|

IN

THE NEWS | OPINION

| CALENDAR

by KEITH EASTHOUSE

"Whiskey's

for drinking; water's for fighting."

-- MARK TWAIN

THE SPRING CHINOOK LAY BELLY-UP

IN SHALLOW WATER, bobbing up and down rhythmically as if the

Trinity River had rocked it gently

to sleep. But this, clearly, was not sleep.

"It was coming back up

the river. It would have spawned in September," said Mike

Orcutt, senior fisheries biologist with the Hoopa Valley Tribe. [photo below right]

Looking down at the silver-white

fish on a sunny July morning, the water appeared clear as glass.

But looking out at the river itself, the water, through the trick

of light refraction, appeared blue-green. It looked almost tropical.

Orcutt and his two passengers

piled into a steel-hulled boat and moved out into the current.

Within minutes the craft scraped bottom. The harsh grating sound

surprised a flock of turkey vultures that had been feeding on

something on the bank -- another dead salmon?

Orcutt

said he first heard reports of dead fish in the river a few weeks

before. "It happened last year, too," Orcutt said,

adding that it's not clear what's killing them. Rising water

temperatures, always a problem in the summer, may be making them

more prone to disease or parasites. Orcutt said it's possible

nothing out of the ordinary is going on, that the "pre-spawning

mortality," as he put it, is simply more noticeable because

the salmon run this spring was sizeable. Orcutt

said he first heard reports of dead fish in the river a few weeks

before. "It happened last year, too," Orcutt said,

adding that it's not clear what's killing them. Rising water

temperatures, always a problem in the summer, may be making them

more prone to disease or parasites. Orcutt said it's possible

nothing out of the ordinary is going on, that the "pre-spawning

mortality," as he put it, is simply more noticeable because

the salmon run this spring was sizeable.

"The typical [mortality]

level might be 1 percent per year, so if the run is big you're

going to see more dead fish."

Might salmon be dying because

large portions of the river's flows are dammed and diverted southward,

to farmers in the Central Valley? In other words, isn't the river

lower -- and therefore warmer -- than it would be at this point

in the summer if no diversions were taking place? Orcutt doesn't

answer the question directly, perhaps because he knows that flows

on the unregulated Trinity varied widely and could drop to a

trickle from late July through the end of September.

But he does say this: "We've

created an artificial system here that may be making the fish

more vulnerable."

A

pivotal hearing

The artificial system of the

Trinity River, and to what extent it should be restored to its

natural state, has been under debate for more than two decades

-- and there is no resolution in sight.

"I don't foresee an end

to this in the near future," said Tom Stokely, a planner

with Trinity County and a key player in efforts to restore the

river. "I'm 47 and I expect to be working on this until

I retire."

The latest chapter of the Trinity

saga will unfold in a federal courtroom in Fresno next Tuesday,

when U.S. District Court Judge Oliver Wanger hears arguments

in a case that is widely viewed as pivotal to the future of the

Trinity River. At issue is a lawsuit filed in late December 2000,

just days after then-Interior Secretary Bruce Babbitt signed

a years-in-the-making restoration plan for the Trinity.

More water for the Trinity lay

at the heart of the plan. Babbitt ordered that no more than 52

percent of the river's water could go to the Central Valley --

a significant drop from the 75 percent that had been diverted

for much of the 1980s and 1990s, and a sea-change from the 1960s

and 1970s, when up to 90 percent of the Trinity was sent south

every year.

Not surprisingly, farmers fought Babbitt's order.

Westlands Water District, which has used Trinity River water

to develop a multibillion-dollar agricultural economy, filed

a legal challenge. It was later joined by the Sacramento Municipal

Utility District (SMUD), which stands to lose as much as $2 million

in electricity generated by Trinity powerhouses. Not surprisingly, farmers fought Babbitt's order.

Westlands Water District, which has used Trinity River water

to develop a multibillion-dollar agricultural economy, filed

a legal challenge. It was later joined by the Sacramento Municipal

Utility District (SMUD), which stands to lose as much as $2 million

in electricity generated by Trinity powerhouses.

Last year, Wanger, who has a

reputation for favoring agricultural interests, applied the brakes

to Babbitt's "record of decision." He said the Interior

Department didn't look closely enough at how the plan might affect

power generation. He also said the department didn't properly

study how keeping more water in the Trinity might affect imperiled

fish species in the San Francisco Bay Delta.

Wanger ordered the government

to fix these shortcomings. He allowed parts of Babbitt's plan

to go forward -- such as projects to restore fish habitat and

raise bridges downstream of Lewiston Dam to make way for higher

flows. But he postponed a decision on the higher flows themselves,

without which, many believe, much of the rest of the plan cannot

work.

It is the issue of the flows

-- whether to give the Trinity more water now, as called for

in the Babbitt plan, or to study the matter further, as farming

and power interests are demanding -- that Wanger is expected

to rule on, either at next week's hearing or shortly thereafter.

Wanger has already made one

decision this year regarding flow levels in the Trinity.

Because last year was a drought

year, he had capped the flows allotted to the Trinity at 368,000

acre-feet -- the amount allowed in a "critically dry water

year" under the Babbitt plan and slightly more than the

minimum the river was getting prior to the plan. Last year's

limit would have remained in place this year, even though this

was a normal year in terms of precipitation, were it not for

the Hoopa tribe, which petitioned Wanger to give the Trinity

the amount called for in Babbitt's plan in a "normal water

year" -- 647,000 acre-feet of water (an acre-foot is the

amount of water necessary to cover an acre of land in a foot

of water).

Wanger balked at that. But in

a decision at the end of April, he did agree to allow an additional

100,000 acre-feet of water -- 32.5 billion gallons -- to go down

the river this year, bringing the Trinity's 2002 allotment to

468,000 acre-feet.

The Hoopa tribe's victory, if

that's what it was, could be short-lived. SMUD has come forward

with a proposal that, in the view of critics, amounts to a maintenance

of the pre-record of decision status quo -- significantly lower

flows than called for by Babbitt and restoration projects that

rely heavily on mechanical methods, such as dredging, to improve

fish habitat.

Arlen Orchard, an attorney with

SMUD, said Babbitt's plan is based on flawed science. "There

are other [proposals] out there that provide a more balanced

approach that will result in increased flows and fish restoration

but at the same time will not have quite as big a detrimental

effect on downstream water users," Orchard said in a recent

telephone interview from his Sacramento office.

Stokely of Trinity County, who

was heavily involved in developing the planning documents that

support the Babbitt plan, said the SMUD approach has already

been studied. "It didn't cut the mustard," Stokely

said.

False

assurances

The Trinity River controversy

dates back to the early 1950s, when a string of public hearings

was held regarding a government plan to dam the river and send

some of its water over the mountains and down into the Sacramento

Valley. Irrigators supported the proposal, as did hydropower

interests. Concerns were raised about the impact on the river's

salmon and steelhead fishery. But then-Congressman Clair Engle,

who was on the verge of making a successful run for the U.S.

Senate and needed the support of California's powerful agriculture

industry, assured voters in the north that "the Trinity

project does not contemplate diversion of one bucketful of water

which is necessary in this (the Trinity) watershed."

An official with the U.S. Bureau

of Reclamation, the agency that would build the dams that would

make the diversion possible, went so far as to claim that the

"fisheries would be improved" by the project.

The 1955 legislation that created

the "Trinity River Division" of the Central Valley

Project, a vast water collection and power generating network

that to this day is critical to the state's farming and energy

interests, directed the Interior secretary "to adopt appropriate

measures to ensure the preservation and propagation of fish and

wildlife."

The next year, the reclamation

bureau told Congress that no more than 56 percent of the Trinity's

water would be diverted to the Central Valley Project.

Seven years later, in 1963,

after the completion of Trinity and Lewiston dams and of the

Clear Creek diversion tunnel, which funnels Trinity River water

into a reservoir near Redding, these assurances were revealed

to be nothing more than empty words. The reclamation bureau,

which had just signed a water-delivery contract with the Westlands

Water District in the San Joaquin Valley, promptly began diverting

90 percent of the river's water and continued to do so until

the early 1980s.

By the late 1960s it was becoming

clear that fish populations were in serious decline. By 1977

so much water was being sent to irrigators that Trinity Lake,

the reservoir formed by Trinity Dam, was drained to 10 percent

of its capacity. "They hardly let water out of the dam"

and into the river, recalled Stokely. "It was an extreme

[water] temperature emergency. Thousands of fish were dying.

It was a catastrophe."

Showing

that fish need water

How was the reclamation bureau

able to send so much water to the Central Valley and leave so

little for the Trinity basin -- particularly since Congress had

instructed the executive branch to protect the basin's fish populations?

According to Tom Schlosser,

a lawyer representing the Hoopa tribe, the answer lies in the

language of those instructions. Despite all the assurances, in

congressional proceedings and from politicians, that the Trinity

and its fish populations would not be deprived, the 1955 act

gave the bureau a virtual free hand in two ways: It allowed the

agency to release as little as 150 cubic feet of water per second

to the river ("a trickle," according to Schlosser);

and it qualified its requirement that the fishery be protected

by directing the Interior secretary to take only "appropriate

measures."

Schlosser said this put "on

the fisheries agencies and the tribes the burden of showing what's

needed to protect the fish."

"The Bureau of Rec's view,"

Schlosser continued, "was that all we have to do is the

minimum -- 150 cfs -- until you show us something else is appropriate.

To go above [that] one had to show the fish needed water."

Schlosser said "it took

a few years" for scientists from the California Fish and

Game Department and the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service to do

just that -- "and [it] took decades for the bureau to comply"

and start releasing more water to the river.

Byron Leydecker, founder of

the group Friends of Trinity River and a vocal critic of the

diversion project, said that the 90/10 diversion ratio "happened

in my opinion because the bureau doesn't pay any attention to

the law." He also noted that no one at the time sued.

That last point jibes with something

that Floyd Dominy, a retired reclamation bureau commissioner

who spearheaded the Trinity project, told the Sacramento Bee

in a recent interview. "Back in our day, we didn't have

the naysayers," said Dominy, now 92. "We didn't have

this Endangered Species Act. Everybody thought the projects were

beneficial and in the national interest."

Challenging

the bureau

Trinity County was one of the

first naysayers, taking the reclamation bureau to court in the

late 1970s after the near draining of Trinity Lake and the fish

debacle.

Another

was the Hoopa tribe, which became incensed after Indian fishermen

were blamed for the crashing fish populations. And not just blamed.

"The Indian fishermen who continued to exert their right

to fish got pounded into the sand and were arrested by federal

marshals," recalled Clifford Lyle Marshall, chairman of

the Hoopa Valley Tribal Council [photo

at left]. A subsequent, three-year

government study found that Indian fishing was having a minimal

impact and identified three reasons for the disappearance of

the fish: the diversion of water from the dams, erosion from

logging and overfishing in the ocean. "We were exonerated

in three years," Marshall said. "That was the first

battle. After that, we decided we wouldn't get caught again without

our own science." Another

was the Hoopa tribe, which became incensed after Indian fishermen

were blamed for the crashing fish populations. And not just blamed.

"The Indian fishermen who continued to exert their right

to fish got pounded into the sand and were arrested by federal

marshals," recalled Clifford Lyle Marshall, chairman of

the Hoopa Valley Tribal Council [photo

at left]. A subsequent, three-year

government study found that Indian fishing was having a minimal

impact and identified three reasons for the disappearance of

the fish: the diversion of water from the dams, erosion from

logging and overfishing in the ocean. "We were exonerated

in three years," Marshall said. "That was the first

battle. After that, we decided we wouldn't get caught again without

our own science."

The county and the Hoopa tribe,

along with the Yurok Tribe, which has land northwest of the Hoopa

reservation, were instrumental in persuading Cecil Andrus, Interior

secretary under President Carter, to order, in 1981, that a 12-year

"flow study" be undertaken to determine how much water

would be needed to rejuvenate the fisheries. The county and the

tribes also played a critical role in pushing Congress to pass,

in 1984, legislation that mandated "restoration of fish

and wildlife populations levels to those which existed immediately

preceding construction of the Trinity Division."

The problem back then, and to

this day, was that there never was enough water given to the

Trinity to accomplish the goal of restoring fish populations.

For example, Andrus, in a foreshadowing of Babbitt's plan, directed

that water flowing into the river be increased by varying amounts.

But his mandated flow increases never took place because of emerging

drought conditions.

Flows were finally increased

in 1991, when Interior Secretary Manuel Lujan, in response to

a petition from the Hoopa tribe, ordered that the minimum flows

in the river be increased to 340,000 acre-feet.

The next year, the 1992 Central

Valley Project Improvement Act ordered the Interior secretary

to determine by the end of 1996 the flows required to restore

the river. Babbitt missed this deadline, finally meeting it four

years later at the tail end of the Clinton administration.

Failed

restoration

In the 1980s, a new phase began

in the Trinity fight, one that centered on projects to restore

the river's fish populations. To understand these projects, it

is first necessary to understand the extent to which the Trinity,

which once offered superb spawning and rearing habitat, had become

inhospitable to fish.

First and foremost, the two

dams completely blocked access to the best the river had to offer

-- over 100 miles of cold water salmon and steelhead habitat

above the two dams. That forced the lower river, in particular

the 40-mile stretch below Lewiston Dam, to take on the role of

providing salmon and steelhead with the habitat they need to

grow when they are young and spawn when they reach the end of

their life cycle.

It was originally thought that

the loss of the upper Trinity could be compensated for by installing

a fish hatchery at the Lewiston Dam -- and to some extent this

has been proved true. According to Joe Polos, a fisheries biologist

with the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, the hatchery has been

"integral in sustaining downstream populations. In some

years a majority of the fish spawning in the river are hatchery-produced,"

Polos said.

But while the hatchery has helped

prevent Trinity salmon and steelhead from disappearing altogether,

it has not made possible healthy populations. While there is

not extensive data on predam fish populations, Polos said the

best scientific estimate is that fish populations on the Trinity

today have declined about 90 percent from what they were when

the river was wild.

The reason the hatchery hasn't

had more of an effect is simple -- dumping more fish into the

river didn't address the habitat problem.

The diversion has robbed the

river of the high flows that scour out the channel and form the

cool, deep pools preferred by the fish. iPredam peak flood levels

were as high as 100,000 cubic feet per second. Today, the highest

flows from the Lewiston Dam are on the order of 6,000 cubic feet

per second.

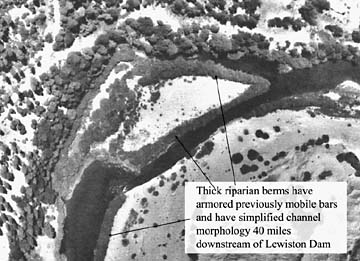

Several things have happened

in the absence of powerful floods, most notably the creation

of what are known as "riparian berms." The natural

Trinity would move back and forth horizontally depending on how

much water was in the river, creating back channels that were

ideal for young fish to hang out in and grow before they move

down the river and into the ocean. When the flows dropped permanently

because of the diversion, those back channels disappeared. Even

worse, willow seedlings and other vegetation that used to get

routinely swept away by high water now had nothing to block their

growth. The river got "channelized," as Scott McBain,

an Arcata-based consultant who is an expert on river restoration,

put it.

Many of the restoration projects

have focused on mechanically removing the vegetation armoring

the banks. According to Leydecker, a vocal critic of the restoration

effort, the majority of the projects failed for a simple reason:

The flows weren't large enough to prevent a new generation of

vegetation from re-establishing itself.

Another type of restoration

work has to do with addressing the fact that many of the gravels

that are ideal for spawning are intercepted by the dams and never

make it to the lower river. The solution has been to dump gravel

at strategic locations. Here again the results have been less

than successful and for the same reason -- not enough water,

in this case to transport the gravel downstream.

Leydecker is concerned that

history is going to repeat itself. Babbitt's plan calls for more

than 40 restoration projects over the next seven to nine years

on the part of the river below the Lewiston Dam. Judge Wanger

has ruled that those projects can go forward. If they do go forward,

but without the flows designated by Babbitt, Leydecker said the

restoration effort will continue to be futile -- and might very

well be harmful. "If they're going to be running tractors

around in there in the absence of water, I'm concerned they're

going to ruin the damn river."

Doug Schleusner, the reclamation

bureau official who is heading up the restoration work, acknowledged

that getting the flows Babbitt called for is important. But he

said that the restoration program will be flexible and will adapt

as needed. "If it turns out the science says we can't reliably

expect the flows to be sufficient, then we wouldn't go that way.

If we do believe we have enough water going down the river, then

maybe this is an opportunity to test our restoration techniques."

Schleusner said that there are

some projects, such as certain "gravel introduction"

efforts, that can "proceed regardless of flows."

McBain said the 12-year flow

study that was initiated in the 1980s has already shown that

the flows the river has been getting aren't sufficient to allow

the restoration work to be successful. He said it's an open question

whether the flows Babbitt outlined will be enough.

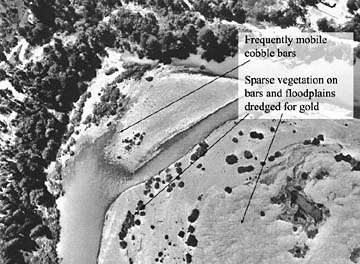

PRE-DAM CHANNEL

POST-DAM CHANNEL

Images courtesy of McBain

& Trush

'An Indian playground' 'An Indian playground'

Like Dominy, the retired reclamation

bureau czar who made the Trinity diversion project possible,

Jimmy Jackson is 92 years old [photo

at left]. But that's probably all

he has in common with Dominy, a man considered by environmentalists

to be an arch-villain for his role in a slew of dam projects

in the 1950s and 1960s -- most notoriously the construction of

Glen Canyon Dam, which drowned an extraordinarily beautiful and

labyrinthine desert canyon in southern Utah.

Jackson, an elder with the Hoopa

tribe, remembers that when he was young there were "fish

all over the damn place" in the Trinity. "There were

a lot of deep holes" for the fish, Jackson said during an

interview at his home on the Hoopa reservation. "Now all

the gravel has piled up and filled all our deep holes."

A lively man with a sharp sense

of humor, Jackson is defiant, not defeated, when he talks of

the river. "`Normal flows,' the white man calls it,"

Jackson said, an edge of scorn in his voice. "They cut us

off and took our water. They killed our fish. That was our food."

The river provided something

else to the tribe, Jackson said: a sense of sacredness that is

still expressed by the numerous ceremonies the tribe holds along

its banks. "It's a wonderful thing, that river. It's an

Indian playground. It's just like a church."

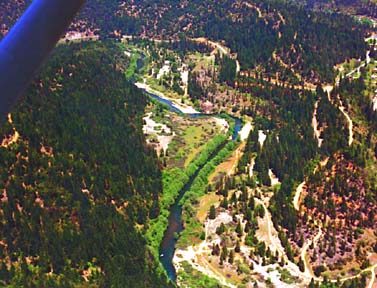

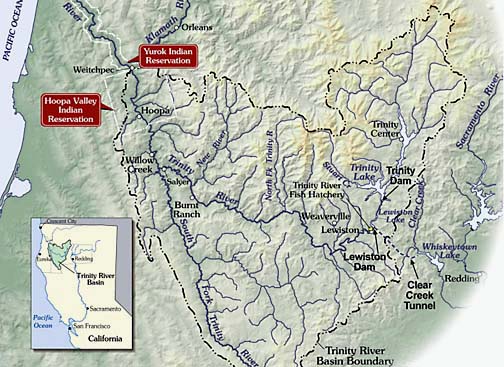

Above: aerial view of the Trinity River

Below: Map of Trinity River overview

Images courtesy of McBain

& Trush

IN

THE NEWS | OPINION | CALENDAR

Comments? E-mail the Journal: ncjour@northcoast.com

© Copyright 2002, North Coast Journal,

Inc.

|