|

by KEITH EASTHOUSE JERRY HAVENS, A UNIVERSITY of Arkansas chemical engineering professor, is busy these days. More than busy. Swamped. Ever since he wrote an article for the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists on the possible consequences of a terrorist attack on shipments of liquefied natural gas, he's drawn attention. "My phone has been ringing off the hook on the subject," Havens said earlier this week. Part of the reason is simply the post-9/11 zeitgeist -- anything terrorist-related is news, and there's no question that tankers carrying LNG, as the supercooled fuel is called, could be an inviting target. (If ignited, LNG burns much more rapidly and intensely than oil or gasoline.) Then there is the timing -- Havens' article appeared in the magazine's July/August issue, just a few weeks after Federal Reserve Chairman Alan Greenspan went before the House Energy and Commerce Committee and called for a sharp increase in imports of LNG to help ensure the ongoing recovery of the U.S. economy. "Access to world natural gas supplies will require a major expansion of LNG terminal import capacity" in the United States, Greenspan told the committee. A third reason Havens' story struck a nerve is that LNG projects are popping up all over the place -- the energy industry, responding to rising demand for natural gas due to environmental concerns about other energy sources, has proposed as many as 20 new LNG marine terminals in the United States. Excluding one that opened in Puerto Rico last year, there hasn't been a new terminal built in the United States in over 20 years. There are only five LNG terminals in the country, all but one of them located on the Eastern seaboard or along the Gulf of Mexico. (A terminal on the Kenai Peninsula in Alaska is the only one that exports LNG -- to Japan.) Seven of the new proposals are "well advanced with pending federal approvals," according to a recent study prepared for Congress. Only one of those would be located on the West Coast, actually about 20 miles off the coast, near Oxnard in Ventura County. But with abundant natural gas supplies in the Pacific Rim, in places such as Indonesia, Australia, and Central and South America, the energy industry seems determined to open an LNG terminal somewhere in California, Oregon or Washington. A proposal by Bechtel and Shell Oil to build an import terminal on Mare Island near Vallejo was moving forward nicely last year -- before it ran into a wall of opposition from community members concerned in part about the safety hazard. (See sidebar.) Shell has pulled out of the project, while Bechtel says it's on hold. Meantime, as many in Humboldt know, the San Jose-based energy company Calpine is exploring the possibility of constructing an LNG import terminal on the Samoa Peninsula, most likely at the 80-acre, defunct Simpson pulp mill site.

Samoa Peninsula resident Dick Lindstrom stands at the proposed Calpine site at the old Simpson pulp mill. Like the proposal by an Alaska businessman to haul millions of gallons of water from the Mad River to points south in giant bags, the proposal floated by Calpine is of such a scope that some are having trouble taking it seriously. The tankers, 900 feet long by 150 feet wide, would be the largest ships ever to enter Humboldt Bay. These behemoths would become a familiar sight -- Calpine says they would come in at the rate of two per week. Their hazardous cargo, 33 million gallons worth per ship, would be pumped into storage tanks -- probably two in number -- standing 150 feet tall and 250 feet across. A "regasification" plant would warm the fuel, which clocks in at a chilly 260 degrees below zero in its liquid state, back into its normal vapor form. The gas would then be sent via a new, 36-inch pipeline under Humboldt Bay and out to Red Bluff, a distance of 155 miles, where it would feed into the Central Valley's energy grid. It would also power a new 220 megawatt power plant that would replace the aging PG&E facility that the Humboldt Bay region still depends on. The entire construction project, which would include building a new dock, is likely to take three years and cost $750 million. This is already more than just talk. Calpine officials said this week that the company has sunk "hundreds of thousands of dollars" on preliminary studies. By early next year the company will decide whether to take the next step and fund a feasibility study that would cost on the order of $100,000; according to spokesman Ken Abreu, the study would "look at threshhold issues from the county's perspective." What that means exactly is not yet clear. (One assumes the study would also look at the economic viability of the project for the company.) But one thing is coming into sharp focus: Unless Calpine backs out, a community notorious for its polarization over logging and other issues is going to have to make up its mind about whether it wants what Calpine is offering.

The tankers, 900 feet long

by 150 feet wide, would be the largest ships ever to enter Humboldt

Bay. Top photo: Calpine presentation Risky business The key issue will be safety. And when it comes to the safety hazard posed by LNG, there are two leading experts: Havens, who developed the computer software used by the federal government to determine the extent of safety buffer zones around facilities that handle LNG and other hazardous materials; and James Fay of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, who came to the nation's attention when he appeared on a 60 Minutes broadcast in the late `70s that examined the public safety hazard posed by LNG.

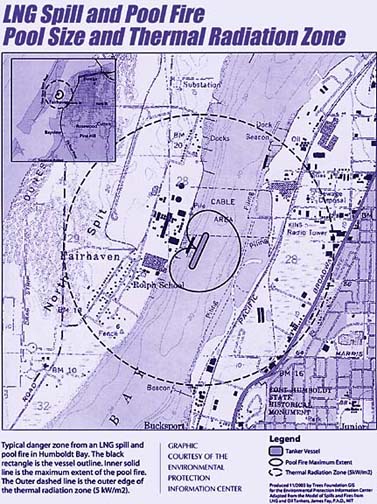

Fay was not reached for this story. But he recently authored a scientific paper that addressed what would happen in the event of an LNG tanker spill in Boston Harbor, which sees regular deliveries of LNG. The scenario he painted is, in a word, alarming. So are the scenarios described by Havens in his Bulletin article. But before getting to all that, it's first necessary to understand something about LNG itself. LNG is simply natural gas made so cold that it has condensed into a liquid. Why convert it? Because in its liquid form it takes up 600 times less space than it does when it's a gas. Chilling it, in other words, makes it possible to transport vast amounts of natural gas at an affordable cost. The downside is that concentrating natural gas in this way greatly increases its danger. It makes possible the ignition of an enormous amount of gas in one spot. Should LNG, usually at least 90 percent methane, be spilled directly into the environment, whether land or water, it will immediately begin to warm up and revaporize. Should the burgeoning gas cloud come in contact with an ignition source, such as a spark from a tanker's engine, it could catch fire and release a huge amount of energy in a matter of minutes. "Fires that burn thousands of tons of fuel in a few minutes are extraordinarily large, lying well outside the range of domestic firefighting experience," Fay wrote in his paper. "Such fires cannot be extinguished. The thermal radiation from such huge fires can be damaging to people and can set afire combustible buildings." Havens, in his Bulletin article, identified four different types of LNG "disaster scenarios," including "flammable vapor clouds" that could build up and drift directly over populated areas before igniting. While Havens said the formation of such clouds is possible, he said that most analysts discount the risk. "Most experts believe that an accidental release of an entire LNG ship storage tank, such as might occur in a collision, would result in the immediate ignition of the released gas. This would prevent the development of extremely large, and potentially more catastrophic, vapor cloud fires." Methane cloud explosions, while theoretically possible, are also considered unlikely, according to Havens. Of most concern, both Havens and Fay agree, is if large quantities of LNG were spilled onto water after, say, a tanker has been rammed by a terrorist boat loaded with explosives. Such a spill, as Fay explained in his paper, would be uncontainable. "Liquid fuels are lighter than sea water. They float, unmixed, on its surface. Most importantly, they speedily spread sideways, exposing the fuel to the air above. Once ignited, as is very likely when the spill is initiated by a chemical explosion, the floating pool will burn vigorously." Fay, at the end of that statement, was referring to an oil spill. An LNG pool fire would be different in that it is the gas cloud hovering directly above the spill -- which in its pre-ignition phase would look somewhat like a fog bank -- that burns, not the LNG itself. The size of an LNG pool fire would depend, of course, on how much fuel was released. But experimental spills of about 10,000 gallons of LNG performed in the 1970s and 1980s suggest that LNG pool fires could be massive. According to Havens, the tests produced fireballs 50 feet wide and 250 feet high. No one knows what sort of fire would ensue if the contents of an entire 6.5-million-gallon storage compartment on a tanker were to spill out because of a rupture. But predictions have been made. Fay has estimated that such a fire could be as much as a half-mile in diameter; Havens said at least a quarter-mile wide and likely larger. They didn't indicate the height of the flames, but based on the test spills it's safe to say hundreds of feet high, if not thousands. Even more apocalyptic, a 6.5-million gallon pool fire could engulf the entire tanker. What might happen in that event has never been studied. "Most predictions suggest that even the largest LNG tankers might be completely enveloped," Havens wrote in the Bulletin article. "This raises questions about the vulnerability of the ship and the potential for additional releases," he added. On the telephone this week, Havens said it would be incorrect to assume that, were all the storage tanks to fail and release the entire 33-million-gallon cargo, the resultant pool fire would be five to six times larger than the fire produced by a single-tank failure. But, clearly, it would be significantly larger. "It's hard to not feel like Chicken Little" when talking about possible LNG disasters, commented Cynthia Elkins, executive director of the Garberville-based Environmental Protection Information Center and an adamant opponent of the Calpine project. "But it's actually that catastrophic. The risks are low, but they do exist." Heat blast Havens makes clear that the risks of such a catastrophe are small; he calls an LNG pool fire, for example, a "low probability, high consequence" event. But the fact is Calpine will have to analyze pool fires and other worst-case scenarios if it goes forward with its Humboldt Bay project -- and it will have to prove to federal and state regulators, as well as to local officials and the public, that the risks are small enough to be acceptable. Since a detailed LNG risk analysis has never been done for Humboldt Bay, the best guide for what might happen in the event of a pool fire is Fay's study of Boston Harbor, which is similar in the sense that it features a relatively narrow shipping channel in close proximity to a populated area. If a single on-board storage tank were to rupture and empty all or much of its contents, and the floating LNG were to ignite, the "thermal radiation damage zone" would extend out nearly a mile in all directions, according to Fay -- and that's from the fire's outer edges, not from its heart. Within this zone of searing heat, people could be burned or killed and buildings could ignite. Assuming, in the case of the Calpine proposal, that such a fire were to begin near the most likely site for an LNG terminal dock -- bayside of the Simpson pulp mill site -- a significant slice of Eureka, not to mention the Samoa Peninsula community of Fairhaven, would fall inside the danger area. The mainland shore is a mere 2,000 feet from the proposed dock site, Bayshore Mall is less than half a mile away and Costco isn't much further -- nor is Highway 101. (See map.) If an expert analysis tailored to this area is done, it could lead to a different assessment, of course. But Havens was unequivocal in saying that, at a minimum, LNG terminals should be located two to three miles away from populated areas. He also called for federal safety regulations to take into account LNG spills on water; presently, they only pertain to land spills, which are comparatively easy to contain. Gven what Havens and Fay have written about LNG pool fires, it's clear that they are a danger to be taken seriously. So far, Calpine officials have not done that, at least not publicly.

Ken Abreu [on left in photo at left] , Calpine's director of market policy, was directly asked about the pool fire danger on Monday during a break in a panel discussion on the Calpine project sponsored by the Humboldt Bay Stewards. His response? "For sure, the other side of the bay [from the Simpson pulp mill site] would be in a situation where heat is not an issue." Perhaps Abreu was talking about an extremely small and confined pool fire. Otherwise, given Havens' and Fay's work, his statement appears to be false. Calpine project manager Kent Morton told the Times-Standard in August that any fire would be contained to the 80-acre pulp mill property. Havens said that would only make sense in the event of a land spill, such as from an LNG storage tank into a protective dike. "I don't know any basis for such a statement except if [the spill] were into a diked area and therefore contained," Havens said. Good safety record According to a recent report by the Congressional Research Service, the LNG industry has an impressive safety record stretching back 40 years. Since international LNG commerce began in 1959, "tankers have carried over 33,000 LNG shipments without a serious accident at sea or in port." The report added that, based on insurance records and industry sources, there have been 30 LNG tanker "incidents" -- leaks, groundings or collisions. Of these, "12 involved small LNG spills which caused some freezing damage but did not ignite," the report said. "Two incidents caused small vapor vent fires which were quickly extinguished." The report attributed the favorable safety record to the robust design of LNG tankers, which are double hulled. "LNG carriers are less prone to accidental spills than typical crude oil, fuel and chemical tankers," the report said. Land-based LNG facilities have also been relatively free of serious mishaps -- with one dramatic exception. In 1944, 2 million gallons of LNG escaped from a defective storage tank and spilled into the streets, and ultimately into the sewer system, in Cleveland. A ferocious fire ensued that killed 128 people. To an extent, the disaster has given the LNG industry a bad rep it doesn't deserve. The reason the tank failed was that it didn't include enough nickel alloy; it was wartime, and that metal was in short supply. Nonetheless, the taint is there to this day -- in no small part because of the 60 Minutes broadcast, which prominently featured the Cleveland tragedy. Safety record aside, there's no getting around the fact that LNG is inherently dangerous. Add in the terrorism concern that has arisen since 9/11, and it makes perfect sense that every LNG tanker that enters Boston Harbor has an armed Coast Guard escort. Similar precautions would undoubtedly have to be taken in Humboldt Bay, which is just one more reason the Calpine proposal has given some in the community pause. Tough meeting Other reservations were expressed at the recent panel discussion. Mark Hemphill-Haley, a geology professor at Humboldt State University, accused the company of understating the earthquake risk. Referring to the Samoa Peninsula, he also said that Calpine "couldn't have chosen a worse site" in terms of the tsunami hazard. Calpine, represented by Abreu, Robertson and Kirk Marckwald, a consultant, countered by emphasizing economics. Hundreds of jobs would be created during the construction stage, with a total of 50 to 60 permanent jobs while the terminal is in operation. Perhaps more important, the terminal would provide the county with millions in property tax revenues -- a true enticement at a time when the state budget deficit is creating major financial problems locally. David Narum, an HSU environmental engineering professor, expressed an economic reservation: that the heavy industry represented by the LNG terminal could harm property values. The Calpine trio stressed a couple of other things -- that the project was consistent with the coastal/industrial zoning at the pulp mill site (as well as an additional site under consideration, the Eureka Municipal Airport, which is not terribly far from the Simpson property); and that it was in accord with the harbor district's "revitalization plan," which identified four potential LNG terminal sites on the bay. Tom Hofweber of the Humboldt County Planning Department suggested that in other ways the project was not consistent with the county's vision of the bay's future. He pointed out, for example, that the county's general plan directs that terminals handling hazardous liquids like LNG be located off-shore, "unless it can be shown that it's environmentally preferable to put them inside the bay." Hofweber also pointed to something else that could potentially prove to be Calpine's Achilles' heel: A 1978 Coastal Commission siting study that rejected Humboldt Bay as a location for an LNG terminal. Why? Because putting one there would have violated a state law -- a law no longer in effect -- that banned the siting of LNG facilities near population centers. Divisions ahead?

Tina Christensen [photo at left] , in the real estate business like Lindstrom, has a different take on the matter. Standing in her bayside home just north of the Simpson site, she said in effect that Humboldt can't afford to be choosy. "I think Humboldt County needs more economic development. Should Calpine come in, they will replace some of the logging jobs that we've lost." So there you have it, a microcosm of Humboldt County's overriding reality -- polarization. Time will tell what that means for the Calpine project. Victory in Vallejoby KEITH EASTHOUSE At a press conference on May

3 of last year, elected officials of the city of Vallejo, standing

next to representatives of Bechtel, the construction giant, and

Shell Oil, and surrounded by business and labor leaders, announced

a bold new project that promised to be an economic shot in the

arm to the Bay Area community: the construction of a liquefied

natural gas terminal on a parcel of city-owned land on the southern

tip of Mare Island, a former docking site for nuclear submarines. [At right: LNG storage tanks superimposed on Mare Island] Four days later the Vallejo City Council unanimously voted to enter into an exclusive right to negotiate with Bechtel and Shell. By the end of the month, Bechtel and Shell revealed at a public meeting that they would fund a feasibility study that would examine the pros and cons of the project from the community's perspective. A vote on whether to approve that was scheduled to come before the council a few months later, in August. But between the end of May and the beginning of August, a sea-change of sorts came over Vallejo, long a gritty, blue-collar industrial town. People who had recently moved there, many to escape San Francisco's outrageous housing prices, were dismayed at the prospect of an LNG terminal in their backyard. So were some more established residents, who didn't want to see Vallejo return to its industrial past. Part of the displeasure stemmed from worries about the fire danger such a facility would pose. But people were also angry because the council was backing off from a prior commitment to turn the southern tip of Mare Island, which offers 360-degree views of the bay, into a regional park. "The community felt betrayed," said one of the newcomers, Stephanie Gomes. "The council maintained that nothing was written in stone, but in fact [the LNG] project was a complete U-turn. Vallejo had been known as the armpit of the Bay Area for a long time. This was a turn back toward that." Gomes, a U.S. Forest Service employee, along with Elena Ducharme, a Vallejo resident who works on the UC Berkeley campus, decided to fight. They started off by searching the Internet and discovering a wealth of information, some of it alarming, about LNG and the LNG industry. They started a signature-gathering drive against the project. They worked the media. They lobbied the council. They set up a booth at the local farmers' market. They distributed signs with a red slash through the words "LNG Gas Plant." In short, they did everything they could think of, and by the time the August meeting rolled around, they were having an impact, a big impact. About 600 people showed up, 90 percent of whom spoke against the project during a four-hour public hearing. Council members, clearly taken aback, shelved the feasibility study and opted for a different approach. They commissioned a $250,000 independent health and safety assessment, also to be funded by Bechtel and Shell. It was a watershed meeting in a number of ways, not least because the business and labor interests that had long dominated the town found themselves in the unfamiliar position of being in the minority. They came out "swinging," as Gomes put it, and launched their own grassroots effort -- which included the printing of T-shirts bearing the slogan, "Facts, not fear." "They tried to portray us as being fear-mongers," Gomes said. The battle culminated in January, when the council was presented with the signatures of 12,000 people opposed to the project. By this time the health study had been completed, and while its results were somewhat equivocal, the mayor, who had been the leading backer of the LNG project, seized on it as an excuse to turn against the deal. Shell then backed out, with Bechtel following in a couple of weeks. Why was the opposition so successful? According to Gomes, it was primarily because Bechtel and Shell misread the community. Vallejo was gentrifying, and the companies didn't take that into sufficient account. "We weren't the community they thought we were," Gomes said. Comments? © Copyright 2003, North Coast Journal, Inc. |

![[photo of Dick Lindstrom standing on pavement with old pulp mill in background]](cover1106-lindstrom.jpg)

![[photo of Simpson Site bayshore showing proposed location of LNG tanker at berth, storage tanks and power plant]](cover1106-powerpoint.jpg)

![[photo of LNG tanker]](cover1106-tanker.jpg)

![[photo of video of explosion]](cover1106-fireball2.jpg)

![[photo of video of explosion]](cover1106-fireball1.jpg)

![[photo of Ken Abreu and Kent Robertson of Calpine]](cover1106-calpineguys.jpg) When asked whether it wasn't too dangerous to locate

an LNG terminal near a populated area, Calpine spokesman Kent

Robertson [on right in

photo at left] was dismissive.

"It's an unfair criticism," Robertson said, speaking

by telephone from his San Jose office last week. "You could

play the what-if game with any and all proposals that come down

the pike. The timber industry could turn that around and say,

`What if a horrendous forest fire got started? Shouldn't we address

the problem by clearcutting the forest?' It's just too general

of a criticism to be addressed."

When asked whether it wasn't too dangerous to locate

an LNG terminal near a populated area, Calpine spokesman Kent

Robertson [on right in

photo at left] was dismissive.

"It's an unfair criticism," Robertson said, speaking

by telephone from his San Jose office last week. "You could

play the what-if game with any and all proposals that come down

the pike. The timber industry could turn that around and say,

`What if a horrendous forest fire got started? Shouldn't we address

the problem by clearcutting the forest?' It's just too general

of a criticism to be addressed."

![[Tina Christensen in her home]](cover1106-christensen.jpg) One

would think that folks living out on the Samoa Peninsula would

be united in their opposition -- particularly those in Fairhaven,

for whom the Calpine facility would literally be in their backyard.

And, according to Dick Lindstrom, a 68-year-old real estate broker

who's lived on the peninsula virtually his entire life, most

folks in Fairhaven, a community of 50 to 60 people, are against

it. "I've talked to quite a few locals and they tell me

they don't want it," Lindstrom said last week. Lindstrom

knows he doesn't want it. "We need to create jobs locally,

but I don't think [this project] is it."

One

would think that folks living out on the Samoa Peninsula would

be united in their opposition -- particularly those in Fairhaven,

for whom the Calpine facility would literally be in their backyard.

And, according to Dick Lindstrom, a 68-year-old real estate broker

who's lived on the peninsula virtually his entire life, most

folks in Fairhaven, a community of 50 to 60 people, are against

it. "I've talked to quite a few locals and they tell me

they don't want it," Lindstrom said last week. Lindstrom

knows he doesn't want it. "We need to create jobs locally,

but I don't think [this project] is it."![[Photo of Mare Island with tanks superimposed over view]](cover1106-MareIsland.jpg)