|

by KEITH EASTHOUSE THE NORTH FORK OF THE ELK RIVER LOOKS RELATIVELY harmless at this time of year, just a dark creek, really, full of tannins and orange algae with muddy banks and a muddy bottom. It's not pleasant to look at, and it's not a healthy environment for fish (they need gravel to nest in, not muck), but these days that's par for the course for North Coast waterways that flow down out of commercial timberlands owned by the Pacific Lumber Co. But frightening? How could this poor excuse for a river frighten anyone? Miklos Kallo knows how. And you would too if you'd been with him out at his place in the Elk River Valley two days after Christmas last year. It started raining in the morning -- hard. And it kept raining hard, hour after hour after hour -- until the all-time 24-hour rainfall record was set in Eureka. Until some people began to wonder if it would ever stop. Until Kallo saw the North Fork Elk like he'd never imagined it -- a giant brown foaming thing that looked exactly like a lake except it was all moving in one direction. Kallo didn't know it at the time, but the river was 22 feet above its bed, higher than during the epic 1964 flood. It was up almost to the top of the concrete guardrails of the bridge that's less than 100 feet from his modest cream-colored with green trim home on Wrigley Road. It was lapping at the edge of his front porch. It was within inches of spilling into his living room.

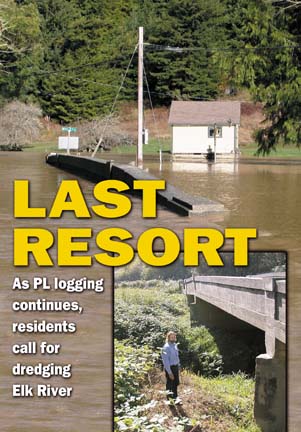

Late in the day, he and his 23-year-old son Benjamin -- who was home for the holidays -- were looking out at the bridge when they heard a "crunching sound." It was the wooden stairs and railing leading up to the porch beginning to tear away. That's when his wife, Paulette, got on the phone and requested emergency assistance. It took awhile, several hours, but around midnight a strange vision emerged out of the darkness. Two large men wearing headlamps were wading with painful slowness against the flood, towing a rubber raft that contained two other men, armed with oars and furiously paddling. They were all firemen, and they'd been forced into the drink after their fire engine could go no farther. It took them at least 20 minutes to go a few hundred feet, but eventually they reached a small deck at the back of Kallo's house that, bizarrely, was now serving as a dock. Two at a time, Kallo, Paulette, Benjamin and the family dog were taken by raft to the far end of their property, where there was a barn on higher ground. They huddled inside, made a bonfire and stayed there the rest of the night. It would take days for the flood to recede, but the worst was over. They, and their house, had survived. Photo above left: Miklos Kallo and his dog, Maggie, had to be rescued from record flooding on Dec. 27, 2002. Clogged artery Harrowing flood tales are hardly new in the Elk River Valley, a 31,400-acre watershed southeast of Eureka that has been beset by chronic flooding during winter storms for several years now. But the spate of major rain events during the latter half of December 2002 produced flooding and property damage that was out of the ordinary even by Elk River standards. That's a major reason why 56 Elk River residents signed a petition earlier this month requesting that the North Coast Regional Water Quality Control Board do something that has never been done before: dredge several miles worth of the Elk River, which has become so clogged by sediment and debris from upstream timberlands that it has lost much of its channel-carrying capacity. And the residents aren't simply talking about dredging the river a year or two from now, after a slew of permits have been obtained. As their four-page petition puts it, they want the water board to "authorize and direct the commencement of dredging within 30 days, but certainly before winter rains bring additional deposits of sediment or trigger more nuisance flooding." Not only that, they want the river dredged repeatedly to ensure that it doesn't simply fill back in. The petition comes hard on the heels of a meeting last month in which the seven-member board directed its staff to investigate the feasibility of dredging Elk River as a way to alleviate the flooding. "It is my feeling that those individuals need to have relief from the flooding that has occurred due to aggradation [sedimentation] of the streamway," board member Beverly Wasson, a Sonoma County grape grower, said in a telephone interview this week. The petition also comes at a time when the water board, long criticized for failing to rein in PL logging in the two basins, has just gained a new power. Thanks to legislation signed earlier this week by ousted Gov. Gray Davis, the board now has the final say over timber plans that pose an unacceptable threat to water quality. Whether the board will actually exercise that power remains to be seen. The call for dredging Elk River, which would likely require the use of excavators directly in the stream or on its banks, is causing some concern among environmentalists. "Dredging is such a destructive process that it's really an admission of the absolute failure of everything else," said Mark Lovelace of the Humboldt Watershed Council.

Above: a familiar site for residents -- the Elk River in flood over Berta Rd. Floods worsening? According to Jesse Noell of Salmon Forever, a watershed restoration group, several homes that had been flooded before were flooded again last December, including the home he was living in at the time, a red house not far from the Kallos, and not far from the confluence of the north and south forks of the Elk. It was the fifth time that it has been inundated over the past several years. But it's not the repeat flooding that Noell emphasizes when talking about last December. It's that homes that had been high enough to stay dry before also got overwhelmed. "Six or seven houses [in Elk and the Freshwater basin to the north] that hadn't been flooded before got flooded," Noell said. That may not sound like a huge number. But in Noell's mind it's very significant. The California Department of Forestry has restricted logging in both watersheds to levels aimed at ensuring that flooding conditions will not worsen. The cap is similar in the two watersheds, 500 clear-cut equivalent acres in Freshwater and 600 in Elk. (PL cannot clearcut any more land than that, though it can log more acreage if it uses lighter logging methods, such as selective harvesting.) Noell said the events of last December prove that flooding is worsening and that CDF's ceiling is too permissive.

The analysis for Freshwater, the first basin PL examined, is done, and according to Marshall the 500-acre limit is going to remain in place. That's bad news for the company, which had been hoping to see it raised. And it's bad news for Freshwater residents, who blame the flooding on excessive logging. The analysis for Elk is not yet complete, so it is not yet clear what will happen to the 600-acre limit in effect there. Logging frenzy There is no question that in the 1990s Pacific Lumber greatly accelerated the rate at which it was pulling timber out of the Elk and Freshwater basins. Take the North Fork Elk sub-basin upstream of Kallo's house, not to mention the property of longtime resident Kristi Wrigley, whose apple orchard has been, she believes, severely damaged by repeated flooding in recent years. From 1974 to 1987, the company logged an average of 72 acres per year of the 14,600-acre sub-basin. Over the next 10 years, from 1987 to 1997, the rate of logging jumped sevenfold -- to 504 acres per year. The increased cut produced a host of violations of state logging regulations -- from 1990 to 1997, CDF issued 64 violation notices to the company regarding its logging operations in the North Fork. The cutting binge unleashed massive amounts of sediment into the river. From 1994 to 1997, landslides in freshly cut areas of the watershed bled sediment into the North Fork at a rate 13 times greater than landslides in parts of the watershed that hadn't seen cutting in 15 years or more. The total amount of sediment deposited in the river during that period was a whopping 84,000 cubic yards -- 95 percent of which came from harvested areas and logging roads. While logging slowed after this period, it picked up a couple of years ago and there is plenty of evidence of ongoing damage. In places, sediment deposition in the Elk watershed is six to eight feet above the river's original gravel bed. Regional water board staff "observed significant channel, bank and floodplain aggradation" following the major storms of last December, and they estimate on the basis of an evaluation of watershed conditions that "flood severity" in 2001 was 135 percent worse than it was in 1997. Finally, a study this year of nine North Coast streams by local hydrologist Randy Klein found that the North Fork Elk River was clogged by sediment for longer periods of time than any of the other waterways. To be sure, Pacific Lumber has taken steps to restore the watershed, notably through an ongoing effort to rehabilitate logging roads, the single greatest source of sediment deposition over the long term. But that doesn't do much about what one of its own consultants, the Arcata-based Pacific Watersheds Associates, identified as the top source of sediment deposition today -- landslides, which account for more than half of the total volume of material delivered to stream channels in the basin. Both PL and CDF have repeatedly denied any linkage between recent cycles of logging and flooding in the Elk and Freshwater basins. In its "watershed analysis" of Freshwater, for example, the company acknowledged the presence of "high levels of fine sediment in many areas," but said the sediment is a product of natural erosion and of activities that occurred 40 to 135 years ago, "particularly related to (logging) road construction and use." It said the flooding that occurred in Freshwater in the mid-to-late 1990s was due to increased rainfall compared with the preceding 10- to 15-year period. Bill Trush, adjunct professor in the Fisheries Department at Humboldt State University, said, "I totally disagree" when asked to respond to the claim that so-called "legacy logging" was behind the present day flooding problems in Freshwater and Elk. He said the proof can be found in the middle reaches of the Elk River basin, up on Pacific Lumber land. Because the terrain there is steep and narrow, the waterways "don't store sediment"; instead, they flush material out quickly. Nonetheless, these reaches are still severely clogged by fine particles. Why? Because of erosion from fresh clearcuts. Another bit of evidence was offered by fisheries biologist Patrick Higgins. As late as the late 1980s, Higgins said, the Elk River was "the best coho fishery in the state." Today, coho salmon, a federal "threatened" species, are barely hanging on. Below right: Kallo indicating the height of the Dec. 27, 2002 flood. Tough sell

Trush said he couldn't "deny that dredging would provide short-term relief from flooding." But he said that coming in with heavy equipment such as excavators could damage fish habitat and aggravate bank erosion, particularly if heavy flooding happens afterwards. Cynthia Elkins, head of the Garberville-based Environmental Protection Information Center and usually a staunch ally of Elk River residents, said that dredging would be pointless if logging continues upstream. "If you dredge at this point [with logging continuing], it will just all fill back in. What we need to do is stop the input of sediment. That needs to be done immediately." Elkins raised another objection: that removing sediment from the Elk River system through dredging would serve as a convenient excuse for the water board to continue to do nothing about curbing the rate of logging. She said it would also hand Pacific Lumber a justification to continue its logging. "What better way for them to claim they can continue putting in sediment," Elkins said, adding that the company has frequently gone on record as favoring dredging. Whether that means the company would pay to dredge Elk River -- a job that would likely cost in the millions, is unclear. Jared Carter, who for a long time served as one of PL's attorneys, indicated at a water board meeting in Eureka in April of last year that the company would be willing to shoulder some of the burden. "I've personally talked with people in county, state and federal governments about the possibilities of putting together some kind of dredging effort. And we will continue to do that. And we'll stand ready to donate equipment, people -- spend some money -- if there's something that can be done that looks like it has any opportunity for success."

Which brings up what is perhaps the biggest sticking point -- permitting. Bertain said a "statutory exemption" in California's Environmental Quality Act obviates the need for regulatory approvals on dredging projects in emergency situations. Noell said such an exemption came into play when holding ponds were dredged above the town of Stafford after a debris torrent from PL timberlands buried the place on New Year's Day 1997. "If life and limb are at stake," the exemption applies, Bertain said. Even if that were the case and an agency such as the state Fish and Game Department were shut out from having authority over the project, the exemption would not apply at the federal level. David Ammerman, a wetlands biologist with the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers' regulatory branch in Eureka, said that at a minimum the corps would need to inspect the project. If the excavated material is to be disposed of in a wetlands, then the Corps would have to permit the project before it could go forward, Ammerman said. He also said that simply excavating in a streambed could trigger the Corps' permitting authority. And he said that if federally protected species are involved -- and they are in the form of coho and Chinook salmon and steelhead -- the Corps would need to consult with the National Marine Fisheries Service to determine possible impacts. Catherine Kuhlman, executive director of the water board staff, said that her people are still evaluating what regulatory bodies would need to approve the project. But she said she expected that if the water board decides to go ahead with dredging, it is likely to be a long and complicated process. Bottom line: Despite what Bertain's petition says, it's doubtful in the extreme that any dredging of the Elk River is going to take place before the rains come. No-brainer

Souza, who runs beef cattle on 10 acres in the Lower Elk, seemed upbeat the other day. But that seemed to have more to do with this 56-year-old's personality than with anything else. The fact is he can't pasture his cattle on the land year round like he used to because the grass the animals depend on gets covered in muck from winter floods. And he lost 600 feet of fence in the storm last December, which he had to pay to replace out of his own pocket. Which is about all you need to know to understand why Souza wants the Elk dug out. "I'm all for dredging the river, you bet," he said.

IN THE NEWS | GARDEN | GOOD NEWS | CALENDAR

Comments? © Copyright 2003, North Coast Journal, Inc. |

And

Kallo, a grizzled 63-year-old Vietnam vet who suffers from post-traumatic

stress syndrome, was coming this close to losing it.

And

Kallo, a grizzled 63-year-old Vietnam vet who suffers from post-traumatic

stress syndrome, was coming this close to losing it.

Whether flooding in

the two basins is indeed getting worse, and what role logging

in the upper reaches of the two basins is playing, is "the

$64,000 question," according to CDF Deputy Chief John Marshall.

Marshall said the matter is being addressed through the "watershed

analysis" process that Pacific Lumber is conducting under

the terms of its 50-year Habitat Conservation Plan, a set of

logging restrictions aimed at protecting endangered species that

PL agreed to operate under as part of the Headwaters deal. The

purpose of the analysis is to determine the appropriate scale

and type of logging for every watershed on Pacific Lumber's 211,000

acres. In other words, the restrictions PL is currently operating

under could change depending on the results of the watershed

studies.

Whether flooding in

the two basins is indeed getting worse, and what role logging

in the upper reaches of the two basins is playing, is "the

$64,000 question," according to CDF Deputy Chief John Marshall.

Marshall said the matter is being addressed through the "watershed

analysis" process that Pacific Lumber is conducting under

the terms of its 50-year Habitat Conservation Plan, a set of

logging restrictions aimed at protecting endangered species that

PL agreed to operate under as part of the Headwaters deal. The

purpose of the analysis is to determine the appropriate scale

and type of logging for every watershed on Pacific Lumber's 211,000

acres. In other words, the restrictions PL is currently operating

under could change depending on the results of the watershed

studies. Given

all this, and the fact that the Elk River for the past six years

has been listed as "sediment impaired" under the Clean

Water Act, it's little wonder that residents are calling for

dredging. But the idea is not going over well in some quarters.

Given

all this, and the fact that the Elk River for the past six years

has been listed as "sediment impaired" under the Clean

Water Act, it's little wonder that residents are calling for

dredging. But the idea is not going over well in some quarters. Bill

Bertain, the Eureka lawyer who filed the dredging petition for

the residents, is adamant that PL cover the entire cost. He said

dredging would have to be done very carefully, perhaps via buckets

and conveyor belts. But given the large amount of sediment that

he says needs to be removed, on the order of 100,000 cubic yards,

it would seem highly doubtful that the job can be done in the

timely manner Bertain says he wants it done in without heavy

equipment.

Bill

Bertain, the Eureka lawyer who filed the dredging petition for

the residents, is adamant that PL cover the entire cost. He said

dredging would have to be done very carefully, perhaps via buckets

and conveyor belts. But given the large amount of sediment that

he says needs to be removed, on the order of 100,000 cubic yards,

it would seem highly doubtful that the job can be done in the

timely manner Bertain says he wants it done in without heavy

equipment. That means that

residents like Kallo and Lucindo Souza [photo at left] could

be in for it again this winter.

That means that

residents like Kallo and Lucindo Souza [photo at left] could

be in for it again this winter.