|

by GEORGE RINGWALD FIRST OF TWO PARTS SAM STANSON'S FIRST JOB IN HUMBOLDT COUNTY -- HE WAS LATER to fight a losing battle for Eureka's historic Vance Hotel -- was selling real estate for Shelter Cove. He now lives in Southern California, slowed down by multiple sclerosis. "They flew us up [from San Diego] to look at the property, " he recalls. "The place was a ghost trail. It was all sold in Southern California. They didn't sell it up here. Nobody's that dumb." Never one to mince words, Stanson, in a recent telephone conversation, went on to say: "All of the ocean lots were sold the year before. The rest of the place was so steep the lots were worthless. A con job." "Yeah, it probably was," agrees Don Raffaelli, although he usually fixes the blame on "the blue suede shoe boys from Los Angeles." As a longtime employee of the county's Public Works Department, from 1957 to 1998, Raffaelli was well-acquainted with Shelter Cove problems. "The developers [variously named companies throughout the cove's history] had all sorts of design problems. They missed a lot of drainage area. And they had culverts in the wrong areas. These guys were ripping off the investors. They were pushing those lots sight unseen." Poster child

When voters in 1972 approved Proposition 20 -- the Coastal Initiative -- which established the California Coastal Commission and imposed unprecedented controls on coastal development, it was in no small part because of high-profile projects such as Shelter Cove. Shelter Cove, along with Sea Ranch in Sonoma County and Pacific Shores in Del Norte County, were "cited by campaigners for Proposition 20 as examples of why the state needed a coastal act," said Bob Merrill, manager of the North Coast District of the Coastal Commission. "If the Coastal Act [which passed in 1976 and made the permitting powers of the Coastal Commission a permanent fact of life in California] had been in place at the time Shelter Cove was proposed, [the project] probably wouldn't have happened," Merrill said. In addition to spurring more stringent protections of the coast, the Shelter Cove debacle also resulted in a toughening of California's real estate disclosure laws. "We all hate regulations and government involvement in things, but projects like this one are the reason laws get more strict and complex," said Guy Kulstad, former public works director for Humboldt County. Unbuildable lots Kulstad played a key role in forcing Shelter Cove's developers to rectify the subdivision's shortcomings. But there was a limit to what could be done. Raffaelli, for example, recalls that rain storms in the mid-sixties "wiped out access to a lot of lots. There were about 4,500 lots when the subdivision started, and it was down to about 3,400 after the storms." Stephen A. Strawn, in office now for a little over 30 years as treasurer and tax collector of Humboldt County, estimates that about 15 percent of the lots at Shelter Cove are unbuildable. He says that the early-day engineers "didn't always take topography into account." As a result, he adds: "Many of the properties that are adjacent to the ocean are on little or no land, because of the slippage, the erosion over the years. The other thing that often occurs in some of these areas is that these parcels are on an embankment that goes straight up, 20 feet in the air, and I'm not exaggerating." "There are hundreds of stories on Shelter Cove," Strawn goes on. "What I personally have found as I go amongst all of these properties and offer them for sale, the majority of them are not on a valid building site. Even if you have a lot that fortunately is flat, the size of the lot will, almost always, not percolate for a septic system." Under the law, Strawn is obligated to offer lots for sale, at annual auctions, whenever the taxes have not been paid for over five years. "Now I can tell you," he adds, "that as long as I've been in office, some of these properties I have sold two and three times." At a public auction in June, 135 Shelter Cove parcels were put up for bid because their owners had been delinquent with their property taxes. According to Sara Beccaria at the county tax collector's office, 128 of the parcels sold, at prices ranging from $1,400 to $17,000. Why weren't property taxes paid on these lots? Largely because they are difficult, if not impossible, to build on. Strawn has an assortment of sad letters from property owners who have found they're saddled with unbuildable lots. One man from Texas writes that he no longer has any interest in owning a lot that is not buildable, and says taxes "coupled with the annual $500-$600 fee for clearing the brush away is simply too much." The Texan closes with the saddest part: "I am very disappointed in the folks that sold the useless lots to me in 1971. My dream has always been to retire there in 2003." Strawn tells also of a Filipino woman who "paid a horrendous amount" ($6,000) for a lot that was unbuildable, and then couldn't get her money back. "She would cry and cry," he says.

Maintenance woes The nearly 400 customers of the Shelter Cove Resort Improvement District who have water, sewer and electric services don't have to contend with the problem of not being on buildable lots. Last year there were 25 new connections to the services, according to RID's general manager, Richard Culp [photo below left] . The district gets telephone service through Verizon, and the electric power poles are maintained nearly to the Whitethorn Post Office up the road toward Redway and Highway 101. The district functions much like a city council, with five elected directors, besides Culp and office staff. Besides keeping the utilities in service, the district also manages the Cove's nine-hole golf course and the airport runway. It has a volunteer fire department under its aegis, but the only police service comes from the sheriff's deputies in Garberville. "We don't have a whole lot of problems," says Culp, "but every once in a while we'll have vandals and yahoos tearing things up." Before coming to Shelter Cove a year ago, Culp, 42, resided in Trinidad. He has worked at Humboldt State University, where he oversaw an infrastructure improvement project, and in Eureka as a civil engineer. He does have a gripe about Shelter Cover: the roads. "There are 40 miles of asphalt roads in Shelter Cove," said Culp, "and the Humboldt County Public Works Department is responsible for maintaining every bit of it. And as you drive around, you'll see that they're having a hard time keeping up in many areas. It's understandable. Look at the drainage problems. That's one of the issues down here, getting the county to maintain these roads when they have a limited budget." Mary Ann Machi, born in Garberville in 1952 and raised in Shelter Cove, is among the descendants of the early-day Machi clan, whose ancestry goes back to a town on the island of Sicily. The Machis settled in Shelter Cove in the 1930s. They are memorialized by a Machi Road in Shelter Cove. "I've been back and forth to Shelter Cove my whole life, but most recently moved to Eureka about four years ago," Machi tells me.

"The stories I've heard is that people who bought that property just wanted to make money," she says, "and they divided it into as many parcels as they could. I've heard stories that a lot of the workmanship was really shoddy. Things like they put in 6-inch culverts when they needed to have 3-footers. "We heard stories that they'd bring people in and tour them around, generating all this excitement, all these lots for sale," she goes on. "They sold lots sight unseen. They sold a tremendous amount of lots to people who were overseas in the military or in Hawaii. They promoted with fancy pictures, not showing that the property was straight up and down. "A lot of people have had a lifelong dream of retiring to Shelter Cove, and they get here and find out they can't build anything." County complicit? Machi then started speculating about the role of local officials. "We were told way back when that the main reason that whole development went through was because the county saw the opportunity to collect property tax on 4,200-plus or minus parcels instead of one big chunk of land that was a big agricultural property they didn't get much out of. So, you know, I think the wheels kind of got greased." I voiced that question myself in an interview with Strawn. How could the county allow all this apparent skullduggery? "I honestly can't answer that," Strawn replied. "I was not here then. The speculation would be that they [the county's supervisors of that day] were likely very pleased that there was going to be this wonderful development. And I would speculate that they were brought into this wonderful vision that these people had of all the color photographs and the benefits to the economy of the county, and of the great vacation resort area, and all of the taxes that would accrue. And somehow, along the line, everyone in the county [government] completely overlooked the fact that much of the land was not buildable." Raffaelli voices a similar supposition. "In those days," he said, "there was a lot of pressure on the board [of Supervisors] from the Southern Humboldt community. They wanted to see this subdivision go through; they anticipated a large influx of people. The Southern Humboldt School District was very supportive of it. There were lots set aside for schools [in the subdivision]. It wasn't just an off-the-cuff, `Here come the blue suede shoe boys selling us a bunch of goods.'" The blue suede shoe boys apparently didn't forget to spread the applesauce for the county's minions -- the streets are named after some of them. Raffaelli notes that there's a Shaller Road, after then-Public Works Director Charles Shaller; a Lindley Loop, after Supervisor Elwyn Lindley; and a Higgins Court, named for then-Planning Director Harvey Higgins. (Shaller, it turns out, left the county to work for the engineering firm for the Shelter Cove project.) That's not to suggest that there weren't conflicts between the developers and the county. In 1970, a mere four years after ground was broken on the project, the county estimated that $1.9 million would be necessary to right deficiencies in the subdivision's roads, drains and related road construction. That estimate came after a Grand Jury criticized the county's original approval of the project and recommended that Shelter Cove's developers be held accountable. The Shelter Cove Co., the developer at the time (subsequent developers included Shelter Cove Sea Park, Ltd., and Old Holdings, based in Massachusetts), ended up paying the county $580,000 in a settlement agreement. That the county got that much was not a small accomplishment. Kulstad, the former public works director, related a tale that gives a sense of the political force that Shelter Cove's developers -- who included a promiment Southern Californian named R.J. Beaumont -- could bring to bear. "Pat Brown [as in former Gov. Edmund G. "Pat" Brown] called me up one day and suggested I was being too hard on them. I suggested he come out and look at the project." Roller-coaster road A gimmick that worked in the developers' favor was that they were flying people into Shelter Cove, and those prospective buyers never saw the road they'd have to travel if they came in by car or truck. "The road was initially a one-lane dirt road," Machi points out. Certainly the road from Redway to Shelter Cove is as scary as they get. It's one hellacious winding road, with more curves than Marilyn Monroe. Not to mention its share of potholes. "Shelter Cove," Machi reminds, "is a destination; it's not some place you pass along the way. You have to be going there, and that turns a lot of people off. I've had people come into the General Store and turn around and go back. They wouldn't drive an inch further. They were just petrified of that road -- even now." Indeed, there is a road sign noting that three RVs have crashed along the way. "A lot of people don't know how to use the low gear, so they put it in drive and ride their brakes all they way down, and by the time they get to the bottom -- if they do -- they have no brakes left."

"There at Whitethorn where the post office is now, we had like an old plank railroad bridge that went over the Mattole River. And when we first went out there, the road was one-way with pullouts. And when you crossed the bridge, there was one curve: The sign said, `Honk before you go around from here.'" She laughs at the memory. Aldridge, originally from Carlsbad, N.M., started working at Shelter Cove in 1969. Her husband, John, had been working in the cove since 1956. Of the Shelter Cove subdivision, she says: "This terrain is so steep they really did a disservice by building those lots so small. The lots down around the airport should have been at least twice the size they are -- 50 by 100 -- and in the septic area they're a third of an acre, and sometimes that isn't enough to accommodate a house and a septic system. "They were building on lots that went straight up the hill, " she said. "And a lot of these people didn't know what they bought. Even today I have on my e-mail right now a message from a guy, says he bought a lot on Cedar Road and it's lot No. 50, right on Telegraph Creek, and that's our water supply. They're no more going to let that guy have a septic permit there than he can fly to the moon, because it's not going to be buildable." Selling on the Internet Aldridge has her real estate license with Linda Yates, in her Lost Coast Properties office next to the General Store. She says of current action on the Internet: "They're selling lots that are not buildable. Who's gonna stop them? There's always some con artists around, you know." Linda Yates says there are a lot of disgruntled buyers of Shelter Cove properties -- people who were misled, and a lot of that problem is perpetuated by the Internet. "To this day, I still have people who have owned their lot since the beginning, but they do not know they have an unbuildable lot. And [sometimes] they've passed away and their children have inherited the lot. And this comes as a shock, because they've been paying taxes for 37 years or whatever. I had one lady come in here from Hawaii. They had three lots, paying on them forever. And all three of them were not buildable. She just broke down and cried. The bottom line is `Buyer, beware!'" Similar advice comes from real estate broker Gene A. Persall, who has lived in Shelter Cove since 1989, having moved up from Yucca Valley in the Southern California desert. "So many of the lots here aren't usable properties, and occasionally someone will come into the office from out of the area and say that they bought a lot on eBay. And I'll say: `You didn't!' And they say, `Yes, I did, and it's on this street.'" And Persall knows where the lot is -- on some hill -- and has to tell this prospective customer: "You'll probably never be able to use it." He goes on: "You should be diligent when you go buy property. It's all up to the broker, but it's some of your responsibility too to be sure you're not having the wool pulled over your eyes. That's what we're here for. Before I close an escrow and sometimes before we enter escrow, we like to have an engineer, a geologist, the county, the local Resort Improvement District employees -- [anyone] we can to give us knowledge on that property. Because there are so many properties here that are still a scam. It's a sad situation, but, like I said, people need to be diligent." Lasting legacy Aldridge, who recently turned 78, hasn't been going down to Shelter Cove quite as often now, after having had a pacemaker installed last year. A member of the board of the Shelter Cove Property Owners Association, she attributes the problems the subdivision has had over the years more to incompetence than anything else. "I don't think it was a scam. I do think there should have been a great deal more planning by the developers." As for the present, she doesn't think much of the county's practice of making delinquent Shelter Cove lots available at public auctions. "All anyone is buying is the privilege to pay taxes. You can't build" on those properties, she says. "It makes me sad that the county does that," she adds.

NEXT WEEK: The Coastal Commission's fight with Shelter Cove. In 1968, as a reporter for the Riverside Press-Enterprise, George Ringwald won a Pulitzer Prize for Meritorious Service. In a series of investigative pieces, Ringwald documented abuses by the judicial system in its management of properties belonging to the Agua Caliente Indian tribe near Palm Springs. Editor Keith Easthouse contributed to this report.

Comments? © Copyright 2003, North Coast Journal, Inc. |

Begun

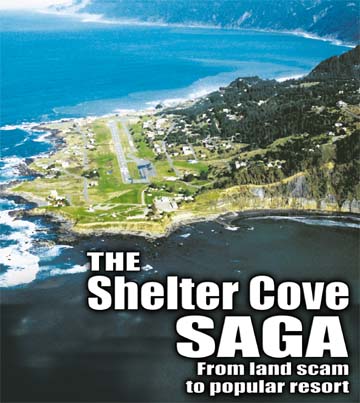

in 1966, the 2,500-acre, 4,000-plus-home subdivision was the

single biggest residential development in the state at the time.

Its location directly along a magnificent and remote stretch

of coast about 100 miles south of Eureka, along with the fact

that the project was dogged from the start by design problems,

made it a poster child for those who wanted to protect California's

shoreline from reckless development.

Begun

in 1966, the 2,500-acre, 4,000-plus-home subdivision was the

single biggest residential development in the state at the time.

Its location directly along a magnificent and remote stretch

of coast about 100 miles south of Eureka, along with the fact

that the project was dogged from the start by design problems,

made it a poster child for those who wanted to protect California's

shoreline from reckless development.

Of

course she knows about the Cove's problems in the early days.

Of

course she knows about the Cove's problems in the early days. The

other day I met with Frances Aldridge [photo at right]

at her classy mobile home in Fortuna, and she recalled the road

from Redway to Shelter Cove as being "a lot more crooked"

when she first took that drive to Shelter Cove back in 1969.

(Which I find hard to believe.)

The

other day I met with Frances Aldridge [photo at right]

at her classy mobile home in Fortuna, and she recalled the road

from Redway to Shelter Cove as being "a lot more crooked"

when she first took that drive to Shelter Cove back in 1969.

(Which I find hard to believe.)