|

by BOB DORAN

ROY PARVIN'S HOUSE

IS AT THE very end of a country road on the outskirts of Fortuna.

Parvin lives there with his wife, Janet, and two border collies,

Maggie and Kody, in a house surrounded by woods -- and by pieces

of the past. In the front yard there's an old drinking fountain,

the grade-school kind with a white enamel bowl where the water

bubbles straight up. Nearby is an antique gas pump, a relic from

an old service station. Tucked away in the two-car garage are

Janet's old Nash Metro, and Roy's 1954 Chevy pickup, vehicles

that seem to go with the pump. A path leads from the house to

Roy's office, an outbuilding adorned with a large set of antlers,

where he recently completed his second book, a trio of novellas

titled In the Snow Forest.

![[photo of Roy Parvin]](cover0921-roy.jpg) Critics praised Parvin's first book,

The Loneliest Road in America, a collection of short stories

set in the Trinity Alps. It was listed as an "editor's choice"

in the New York Times and the San Francisco Chronicle

when it was released in 1997, and that initial success led to

a two-book contract with publisher W. W. Norton. Critics praised Parvin's first book,

The Loneliest Road in America, a collection of short stories

set in the Trinity Alps. It was listed as an "editor's choice"

in the New York Times and the San Francisco Chronicle

when it was released in 1997, and that initial success led to

a two-book contract with publisher W. W. Norton.

But when In the

Snow Forest hits bookstores nationwide next month, the new

book should quickly reach a much wider audience than his first.

That's because Parvin has been selected by Barnes and Noble as

a "discovery author." His book will be featured in

Barnes and Noble's national advertising, in displays at stores

and in a prominent position on the store's website, barnesandnoble.com.

Parvin's work shows

a definite progression. In his new work, he moves from the short

story to the novella where the characters have more depth and

readers stay with them longer. His third book, already in progress,

is a novel.

"The industry

definition says a short story is 25 pages or less, a novella

is longer than 50 pages, a novel is over 150 pages. But none

of those rules is hard and fast. More has to happen in a novella

than in a short story. I think that more has to happen in a novel

than in a novella. You have to take the reader on a bigger journey."

For now the journey

he is crafting in his novel must be set aside for another kind

of trip. Roy, Janet and dogs are heading out on a nationwide

book tour to promote In the Snow Forest. Parvin will give

readings and sign copies at bookstores across the country. The

tour begins close to home with a party at Northtown Books in

Arcata from 2 to 5 p.m. Sunday, Oct. 1.

Parvin was born and

raised in New Jersey. When he was 18 he went off to Swarthmore

College to study history.

"That's where

I met Janet 23 years ago," he said. The couple moved to

New York where Roy studied film criticism at New York University.

"Then I realized

that I did not want to be a film critic. And I didn't want to

pursue film from behind the camera because I don't really like

collaboration."

He found work writing

and ironically it was a form of film criticism -- sort of. He

worked for the cable channel Home Box Office reviewing movies.

"It was fun for

the first six months, but after a while I got tired of sitting

in the dark watching bad movies. The reviews generally had to

be positive and that was difficult when it came to movies like

"Rocky II" or Bo Derrick's "Tarzan." It was

fun when I could sneak in little zingers that most people wouldn't

notice, but living in New York got to be boring.

"We both got

tired of the lack of space so we just packed up the car and drove

west. The car died in North Platte, Neb., a victim of some bad

gas. We just left it there, rented a car and kept going."

The end of the line

was as far west as they could drive -- San Francisco -- and the

city became their home for 15 years. Janet worked in book production

for Sierra Club Books. Roy once again made money as a wordsmith,

but he emphasized, "I was not working as a writer."

The work, creating manuals for high tech companies, was mostly

targeted at engineers.

![[photo of Janet Parvin]](cover0921-janet.jpg) Janet Parvin Janet Parvin

"Somehow I was

able develop an understanding of these arcane high tech devices

and write about them. It was actually good training for writing

because I had to become a good researcher."

The work was free-lance

which meant he had the freedom to set his own schedule and whenever

possible he and Janet would escape their urban environment.

"The city was

getting more and more crowded and we would go away every single

weekend. It evolved to the point where I was spending less and

less time working. We bought this property in the Trinity Alps

and we'd go up every single weekend."

A couple of things

happened that made him rethink his path in life. A close friend

was diagnosed with leukemia, which reminded him of life's fleeting

nature. And then there was trouble in Coffee Creek where they

had their cabin.

"A gold miner

wanted to open a mine right near our property. I started this

letter-writing campaign. A bunch of our friends had visited us

there and I asked if they would help, but I realized that they

were too busy with their lives to send letters to the Secretary

of the Interior and all these other people.

"So I said, `What

if I write a letter for you and do it the way you would write

it. Would you sign it?' So I wrote these letters. One would be

in Jim's voice, another was in John's voice, then Julie's. Each

person's was different.

"And it worked.

The gold miner gave up, called off his plans. After I was done

I was feeling full of myself. It was a lesson in writing in voice,

an important lesson for any writer."

The time was right

for a change. In 1993 Roy stopped doing business writing and

devoted all of his time to writing short stories. After 10 months

had passed he had completed 10 stories, but he hadn't sent any

off to publishers.

"I thought the

stories were pretty good but I didn't know whether anyone else

would. I knew I was getting better. I thought the tenth story

was the best I'd ever written."

Janet offered encouragement

--a little push. She suggested he attend a writing workshop in

the Napa Valley.

"I didn't really

know anything about conferences or writing schools, but I went

off to this workshop. I didn't have any expectations."

Those attending were

asked to send in a story for discussion. Parvin sent his favorite,

"May," a dark tale about a woman miner set in the Trinity

Alps. He found that people liked it. In fact he said, "The

response was galvanic."

Pam Houston was among

the writers on the workshop faculty. She is an award-winning

author whose book, Cowboys Are My Weakness, was a runaway

hit, at least in terms of short story collections. Houston was

so taken with Parvin's story that she became his champion.

"Pam carried

my story around like an orphan that needed a home. She showed

it to a publisher, Chronicle Books, and they called me up. They

said, `How many good stories do you have?' I knew that that story

was different from all my others, so I said, `I only have one

good story.' It was a smart answer. Most people are in a tremendous

rush to get published. But I knew that there was something about

that story.

![[photo of Roy and Maggie]](cover0921-dog.jpg) Roy and Maggie in front of

his writing studio. Roy and Maggie in front of

his writing studio.

"I heard it like

a song in my head. But when I wrote it down I couldn't reproduce

what I had heard. I kept on trying and getting closer and closer

to what the story was. The stories I had written before that

were basically first drafts. When I'd get to the end I'd say,

`I'm done.' This story kept getting away from me.

"I spent a month

on it working eight hours a day, seven days a week, writing and

rewriting. Then one day I got the first sentence down, and it

was like I knew the rest of the melody. I knew where the story

wanted to go and followed it. It was as if the story were being

told to me. I had found the voice. I knew that I had created

something that was bigger than anything I had done before."

He followed the "May"

story with 10 more tales of life in the Trinity Alps. For the

most part the characters are outsiders, loners like the troubled

Vietnam veteran in "Smoke" who disguises the marijuana

plants in his mountain garden by painting the leaves in "Technicolor

shades." Then there's the game warden in "Trapline"

who sets illegal traps.

For the most part

Parvin is not like the characters in his stories.

"I think I gain

access to them for a period of time. Like in the first story

("Betty Hutton" in In The Snow Forest), having

a big guy who the world thinks of as violent or dumb, but who's

not. You explore how it would feel to be that person. That's

what drafts are for, to explore.

"In the end it

seems like the story sprung from my head, but I probably wrote

4,000 pages to get there. For the title story I wrote 10,000

pages. In a way that's a misleading number, because a lot of

that was working on the first paragraph over and over and over,

printing it up and printing it up again, seeing what it's like

without the word `of' in there, and what has to change when I

move `of' from here to there. I literally write these stories

sentence by sentence and word by word."

"Betty Hutton"

is a picaresque tale about a parolee named Gibbs, "an antique

dealer gone bad," Parvin says.

"I like old things,

but not the kind of curios and antiquities that Gibbs likes.

I knew Janet used to work with someone whose husband sold curios.

So I talked to him about it and he gave me catalogue after catalogue

filled with Roman carnelians and stuff from the Shang Dynasty."

In the course of his

journey Gibbs meets an ice fisherman. (All three novellas include

scenes in snow country.) Getting the details right required a

bit of research.

"I've never gone

ice fishing. It's always fascinated me and I've done a lot of

other kinds of fishing, but not ice fishing. I bought 16 books

on ice fishing, read them completely, then talked to some ice

fishermen. Now people who have read the story are calling me

up asking when I'm going ice fishing again. When I say I've never

done it, they don't believe me.

"There's an old

adage in writing that says, `Write what you know.' Most aspiring

writers take that as an excuse for writing autobiography. I see

writing as an excuse to become a student of the world."

Elements from life

around him show up here and there. In the third novella, "Menno's

Granddaughter," the main character drives a Nash like Janet's.

Maggie the dog turns up in a couple scenes. But Parvin denies

that the characters he creates are veiled versions of himself.

"I basically

write the kind of stories I like to read. Maybe that's why my

stories aren't really autobiographical. I don't want to read

about myself, I want to read about other people. That's the exploration,

learning about what makes a person like this tick.

"I get to visit

with these people for a very intense period for three or four

months at a time. People ask, `Well, what happens after the story

ends?' I really don't know. "

|

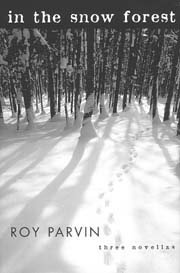

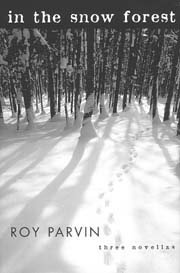

An excerpt from the title story in Roy

Parvin's new collection of novellas, In the Snow Forest. An excerpt from the title story in Roy

Parvin's new collection of novellas, In the Snow Forest.

Autumn: already the sad loss of autumn.

That fall the Trinities were

empty of men, Darby the only one left. The only one who didn't

sign on with the logging teams when a private timber concern

came through back in August, an outfit operating north out of

Cecilville, high and far in the granite hills, the rare opportunity

to fell the big sticks till the first snows. He'd had an injury,

his shoulder, and were it not for that, the insurance money still

flowing to him because of it, Darby would have assuredly been

with the rest, making the sawdust fly.

It was a last hurrah and who

knew when the next such opportunity would come along. Ever since

the door to the woods got shut and the public lands forever closed

to logging, the crew looked to a man as if they'd woken up late

only to find they'd slept through the best part of a movie. And

now here they were, knocking the rust off their saws after all

these years, leaving Darby behind with the women and children.

There was one woman and her name

was Harper and on Tuesdays Darby lunched with her at the Yellow

Jacket, the only eating establishment in forty miles. All Harper

had was an afternoon, one day a week, the hours a nurse from

county public health made the long drive under the trees to check

on her kid. Darby didn't know exactly what was wrong, only that

it was terrible, an obscure bone malady, and worse.

The crew had put him up to it,

at the fare-thee-well at the Timbers the night before they shoved

off, more than one of that lot telling him to look after her.

Darby and Harper had never been what might be called friends,

him only one of the hurly-burly of desperate men who orbited

her on their nights out. She'd fallen in with the crowd the way

those things happen, after Adcock quit her and the Trinities

for good. "I could use a drink of a certain description,"

she'd tease the crew slyly. And then once the initial rounds

were slammed down, "Boys, I'm about two shots shy of wonderful."

They lunched on egg sandwiches

and curly fries, watched the fixed-wing planes etch sky above

the bowl of mountains, the lazy approach over the lake, its surface

cupping from prop wash and then touch down at the midget flyway

a stone's throw away. From behind the swinging doors, the clatter

of Lynette in the scullery, the air heavy with salt and fried

cooking.

It was only one day a week, devoid

of romance, unlike anything Darby had known before. The things

Harper told him -- he could not make sense of them any more than

he understood how the world spun, what drew her interest, the

stories, her crazy stories. Sometimes she looked as if she wanted

or needed something from him and he couldn't for the life of

him guess what that might be.

|

IN

THE NEWS | EDITORIAL | CALENDAR

Comments? E-mail the Journal: ncjour@northcoast.com

© Copyright 2000, North Coast Journal,

Inc.

|

![[photo of Roy Parvin]](cover0921-roy.jpg) Critics praised Parvin's first book,

The Loneliest Road in America, a collection of short stories

set in the Trinity Alps. It was listed as an "editor's choice"

in the New York Times and the San Francisco Chronicle

when it was released in 1997, and that initial success led to

a two-book contract with publisher W. W. Norton.

Critics praised Parvin's first book,

The Loneliest Road in America, a collection of short stories

set in the Trinity Alps. It was listed as an "editor's choice"

in the New York Times and the San Francisco Chronicle

when it was released in 1997, and that initial success led to

a two-book contract with publisher W. W. Norton.![[photo of Janet Parvin]](cover0921-janet.jpg) Janet Parvin

Janet Parvin ![[photo of Roy and Maggie]](cover0921-dog.jpg) Roy and Maggie in front of

his writing studio.

Roy and Maggie in front of

his writing studio. An excerpt from the title story in Roy

Parvin's new collection of novellas, In the Snow Forest.

An excerpt from the title story in Roy

Parvin's new collection of novellas, In the Snow Forest.