|

by BOB DORAN ON A WINDOW OF THE GENERAL STORE in Petrolia there's a bumper sticker bearing someone's idea of a town motto: "Shift happens." It's a pun and a double entendre. This is prime earthquake country -- the Mendocino triple junction, a convergence of faults, lies just offshore. It's also a place where people talk of a shifting paradigm, in particular a shift in the way humans relate to their environment.

Operating out of their vine-covered, rustic barn overlooking the mouth of the Mattole River, Simpson and Lapiner have been helping to shift the paradigm in the Petrolia area and beyond with their unique productions. "Human Nature has been a part of Humboldt County's cultural landscape for a long time, doing work totally unlike anybody else here," said Joan Schirle, artistic director of the Dell'Arte International School of Physical Theatre in Blue Lake. While Schirle said that the troupe's location out in Mattole country "means they're not on the radar screen as much as a [performing] group based in Arcata or Eureka," she noted that Human Nature's penchant for performing across the country and even abroad has gained it a reputation that extends far beyond Humboldt. The key to Simpson and Lapiner's success may be their scrappiness. "They have pushed this work out into the world as broadly as they can," Schirle said, "largely at their own initiative, finding sponsorships, finding people who are willing to present it." It hasn't hurt that on occasion they have received backing from a major donor, such as the prestigious National Endowment for the Arts.

It is reasonable to wonder, both with this show and with past Human Nature productions, whether the company isn't merely preaching to the choir, performing before largely liberal audiences that are predisposed to agree with whatever the status-quo-challenging message is. While there's no doubt some truth in that, the fact is Human Nature has been known to throw barbs in a leftward direction -- a mid-'90s show that had to do with the reintroduction of wolves to Yellowstone, for example, took issue with mainstream environmentalism's tendency to see people and nature as separate. And it's not completely clear that their audiences are as left as some might think. Simpson, who writes the plays, said that during the most recent national tour, "We performed for diverse audiences, liberal, conservative, knowledgeable about climate change and largely uninformed. Some cheered our biting satires; some were made uncomfortable by it." The global warming production was recently presented at the Mateel Community Center in Southern Humboldt and at Stanford University in the Bay Area. Northern Humboldt theatergoers can see it this weekend at Dell'Arte's Carlo Theatre. How did these not-so-young-anymore hippies -- both are 63 -- end up creating a theater company that for 20 years now has seen itself as an agent of social change? And what could be funny about climate change, anyway? Meeting The Human Nature story is long and winding, particularly when consummate storytellers like Simpson and Lapiner tell it. "Where to begin?" Simpson asked rhetorically in his Petrolia digs over a meal of wild salmon fillets and green beans fresh from the garden. The tale could start at one of several points in time, perhaps in the mid-'40s when Lapiner was a 5-year-old practicing ballet and modern dance in New York City, and Simpson was spending his boyhood fishing for walleyed pike in the Midwest. Instead, we begin in 1967, by which time both were living in San Francisco's Haight-Ashbury district. It was the fabled "Summer of Love" and -- in a nice bit of foreshadowing -- Simpson met Lapiner through his association with the fledgling San Francisco Mime Troupe, a theater company that produces politically sharp, satirical musical comedies. "I was an actor," Simpson recalled. "I was in a show called A Minstrel Show or Civil Rights in a Cracker Barrel, a great piece of theater on social issues. Jane was a dancer and choreographer, all the actors had to take her [dance] class. We met at a party and it went from there; I had a competition with a friend, a poet, to see who could make Jane laugh." "David won," Lapiner said with a chuckle. "I was the prize. How sexist can you get?" Feeling hemmed in by the urban scene, the new couple soon left the Bay Area and headed north in search of quieter surroundings. "From the time when we first got together we were `back-to-the-landers,'" Simpson explained. "We wanted to find a place in the country to raise a family. We wanted to be part of a rural community, to relate directly to the natural world, to figure out how to take our livelihood from it." Seeing For a while they lived on a ranch in Marin County that the actor Peter Coyote had rented. But they eventually ended up in a much more remote place, in a cabin in southern Humboldt County near the headwaters of the Mattole River. "We saw salmon spawning up there for the first time ever. We got a sense of the relationship of salmon to fresh water and its land base," Simpson recalled. After a time they moved to the opposite end of the watershed, near the mouth of the Mattole at a place called the Mathews Ranch. In 1974 they bought a portion of the ranch -- 50 acres -- at $450 an acre, a price that the locals considered outrageous since the land was seen as good for nothing more than grazing sheep. To Simpson and Lapiner, it was simply a beautiful place to live. It was also near a community -- Petrolia -- that had a school. "We had three kids at the time -- a fourth [Joyful] came in 1978 -- and we arrived with $35 in our pockets, a house truck and a borrowed school bus," Simpson remembered. "So, how do you make a living in a place like this? This was long before the traditional backwoods Humboldt livelihood emerged in the form of marijuana. That wasn't a factor. I was working as a $3-an-hour ranch hand and doing occasional carpentry for years, and it was a struggle." He also learned a lot more about the salmon that migrated up the river. It wasn't hard to see that the fish were in trouble. Droughts in the mid-'70s often left them trapped in pools along the Mattole, easy prey to poachers. "By the late '70s, everybody was aware that the salmon numbers were a pittance of what they had been, especially the ranchers. In fact, some of the first impulse for the initiative [to restore the watershed] came from the old-timers," Simpson said. One thing the ranchers were not ready to deal with was the impact logging had had on the salmon population. Most of the valley had been logged by the '70s, including the Mathews Ranch. The former owner, Wally Mathews, did his own logging. "People who worked for him said he was hard on the land, hard on the country. There are still a lot of scars to prove it," Simpson said. Battling It was the same for much of the valley. Unregulated logging had left streams clogged with debris and creek beds that were once prime spawning grounds buried in silt. In 1980 Simpson and a crew of like-minded salmon fans started "The Hatchbox Program," building micro-hatcheries along the Mattole where salmon were reared from eggs. "The restoration effort started with that," Simpson said. Over time the program would evolve into the Mattole Salmon Group and the Mattole Restoration Council. (See Journal cover story March 2, 2000: "If you rebuild it") The logging issue heated up in 1986 when a company called Collins Pine put 1,200 acres of unlogged timberland in the Upper Mattole up for sale. There was a brief move in the community toward purchasing the land to preserve it -- Rondal Snodgrass led the effort and eventually established Sanctuary Forest to buy most of the land -- but first Eel River Sawmills and Barnum Timber acquired the land and made plans for a timber harvest. "First thing they did was prepare to clear-cut on 200 acres at the headwaters, land that was the prime [salmon] spawning and rearing habitat," Simpson said. "Rondal and the upriver people asked us to get involved and we actually filed a lawsuit against Eel River Sawmills. They couldn't because they were involved in negotiations [to purchase the land]." Snodgrass also asked the Salmon Group to come upriver to join a protest against the timber harvest. Television crews were there, and what had been a conflict between local interests and a lumber company suddenly became "Timber Wars," as the Sacramento Bee put it in a headline. The community was polarized. "There was a lot of anger," Simpson recalled.

Left: David Simpson and Jane Lapiner on stage. Right: From left, actors Jane Lapiner, Joyful and David Simpson.

From left: puppet held by David

Simpson (Numero Uno), Joyful Simpson (The Raven) Resuming So what does all of this have to do with theater? The answer lies with Lapiner, who for several years after coming to Humboldt had time for little else besides her children. "After about three years I realized I hadn't taught a dance class or done any choreography. I went and rented the old Fireman's Hall in Garberville [which became the first Mateel Community Center] and started teaching dance classes. A group started to develop that would later become the Feet First Dancers. Then I choreographed a piece called Human Nature. It was kind of an opus; it took me several years to choreograph it one piece at a time."

Dancers were accompanied by live musicians and costumed in animal skins, feathers and bones. "The people I used ranged from slightly trained dancers to well-trained dancers," Lapiner said. "One year we toured with some high school kids I taught at Petrolia School. That piece was the basis for us to get back to the stage." She also choreographed other works for Feet First and for the high school, eventually establishing Human Nature as a nonprofit. In a slight shift, a piece about money called Oppression incorporated poetry and dialogue along with dance. Merging Meanwhile, Simpson was on the river trapping salmon as part of the restoration effort. But his theatrical past hadn't disappeared. "While they were on the traps they used to make up songs, about the hard work, about the salmon," Lapiner said. Among the early fish-trap songs was one called "My Girlfriend Is a Fisheries Biologist." It became part of Human Nature's first musical comedy, Queen Salmon. "We had the Alabama-Pacific forester singing that song," Simpson recalled. "He was in love with the Fish and Game biologist, but she would have nothing to do with him until he started seeing things the right way." The play debuted in 1991, a time when community conflict was at its height in the Mattole. "People were at each other's throats," as Simpson put it. "We had just endured Redwood Summer; Fish and Game was pushing for a zero-net-sediment discharge. California Department of Forestry coordinated a couple of public meetings. One at the Turf Room in Ferndale drew about 250 people, most of them just there to vent anger -- about regulation, about government, about environmentalists. It was really nasty; it nearly turned violent." "It was all more food for Queen Salmon," Lapiner pointed out. Simpson finished her thought: "We were creating this show about a community in conflict, between the logging and ranching elements and the newcomer environmental restorationists. It showed how a mutual love of salmon brought the community together." The play's satirical barbs poked fun at both sides; the intent was to get people to laugh at themselves, and through laughter to defuse tension. They took the show on the road with performances at HSU's Van Duzer Theatre; even the PL executives enjoyed it. The question was, did it change anything? "We like to think it played some role, large or small," Simpson said. After a number of people in the valley had seen the play, a meeting was held at the Mattole Grange. "It was like night and day," Simpson related. "I think people were so appalled by how bad things had gotten that they were ready to sit down and talk to each other." Growing The show would eventually have three tours up and down the coast with fine-tuning along the way. Schirle marveled at the community effort that went into the traveling productions. "The shows were almost tribal experiences," she said. "It was like they had half the population of Petrolia moving, taking the show on the road. Here you had a group of people connected because they shared the same watershed producing a cultural event. That's not done a lot." Inspired by the Queen Salmon experience, Lapiner and Simpson decided to take Human Nature to another level. With their next show, The Wolf at the Door, they paid salaries to company members. "We went heavily into debt," Lapiner said, laughing. "We discovered credit cards," Simpson added.

Stripped down, the piece was turned into a three-person show, Lapiner, Simpson and a singer/pianist. "We toured that show widely for several years," said Lapiner. Booking the show anywhere that would have them, Human Nature played everything from college campuses and environmental conferences to major theaters. Then came another shift. "In 1997 we were doing the show at this conference on sustainability in Istanbul, Turkey," Simpson said. "That was where we met the Inuit people. And we latched onto global warming as the critical issue to deal with." They learned that the Inuits, native people who live in Canada's Northwest Territory, have two great fears: One is interference in their way of life, particularly from environmentalists, the other is global warming. "We were intrigued," said Simpson. For years they had been following the old bumper sticker adage, "Think Globally, Act Locally." After having done the latter for years, the time seemed right to act globally. They decided to do a theater piece on climate change. Researching The initial concept was "Global Warming: The Musical." Simpson admitted that "getting people to take the idea seriously" was a hard sell. But with financial assistance from the Conservation and Development Forum (C&DF), a partnership between the Ford Foundation and the University of Florida, they traveled to the McKenzie River delta in the Arctic in 2000 to do research. "We found, of course, that the manifestations of climate change have proceeded apace there," Simpson said. "There's a saying among climate scientists that one degree of [temperature] change at the equator means three degrees change at the poles." Among the changes: melting permafrost, bluffs that used to be frozen solid sliding into rivers; walleyed pike, which Simpson was familiar with from his youth, appearing in the waterways; and grizzly bears showing up in polar bear territory, hundreds of miles north of their normal range. "That's the image we use to begin What's Funny About Global Warming?" Simpson said. "At the start of the story, a young Inuit man discovers a grizzly out on the ice and tries to grab him. He tells his father; his father doesn't believe him, saying the brown bears have never been there before, only white bears." Lapiner said that the Inuit people have mixed feelings about global warming. "There's ambiguity. They see the changes. Some they don't mind. It's getting a little bit warmer in the winter. And they are not willing to admit that it's the oil that is a big culprit in all of this. Oil makes their lives easier." Aside from providing employment, oil provides something else perhaps even more important -- fuel for snowmobiles, which make hunting infinitely easier. It's not surprising, then, that most Inuit people support the Bush administration's push for drilling in Alaska. ("But not all of them," Lapiner insisted.)

Staging Returning to the Mattole Valley with a renewed purpose, Lapiner and Simpson found themselves short on the funds required for the full-scale musical they had envisioned. Again they wrote for a "stripped down" troupe, this time just Lapiner, Simpson and Joyful. They began with short sketches performed on a local radio program. "Eventually we decided we needed to get out there and start proselytizing," Lapiner said. "We had a basic concept: The storyline of the show was going to be a narrative by the Raven. The Raven is a trickster, creator, and shape-shifter from many Northwest Coast native mythologies. We have the Raven enlisted by all the other animals to come among human beings and convince them that they have to change, convince them of the seriousness of what's going on." As the story progresses, Raven, played by Joyful, shifts into the form of a Marlene Dietrich-style chanteuse and a borscht-belt comedian; she spouts a Shakespearian-style soliloquy, does a belly dance. Lapiner and Simpson portray her raven assistants, who also take human form in a series of vignettes where they become, among other things, a scientist who is a paid greenhouse skeptic, a New Age thinker, a Mafia-style environmental enforcer, a Washington bureaucrat and the president of the United States. Last winter the family troupe took the show cross-country. Simpson pointed out with a touch of irony, "We drove 15,000 miles in the name of greenhouse gas emissions reduction." Or, as the Raven puts it at one point, they "committed the sin of ignition." With this show in particular some have raised the preaching-to-the-choir rap -- or as Lapiner prefers to put it, "reinspiring the choir." But she and Simpson are adamant that the global warming issue is different. "Even the so-called choir -- people who care about the degradation of the earth and want to do right by the environment -- they don't know the cold hard facts about climate change, and how extremely urgent it is," Lapiner said passionately. "Once they see the show, people really want to know what they can do about it. That's when we know we've done our part." Editor Keith Easthouse contributed to this report.

The ART of PERSUASION

"In my opinion climate change is the mother of all ecological issues," said Human Nature founder Jane Lapiner. "And it's happening so quickly. Scientists say that we have to rewire the planet in the next 15 to 40 years. That's the depressing fact. But, if we have the will to do it, it's possible." David Simpson, Lapiner's husband and the person who wrote the company's latest production, What's Funny About Climate Change? sounded a somewhat more downbeat note. He said a major obstacle to positive change is the Bush Administration -- in particular its rejection of the Kyoto Protocol, an international greenhouse gas reduction treaty. "The Bush administration and the oil industry are, shall we say, inseparable. And the oil industry wants to deal with [the problem] in its own time as it pleases. They know that a massive change is coming and we're going to have to go off the fossil fuel economy, but they're resisting it." "Anybody who is rational about this says the first thing that has to be done is to get rid of the Bush administration," Simpson went on. "I hate to say it, because it's simplistic. It's not the whole answer, but it's a start." It turns out that Human Nature itself is part of the answer, at least in the view of Dan Ihara, an economist who serves as executive director for the Arcata-based Center for Environmental Economic Development. He sees the theater company as an ally in the effort to convince the public that global warming is a major problem that must be addressed. "A lot of people get turned off when they hear climate change or global warming. [Through humor] Human Nature makes the whole subject fresh and accessible. In an entertaining way they make people realize the extent and urgency of the situation we face." Reported by staff writer Bob Doran and editor Keith Easthouse.

IN THE NEWS | ART BEAT | CALENDAR

Comments? © Copyright 2003, North Coast Journal, Inc. |

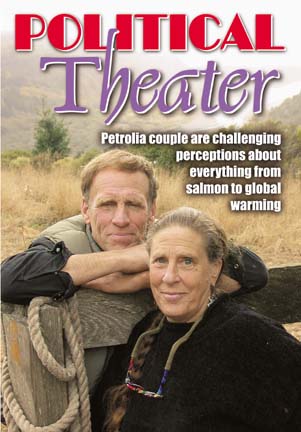

![[David Simpson sitting at table]](cover1023-davidsimpson.jpg) David Simpson, [photo

at left] an early leader in the

effort to restore salmon habitat in the Mattole watershed, has

long backed up such talk with action. So has his wife, Jane Lapiner

[photo below right] , whose involvement in political theater -- like

Simpson's -- goes back to the `60s. Together, they run Human

Nature, a cutting edge theater troupe known for its pro-environment

bent, its biting political satire and its zany musical comedy.

David Simpson, [photo

at left] an early leader in the

effort to restore salmon habitat in the Mattole watershed, has

long backed up such talk with action. So has his wife, Jane Lapiner

[photo below right] , whose involvement in political theater -- like

Simpson's -- goes back to the `60s. Together, they run Human

Nature, a cutting edge theater troupe known for its pro-environment

bent, its biting political satire and its zany musical comedy.![[Jane Lapiner sitting at table]](cover1023-janelapiner.jpg) Human

Nature's latest production, a three-person comedy called What's

Funny about Global Warming? takes on, as the title indicates,

the controversial issue of climate change. Performing in 24 U.S.

cities from February through April, mostly in front of college

and university audiences, the troupe (made up of Simpson, Lapiner

and their 25-year-old daughter, Joyful Simpson) has received

a series of enthusiastic reviews.

Human

Nature's latest production, a three-person comedy called What's

Funny about Global Warming? takes on, as the title indicates,

the controversial issue of climate change. Performing in 24 U.S.

cities from February through April, mostly in front of college

and university audiences, the troupe (made up of Simpson, Lapiner

and their 25-year-old daughter, Joyful Simpson) has received

a series of enthusiastic reviews.![[actors on stage]](cover1023-stage2.jpg)

![[actors on stage]](cover1023-actors.jpg)

![[actors and puppets on stage]](cover1023-stage1.jpg)

![[Human Nature logo with raven]](cover1023-humannature.gif) Part one, Deer People, premiered in 1979,

followed by Bobcat People, Bear People and Salmon/Raven

People. The sections were performed individually and together.

"It was a major intellectual effort to examine the spiritual

and cultural roots of the back-to-the-land movement," Simpson

explained.

Part one, Deer People, premiered in 1979,

followed by Bobcat People, Bear People and Salmon/Raven

People. The sections were performed individually and together.

"It was a major intellectual effort to examine the spiritual

and cultural roots of the back-to-the-land movement," Simpson

explained.![[artwork for "The Wolf at the Door" Musical comedy]](cover1023-wolf.gif) The play grew out of a piece Lapiner developed

with Petrolia High School students. "We were exploring ideas

about wolves being demonized, yet they had family values and

so forth. David helped expand on that to speak to the preservation

of wolves, but also addressing our human relationship to the

wild, coexistence with wildness."

The play grew out of a piece Lapiner developed

with Petrolia High School students. "We were exploring ideas

about wolves being demonized, yet they had family values and

so forth. David helped expand on that to speak to the preservation

of wolves, but also addressing our human relationship to the

wild, coexistence with wildness." That's one reason Inuits don't like environmentalists.

Another is the controversy surrounding seal hunting. When Greenpeace

led a campaign against clubbing baby harp seals, they called

for an international boycott on all seal pelts. It proved successful

and was a major blow to the Inuit way of life. "Welfare

dependence and alcoholism sprung up. It hurt them badly,"

Simpson said.

That's one reason Inuits don't like environmentalists.

Another is the controversy surrounding seal hunting. When Greenpeace

led a campaign against clubbing baby harp seals, they called

for an international boycott on all seal pelts. It proved successful

and was a major blow to the Inuit way of life. "Welfare

dependence and alcoholism sprung up. It hurt them badly,"

Simpson said.![[Bumper Sticker "Shift Happens - Petrolia, California"]](cover1023-shifthappens.jpg)

WHY DID A REGIONAL THEATER COMPANY

LIKE HUMAN NATURE tackle a global problem like climate change?

WHY DID A REGIONAL THEATER COMPANY

LIKE HUMAN NATURE tackle a global problem like climate change?