|

by EMILY GURNON IT WAS A YEAR AGO THAT Rachael Riness first noticed the brown decay on the tops of her daughter's front teeth. At the time, Riness was homeless and living in Santa Rosa -- far from her native Humboldt County. She brushed the little girl's teeth "as often as I had a toothbrush," she says, and beyond that, she didn't think about it. Other things, like how they would eat and where they were going to sleep that night, were more pressing. Besides, Riness thought, she'd be heading back to Eureka soon. "I'm thinking, I'll just take her to the dentist when I get home," she recalls. That never happened. "I got home and found out there was no dentist," Riness says. Everywhere she turned, the answer was the same: We don't take Medi-Cal.

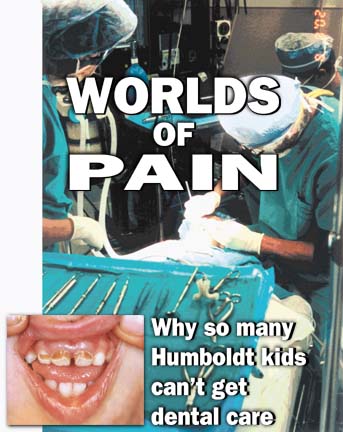

That leaves the clinic dentists, who number eight in the entire county. Three additional dentists at United Indian Health Services will see children if they can provide evidence of Indian heritage. But new patients have to wait an average of 11 months for an appointment. The other clinics typically have waiting lists of two to three months for returning patients -- and two are closed to new patients because they are booked for months to come. Most of the clinics try to work patients in in an emergency, but even emergencies may wait a week to get addressed. Southern Humboldt hasn't had a dentist who will take Medi-Cal since last December. "If you're low-income it's extremely difficult to get dental services," says Laura McEwen, oral health coordinator for Humboldt County. "The reimbursement rates for Medi-Cal and Healthy Families are very low. And there are very few dentists. Those things combine to really limit access." Add to that the difficulty in treating very young children -- who won't sit still in a chair -- and you have what local officials, providers and patients call a crisis. [a list of Humboldt-Hoopa-Willow Creek dental clinics that accept Denti-Cal and Healthy Families is at the end of this story] Oral surgery at age 3 "That's exactly what it is," says Darla Dale, a dental hygienist who works as the coordinator for St. Joseph Hospital's outpatient dentistry program, where the worst cases are handled in an operating room under anesthesia. "It's a real serious problem, because we do have clinics available to serve this community, but they're just as busy as I am," Dale says. "Our biggest problem in Humboldt County is that we have this huge, spread-out rural population and two pediatric dentists -- who are so busy with their private practice that they have no room to take on any more patients, private or Medi-Cal." The problem is not limited to 12-year-olds who've spent years gulping Cokes and noshing on Skittles. Many very young children suffer decay so severe that they cannot be treated in a dental office but must go to St. Joseph. Riness's daughter, Tazanna, was one of these children. Earlier this month, she underwent oral surgery at the hospital. Her two top front teeth had to be removed, along with another alongside it. She had seven additional fillings. Tazanna is 3 years old. She will spend at least three more years -- until her permanent teeth come in -- without front teeth. And she's not unusual. There may be hundreds of children in the same or worse condition, Dale says. In fact, most of the patients she has scheduled for surgery are near the age of 3; the youngest was 17 months. About 25 patients are on the waiting list. Parents who can't get their children in for regular visits to the dentist often wait -- not realizing the severity of the problem until their child's teeth are brown, crumbling or abscessing. We're talking, Dale says, about children in pain. "I had one child who went to the ER five times for a toothache before I got the child (into surgery)," Dale says. "She was 3. Sometimes you'll see children with complete decay, 17 out of 20 teeth, and they won't make a peep. But then there are those that it's painful every day. I have a mom calling me right now that her daughter's screaming every day about her teeth. This little girl's 4." Pain that severe becomes life-threatening; children will stop eating and drinking, Dale says. Some get a condition known as cellulitis, an infection that swells the face and can become deadly. There are other consequences. Children who lose baby teeth risk having the remaining teeth drift into the resulting space, which can affect the alignment of the permanent teeth. Missing teeth hinder speech development. And even for a very young child, having bad or missing teeth can take a devastating toll on self-esteem. "The child is labeled," Dale says. "Someone who doesn't have good dentition is frowned upon socially. It's big. People notice that." Children with bad teeth often don't want to open their mouths to answer questions in school or talk to classmates, according to a 2000 report by the U.S. Surgeon General titled "Oral Health in America." They are afraid to smile. They become socially isolated. Tazanna's mother, Rachael Riness, worries about this. "She's very much into taking pictures," she says of her daughter. "She's very much into being pretty and she doesn't like being different." Two nights after the surgery, she says, it really hit. "I looked at her mouth after it finished bleeding and -- I mean, look at this!" she says, gently lifting Tazanna's upper lip and fighting back tears. "That doesn't look pretty. I am so angry that my daughter had to lose her teeth."

From the above left, Tazanna Riness, 3, before oral surgery. Tazanna is held by Cindy Brehm, RN, prior to surgery as they wait for the perioperative sedative to take effect. This sedative helps children to relax before they are taken back to surgery and to be less frightened. Brehm comforts Tazanna as Dr. Rasoul Scholz administers the anesthesia. Below left, Tazanna at home after surgery.

A national epidemic Nationally, tooth decay is the single most common chronic childhood disease -- five times more common than asthma and seven times more common than hay fever, according to the Surgeon General's report. More than 108 million American children and adults lack dental insurance. Twenty-five percent of children do not get in to see a dentist before they start kindergarten. Poor children suffer the most. Children from families earning less than $20,000 a year have 10 times more unmet dental needs than children of families earning $50,000. About 27 percent of Humboldt County children ages 4 and under live in poverty.

Of 119 children examined, 88 -- nearly three-quarters -- had untreated cavities. In the majority of cases, the dentist found decay in more than just one or two teeth; 15 children, or 13 percent, had 10 or more untreated cavities. "We had one little kid who every tooth in his head had a cavity," says Barbara Davis, mobile dental coordinator for Open Door. The dental van treated most of the children, and referred some to the hospital dentistry program. A few never showed up for their return appointments. "They became homeless," Davis says. "They were actually in Eureka living in their cars." Other studies have yielded similar results; some have been less drastic. But so far, the surveys have been piecemeal. There has been no attempt to quantify the problem on a countywide basis. Even if there were, dental providers would be unable to take the next step. "The issue is, if we screen them all, we wouldn't have a place to send them," Dale says. "Then the parent has to figure out, `OK, what do I do now?' And then they do like Rachael and spend three days on the phone."

'My teeth are owies' Earlier this summer, after months of hearing Tazanna cry, "My teeth are owies!" Riness did find a dentist who would see her -- in Redding. She made an appointment and found a friend who could drive them there (she doesn't own a car). They couldn't afford a motel room, so the three travelers slept in the truck. But all of her effort was for nothing. When he examined Tazanna, the dentist said there was no way he could treat her. A child that young -- with so much decay -- would never sit still long enough. She would have to be sedated. Most clinics do not sedate patients because of the risks and the liability issues, Dale says. Rosie Weston sees the problem from the front lines -- often before anyone else. A nurse practitioner who works in Eureka and Humboldt County schools, Weston says that she is virtually powerless to help a child with dental decay. "A child coming in to a school nurse's office with a toothache is a school nurse's nightmare," she says. "You can pretty much fix bumps and bruises and blood. (But) when a child comes in with a toothache, it's just a whole different ball game. It just makes you feel sad. "Trying to get a child into a dentist is just almost impossible here," much harder than finding a medical doctor who will take Medi-Cal, she says. Weston usually refers children without insurance to the General Hospital Dental Clinic in Old Town, Eureka, which is owned by the state and operated by St. Joseph, or to Open Door's dental clinics in Arcata and Eureka. All three deal with walk-in emergencies, like toothaches, but help may not come right away. "You sit there and sit there and sit there, and if you're really lucky, they might see you," Weston says. "I've had kids sit there for hours and hours."

Not enough dentists

"The biggest problem is staff," Spetzler says. "It's not just recruiting the professional. It's often recruiting their spouse," who may find career opportunities limited here. They also want to know where the nearest Costco is, and can they see a movie if they want to, he says. "Those are the kinds of issues that sometimes make a difference." With so few dentists overall, it's no wonder that so many steer clear of Medi-Cal patients, says Tom Lewis, a dentist who ran his own private practice for 26 years and now works as the sole dentist at the Willow Creek Family Health Center, a St. Joseph Health Systems clinic that sees many low-income clients. "A private practice is a small business," Lewis says. "It has to make money for the dentist to survive." The dental portion of Medi-Cal, technically called Denti-Cal, pays a dentist at best about half of the standard fee -- not enough to make a profit, he says. And dentists are accustomed to making a good living. The web site of the American Dental Association boasts in its career information that the average dentist earns in the top 8 percent of family income. Given the tremendous need, dentists are afraid of opening the floodgates to low-income patients. "You start taking a lot of Medi-Cal, all of a sudden your practice becomes mostly Medi-Cal," Lewis says.

Avoiding low-income patients Tim Pentecost, president of the Humboldt-Del Norte Dental Society, says that many private dentists don't feel well-trained to see kids. Young patients can be unruly and hard to manage. They often need extensive work. But that doesn't mean the dentists aren't willing to help, he says. As a group, their No. 1 issue this past year has been how to deal with the overwhelming need for dental care among poor children. "It's not something that's on the back burner. It's the overriding concern for local dentists," Pentecost says. But "it's not going to be solved just by the dentists or someone throwing money at the situation. It needs to be a group effort." Garrison Tucker has been a pediatric dentist in Arcata since 1962. His practice, which he now shares with his son, has several hundred patients on the waiting list. But unlike many others, he insists the problem of untreated dental disease is "completely over-exaggerated." "I don't think there are that many kids out there in pain," he says. "We don't see that in our practice." When patients do come in with toothaches or other emergencies, they will try to work them in -- regardless of insurance status, he says. That may not filter down to parents like Rachael Riness, who -- when she tried calling the Tuckers' office on behalf of Tazanna -- was simply told that they weren't taking new patients and that Medi-Cal was not accepted. Nothing was said about emergency appointments being available, and Riness didn't know to ask. There are other reasons, besides money and the difficulty in dealing with kids, that make dentists shy away from low-income clients. "In this country, we have a class system and we don't acknowledge it," Lewis, the Willow Creek dentist, says. "Most dentists are middle class; most Medi-Cal patients are lower class: they're not educated, they may do drugs, they're not as responsible about appointments." The dentists who do take them "grumble and they gripe and say they're ne'er-do-wells, they don't come to appointments, they don't brush their teeth... A dentist doesn't need the hassle." Class differences also help explain why poor children get more cavities than those from wealthier families. Parents' lack of education about nutrition, how to care for teeth, and the importance of baby teeth is a major factor, says Linda Shepard of Northcoast Children's Services, a nonprofit that runs the federally funded Head Start day-care program for low-income preschoolers. The problem often starts when parents allow their babies and toddlers to carry around or sleep with a bottle of milk, juice or soda pop, Shepard says. Constant exposure to the sugars in any of those liquids can wreak havoc on young teeth, which are much softer than permanent teeth and can abscess in just three or four months. So common is the resulting rot that it has a medical name: "baby bottle tooth decay." But babies who breast-feed are not immune. The phenomenon is particularly noticeable in children who sleep with their mothers and nurse on demand all night long.

Neglecting brushing Meals for low-income kids are often not as healthy as they should be, Shepard says. In fact, the very concept of a "mealtime" may not exist. "With a lot of our families, there isn't even an eating table, so the kids kind of graze through the day," she says. "They get their own snacks. Quite often the dinners are the fast food meals." If you're sharing an apartment with several other people, there may be only a small table with two chairs, she says. Then there's the issue of hygiene: Many parents simply don't brush their children's teeth -- reasoning that the baby teeth are destined to fall out eventually, so why worry about them? And poverty has a way of disrupting even the best of intentions in the most conscientious of parents, Shepard says. "There are so many things happening in your life that take precedence over (teeth)," she says. "Violence in the home or being evicted or money issues, and (dental care) just doesn't get top priority." As if they didn't already have enough strikes against them, many poor children in Humboldt County also lack access to what the national Centers for Disease Control deemed one of the 10 greatest public health achievements of the 20th century: fluoridated water. Fluoridated water reduces decay by 30 to 60 percent in baby teeth and 20 to 40 percent in adult teeth, according to the American Dental Association and the Centers for Disease Control. But only 30 percent of California families, and 35 percent of Humboldt County residents, have fluoridated water, according to a 2001 report by the county's Public Health department. The cities of Arcata, Eureka, Scotia and Hoopa are covered. But the rest, including McKinleyville, Garberville, Rio Dell and unincorporated parts of Eureka such as Cutten, are not. A state law passed in 1995 mandated the fluoridation of water in communities of at least 10,000 residents, but the anti-fluoridation torch has been taken up by a growing number of vocal opponents. Cost is not the issue: The average annual price to fluoridate water is about 54 cents per person. What has stopped a number of communities, including Willow Creek, is fear. In the fall of 2000, the Willow Creek Community Services District board decided not to add fluoride to the town's water supply after a number of residents raised questions about its safety (see the Journal, Oct. 26, 2000). Rumors about fluoride's potentially dangerous effects on the body ran rampant. Tom Lewis, the Willow Creek dentist, was on the losing side of the battle. He told the Journal at the time that the anti-fluoride forces were spreading the same "misinformation that's been put out for many years," and that many, many studies had documented its safety. One man went so far as to tell a board member that "the Germans invented water fluoridation to kill the Jews," Lewis says.

Taking action While efforts to increase fluoridation have failed, the urgency of the dental crisis -- so many children in need, so few dentists to see them -- has spurred other action on the part of county officials, nonprofit administrators and educators. The Open Door Community Health Centers has turned a former bank building in Burre Center in Eureka into a $900,000, state-of-the-art dental clinic, due to open in September. It has room for three dentists to treat both children and adults. "It should begin to put a dent in the unmet need," says Spetzler, the Open Door director. But the change may not be apparent right away. Two dentists slated to work at the new clinic will be transferred from Open Door's other Eureka clinic, where the dental office will be phased out, Spetzler says. A third has been recruited, and Open Door is looking for a fourth to staff the mobile van. (Contrary to recent press reports, the state budget impasse will not force Open Door clinics to close, officials say.) Another weapon against decay was deployed this past spring, when McEwen, the county's oral health coordinator, organized a two-month effort to screen 710 children from four Eureka-area elementary schools and apply sealants to those teeth that were still healthy. When brushed onto a child's permanent back molars, dental sealants, a type of enamel bonding, can virtually eliminate the potential for cavities on the biting surface of those teeth. Other sealant clinics are planned. Some local projects aimed at fighting the dental crisis just got a much-needed boost in the form of an $878,000 grant from the California Endowment, a foundation created when California Blue Cross went private. The grant will pay for another sealant clinic and provide money for the new Open Door dental clinic, the Open Door dental van, a visit from the Delta Dental "toothmobile," educational projects and the St. Joseph hospital dentistry program. Those projects are also supported by funding from the Humboldt Area Foundation, the California Conservation Corps, St. Joseph Hospital and the Union Labor Health Foundation, among others. What is needed most to stem the dental crisis, most experts say, is education and prevention. "If your parents lost their teeth when they were in their 30s, it presents a norm," McEwen says. "A lot of people don't realize that teeth can last a lifetime, that baby teeth are important, and that dental disease is 100 percent preventable." Right now, oral health is not viewed as an important part of overall health, McEwen continues. That has to change. "What schools would accept their kids coming in with open abscesses on their arms? Yet we're accepting it in their mouths. This is preventable. I want [to push] the idea that we won't accept cavities. [Or] especially children in pain."

Emily Gurnon is a former

staff reporter for the San Francisco

Examiner.

IN THE NEWS | FROM THE PUBLISHER | CALENDAR

Comments? E-mail the Journal: [email protected] © Copyright 2002, North Coast Journal, Inc. |

Humboldt

County is facing a critical shortage of dentists who will care

for low-income children -- children who are much more likely

to have tooth problems than those from more affluent families.

The overwhelming majority of private dentists refuse, as a general

rule, to take Medi-Cal or Healthy Families, insurance for low-income

families not poor enough to qualify for Medi-Cal.

Humboldt

County is facing a critical shortage of dentists who will care

for low-income children -- children who are much more likely

to have tooth problems than those from more affluent families.

The overwhelming majority of private dentists refuse, as a general

rule, to take Medi-Cal or Healthy Families, insurance for low-income

families not poor enough to qualify for Medi-Cal.

The

scope of the dental problem in Humboldt County is not easy to

assess. Dental workers have gathered some information by visiting

schools and other locations throughout the county. For example,

from February to May, the Open Door Community Health Centers

stationed its mobile dental van in Rio Dell and asked parents

for permission to give free exams to their elementary school

children. [photo at left]

The

scope of the dental problem in Humboldt County is not easy to

assess. Dental workers have gathered some information by visiting

schools and other locations throughout the county. For example,

from February to May, the Open Door Community Health Centers

stationed its mobile dental van in Rio Dell and asked parents

for permission to give free exams to their elementary school

children. [photo at left] Part

of the reason there are so few dentists here who will take Medi-Cal

is that there are few dentists, period. Nationally, the dentist-to-population

ratio is declining, according to the Surgeon General's report.

In rural areas like Humboldt County, recruitment of high-level

professionals is a constant challenge, says Herrmann Spetzler,

executive director of the Open Door Community Health Centers,

which run dental clinics in Eureka, Arcata and Crescent City.

[photo at left]

Part

of the reason there are so few dentists here who will take Medi-Cal

is that there are few dentists, period. Nationally, the dentist-to-population

ratio is declining, according to the Surgeon General's report.

In rural areas like Humboldt County, recruitment of high-level

professionals is a constant challenge, says Herrmann Spetzler,

executive director of the Open Door Community Health Centers,

which run dental clinics in Eureka, Arcata and Crescent City.

[photo at left] SIX YEARS

AGO, TOM LEWIS was running a thriving dental business in Arcata.

But after 26 years of private practice, first in Oakland, then

here, he'd had enough.

SIX YEARS

AGO, TOM LEWIS was running a thriving dental business in Arcata.

But after 26 years of private practice, first in Oakland, then

here, he'd had enough.