|

IN

THE NEWS | CALENDAR

![Working on his legacy: Sam Swanlund at 71 [photo of Sam Swanlund hand-coloring photo of Carson Mansion]](cover0912-photohed.jpg)

by BOB DORAN

SAM SWANLUND GAZES OUT HIS LIVING

ROOM WINDOW at a panoramic view of Humboldt Bay, in what might

seem to be a moment of repose. It's an illusion. He is still

for a moment, patiently waiting for the photographer to get his

shot, but undoubtedly his mind is racing through the long list

of things he has to do.

At 71, Swanlund is ostensibly

retired -- he sold the Eureka camera shop that bears the family

name 15 years ago -- but he's still a very busy man. On the Wednesday

afternoon when we spoke, he was in the middle of several projects.

He is very active in his church, and there were numerous last-minute

arrangements for a succession of evangelists who were coming

to preach. His duties included publicity and shooting some photos,

and since he had not used his camera for a while, he was getting

it ready.

Swanlund was also preparing

to teach a course on the fundamentals of photography for Humboldt

State's Extended Education. It was less than two weeks away,

but he didn't seem too concerned.

Then

there is the work that he refers to as his "legacy to the

community." He may have left the camera and photo-finishing

business behind, but photographs are still a passion. A studio

next to his hilltop home is crammed to the rafters with works

in progress: oversized prints depicting scenes from early in

the 20th century that he hand colors in meticulous detail. The

black-and-white photos, most of them blown up from 5-by-7 inch

glass plate negatives, are transformed under Swanlund's brush

to become works of art -- just don't describe them that way within

earshot of Sam. Then

there is the work that he refers to as his "legacy to the

community." He may have left the camera and photo-finishing

business behind, but photographs are still a passion. A studio

next to his hilltop home is crammed to the rafters with works

in progress: oversized prints depicting scenes from early in

the 20th century that he hand colors in meticulous detail. The

black-and-white photos, most of them blown up from 5-by-7 inch

glass plate negatives, are transformed under Swanlund's brush

to become works of art -- just don't describe them that way within

earshot of Sam.

You'll find these colorful views

on display at a number of area businesses: Pierson's Building

Supply has a few, some of his first efforts are hung at Angelo's

Pizza, the Humboldt Bay Inn has one in its lobby and Swanlund

is working on a set that will decorate the inn's rooms.

All of the photographs show

views of Humboldt County, the community Swanlund calls home.

SHREWD --

JUST LIKE DAD

"I'm one of those few who

was born in Eureka: February 1931 at the old St. Joseph's Hospital

on G Street," he says with pride as we settle into comfy

chairs in his living room.

Sam's father, Oscar Swanlund,

moved here just after World War I to work as an accountant for

the railroad. "Then for some reason he decided he wanted

to be a photographer, so he bought the Alex Holmes Studio in

downtown Eureka in 1925. It was a portrait and commercial studio.

"I

don't know what it was about the business that interested him

or how he got started, but he did very well. I don't think he

was the best photographer around at the time, Ed Seeley was.

But my father was the best businessman; by far. The others

[in the photo business] would come to him all the time wanting

to go into partnership, and he always declined. He was hard-working,

fiscally conservative and very active in the community." "I

don't know what it was about the business that interested him

or how he got started, but he did very well. I don't think he

was the best photographer around at the time, Ed Seeley was.

But my father was the best businessman; by far. The others

[in the photo business] would come to him all the time wanting

to go into partnership, and he always declined. He was hard-working,

fiscally conservative and very active in the community."

It might go without saying that

Oscar instilled his values in his sons. Sam could be describing

himself.

"The business kind of grew;

my brothers both worked there and so did I," he continued.

"My brother, David, set up a laboratory that did a lot of

the photo-finishing for Northern California. My other brother,

Lorrie, went into real estate, but we all stayed here. I guess

that's a bit unusual.

"Even though I went away

for the service and for school, I always intended to come back.

This is my community. It's where I wanted to be. Most of my friends

who went away to the university would say, `I'm not going back

to that hick town.' Now, 50 years later, I'm noticing they're

showing up." He laughs in punctuation. "I always wanted

to be here, always."

Swanlund joined the Army around

the time of the Korean War. He's not sure why, but he was assigned

to the Army Security Agency and trained as a cryptographer or

as the Army put it, "crypt analyst."

While his unit was kept far

from the fighting, his preparation for the assignment included

training in hand-to-hand combat. It's a skill he has never had

to use, although he feels that the knowledge reinforced his self-assurance,

a key component in salesmanship. And Swanlund is a salesman par

excellence.

Asked how he ended up running

the family business, he admits that it was not his original plan.

He had entertained thoughts of becoming a dentist and, after

returning from overseas, made arrangements to attend the University

of California, Berkeley. Then he realized that dentistry might

not be an ideal career for someone who enjoys talking to people

-- and getting a response.

"I didn't really intend

to get into the photography business. When I came out of the

service in 1955 my father said to me, `Why don't you work for

me until it's time to go back to school?' It was just from February

until September, so I said, `Fine.' Thirty-two years later I

sold the business."

In 1958, after working for his

father for a few years, Sam took over the store. "He didn't

give me the business, I bought it," he explains. "And

I gave the going interest rate. That's as it should be."

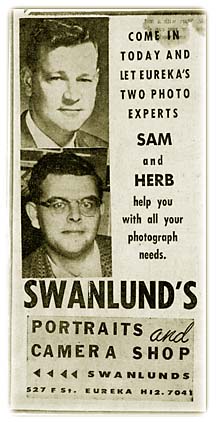

Sam had enlisted a partner,

Herb Frahman. "I didn't want the loan; I thought it would

be too consuming, so I asked Herb if he would like to be a partner.

He said, `Yes,' and we were partners for 20 years. We worked

hard, but we had a good time. That's what it's all about."

In

1987 Sam sold Swanlund's Camera to Fortuna businessman Patrick

O'Dell, and the camera shop and photo-finishing business became

part of the Humboldt Group. In

1987 Sam sold Swanlund's Camera to Fortuna businessman Patrick

O'Dell, and the camera shop and photo-finishing business became

part of the Humboldt Group.

Swanlund started a new career

in what he refers to as "corporate America." Primarily

he worked on "community relations" for timber giant

Louisiana-Pacific. He did public relations, photography, "tons

of aerial work" and put together a company newsletter.

"They were hardworking

people and I was raised on the work ethic, so it worked out great

for me, hopefully for them too. I got to travel a lot and met

many interesting people.

"I thought of it as a good

way to round out the end of a career. That's what I thought anyway;

it didn't work that way. I still work," he says, concluding

the thought with a short laugh.

STUMBLING

INTO A PASSION

Swanlund spends hours at a time

in his workshop, a rustic log cabin next door to his home. [photo above]

Inside, every available surface is crowded with work in various

stages: large photographs ready to be painted, partially painted

or done and awaiting framing. (He makes the frames himself.)

The source material for the

bulk of his hand-painted photos is a collection of 5-by-7 inch

glass-plate negatives, the work of a photographer, Ray Jerome

Baker, who had a photo studio in Eureka from 1904 until 1910,

then moved with his family to Hawaii. In addition to portrait

work, Baker photographed the towns and villages, the redwoods,

workers in the lumber and tanbark industries, shipbuilders and

shipwrecks.

The Corinthian

on the north Humboldt Bar, June 11, 1906, photographer unknown.

"Two men, Carl Christensen

and Lloyd Stine, kept bringing these glass-plate negatives into

the shop and I would make contact sheets for them," Swanlund

recalled, explaining that the men had met Baker in Hawaii and

bought the man's Humboldt work bit by bit.

"I finally asked them what

they were going to do with them. They said, `Oh, I don't know,

do you want to buy them?' I said, `Well, maybe.'" Without

much dickering they agreed on a price. "I paid each of them

$500 and received in return almost 1,400 glass-plates negatives

by R. J. Baker -- and he was good.

"I had something in the

back of my mind. I had two children in private school and it

was killing me, it was very expensive. I thought if I got an

old enlarger and took these plates and made big prints, my mother

could show me how to paint them, and I would sell them.

"I did two big ones and

took them down to the camera shop. Jerry Wilkenloh, who had Eureka

Title, walked in and wanted to buy them. He said, `How much?'

I said, `I dunno.' We settled on $195 apiece. That started this

whole thing."

While Swanlund initially got

involved with colorizing historic photographs as a business deal,

at this point it is more than that: He sees the work as his legacy,

a way to honor the community that gave him so much.

Milk cart on Arcata

Plaza, circa 1915,

photo by A. W. Ericson

Each hand-painted

piece is signed and numbered, and the editions are strictly limited:

He will only paint four copies of any particular photograph.

While there is an art to the work, he does not exactly see himself

as an artist.

"They're real -- not an

artist's conception -- real time and a real place and real people.

There's an art to it, but I don't think it's art."

Whether or not it's art, there

is painstaking research that goes into each piece.

"I did one of a street

car years ago. I ended up tracking down the man who used to run

the streetcar and asked him, `What color was it?' He said, `Tuscan

red.' I knew the color from my interest in trains, so I used

that color.

"I had noticed that it

had no headlight. I wanted to know why, so I called somebody

else. They told me it was because there was vandalism: During

the day kids were throwing rocks, knocking out the headlights.

What they did was put the headlight on at dusk every day before

they took off. How many people know that story? People think

vandalism is only something that happens today. No, it isn't."

In 1985, Swanlund donated the

bulk of the Baker plates, along with other photographs and negatives

from his collection, to Humboldt State University. His gift formed

the core of what is known as the Swanlund-Baker Photograph Collection.

A proviso of his donation was

the right to take home plates for his colorization work. But

he doesn't do that as much as he used to.

Arcata Wharf in

the late 1800s,

photo by A. W. Ericson

"As long

as I'm alive I can go over there and pick them up, but I pick

up very few -- I'm getting old."

It takes him about 60 hours

of intense concentration to complete a piece. "What surprises

me, at my age I still have an absolutely steady hand, and I use

the same glasses that I bought many, many years ago. I can still

do it, and maybe do it better.

"If I do a locomotive,

it is excruciatingly painful to get it done right, and really

make it look like a locomotive, as if you standing right next

to it. I know I've succeeded when I can reach out and feel the

metal."

The skill he is intent on perfecting

is an ability to use paints to "push and pull," as

he puts it, pulling the subject forward and pushing the background

back, where it belongs. It's something he learned to do when

taking photographs.

"The subject is what photography

is all about -- one subject, please, and [also] a secondary,

that's a must. The secondary could be a pattern, it could be

a color, it could be anything, but you must have a primary and

a secondary, no matter what it is. Then, simplicity. I always

pick simple ones, not complicated, because simplicity is the

key to art."

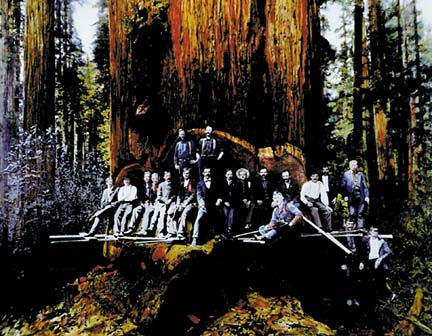

Vance Lumber Co.

crews at Lindsay Creek near Fieldbrook, circa 1897.

REMEMBER

YOUR AUDIENCE

At this point we have wandered

into his other area of interest -- teaching photography, something

he has done for "years and years and years" and something

he still does.

"I tell [my students] I

don't care if you take a garbage can as your main subject --

that's OK -- however, you must do it with craftsmanship. That's

my requirement. It's not what you take, but how well you take

it. And I apply that to the art world today. They've gone off

on a big tangent, and that includes photography.

"My attitude has always

been, `What does the customer want?' Now, if that's crass commercialism,

so be it. But I always go toward, `What do they want?,' not `What

do I want?'

"What you find is the person

whose does work to please the client or the viewer is still with

us. Ansel Adams, and others, were good and their work is still

valid."

"New Era Park,"

airport and racetrack south of Eureka, July 4, 1914, photographer

unknown.

Mention of the

great photographer turns the conversation to the Adams exhibit

upstairs in what was once his store. "That's Patrick's collection,"

he explains, referring to Patrick O'Dell.

It also stirs up a memory from

his days running Swanlund's.

"One day, long ago, we

were in the store, and a man walked in. I talked to him. He wanted

to buy some book. I said, `Yes, we have it.' We had a pretty

good-sized library at the time. I took him over and showed him.

He came back to the counter, bought it and left. I turned to

the others and said, `Do you know who that was?' They shook their

heads. I said, `It was Ansel Adams.' They didn't even know."

And, as is his habit, he punctuates the tale with his trademark

laugh.

Learn from a PRO

THE FLYER FOR SAM SWANLUND'S

HSU EXTENDED EDUCATION CLASS, "Fundamentals of Photography,"

promises: "Great photography can be taught!" In addition

to learning how to use a camera he offers instruction in "the

techniques of the Great Masters of painting to photography."

This has nothing to do with

hand-painting photos. It is largely based on information gleaned

from a little pamphlet called, "Better Pictures through

Good Composition" written by Ray Koken, a man who showed

up at Swanlund's Camera in the 1950s. Sam bought a few copies

to sell, then when he got around to reading it was so taken with

the way Koken had boiled down the rules of composition that he

ended up taking over distribution, and eventually buying the

publishing rights after the author died.

"It isn't that difficult

-- `make it simple' -- that's what I teach." At this point,

Swanlund shifts into full salesman mode, "I always promise

my class, `If you will listen carefully I will guarantee an increase

of 30 percent, where ever you are, professionals included, I

will raise your quality that much -- if you follow the rules."

Sam Swanlund's Extended Education

class "Fundamentals of Photography" runs from Sept.

17-Oct. 29, 2002 at Humboldt State. For information or to register

call 826-3731 or go to www.humboldt.edu/extended.

IN

THE NEWS | CALENDAR

Comments? E-mail the Journal: ncjour@northcoast.com

© Copyright 2002, North Coast Journal,

Inc.

|