|

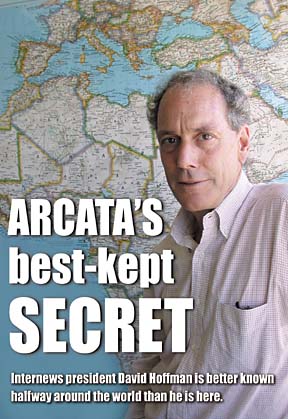

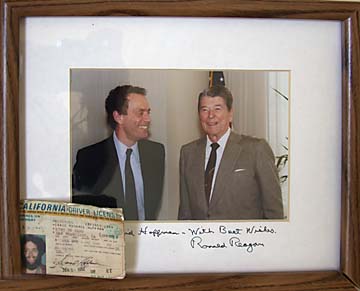

by KEITH EASTHOUSE STEPPING INTO THE WORLD HEADQUARTERS OF INTERNEWS, a media training and support organization with a $20 million budget and offices in 30 countries, is a disorienting experience. One moment it's foggy, tie-dyed, laid-back Arcata; the next it's a whirl of activity reminiscent of a high-level think-tank in Washington, D.C. Telephones ring, fax machines screech, people scurry about. A row of clocks high on one wall tells what time it is in San Francisco/Arcata; Washington/New York; Paris; Moscow; Almaty, Kazakhstan; Jakarta, Indonesia. Intelligent, pleasant faces look up briefly, smile, then bend back down to the tasks at hand. Something -- a lot -- is going on here. Several Ansel Adams prints lend an austere note, and a satellite image of the earth reinforces the global theme. Then it's into an office where a giant map of Africa plasters one wall. Less noticeable are two small photographs, one of Reagan, the other of Gorbachev, with the same guy standing next to them.

LEFT: Hoffman with Reagan. RIGHT: Hoffman (center) with Gorbachev In walks that guy, David Hoffman, president of Internews. He's busy, there's no doubt about that, but his engaging manner is immediately apparent. There's an exuberance about him, though he is graying and on this day appears a tad drawn as if not fully rested. Niceties are exchanged but Hoffman's an important man so the interview begins shortly. He handles questions with aplomb and openness. He waxes enthusiastic about a recent trip to Europe (the cause of the slight tiredness, perhaps). The journey, to Paris and Athens, grew out of a memo he wrote prior to the Iraq war warning, presciently, that security problems could hamper the establishment of an independent media in post-conflict Iraq. Not long after circulating it, Hoffman got a call from an official with the Office of Transition Initiatives, part of the U.S. Agency for International Development, a major Internews funder. The official proposed that Hoffman "draft the media laws for Iraq." Hoffman said he and his organization wouldn't want to do that -- the job should be done by the Iraqis themselves. But he said Internews could get the process going. Soon, six or seven media experts -- including two Iraqis, the man who wrote Russia's media regulations and the Britisher who had been "media commissioner" in Bosnia and Kosovo -- gathered in Cairo. Meeting under the auspices of the Cairo Institute for Human Rights Studies, the group produced what was essentially a manual for how a country like Iraq with no tradition of a free press could build one. "They wrote a fantastic document. It's a textbook example of how to do this," Hoffman says. Hoffman and other Internews officials made the existence of the document known to various media people here and abroad and proposed an international conference. The proposal immediately met resistance. The war hadn't even started and the U.S. was funding an effort about what Iraq's post-war media should look like. Given the extent of anti-American sentiment in Europe over Iraq, it quickly became clear that other governments had to back the conference or it wouldn't happen. In a testament to the growing influence of non-governmental organizations like Internews, such backing was not long in coming. The governments of Germany and Russia, despite their opposition to the war, agreed to act as co-sponsors, as did UNESCO (the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization). The Greek government, meantime, holder of the European Union presidency, came forward and offered to host the event. (That an Internews board member of Greek descent has connections with the Greek government was not entirely irrelevant.) With such multi-national backing, Arabs with an interest in seeing the establishment of an independent press in Iraq suddenly had "cover," in Hoffman's words, to participate. And so, at a time when European-American relations were in tatters, when the U.N. Security Council had come apart over the buildup to the Iraq war, Hoffman's memo, written in his Arcata office, had led to a diplomatic coup. The three-day conference took place, in Athens, in early June. Seventy-five media experts, two-thirds of them Arab, were in attendance, and they strongly endorsed, with some minor modifications, the Cairo document. The next step, Hoffman says, leaning forward in his office chair, is to get the "buy-in" of influential Iraqis who never left the country. (The Iraqis who drafted the document, as well as those present at the Athens conference, were largely exiles.) Then the document, the framework for Iraq's media future, will be presented to L. Paul Bremer III, the chief American administrator in Iraq, for his endorsement. Hoffman smiles. "I get a kick out of the ability to live here with this lifestyle, with my friends here, and be able to affect things in the world. I get such a kick out of that." Coming-out party One suspects Hoffman has also gotten a kick out of the incognito status he and his organization have long had locally. Until recently, Internews operated out of a historic, 19th-century clapboard house at the corner of 8th and J streets across from the Arcata Co-op. For years, a small wooden block near the front door bearing what for most was the cryptic word "Internews" was all that announced the organization's presence to the community. Why the low, practically nonexistent profile? Rick Garza, vice-president of finance and administration, said that a prominent sign made sense for a retail outlet but not for an organization like Internews. "There was no point [in having a big sign] since we don't have walk-in traffic," Garza said. Hoffman had a different explanation. "It's really my personality. Believe it or not, I'm ultimately a shy person. People would ask me what I do and I'd tell them about the size [of Internews] and it would distance them and I hated that." But times change and Hoffman, 58, has decided it's time to emerge from the shadows. This story is one example of that. Another is the organization's new headquarters just south of the Arcata Post Office at 876 7th St., formerly the site of P.C. Sacchi garage. Airy and spacious, sporting skylights and indoor fountains, the 7,000-square-foot facility is a far cry from the former digs, which while atmospheric were so cramped they couldn't house the whole organization. (The accounting department used to operate out of a small office in Sunnybrae.) But the most significant sign

of change is, well, the sign. The small wooden block is nowhere

to be seen on the building's eye-catching dark blue with orange

trim facade. In its place, in large silver letters stripped above

the door, is the word that has puzzled so many curious Arcatans

over the years: "INTERNEWS." The letters were put up

Monday, and the organization's logo -- a three-dimensional globe

wrapped in a ribbon -- should be located directly "With 30 [local] employees we're one of biggest employers in town now," explained Hoffman, noting that 10 years ago the size of the Arcata staff was a whopping three workers including himself. "I want to share this with the community. We get to affect the whole world. I want the community to know about us now." Hoffman's even throwing a coming-out party, albeit by invitation only. The open house will take place on Sept. 18 and will of course be located at the new facility -- which, by the way, was remodeled to Internews' specifications by Danco Builders and designed by local architect Kash Boodjeh. (Internews did not buy the building; instead, they are Danco's tenant.) One topic of conversation will undoubtedly have to do with what, for the Arcata staff, is a dreaded, or at least tedious, topic: What, exactly, does Internews do? The answer is so complicated that the typical response is to change the subject. "It's a running joke around here that the worst thing about working at Internews is trying to explain to people what you do," said Annette Makino, vice-president for communications. "I just don't" explain what I do, said Garza. A primer One way to make sense of Internews is to look at its staff. Among its 500 employees, doing work in 45 countries and based in offices stretching from Arcata to East Timor, are current journalists, former journalists turned administrators, media law experts, financial experts, communications personnel and support staff.

Another way is to look at where its money comes from: It is 80 percent funded by USAID and the State Department, with the remainder provided by high-profile private foundations such as the MacArthur Foundation. (The dependence on the U.S. government has raised questions in some quarters about whether Internews is overly vulnerable to government manipulation.) A third way to describe the organization is to describe what it isn't. It isn't a news gathering and news disseminating organization like this newspaper, the New York Times or CNN. Instead, its raison d'etre -- as Hoffman's efforts regarding Iraq illustrate -- is to promote the establishment of Western-style independent media, particularly television, in places where it has never existed before. Internews pursues this goal in different ways. One is to train people to be journalists -- not an easy task in countries with no tradition of a free press. A typical method is to hold workshops at which working journalists serve as teachers. Training sessions were recently held in Egypt, Jordan and Oman, and they proved quite popular. The one in Egypt, for example, attracted 300 applicants, according to Hoffman. (Only 20 slots were available.) A second approach is to provide technical and other forms of support to fledgling radio and television enterprises -- Internews' greatest success in this regard was to foster the development of independent television networks and stations in a place that had only known state-run TV: the former Soviet Union. The effort has had some recent setbacks. Early this summer, for instance, the Russian government shut down the last independent national television network, and a couple of years ago the popular news program NTV was also forced to close. However, Internews' strategy from the start was to focus on the little guys; as a result, Internews still supports 600 independent broadcasters in Russia that are either local or regional. That gives Hoffman hope that Internews' work in the country won't go to waste. "I think it's irreversible. They can shut down some big TV channels but they can't shut down the media per se -- there's too much of it and it's in the culture now. People will rise up." He cited a failed government shutdown effort last year not in Russia but in the former Soviet republic of Georgia. After an independent channel began to expose corruption in the Georgian government, officials attempted to shut the station down. In response, thousands took to the streets and the government fell. A third strategy is to assist countries in setting up the regulatory framework and laws that make an independent press possible. This is particularly critical with regard to television and radio, where there are a limited number of available frequencies. Consequently, a licensing entity like the Federal Communications Commission needs to be set up to determine who can broadcast. Other Internews initiatives include a program called "Local Voices" that's aimed at training journalists in Nigeria and Kenya to report on the difficult and delicate topic of AIDS; and an effort dubbed the Global Internet Policy Initiative, a partnership between Internews and another nonprofit to shape the legal and policy framework for Internet development in 16 developing countries, ranging from Eastern Europe to India. An associated venture, called the dot-GOV consortium, provides financial assistance directly to governments to encourage telecommunications and Internet policies that create universal access. Internews is not the only nonprofit in the media-building field -- a field that in the post-Cold War, Internet-boom era is burgeoning as more and more countries are hungry for access to information. Its competitors include the Washington, D.C.-based International Research and Exchanges Board (IREX), which has a broader focus (in addition to independent media, IREX fosters the other building blocks of civil society, particularly higher education); and the International Center for Journalists, another D.C.-based outfit that focuses narrowly on print journalism. But Internews, no one disputes, is the pioneer. Origins More precisely, the pioneer is Hoffman and a couple of "video crusaders" -- as Wired, the online magazine put it a few years ago -- named Kim Spencer and Evelyn Messinger (Spencer's wife). It was May 6, 1979, the day of the Ralph Nader-organized demonstration in protest of the Three Mile Island disaster. Some 200,000 people were marching in Washington, D.C. Hoffman was on the other side of the country, in San Francisco, where he was getting heavily involved in the growing anti-nuclear movement after having escaped civilization for a time by living barefoot out in the woods in Alderpoint. He happened to walk by a television set, and his eye was caught by something that at the time was revolutionary: a live satellite broadcast of the protest in Washington. Who did this, he wondered? The answer was Spencer, who had discovered that FCC laws allowed for the use of transponders owned by the Public Broadcasting Service at a cost of $400 an hour.

"He was the only guy who had ever used this law," Hoffman said. "He raised some money, got a bunch of video artists together, contacted all the PBS stations, and put it up on a satellite. The major markets took it. "He was using a PBS satellite to reach 5 million people for a totally political agenda," Hoffman went on. "It was a total breakthrough." It proved to be a life-changing moment for Hoffman, a former left-wing labor organizer whose work in the anti-nuclear movement was already getting bogged down in factional disputes. He gradually began to see an entirely new way -- one that was potentially vastly more powerful -- to effect change. "I came to the conclusion that the solution to the nuclear war riddle had to include the protesters and the Pentagon, the Russians and the Americans; you couldn't leave anyone out.

"The idea of using satellite TV was a natural," Hoffman added. "Satellite TV ignores boundaries and can link citizens directly." The trio founded Internews in 1982, which initially operated out of a house in San Francisco. Their first project was to compile an archive of films, TV shows and documentaries about the issue of nuclear war for use by independent producers and networks. Not long afterward they produced a series of satellite exchanges between Americans and Soviets that were called "spacebridges." The first took place at the Us Festival, a high-tech rock concert in San Diego sponsored by Apple Computer founder Steve Wozniak. The next year, 1983, they broke new ground with "Moscow Link," which joined top American and Soviet scientists in a discussion of the risk of a nuclear winter at a conference headed by Carl Sagan. More spacebridges followed, including the 1986 "Citizen's Summit," moderated by Phil Donahue and Vladimir Posner, a popular Soviet television personality; and, beginning in 1987, a series of spacebridges produced in association with ABC News and Soviet State Television which earned Internews an Emmy Award for technical direction and a nomination for outstanding news and documentary achievement. Peter Jennings moderated this series of seven programs, which ran until May 1990. The spacebriges with the Soviets turned out to be the key to Internews' future. When the Soviet Union fell, no one else in the United States had the Russian media contacts that Hoffman, Spencer and Messinger had. Making the transition to help journalists in Russia establish a free press was therefore, if not easy, at least natural. "Our advantage was that we already had working relationships with creative people" in Russia, Spencer explained in a telephone interview from the Bay Area. (A past president of Internews, Spencer is presently a board member.)

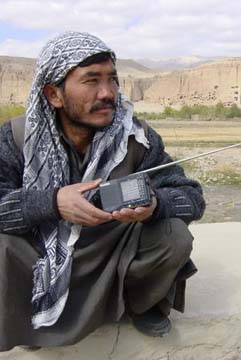

Internews trains local journalists in Kabul, Afghanistan

The funding dilemma There's no question that Internews today is a huge success story. But the heavy reliance on the U.S. government remains a sore point. David Anable, head of the International Center for Journalists, refused to criticize Hoffman or Internews. "I have great respect for David Hoffman," Anable said in a telephone interview from his Washington, D.C., office this week. "He was an activist 20-plus years ago, and he managed to transform that into a very positive effort to build up the world's media, particularly its radio and television, for the very constructive goal of strengthening the world's democracies." But Anable said that his own group has gone out of its way to avoid becoming as dependent on money from the American government as Internews. He said that the center gets 30 percent of its funding from the government -- that compares to approximately 80 percent for Internews. Anable cited two risks with overreliance on the U.S. government: "The appearance that you are bought and paid for and the difficulty of going your own way. "I believe a variety of funding, particularly non-government funding, gives us greater freedom of maneuver to say no to the U.S. government," Anable said. "I can say, `No, we don't want to do that,' without too many qualms because even if all the funding is taken away it wouldn't be a disaster," he added. Internews has taken steps to diversity its funding base, notably the hiring of a new director of development who's been responsible for landing a number of major grants from private donors in the last 15 months, including a recent $450,000 grant from the MacArthur Foundation, and a $750,000, three-year grant from the Knight Foundation. Nonetheless, Hoffman agreed that there is an appearance problem. "This is the fundamental contradiction of our work: We are funded by the U.S. government to create non-governmental media." But he said the problem isn't that Internews is in a position where it must do the U.S. government's bidding -- "I don't get much pressure," Hoffman said. The problem instead is the government's failure to distinguish between what Internews is attempting to do -- set up independent media -- and what other governmental agencies, particularly the military, wants to do -- issue propaganda to win hearts and minds. Pointing out that difference "is my constant mantra," Hoffman said, "I am constantly fighting that battle." That's more than just talk. In the last year or two, Hoffman has either authored or co-authored a series of op-ed pieces in publications like The Washington Post, The Baltimore Sun and USA Today. In the spring of last year, he wrote a lengthy essay in the prestigious journal Foreign Affairs. In all of these writings, the message has been essentially the same: The United States helps itself when it promotes independent media abroad, and hurts itself when it stoops to propaganda. "The United States will appear duplicitious if it tries to support independent news outlets while simultaneously manipulating information or engaging in counterpropaganda," Hoffman wrote in Foreign Affairs. Still an idealist When asked what the connection was between the barefoot hippie living in Alderpoint and the influential head of Internews, Hoffman turned reflective. He spoke of the left-winger who steeped himself in the history of the American socialist movement, the guy who adamantly believed that change from within is impossible, the guy who led protests in the latter stages of the Vietnam War. He spoke of his eventual realization that "any ideology is dangerous, whether religious or political," his conclusion that "conservatives are right on some things, like school reform," and his evolution into someone who doesn't just simply see the American military as something evil. "I've become much more of a hawk," he said. What he doesn't mention, interestingly, is the thread that seems to connect the young David Hoffman of the `60s and `70s with the one today: idealism, the belief that one individual can change the world. But then maybe he doesn't have to. He's doing it.

IN THE NEWS | PUBLISHER | CALENDAR

Comments? © Copyright 2003, North Coast Journal, Inc. |

underneath

its name by the time you read this story. Hoffman has gone from

hiding Internews to proclaiming it.

underneath

its name by the time you read this story. Hoffman has gone from

hiding Internews to proclaiming it.

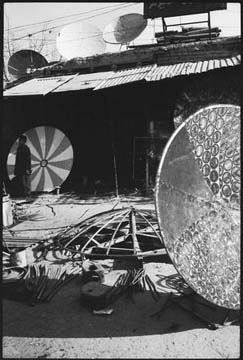

LEFT: Satellite dishes in Kabul, Afghanistan

LEFT: Satellite dishes in Kabul, Afghanistan