|

by JIM ROSSI

Now, Riggan cuts trees to save homes from wildfire. Along with map specialist Will Harling, he coordinates the Orleans/Somes Bar Fire Safe Council -- putting people to work and reviving the Karuk tribe's fire culture. "My activism," he said recently, "is about getting people to cooperate." [photo at right: Ben Riggan burns slash near a home off Ishi Pishi Road. Photo courtesy of Orleans/Somes Bar FSC] Cooperation is a rare commodity in an area long polarized between environmentalists and loggers. But Riggan, who helps landowners make their properties less flammable, can point to tangible results. Take a 2002 thinning project along the Ishi Pishi -- End of the Trail -- Road. Instead of an incendiary thicket of underbrush, dead branches and leaves, neatly stacked brush piles await controlled burning, shaded by Douglas firs. Most of the region's people live clustered near the Ishi Pishi, surrounded by Six Rivers, Klamath and Trinity national forests as the road winds through a narrow mountain valley from Orleans to Somes Bar, at the remote fringes of Humboldt. With the fire season underway, similar FSCs have geared up in the Lower Mattole, Willow Creek, Southern Humboldt, and around the American West. The goal isn't to prevent fire -- it's for wildfires to burn around communities, instead of through them. The origin of fire safe councils can be traced to the Oakland hills fire of 1991, in which 25 people were killed and more than 3,000 homes, condominiums and apartments destroyed on a hot, windy Sunday in October. That disaster led Bruce Turbeville, a public education officer with the California Department of Forestry, to come up with the idea of forming local entities -- fire safe councils -- to better educate homeowners about ways to protect their properties from wildfire. A series of destructive blazes that broke out a couple of years later in southern California coastal communities like Malibu added impetus to the effort. [photo below left: After thinning, slash piles are burned along Ishi Pishi Road. Photo courtesy of Orleans/Somes Bar FSC]

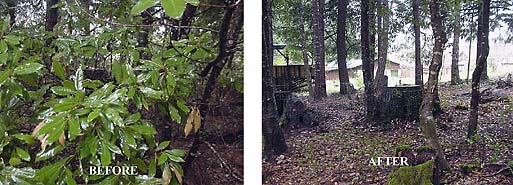

With FSCs, environmentalists and property rights advocates finally found something they could agree on -- protecting communities should be a top priority. Tim Ingalsbee, director of the Western Fire Ecology Center in Eugene, Ore., and a former wildland firefighter, put it this way: "FSCs are the vanguard of a new approach to managing fire in the West." [photos below: Thinning around Ishi Pishi Road -- before and after. Photos courtesy of Orleans/Somes Bar FSC]

Scapegoating environmentalists Experts almost universally agree about community fire protection: The occurrence of wildfire can't be stopped, but damage to homes can be prevented -- by 90 percent or even more. Nonetheless, in one more example of trying to undo Clinton-era land management policies, President Bush's Healthy Forests Initiative cuts funding for community fire protection efforts -- like fire safe councils -- by as much as two-thirds. That's got Riggan and Harling concerned. Of the $380,000 their FSC has received since it came into existence two years ago, $300,000 came from Clinton's National Fire Plan. In essence, the Bush policy blames wildfire damage on bureaucratic red tape and environmentalist lawsuits, and eliminates public oversight of "fuels reduction" projects in the West's vast national forests. Critics say the administration is ignoring wildfire protection and giving the timber industry a blank check to log. "They'll call anything `fuels reduction' to get funding," said Riggan. Even if that's going too far, there's no disputing that fire prevention doesn't pay, while fire fighting does. "Big bucks are made when there are fires," observed Tim McKay of the Northcoast Environmental Center in Arcata. Indeed. There are appropriations to fire agencies; overtime pay to firefighters; contracts with nearby hotels, caterers and transportation businesses (helicopters, for example, typically cost $4,000 per hour). Afterward comes salvage logging, which in addition to being yet another subsidy, is environmentally damaging: Bulldozing roads over fragile, charred soil greatly increases erosion, and too often loggers are allowed to cut unburned trees, including old-growth specimens that have survived repeated wildfires. "Community protection falls down the list as different groups fight over money," McKay added. Shoving the public aside "The forest policy of our government is misguided policy," President Bush declared at a speech near Oregon's Biscuit fire in August 2002, announcing his Healthy Forests Initiative. "It doesn't work." Parts of the plan have already been enacted as rules by the administration. However, the Healthy Forests Restoration Act being debated in the Senate would enshrine it into law (it has already passed the House). According to the White House website, Healthy Forests "exempts timber cutting as part of a fuels treatment project from public notice and comment as well as judicial review and appeals." Healthy Forests essentially nullifies the Endangered Species Act, National Forest Management Act and National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) on any timber project on federal land that is categorized as a "fuels reduction" project. "We'll make sure that people have their voice," said Bush, "but aren't able to tie it all up." Riggan believes the environmental laws in question generally help -- not hinder -- the fire safe councils. "The NEPA process is important," he said. "It gives multiple agencies -- with jurisdiction over everything from air to water -- a chance to have input on a project." NEPA, which also allows citizen input, is required on any FSC project that involves federal funding. The facts support Riggan. According to Congress' General Accounting Office, only 3 percent of fuels reduction projects were appealed over the last two years -- the vast majority went forward without delay. Mike Wood doesn't buy "Healthy Forests" either. As director of the Garberville-based Institute for Sustainable Forestry, Wood works with timber companies, environmentalists and government agencies. "In this time when involvement in government affairs is consistently under attack," he said, "I think we need to at least see the data that supports further restrictions on citizen participation on public lands." And by "streamlining" the NEPA process, said Wood, "Healthy Forests can undercut the middle ground in logging disputes, taking out the incentive to work together." Ingalsbee and a coalition of wildland firefighters have aggressively lobbied against the Healthy Forests Initiative. "We feel it is wrong for the Bush administration to propose cuts in funding for the National Fire Plan," they wrote in a letter to the media, "and then argue for the need to increase timber sales in order to pay for hazardous fuels reduction." The NEC's McKay was more blunt: "They're using people's fear of their house getting burned down to get more access to remote forests." More moderate -- and more authoritative -- voices also object to Bush's approach. Stephen J. Pyne, history professor at Arizona State University and author of several books on fire, said the administration had polarized the wildfire debate. "The issue is how to change the combustibility of landscapes, so we can control the fires we want controlled," he said. "Instead, we went right for the political jugular -- environmental rules versus logging. The present situation is absurd. It's a blood feud." The Karuk way The Karuk were controlling fire long before the federal government even existed. In a yearly ritual around Offield Mountain, near present-day Somes Bar, the tribe rolled flaming logs down the mountainside during a lull in the rainy season. The logs spread low-intensity ground fire through wide swaths of grasses and understory before being extinguished in the creeks below. "Karuk are some of the most practical people I've ever met," said Riggan. A core part of the Orleans/Somes Bar FSC, their input ranges from thinning and burning advice to manpower. "Native people in the Pacific West learned to adapt, understand and accept fire as part of their environment," explained Frank K. Lake, a Ph.D. candidate in fire ecology at Oregon State University and a member of the Karuk tribe. "Areas around villages and seasonal campsites were some of the most intensively fire-managed zones on the landscape." Fire helped grow tanoaks for acorns and hearty weeds for basket making. It became a tool for agriculture, hunting and even warfare. In 1947, California outlawed Native burning practices; not only did fire suppression knock forest ecosystems further out of balance, it excised a central part of Native American culture. But this fact also holds the key to a solution, according to Riggan and Lake: Managing fire would empower the Karuk culture. Unlike most Americans, the Karuk describe wildfire with affection, not fear. "Most of the fires are good," said LaVerne Glaze, another Karuk, "but they don't let them go. For years we've said, `Let it burn.'" The Biscuit and Big Bar fires

In 2002, 7.1 million acres did burn nationwide. Over $1.8 billion was spent on firefighting, over a thousand homes get destroyed and 21 firefighters died. Three huge blowups -- Arizona's Rodeo-Chediski, Colorado's Hayman and the Biscuit -- dominated headlines and TV news around the country. The Biscuit fire started in July 2002 from lightning in the unlogged, roadless Kalmiopsis Wilderness of southwestern Oregon. The original plan was to let it burn -- partly because it was a natural fire burning in remote backcountry, and partly because firefighters were already over-committed to scores of emergencies around the West. Then unusually hot, dry and windy weather -- exacerbated by two consecutive years of drought -- caused a major blowup. Over 100,000 acres ignited in a three-day firestorm that threatened communities. The inferno jumped fuel breaks, logging roads and even the Illinois River. But due to a combination of firefighting, community protection and good luck, the fire blazed around towns, and only four homes burned. [photo at right: Less than 40 percent of the 500,000 acres involved in the Biscuit fire in southern Oregon last summer suffered high tree mortality. Photo by Sam Camp] The Biscuit fire burned in a mosaic -- or "mixed-severity" -- pattern. Of the 500,000 acres that comprised the fire zone -- including nearly 29,000 in California's Six Rivers National Forest near Gasquet -- about 20 percent, or 100,000 acres, suffered a "stand replacement event" in which tree mortality was total. In contrast, roughly 300,000 acres -- or 61 percent of the fire zone -- burned lightly or not at all. In effect, Mother Nature treated most of the Kalmiopsis with a prescribed burn, a low-intensity ground fire that reduced fuels and left the big trees intact. "The Biscuit burned pretty much like fires burned through in the past," said Dominick DellaSala, director of the World Wildlife Fund's Klamath-Siskiyou Project in Eugene, Ore. Not only will the forest be better off in the long-term because of the fire, in most of the Kalmiopsis the forest is already better off. "In many areas," DellaSala said, "we're already seeing quite a green-up of new vegetation." "A mosaic fire pattern fosters diversity -- and that's a good thing," added Wood. In 1999, the Big Bar, or Megram-Onion, fire began after lightning strikes, then blazed through blown-down white firs in Six Rivers National Forest, near the Hoopa Reservation. October rains finally snuffed it -- three months, $120 million and 140,000 acres later. Though Big Bar caused California's first air quality emergency, destroyed valuable timber, and threatened Hoopa, it too burned mainly through roadless, unlogged wilderness. The result: a mosaic where the highest fire intensity took place when hot, dry, windy weather kicked up the wildfire, not to mention the many backburns firefighters had set.

Here too, the forest bounced back quickly. Several slopes in the Trinity Alps plagued by invasive plants burned in the summer of 1999. On a recent hike, LaVerne Glaze of the Karuk tribe found native mountain lilies returning in their place. A model plan With another severe wildfire season looming, a fire safe council summit in Lake Tahoe this past spring featured forester Tracy Katelman of the Lower Mattole Fire Safe Council. Or, more precisely, the summit featured the "fire plan" she designed to reduce the wildfire hazard to communities and property in the Mattole watershed. The plan is viewed as a blueprint for community fire protection because of the extent to which it involves residents. Katelman divided the region into eight "neighborhoods," then held meetings in each of those areas to get people's input. Using residents' knowledge and understanding of the area along with her own expertise and the expertise of others on the council, Katelman was then able to develop detailed projects and prioritize areas most at risk. Three FSC projects are currently underway in the Mattole region, funded by $140,000 in public grants: neighborhood fuels reduction near Wilder Ridge, Panther Gap and the Mattole Valley School and Community Center in Petrolia. The Panther Gap work is being coordinated with fuels reduction projects in Humboldt Redwoods State Park, which is nearby. Katelman said this is a step toward doing something FSCs by and large don't do: carry out fuels reduction projects on public lands. The goal of community protection is simple, according to Katelman. "Get the stuff that burns quick out of the way." She said the following steps could reduce the fire threat to homes:

Do all this, Katelman said, and when wildfire comes, it should burn the forest understory and follow the fuel right out of town. Over in Orleans, meantime, Riggan is leading with the saw. In 2002, the Orleans/ Somes Bar Fire Safe Council cleared and set up fuel breaks over 100 strategic acres straddling the Ishi Pishi, using $154,000 in funding from several state and federal agencies. The council employed 20 seasonal workers at wages from $10 to $16 per hour -- good pay in a region devastated by chronic unemployment -- logged 850 volunteer hours, and held monthly meetings for citizens, environmentalists, and agency representatives to work out details and disputes. For 2003, thinning continues around the Ishi Pishi, involving local loggers trained in environmentally sustainable timber harvest methods. What about prescribed burns? "The National Fire Plan is supposed to lead to the use of fire for forest management," Riggan said. But fire safe councils don't burn because of insurance liability. Instead, they prepare landowners to do it themselves, with help from the state forestry department and the forest service. Unlike the Orleans region, the Lower Mattole is mostly private property -- putting the onus squarely on landowners. Luckily, said Katelman, "The ranching community has been burning for a long time, and they've educated the newcomers." Financially feasible? Can we afford community fire protection? Can we afford to go without it? The problem is, removing small trees, dead wood, and underbrush isn't profitable, said Jerry Partain, a retired forestry professor at Humboldt State University and former head of the California Department of Forestry. "If you don't allow the harvest of medium and large trees," -- greater than six inches in diameter -- "you won't get spacing and you won't get revenue." How can forest thinning be made more financially attractive? One solution is offered by the Healthy Forests Initiative, which calls for a $20 per ton subsidy to encourage thinning of small trees and underbrush. Also needed are portable mills that can process small trees -- those from 8 to 16 inches wide -- into commercial wood at a modest profit. Thinning subsidies and portable mills are a good start, acknowledged Wood of the Institute for Sustainable Forestry. But with the current lumber glut from Canadian imports, he said bigger subsidies or grants are needed. That's basically what Reps. George Miller and Peter DeFazio were after when they introduced a competing bill to Healthy Forests earlier this year. The two Democrats wanted to make available $3.5 billion over five years to reduce fire risk on federal land within a half-mile of communities. The bill would also have provided $500 million to state and local governments, Indian tribes and homeowners in places like Ishi Pishi and the Lower Mattole. Finally, the bill would have offered rural landowners financial incentives to protect their own property -- or pay others to do it, fostering long-term jobs in restoration and Native American forestry. Not surprisingly, given that the Republican-led House usually marches in lockstep with the administration, the bill never had a chance. It got shelved in the Natural Resources Committee and never made it to the House floor for a vote.

The Orleans/Somes Bar Fire Safe Council office occupies the bottom floor of a picturesque mountain cabin where Harling lives with his wife off the Ishi Pishi. A small organic vineyard grows on the property, framed by the steep, lush Marble Mountains. Riggan lives with his family near Orleans, past the end of the road. From Harling's deck, Riggan and Harling point out blackened trunks and groves of vibrant young trees on the mountainsides. They are the markings of wildfires past, continually remaking the landscape. The two men believe that fire safe councils, based on community planning, hard work, and Karuk fire practices, are the best wildfire protection around. They both bet the house on it. [photo at right: Will Harling (L) and Ben Riggan work in their mountainside office. Photo courtesy of Orleans/Somes Bar FSC]

Jim Rossi is a free-lance writer based in Arcata. His last article for the Journal, "Is the water bag proposal a Trojan horse?" was our Feb. 6, 2003 cover story. He can be reached via © Copyright 2003, North Coast Journal, Inc. |

BEN

RIGGAN USED TO BE AN independent logger. After being driven out

of business by big timber companies that could afford to underbid

on jobs, he had a lot of time to think. How could he earn a living

from the forests while protecting his remote mountainside community

from the wildfires that blaze through northern Humboldt County?

BEN

RIGGAN USED TO BE AN independent logger. After being driven out

of business by big timber companies that could afford to underbid

on jobs, he had a lot of time to think. How could he earn a living

from the forests while protecting his remote mountainside community

from the wildfires that blaze through northern Humboldt County? But

councils didn't really start popping up in large numbers until

President Clinton signed the National Fire Plan into law after

2000's disastrous wildfire season; along with firefighting and

fuels reduction projects on public lands, the plan prioritized

and provided funding for reducing the fire threat to the so-called

"wildland-urban interface," the zone within a mile

or so of communities that is largely private property. Today,

according to Turbeville, now director of the California Fire

Safe Council, a statewide group, there are 100 fire safe councils

in the Golden State alone.

But

councils didn't really start popping up in large numbers until

President Clinton signed the National Fire Plan into law after

2000's disastrous wildfire season; along with firefighting and

fuels reduction projects on public lands, the plan prioritized

and provided funding for reducing the fire threat to the so-called

"wildland-urban interface," the zone within a mile

or so of communities that is largely private property. Today,

according to Turbeville, now director of the California Fire

Safe Council, a statewide group, there are 100 fire safe councils

in the Golden State alone.

"By suppressing

fires, we're trying to stave off an inevitable natural process,"

said Mike Wood of the Institute for Sustainable Forestry. "Every

dry acre in the West will burn someday. What areas are we going

to let burn? In remote areas, let fires burn."

"By suppressing

fires, we're trying to stave off an inevitable natural process,"

said Mike Wood of the Institute for Sustainable Forestry. "Every

dry acre in the West will burn someday. What areas are we going

to let burn? In remote areas, let fires burn." "Over

30 percent of the Megram fire acreage was a direct result of

burnouts and backburns," said Christine Ambrose of the Garberville-based

Environmental Protection Information Center. [photo at left: Christine Ambrose near

a thriving Douglas fir marked for "salvage" in Six

Rivers National Forest near Ruth Lake.

"Over

30 percent of the Megram fire acreage was a direct result of

burnouts and backburns," said Christine Ambrose of the Garberville-based

Environmental Protection Information Center. [photo at left: Christine Ambrose near

a thriving Douglas fir marked for "salvage" in Six

Rivers National Forest near Ruth Lake. The

End of the Trail

The

End of the Trail