Sept. 30, 2004

IN

THE NEWS

| GARDEN | THE HUM | CALENDAR

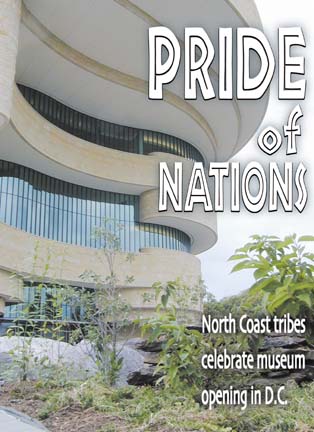

National Museum of the American

Indian in Washington D.C.

Photo by Judy Hodgson

Story & photos by JUDY HODGSONz

[Photo album at end of

story]

ABOUT 10 YEARS AGO MERV GEORGE

SR. WAS IN WASHINGTON, D.C., to testify before a congressional

committee on some issues. While he was there he decided to tour

the Smithsonian Natural History Museum's exhibit of the Hupa,

his own tribe. What he saw was a male mannequin standing with

a spear -- a weapon more appropriate for an African exhibit.

The female mannequin wearing a crude, matted horsehair wig and

a beaded dress that is normally used only for the tribe's sacred

dances was inexplicably grinding acorns, a kitchen chore. A young

child looking at the exhibit said to his mother, "Look Mommy,

she doesn't have clothes on" underneath the elaborately

beaded top of the dress. The mother replied that was how Indians

dressed in the old days -- long ago.

"I was embarrassed by it,"

George said earlier this month in an interview with the Journal.

He said he wanted to tell the Smithsonian visitors that the Hupa

are still very much alive -- that they still dance and sing and

practice their own religion. He wanted to tell them the Hupa

-- his people -- never fully stopped practicing their cultural

way of life despite decades of attempts at forced assimilation

by the U.S. government.

![[Group of Hupa, some in regalia]](cover0930-Hupa.jpg)

Front row left to right: Merv

George Sr., religious dance leader and keeper of the regalia

for the Hupa tribe; Laura Lee George; two of their 12 grandchildren,

Merv George III (behind) and Deja Rain George; and David Risling.

[Photo by Bob Hodgson]

George was silent and ashamed

that day in the old Smithsonian. But he was beaming with pride

last week as he, his family and other Hupa, Yurok, Tolowa, Wiyot

and Karuk from the North Coast, joined an estimated 25,000 other

Native Americans on the National Mall. With many in full regalia

-- and with great dignity and joy -- they walked toward the Capitol

that day to celebrate the opening of the newest Smithsonian:

the National Museum of the American Indian.

George [photo below left] ,

now 60, grew up on the Hoopa Reservation listening to stories.

(Hoopa is the land, Hupa are the people.) His mother told him

of the government-run boarding school she was forced to attend

as a girl when the reservation was occupied by federal troops

stationed there at Fort Gaston.

"It was a school they put

them in to teach them how to be a seamstress, leather worker,

[or] farmer," George said. "You weren't allowed to

speak your language. You weren't allowed to do your dances."

The federal government was not alone in its attempt

to "civilize" the Hupa. Christian churches sprang up

and, with the blessing of the government, competed for converts. The federal government was not alone in its attempt

to "civilize" the Hupa. Christian churches sprang up

and, with the blessing of the government, competed for converts.

"At one time there must

have been seven or eight churches in the valley," George

said. "They were trying to get younger people involved.

What I didn't like when I was growing up is ... they used to

march us over to the Presbyterian Church from the school and

set us down and preach to us for an hour -- tell us we're going

to die, we're going to burn in Hell if we didn't believe.

"Do you know what that

does to an 8-year-old psyche? I used to go home and ask my mother,

am I going to die if I don't believe in that, what they believe

in?"

The obvious conflict is that

the Hupa have always had their own spiritual beliefs.

"From day one I was taught

that you believe in the spirit people," George said. "The

spirit people [take] care of us. We talk to them, we pray to

them. Everything has a life -- everything. Even the trees dance."

The Hupa religion is one based

on balance, explained George, who is the religious dance leader

of the tribe and keeper of the regalia. If there is a war going

on somewhere in the world as there is now [some Hupa are serving

in Iraq], if someone is sick, the Hupa dance and pray.

"Our Jump Dance is designed

for that -- to try to drive evil things, bad things, away [and]

bring back balance again," George said. The Deerskin Dance

is done before the Hupa set out to gather things -- deer meat,

fish, acorns -- "so we can live our lives in balance."

Some Hupa did convert to Christianity

and remain Christian today, creating a conflict of beliefs in

the tribe. For a time when the dances were forbidden, some tribal

members danced and prayed in secret in the hills. George's grandmother

told him of the time the Hupa tribe formally petitioned the federal

government for permission to perform their sacred dances, and

it was granted on one condition.

"They had to walk under

this [American] flag hanging in the tree up in Bald Hill,"

where the dances would end up.

George said in 1954 the government

wanted to make a reservoir out of the Hoopa Valley by putting

a dam near Weitchpec.

"I was a young fellow then,"

he said. He recalls that it was the sacred dances performed on

land that the government wanted to flood that raised questions

of religious freedom and eventually saved the valley.

George worked for the city of

Eureka for 30 years before he retired as a maintenance supervisor

six years ago. He raised his family in the city but always called

Hoopa home. He also has been a professional musician since he

was 12. Occasionally his band, the Merv George Band, comes out

of retirement, with his 31-year-old son, Merv George Jr., on

drums. His music -- the country tunes, rock 'n' roll and funk

-- are all retained in his memory. So are his tribal prayers,

songs and chants. He said he can sometimes still hear the voice

of his grandfather, who was also a gifted singer, in the back

of his head.

"There is nothing written.

People used to put them down on tapes [but] some of the songs

are nothing more than just sounds," he said.

"When I was growing up,

my mother told me, don't bother the people over there. They're

putting on a dance," George said. So he used to sit and

listen to the elders sing, and he learned from them.

George received his family's

dance regalia from his great uncle through his uncle. He was

chosen to lead the religious dances.

"It's handed down through

generations. We have always done these dances, no matter what

they [the federal government] tried to do to us."

![[Front of National Museum of the American Indian building with trees andn rocks landscaping]](cover0930-IndianMuseum.jpg) Because

of his interest, knowledge and leadership position in the nearly

3,000-member tribe, George was recommended five years ago to

the Smithsonian as a consultant by David Risling, a retired professor

from UC-Davis and a tribal member. It was a great honor for the

Hupa because only 24 or the more than 400 tribes of the Americas

were chosen to have a major exhibit at the opening of the new

museum. Because

of his interest, knowledge and leadership position in the nearly

3,000-member tribe, George was recommended five years ago to

the Smithsonian as a consultant by David Risling, a retired professor

from UC-Davis and a tribal member. It was a great honor for the

Hupa because only 24 or the more than 400 tribes of the Americas

were chosen to have a major exhibit at the opening of the new

museum.

Museum officials came out to

Hoopa and asked if George would serve as a curator along with

his wife, Laura Lee George, assistant superintendent of the Klamath-Trinity

School District; his son, George Jr., a fisheries consultant;

and his daughter-in-law, Wendy George, a firefighter who serves

on the Hoopa Tribal Council. The four were flown back to Washington

to help identify artifacts and explain how they were used and

how they should be displayed. Some of the pieces were from the

original Smithsonian collection and many others were recently

donated as part of the collection of the late George Gustav Heye

of New York. Daughter Melodie George, a linguist who teaches

the Hupa language at Hoopa High School and Hoopa Elementary,

was also instrumental in the final design and content of the

new exhibit, as was Risling.

George Sr., in particular, was

excited about the project because of his experience a decade

ago. "[I thought] here's my way of trying to right the wrong

[of how] they depicted us back there."

In doing so, George chose a

path of cooperation with a government that unfairly treated his

people in the past. He even contributed a few modern items to

the current exhibit, including a ceremonial stick that holds

the museum's white deerskin. There are others in his tribe, he

said, who believe all artifacts possessed by the government and

private museums should be returned to the tribes, not just sacred

items and human remains. (See sidebar.)

The day dawned clear on Tuesday,

Sept. 21. Visitors arriving by the nearest Metro station two

blocks away emerged from the underground to see the sun rising

over the new $219 million museum, a tan edifice resembling the

windswept sand cliffs of the American Southwest. Approaching

from the rear along Maryland Avenue, the structure looks enormous

compared to the adjacent gleaming white Capitol dome.

In front of the museum entrance

on the Mall is a wetlands with a meandering stream and water

spilling over slabs of rock. Giant boulders, called grandfather

rocks, a sacred Native American symbol, dot the landscape, along

with native plants. Along one side is a vegetable garden of corn

and squash.

![[Side view of museum building and street]](cover0930-museum.jpg)

Early morning view on Maryland

Avenue.

A consulting firm created

a written architectural concept for the Smithsonian and its new

National Museum of the American Indian in 1991 that guided a

multi-year consultation process involving Native peoples. The

museum's architect and project designer is Douglas Cardinal (Blackfoot)

of Ottawa, Canada.

Groups of First Americans, the

term used during the opening week of celebration, representing

more than 400 tribes, began arriving shortly after daybreak.

Their regalia was sometimes more colorful, and certainly as varied,

as the birds of the world. From South America came one dignified

group in somber-tone handwoven plaid shirts buttoned up to the

neck. Turn another way and there was a proud warrior from Colombia

elaborately clad head to toe in peacock feathers, beads and gold.

Tribes gathered at the opposite

end of the Mall, past the Smithsonian Castle near the Washington

Monument. The plan was for each tribe to report to a color-and-number-coded

sign --3, for instance -- which were set up in neat rows. At

exactly 10 a.m. the tribes were to merge alphabetically into

two lines and proceed up the Mall to seats facing the stage in

front of the Capitol.

But the celebration began hours

early with impromptu performances of chanters, dancers and drummers,

groups posing for photographs and video cameras. Every once in

a while organizers would ask over a loudspeaker for one line

or another to move forward, closer toward the starting point.

Finally, about 20 minutes ahead of schedule, the procession surged

forward, with volunteers attempting in vain to keep the spectators

at bay. No one appeared to be the least bit upset about the festive

disorganization, except for a television news crew from MSNBC

who were jostled around.

![[inside building]](cover0930-insidemuseum.jpg) The

mood of the participants was triumphant. It was the largest gathering

of Native Americans ever, and those participating sensed the

historic significance. Somewhere along the route, tribes starting

with the letter "S" began appearing before those with

an "M" and nobody cared. The

mood of the participants was triumphant. It was the largest gathering

of Native Americans ever, and those participating sensed the

historic significance. Somewhere along the route, tribes starting

with the letter "S" began appearing before those with

an "M" and nobody cared.

Once settled in their seats,

the crowd listened to speeches by Sen. Daniel Inouye (D-Hawaii)

who, along with Sen. Ben Nighthorse Campbell (R-Colo.), sponsored

the 1989 legislation passed by Congress that mandated the museum's

construction. Inouye said it was nearly two decades ago that

he realized out of the 400 statues and monuments in D.C., there

was not one for the Native American -- a wrong that needed righting.

W. Richard West Jr., the museum's

director and a member of the Southern Cheyenne tribe, told the

gathering just prior to the ribbon cutting: "To those of

you within sight and sound of this occasion, and who descend

from those who came, welcome to Native America. And I say to

those of you who descend from the native ancestors, who are already

here, welcome home."

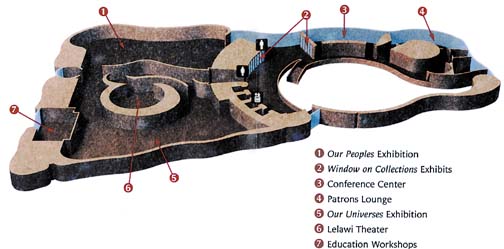

Due to crowds, estimated to

be about 80,000, only those with advanced tickets could actually

tour the museum that day. Inside visitors were greeted by a 120-foot-tall

glass-topped rotunda shaped like a perfect sphere and ringed

by balconies on each of the four levels. The first floor has

a main theater for stage plays, storytelling, dance and music

presentations. A cafe features cedar-planked salmon, nuts and

fresh berries, buffalo burgers and Indian frybread.

Approximately 8,000 objects

from the museum's permanent collection are on view throughout.

The Hupa exhibit, on the fourth floor, is part of three permanent

groupings called "Our Universes," "Our People"

and "Our Lives." These 24 inaugural exhibits will be

on display until at least 2006 when the museum will begin to

rotate exhibits from other tribes.

The George family and Risling

are featured in a photo gallery as curators near the entrance

to the Hupa exhibit. In the interview two weeks ago, George Sr.

said his son had previewed the final display last month and was

pleased, but he himself would be viewing it for the first time

at the opening.

![[inside museum, looking up at dome]](cover0930-dome.jpg) Just

past the entry, visitors step through a round opening made of

wood that resembles a cedar plank house. (George said the museum

staff originally wanted to reconstruct an entire building but

there wasn't enough room.) Inside behind glass are artifacts

and mannequins in dance regalia authentically depicting the Hupa

people. Just

past the entry, visitors step through a round opening made of

wood that resembles a cedar plank house. (George said the museum

staff originally wanted to reconstruct an entire building but

there wasn't enough room.) Inside behind glass are artifacts

and mannequins in dance regalia authentically depicting the Hupa

people.

One Tolowa youth stared at a

male mannequin opening day and excitedly told a friend, "See

that headdress? That's just like mine. That looks like my tribe,

too."

Against the back curved wall

-- the building is entirely nonlinear -- is a small video screen

set in an open case lined with familiar river rock. On the screen

is a short video that plays continually. With a backdrop of spectacular

scenery from the Hoopa Reservation, Merv Sr. explains the healing

brush dance held in the church house. Melodie George talks of

the significance of the Flower Dance for young girls coming of

age, a dance that has been resurrected after a 25-year gap. Wendy

George tells visitors of the challenges facing basket makers

today because of herbicides on the basket reeds that are run

through the weaver's mouth as they work.

But it is Merv George Jr., a

fisheries specialist, on video who leaves a powerful and lasting

impression -- that this museum is about current events and issues,

not just the past. He explains that the Hoopa Reservation, the

largest is California, is dependent on the Trinity River.

"It is who we are. It runs

directly through the reservation like blood through our veins,"

he says. Yet today the tribe's life and culture continue to be

disrupted, threatened -- out of balance -- due to water diversion,

he says.

In 2001, on the third day of

the White Deerskin Dance, the dancers entered their dugout canoes

for a trip up the Trinity. That day, due to low water flows,

one canoe hit a rock, became stuck and began taking on water,

forcing the dancers out of the boat.

So the Hupa continue to dance

and pray for water to be returned to the river. In the meantime,

Merv George Jr. says, they are forced to periodically apply to

the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation to release more water from federal

government's dam upstream just prior to their sacred dances so

the canoes won't bottom out, throwing the ceremony -- and their

world -- out of balance.

MORE PHOTOS

BELOW

Poisoned

Relics

by

BOB DORAN

SEVEN-YEAR-OLD MERV GEORGE III,

GRANDSON OF the Hupa's keeper of regalia, walked proudly in the

procession celebrating the opening of the National Museum of

the American Indian last week wearing a traditional headdress,

a brilliant splash of red and white made by his father, Merv

George Jr., from white deerskin decorated with dozens of shining

woodpecker scalps.

![[Historical photo of four Hupa dancers]](cover0930-jumpdance.jpg) A

similar headdress is stored in the Hoopa Tribal Museum on the

reservation. Double-wrapped in plastic bags, it's stashed away,

never to be worn. Even handling it requires protective gloves

since some long-forgotten cultural anthropologist treated it

with poisonous chemicals. A

similar headdress is stored in the Hoopa Tribal Museum on the

reservation. Double-wrapped in plastic bags, it's stashed away,

never to be worn. Even handling it requires protective gloves

since some long-forgotten cultural anthropologist treated it

with poisonous chemicals.

[Right: Historical

photo showing traditional headdresses made from white deerskin

decorated with dozens of shining woodpecker scalps from Jump

Dance held in Pecwan, Humboldt County, circa 1900.]

It's a dilemma faced by tribes

all over the United States. Federal law now allows them to retrieve

long lost artifacts stored in museums, but they often find the

objects, once vital elements of their culture, tainted by chemicals

used to preserve them.

An important element in the

Hupa religion is keeping the world in balance, a process that

involves periodic renewal ceremonies including the Jump Dance

and the White Deerskin Dance. Both involve ceremonial objects

and regalia. While some of the regalia has been passed down from

generation to generation, pieces were lost over the years, seized

by the military or sometimes traded away when times were hard.

The Native American Graves Protection

and Repatriation Act, signed by the first President Bush in 1990,

requires federally funded institutions like the Smithsonian to

return sacred objects and human remains, but not other artifacts,

to the tribes they were taken from.

Passage of the law allowed the

Hupa to seek the return of a number of ceremonial items -- headdresses,

dance costumes and baskets -- many of them taken away in the

early 1900s at a time when the federal government was trying

to "civilize" tribes by outlawing many of their cultural

practices.

Merv George Sr. recalled stories

about when the troops left. "They took wagon loads of this

stuff that they confiscated from people, loaded it up and headed

out."

Some of the tribe's artifacts

ended up in the collection of the Peabody Museum at Harvard University

in Cambridge, Mass. A few years ago David Hostler, who served

as curator for the Hoopa Tribal Museum, obtained an inventory

of the Peabody's holdings and traveled to Harvard to reclaim

items that once belonged to the tribe.

Hostler said he was surprised

when he arrived at the museum. Before he could look at the Hupa

pieces, museum officials insisted that he put on gloves and a

mask for protection from toxic materials.

"Some of the stuff [had

been] sprayed with arsenic and mercury and whatever else,"

said George. Turn-of-the-century museum curators, using preservation

methods from a time when awareness of toxic substances was negligible,

had rendered the Hupa sacred artifacts poisonous. In particular,

George recalled the woodpecker headdress.

"We can't use it,"

he said with a note of sadness. "It was so full of this

stuff, it was just oily. If you put it on, [the poison] goes

in your pores because you sweat. It's up in Hoopa in the museum,

but they've got it all wrapped up."

George said the tribe's relationship

with the Smithsonian is different, and the Hupa have not asked

for the return of items from its collection.

"Some people [think] we

should get all of it back. But I'm one who feels that I can work

with them. Maybe they could send the stuff when we dance. I could

tell them what we need ... and maybe [they] could send me some

feathers or a Jump Dance basket."

The loan-back idea was put into

practice a few years ago when George's granddaughter celebrated

her coming of age with a traditional Flower Dance.

In response to George's request,

a representative from the Smithsonian flew out to California

and hand delivered a woven hat to be used in the ceremony.

"They brought me a flower

dance hat. We danced for her and I wore it," George said.

"It was more or less a symbolic gesture on their part. I

gave it back and they put it back in the museum."

PHOTO

ALBUM

Washington, D.C.

Opening of the National Museum

of the American Indian

![[Yurok tribal members holding banner that reads "Save the Klamath Salmon - The Yurok Tribe of California"]](cover0930-Klamath.Salmon.jpg)

A number of the Yurok made the long trip to Washington, D.C.,

for the museum opening festivities; they took time to lobby for

more water for the trouble Klamath River.

![[Three Karuk women]](cover0930-Karuk.jpg)

Representing the Karuk tribe were (left to right) Lena Bommelyn,

Pimm Allen and Lyn Risling, granddaughter of David Risling.

![[Dancer with feather headdress]](cover0930-dancer.jpg) ![[Young woman in costume]](cover0930-MissIndianWorld.jpg)

![[Older woman in Seattle costume]](cover0930-Seattle.jpg) ![[Man in feather headdress decorating hair of other man]](cover0930-PlainSoAmerica.jpg)

![[Four men in feather headdresses, playing drums and singing]](cover0930-plains.jpg)

Tribes from throughout the western hemisphere began gathering

on the National Mall soon after daybreak Sept. 21. More than

25,000 Indians representing 400 tribes took part in the procession

that wound its way east toward the Capitol and its new neighbor,

the National Museum of the American Indian.

![[Museum exhibit wall with photos of curators]](cover0930-exhibit.jpg)

A wall outside the exhibit listing the curators includes Merv.

George Sr. and David Risling.

![[museum exhibit behind glass of manekins wearing regalia]](cover0930-manekins.jpg)

Regalia that is most often used for the Jump Dance, a ceremony

that last many days and is used in hopes of driving away evils

such as sickness and war, to restore balance.

![[museum exhibit behind glass of manekin wearing white deerskin dance costume and drawing of the dance]](cover0930-whitedeerskin.jpg)

The White Deerskin Dance is performed every other year and is

used to pray for success in the gathering of fish, deer and other

sustenance.

![[outdoor video screen with image of W. Richard West speaking]](cover0930-RichardWest.jpg)

W. Richard West Jr., the museum's director, delivered a blessing

in the native tongue of his tribe, the Southern Cheyenne, then

translated it into English: "The Great Mystery walks beside

you and walks beside your work, and touches all the good that

you attempt."

![[Video image of Melodie George and caption"These houses, these xonta, are very sacred to us."]](cover0930-melaniegeorge.jpg)

Melodie George explains the significance of xonta, the cedar

plank houses the Hupa used to live in. They are now used for

ceremonial gatherings such as at the beginning of the White Deerskin

Dance.

IN

THE NEWS

| GARDEN | THE HUM | CALENDAR

Comments?

© Copyright 2004, North Coast Journal,

Inc.

|