that while it is neither expensive nor implausible, it requires lots of patience, hard work and sacrifice. Their reward is that they can broadcast their unique vision of what radio can and should be to the rest of us in the Humboldt Bay area. Monica and Lee were not new to public radio in Humboldt County. Both worked at KHSU on campus at Humboldt State University, Lee as an engineer and Monica as a volunteer DJ. From 1979 to 1984 Monica programmed classical music and children's shows. "It was the most wonderful training and very absorbing," Monica said. But she began to feel that some at the station were not receptive to classical programming. "There was a lot of fear toward classical programming, and that fear bred hostility," she said. Monica eventually left the station as part of a disagreement about the Texaco-Metropolitan Opera program, which broadcasts live opera every Saturday morning. "Unfortunately, I got involved in the politics of whether (it) was to be broadcast or not," she said. "It was their job to carry that program because they are the predominant public radio station in the area." (Eventually KHSU officials decided against carrying the program. Today the Texaco-Metropolitan Opera is carried by Oregon-based KSOR, available locally on 107.3 FM). It wasn't until 1992, 10 years after the Olsens' initial conversation, that KZPN started broadcasting. But the dynamic that was revealed in that conversation still powers the station today. Every single day Monica takes on the near impossible task of administering a 24-hours-a-day radio station by mixing BBC 3, BBC 4 and her own classical music programming with Lee handling the technical side. It is a labor (or is it labour?) of love for both Monica and Lee and a testament to the potential of two people with a lot of desire and a strong work ethic.

The station is unique on the North Coast. Because it is run solely by Monica and Lee, it has become a reflection of their personal tastes and beliefs about what radio should be. There are no commercials, underwriters or fund drives because the two plain don't like them. Monica never announces the name, composer or performer of classical music she plays, as she feels it would be distracting to people who use the station as background while they work. She preempts certain BBC programming that she deems "brainless room-temperature-IQ idiocy" but will tape and rebroadcast certain other programs. Underlying the programming choices is a sort of philosophy of radio. Lee said that they both believe "public broadcasting should be for the minority." He feels that commercial broadcasting serves the majority of people, giving them what they want to hear, leaving only a small minority underserved. That's where KZPN comes in. So what, exactly, will you find on KZPN that you wouldn't find anywhere else? Monica said her favorite programs (and therefore the ones assured to hit the airwaves) are the "Play of the Week," literary review programs like "Off the Shelves" and "Meridian Books," "Poetry Requests" (this elicited a frown and a loud snoring noise from Lee) and something called "People and Politics" -- "so you can hear how the English language should be spoken," said Monica. There's no doubt the programming is unlike that heard on any other station. As this story is being written, KZPN is broadcasting a report on the role of hand gestures in Indian and Cambodian sacred musical theater -- not exactly the stuff of top-40 radio. Other BBC programming includes shows like Alistair Cooke's "Letters from America" (at 10:45 a.m. Saturdays) and "The Alternative," a wide-ranging modern music program hosted by John Peel (Tuesdays at 8:05 p.m.). "Just a Minute," a quiz show that makes "Who Wants to Be a Millionaire?" look like kindergarten, exhibits classically dry British wit. BBC's full schedule can be found at its website, www.bbc.co.uk -- but Monica takes complete liberty of picking, choosing and shifting the time slots. Monica said the best thing she's heard lately was an interview with Gore Vidal. "The program started out by saying that when Vidal, known for his acerbic wit, was asked whether he believed in corporal punishment, he replied, `Only between two consenting adults.' And it just got better from there!" The ironic thing is that Vidal, an American author, was available only on British radio. It's not an isolated phenomenon, said Lee. "By choice, without government edicts, we are one of the most censored countries in the world." The BBC World Service news is Lee's favorite facet of KZPN, he said, because news in the United States is so poor. Monica's classical programming is also unlike that of the other classical music outlets in the area -- KHSU, KMUD and KSOR. She plays what Lee calls "high-class Muzak," classical music that isn't likely to interfere with the thoughts of those listening. "I'm not into educating people, challenging them. I get the impression that those who listen are of the mindset: `All right, I'm at work, I don't want to hear anything, but this music is nice when it is there.'" The idea of being nonintrusive is also behind her practice of not announcing what pieces she is playing. Monica said someone once told her that the music should all be announced. "And the person next to them happened to be an artist who listens to the station while he works. He said, `No, I don't think she should. I don't want the distraction.'" If it sounds nice to be able to design your own radio program filled only with the programs you want to hear, beware: Monica and Lee pay a price for their individualistic programming. They have to adhere to a merciless schedule that requires somebody to be at the station pretty much around the clock and they get zero financial compensation for their efforts. Take the problem of station identification breaks: Once every three hours, someone has to come on the airannounce the station's name and frequency. With a staff of one, that means that Monica has to get up once every three hours at night and spend a minute on the air. In the beginning, she said, she dragged a couch into the uninsulated studio and slept there. These days, she sleeps in her bed, but she doesn't get much sleep. At the time of the interview, she estimated she had gotten "between three and five hours of sleep per night in the past three weeks." "It gets difficult because people will call up and complain that a program is missing or its time has changed, or that the signal sounds bad. And some part of me just wants to say: `Shut up and leave me alone, I can't get you everything you want.'" The job sounds overwhelming, but Monica does have some help from Lee. He not only takes care of the technical aspects of the station but also sometimes takes over for Monica so she can have more than three continuous hours of rest. During the interview it becomes clear that he performs one other function as well: His caustic wit keeps Monica sane in the face of numerous obstacles. Asked at what point she thought she might actually get some quality rest, Monica answered somewhat despondently, "With any luck, I'll drop dead." "When were you planning on doing that?" Lee asks her with a straight face. Monica cracks a smile, then says, "Not this week. I guess I'm too busy." "You'd better not. I have plans, too," Lee says, his face turning into a smile. "Schedule it," he suggests. "Bloody selfish fellow," Monica replies -- without a trace of hostility and clearly in better spirits.

It also helps that the studio is located in a room added onto their house, so that Monica can move from station to home and back without having to get in her car -- or for that matter get dressed, as she points out. "I can walk in, walk out, make some tea, get something to eat, take a nap, walk around without any clothes on because it's a hot day ... and everybody else can mind their own business. "I couldn't bear it any other way." All that work precludes a paying job, and the station is run on such a tight budget that the couple ends up pumping their own money into it rather than the other way around. Lee works as a paid engineer for other local radio and television stations and earns enough money to allow Monica to continue her unpaid more-than-full-time job. Monica estimated that the station's annual budget was about $17,000 last year -- and that was a good year. The station has survived on as little as $14,000. That money is used to expand the station's library of classical music, pay a fee to be listed as a public radio station, and purchase and repair equipment. Monica said it was not at all uncommon for the transmitter to break down, or as she put it, "blow up." "It last happened just about four months ago," she said. KZPN is a low-power station with equipment that is, in radio terms, cheap to maintain, but the repairs put a constant strain on their budget. A new transmitter can cost $7,000, Lee said. At the very least, each "blow up" necessitates a trip to San Francisco for parts.

The Olsens' horse stands next to the sattelite dish The lack of funds isn't surprising, considering that the closest Monica or Lee get to fund-raising is mentioning on the air once in a while that they are non-profit and listener-supported and -- by the way -- do accept contributions. Both hate fund drives and steadfastly refuse to include any kind of advertising. Monica said she would "see the station go down rather than start advertising." Amazingly, people still do contribute. Monica said the way it usually works is that a listener will call the station and ask how on earth the station manages. "And we say that we manage because people call us up and ask how on earth we manage. Then we tell them that we accept contributions and they generally reply that their check will be in the mail." So far, that honor system has worked, but just barely. Monica said she can recall many occasions where she got "gut crunches" because the station had no financial buffer. "That's what I really hate, the feeling that something has to happen in the next 10 days or PG&E won't get paid. I don't like worrying about it." She estimated that about 400 of her listeners contribute on a regular basis but that many more are listening to the station without thinking about how it is supported. "What really frustrates me are the people who rush up, grab hold of me and say, `Oh, you do KZPN, I just love the station, I don't listen to anything else in the world, I don't know what I'd do without it.' Then they rush off." But for all of the frustration it causes her, Monica said she was still glad that she started the station. "It was something I believed in, to show people it could be done, to show them that if you don't like it you can do something about it." Editor's note: For any KZPN listeners feeling particularly guilty, Bob Edwards, the voice of National Public Radio

At one point Edwards spoke about the influence of the British Broadcasting Corp. In the U.S.-sponsored NPR. "The BBC was our model when we began," said Edwards. "They are what public broadcasting ought to be. They're much bigger, their budget is huge, they've been at it so much longer. Of course they were serving an empire on which `the sun never set.'" Edwards tends to downplay his own importance and distances himself from "the suits" who run NPR by describing himself as "a grunt" and "just another union shop employee." (He is in fact vicepresident of the American Federation of Television and Radio Artists, the broadcast workers' union.) But he is far more than just a voice reading news scripts. He has helped shape the direction of the magazine programs. When Edwards, a trained newsman, came to NPR to work on "All Things Considered," the focus was much different. "We were not a news organization, we were a magazine of the arts," he said. "The arts people ruled. We only had maybe five or six reporters. We had to rely on local stations for news and they had no money. They would send us stories about quilting bees and dulcimer makers. Then one by one the newsies came aboard." NPR's ongoing dedication to news sets it apart from most of modern American radio. "Commercial radio, which used to do a lot of news, doesn't any more. They were largely deregulated and they're no longer required to do public service programming, so they don't. "They fired their news staffs. News is very labor intensive. It's expensive to do. They got rid of all those people and now they either take a syndicated service or they don't do anything at all. Most of them don't even give you headlines on the hour. "So it's fallen to us to fill the vacuum and we have, handsomely. It's bad for radio, but it's great for NPR because more people searching for news on the radio find us. Our audience has grown. "NPR has an audience the others would kill to have -- an audience with a pulse, people who are involved with the world, people who care. And it's not an upscale audience, it's one that includes blue collar people and bank clerks." The future of NPR? Edwards says "the suits" have set expansion into new delivery systems as a high priority and "much to the chagrin of some of us at street level" have invested a lot of time and money in the Internet. "They'll stream all of the programs from NPR except for 'All Things Considered' and `Morning Edition.' The stations don't want them on there," he said. NPR has also signed on with satellite radio. "It's a new kind of radio, direct satellite broadcasting. Your cars will be equipped with satellite receivers. There will be no stations; it's direct to your car so you can follow the same channel all across the country. "We will be on the Sirius System. They'll have 100 channels, NPR will be on two. Sirius' rival is something called XM. Their slogan is, `First there was AM, then there was FM, now it's XM.' "It will be narrow-casting and the music channels will be particularized. It won't just be reggae, it will be a particular kind of reggae. There's one channel that will be NASCAR, if you can imagine that on the radio, `Zoommm, zoommm.'" --- reported by Bob Doran Comments? E-mail the Journal: [email protected] © Copyright 2000, North Coast Journal, Inc. |

![[photo of Monica Olsen]](cover1123-monica.jpg) Monica Olsen at the KZPN airboard in the radio studio next door to their Bayside home.

Monica Olsen at the KZPN airboard in the radio studio next door to their Bayside home.![[photo of Lee Olsen]](cover1123-lee.jpg) Lee Olsen just inside the station door.

Lee Olsen just inside the station door.![[photo of horse]](cover1123-horse.jpg)

![[photo of Bob Edwards]](cover1123-side-bobE.jpg) Bob Edwards, the voice of National Public Radio's most popular show, "Morning Edition," visited Humboldt State University last week. In between a morning session with journalism students and an afternoon speech to more than 300 fans, he recorded a few public service spots for KHSU-FM 90.5, which sponsored his visit.

Bob Edwards, the voice of National Public Radio's most popular show, "Morning Edition," visited Humboldt State University last week. In between a morning session with journalism students and an afternoon speech to more than 300 fans, he recorded a few public service spots for KHSU-FM 90.5, which sponsored his visit.