|

Michael Skweir beats steel drums in more ways than one Story & photos by BOB DORAN

It's the Fourth of July and bands have been playing beneath the flagpole all day. But this group is different. The music is infectious -- fall under the spell of the tropical rhythms and it's hard to sit still. It's also hard to ignore, as the pure, bell-like sound cuts through pretty much everything. People of all ages are drawn to it, transfixed until they are compelled to dance. This is the Pan Dulce Steel Orchestra. Two dozen musicians, mostly female, stand behind rows of shining metal cans mounted on iron stands, drumming on them with rubber-tipped mallets. The instruments, fashioned from discarded oil drums, are called pans or steel drums. Michael Skweir is front and center, playing a chrome-plated pan. As the band -- an orchestra, really -- rips into a Trinidadian calypso tune, he plays part of the lead melody, but a casual listener can't really tell who is playing what. It sounds like one big instrument. Skweir and two other band members up there with him that day, Kate Lang [pictured on the left in photo above right] and John Salazar, are the leaders of Pan Dulce. They are also the co-founders of the Pan Action Network, a school for steel drummers that includes a pan manufacturing facility based in a couple of buildings in Arcata. Skweir, who crafts the pans himself, also works at Humboldt State University's music department maintaining and repairing more traditional musical instruments. Sitting down to talk last week at his workshop next door to an Arcata auto body shop, Skweir was working on some drums that will be on display at the Morris Graves Museum starting this week as part of a show called Instruments of Art of the North Coast.

Discovering the pan A Pennsylvania native, Michael Skweir moved to Arcata in 1976 to attend HSU as a music major. At the time his focus was on classical guitar. "I was kind of an orphan in the department," Skweir, 47, said. "They didn't have a guitar major, so I ended up majoring in violin in order to get a degree." When he graduated -- he received his degree in 1983 -- the music department had no particular interest in steel band music. Skweir had heard jazz pan player Andy Narell of New York City perform and was moderately interested in the instrument, but he said, "I never thought I would have an opportunity to play one, or that I would play in a [steel] band. It didn't even occur to me until Eugene Novotney came to the university." Novotney was hired by HSU in 1986 to teach percussion and brought a Trinidadian pan drum with him. After playing the pan locally as part of an ensemble, Novotney decided to start a steel band. Skweir was one of the first members. "I stopped playing the violin and stopped playing the guitar when I discovered the pan," he said. Dubbed the HSU Calypso Band, the group was an instant hit. "We immediately started adding more instruments, and the band grew bigger and bigger," Skweir recalled.

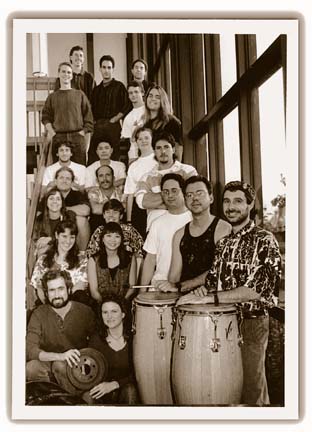

"It excites so many people," he ventured, "both the players and the audience. The sound of a pan draws you in." RIGHT: HSU Calypso Band, late '90s. Founder/Director Eugene Novotney stands next to Skweir at the congas. Howie Kaufmann, holding brake drum at lower left, was the Calypson Band's acting director this year while Novotney was on sabbatical in Africa. Becoming a craftsman Since the music department offered little in the way of support outside of a space for rehearsals, Novotney and Skweir used their own resources to expand the band's collection of pans. While outfitting a steel drum band may not be as expensive as buying instruments for a regular orchestra, well-made pans don't come cheap. (A single drum can cost between $1,000 and $2,500.) Since he already knew how to repair instruments, Skweir decided to learn how to make pans himself. "Eugene referred me to some pan-making workshops. The first was at the University of Akron in Ohio, led by Cliff Alexis, a native Trinidadian. I learned the basic fundamentals of making pans at that one-week workshop." The very next week he went to another workshop in Oregon. "Eugene met me there and we spent a week learning and playing. It was really exciting." Skweir attended several more workshops and learned the finer points of pan construction. Later, Novotney became the coordinator for a series of summer programs held at HSU that brought together percussion students and world-renowned percussionists. The focus was on percussion in general, not just pan, but some of those who attended were adept at both playing and fashioning the instrument. "We had Cliff come out for the workshops and he made some while he was here," said Skweir. "I got to observe and help him. In my opinion, he's one of the best pan makers in the world, so it was quite an honor to work with him." Another gathering of percussionists included Ray Holman, a legendary arranger/composer for Trinidad's steel bands who was delighted by the love of steel drum music he found in Humboldt County. Holman worked closely with the Calypso Band, arranging several of his original compositions for the group and inviting the members to play with his band in Trinidad. In 1994 Novotney, Skweir and two other Humboldt Calypso Band members, Salazar and Mark Rosenthal, took him up on his offer and traveled to Trinidad's capital, Port of Spain, to see the "pan yards" firsthand. "Each neighborhood in Port of Spain has one or two local bands, there might be as many as 40 of them altogether," Skweir said. "Every band has its own pan yard, an area where they have their instruments set up. It's mostly outside; it might be covered. It could be at the end of a dead-end street or in a field, or even right downtown next to an office building. "The pan yard becomes the center of a social area," Skweir went on. "The players are there, then there are people who come to watch, tourists and people from the neighborhood. Food sellers come because there are people there. In the pan yard where we were playing there was even a full bar. It becomes the center of a daily ritual with people learning tunes, others just hanging out." According to David Mangurian, a Trinidadian writer, there are more than 190 steel bands in Trinidad. He also found listings for more than 800 steel bands in dozens of other countries on the Internet, including 240 in the United States, 300 in the United Kingdom, and 130 in Switzerland, where, interestingly, 70 percent of the players are women (in Trinidad, pan players are almost exclusively male). Pan Dulce, of course, is also mostly female. "I think women are somehow more willing to take a chance. We especially get women who are at a stage in their lives where they want to do something for themselves, try something new," said Skweir. The origins of Pan Dulce There came a time when playing with the Calypso Band was not enough for some of the players in the school's steel band. Some had graduated from HSU and wanted to continue playing the music, others just wanted to play more often. In 1999 Skweir joined forces with Salazar, Lang and others to form a small steel combo called Pan Tectonics. They also formed Pan Action Network -- completely separate from the university -- where they began teaching community members to play steel drums. That in turn led to the formation of Pan Dulce. "Almost everyone in Pan Dulce started playing pan with us," said Skweir. "Most of them don't read music -- we teach them the parts by rote, we go over it again and again until they memorize it. That's the way it is in Trinidad; most players learn by rote -- someone teaches them. You learn a little bit at a time, every night you play you might learn 30 seconds worth of music." The music can be quite complex. "In Pan Dulce we have 28 people, and that's a small band compared to the bands in Trinidad, where they often have two or three times that many. How do they all stay together? Well, sometimes they don't -- it is a cacophony at times." While the potential for pandemonium is always present, in concert Pan Dulce sounds like one entity. That's an illusion since in fact it's an orchestra, albeit "an orchestra of like instruments," as Skweir put it. [BELOW LEFT: Pan Dulce Steel Orchestra makes magic at the Humboldt Folklife Festival in Blue Lake, 2002.]

"We play some arrangements by Ray Holman, who comes to the states regularly. And John Salazar deserves a lot of credit. He arranges authentic calypsos or soca tunes [modern "soul-calypso"] that he gets when he goes to Trinidad." Pan Action starts a new class every month. "We have a beginning class, then from there people get into the intermediate class which meets twice a week. Those who are really interested can try to get into Pan Dulce, but that's kind of difficult. You have to play catch-up and learn all the tunes the group is already playing. And if you don't read music, you have to try to learn during rehearsal, while we're playing. It's not easy." Beating out a drum While Skweir is far from a novice when it comes to making steel drums, he's quick to admit that he has a lot to learn. He does it at the Pan Action drum factory, a space with high ceilings behind Wildwood Banjo, just off Samoa Boulevard in Arcata.

"You start with a raw oil drum," he explained. "I get them wherever I can. You sink the top down into a bowl [shape] with a hammer. You beat on it, but with some finesse and some knowledge about where you want to hit and where you don't." He has a pneumatic hammer that he uses along with a small sawed-off sledge to batter the drum into its concave shape. For the finer work he uses various ball peen hammers with their handles cut off so that they don't get in the way when he beats inside the bowl. [photo below right]

After the barrelhead is pounded concave and scored, each note is pounded back so that it's slightly domed. In between stages the drum is heated on a gas burner, tempering the metal, hardening the surface that has become malleable from pounding. Then comes the difficult part: fine-tuning each note. An electronic tuning device with a strobe light shows him when he's sharp or flat, but it's more complicated than that. Each note has high and low components, and each has to work in conjunction with the others in the pan. "Even when the note is in tune with the strobe and it looks good, that's not necessarily the final step. It has to sound good -- and you'll recognize the sound when you hear it. And it has to feel good under your stick -- it has to have the right kind of flexibility and spring." When everything seems just right, a coat of lacquer on the top and bottom is applied to prevent rust; the sides of Skweir's pans are painted by the auto body shop next door. Skweir has made about four dozen instruments so far. They have gone to the Humboldt Calypso Band, to student bands at Freshwater and Sunset schools and to Tina Marier of Orleans, who put together a steel drum band in the hills using a grant from a local cultural organization. Skweir has yet to master building the most complex pan, the tenor. "That's kind of advanced for me at this point," he admitted, displaying a stack of failed attempts that he hasn't had the heart to throw away. "As I continue to make instruments, my quality should continue to improve. I'll try again." And he has somewhat mixed feelings about his inclusion in the Morris Graves Museum's Instruments of Art exhibition. "From the moment I was asked to be part of the show, I told them, I'm not an expert. The truth is, I'm still experimenting, still learning."

Pan Dulce performs Aug. 16 at the Arcata Farmers' Market. Steel on Wheels, the same group but on "human-powered rolling racks," plays at the North Country Fair in Arcata on Sept. 21, 2003, as part of the "All-Species Parade." A small Pan Dulce combo, including Skweir, plays at the Morris Graves Museum Sept. 6 for Arts Alive! Interested in learning how to play the pans? Call 822-PANS. A music of the peopleMICHAEL SKWEIR TRACES THE ORIGIN OF PAN music to "the ghettos of Trinidad where people got together and realized they could pound tones on a piece of metal. With nothing but a few hammers and a barrel, they invented an instrument and started an art form that has grown into a world-wide movement." Of course, all Caribbean music has roots in African rhythms, and the story of the pan begins in the 19th century when Trinidad was still a British colony -- and when most of the people were former African slaves who celebrated holidays like Carnival with wild parades. "Drumming was very popular with the people," said Skweir, "but the British didn't like the noise, so they outlawed hand-drumming. Some say they had some weird idea that people were [planning a revolt and] sending messages with the drums." Whatever the reason, a law was passed in 1883 banning hand drums. Before long the partiers found a new way to make noise. "People turned to bamboo," Skweir said. "It grows wild there. They would cut it to different lengths and stamp it on the ground. Different lengths made different tones and they made complex music." Street parade outfits called tamboo bamboo bands also used biscuit tins and other pieces of metal as additional percussion. The players found that the musical sticks could easily become weapons and musical clashes sometimes turned violent. The result: the British banned tamboo bamboo bands in 1934. BELOW RIGHT: A Brake drum is used as part of the pan orchestra's rhythm section "the engine room."

What happened next is colored by local legend. Two things are certain: during World War II Carnival parades were halted, and by the time the war ended someone had invented a new instrument. One story has it that Winston "Spree" Simon, a youth from Port of Spain, loaned a friend a prized kettle, one with a great tone. The friend basically beat the hell out of it and returned it with the bottom bashed in. While trying to restore the kettle's former tone, Simon pounded the bashed-in part back the other way and in the process discovered that he could create more than one note in the metal surface. After producing a four-tone drum, he experimented further and created a 14-note drum that was a hit at Carnival in 1946. Another account focuses on Elliot "Ellie" Mannette, who started experimenting with 55-gallon oil drums. Discarded by the island's petroleum industry and the U.S. Navy, the drums were typically cut in half and used as trashcans, but Mannette found another purpose for them. While Simon's drums had a puffed out, convex head, Mannette hammered his concave, then pounded the surface back out selectively, eventually perfecting a prototype for the modern pan with two octaves of a diatonic scale. Skweir put it this way, "It's not really certain who invented the pan. I think in truth it was the work of a lot of inventive people." One thing is clear: Like rap, pan music came from the streets. "The early pan yards were not a place where people with any kind of social stature would go; they were home to criminals, or `bad johns' as they are known in Trinidad. But eventually it became the national instrument, and the people of Trinidad are very proud of it." -- reported by Bob Doran Pan magicby EMILY GURNON IT WAS THREE YEARS AGO, A COUPLE OF WEEKS after my daughter was born. I was standing on the Arcata Plaza with her slung in the Baby Bjorn carrier in front of me when I first heard the sound of steel drums. I didn't even know what I was listening to. Maybe it was the sleep deprivation, or the fact that I was still struggling to feel comfortable in Arcata, having moved here from San Francisco only weeks before. But my throat tightened up and I started to cry. The music was so -- how to describe it without sounding sappy? -- magical. "What are those things?" I whispered to the woman standing next to me, pointing to the band that was performing for the Farmers' Market. "They're steel pan drums," she said. I have always loved music. As a kid, I gazed at the pictures in the music encyclopedia we had at home and made a list of the instruments I would learn to play: oboe, French horn, cello, piano. But when it came time to join the school band in fifth grade, it was decided that I would play the clarinet, since the neighbor's family was willing to sell us one for $50. That was what we could afford, so that's what I played. And it was OK. I grew to love the band, if not exactly the instrument, and I was good, though not great, at it. In college, back in Minnesota, I tried to learn piano, dutifully staking out one of the ice-cold music practice rooms each morning at 7:30, playing for an hour, then hurrying off to class. I so wanted to learn, but two years of work netted me little. Reading music that involved more than one note at a time seemed beyond me. So I eventually scratched the other instruments off my list, as well. Adults can't learn to play something new, I decided. You have to start when you're little. But as I stood with my sleeping baby, transfixed by this totally new sound that I was hearing, and happier than I'd been in months, I thought: There must be a way I can get involved in this. How can I do this? Who would teach me? The band, as it turned out, was Pan Tectonics, a professional group led by Michael Skweir, Kate Lang and John Salazar of the Pan Action Network. As if by divine intervention, Lang made an announcement to the crowd in between sets. "You too can play this music!" she said. "New classes start next month! Take a flyer!" I walked home with the little orange square of paper tucked into my back pocket, and showed it to my husband when I walked in the door. "I need to do this," I said. That is how I became an amateur pan player at the age of 40, joining the group that would later become Pan Dulce Steel Orchestra. The thing about the drums is this: Like any art, doing it really well requires a fantastic commitment of time and perseverance, not to mention talent -- something Skweir, Lang and Salazar have in abundance. But doing it well enough to enjoy it? Surprisingly easy. Part of that, according to band member Merry Maloney of Blue Lake, is the way the classes are taught. Students are not required to read music. "They showed us what to do, they showed us on the pan, this is where you put the mallet," she said. Students are shown how to play four bars of a tune, then the next four, and so on. "The most challenging part for me has been the rhythm stuff. But [the instructors] are so patient and they work with us. After a while, it becomes a part of your body and you can play. It's just amazing to me." Maloney, who described herself as "well over 50," said she had no musical background before playing the steel drums. The accessibility of the pans is one reason why Kenzie Mullen got hooked. Mullen, a 53-year-old Trinidad (Humboldt County) librarian, said she first heard the instrument on Sesame Street when she was babysitting her nieces and nephews. "I fell in love with the steel drum then and there," she said. But she had decided long ago that playing music was never going to be part of her life. "I had a terrible sense of rhythm. If a whole crowd was clapping, I would be clapping off everyone else. I thought I didn't have a good musical ear and I thought all musical instruments would be way too hard for me." Now, all that has changed, she said. She joined the group, learned to play, and bought her own set of steel drums. "To feel like I found a passion, something that just thrills me at my age, is such a trip." IN THE NEWS | ART BEAT | PUBLISHER | CALENDAR

Comments? © Copyright 2003, North Coast Journal, Inc. |

![Pan Man [photo of Michael Skweir playing bass pans]](cover0731-photohed.jpg)

BUBBLING,

INTOXICATING MUSIC FILLS THE ARCATA PLAZA, and fills it completely.

BUBBLING,

INTOXICATING MUSIC FILLS THE ARCATA PLAZA, and fills it completely. LEFT: Sarah Cox, Ann

Youmans and Michael Skweir play tenor pans on the Arcata Plaza.

LEFT: Sarah Cox, Ann

Youmans and Michael Skweir play tenor pans on the Arcata Plaza. "What

interested me in pan music was the participatory aspect. You

get to feel like you're part of the group, the same as in an

orchestra or any other group, but there's something different

about it. It's hard to explain what it is.

"What

interested me in pan music was the participatory aspect. You

get to feel like you're part of the group, the same as in an

orchestra or any other group, but there's something different

about it. It's hard to explain what it is. "It's

like a string ensemble or a saxophone quartet -- all the same

instrument, but with a huge range," Skweir said. "In

our group we have five different types of instruments, starting

at the top with the single tenor pan, then going down we have

the double tenor, which would be like the second violins, then

there's the double seconds, which is like the viola; the cello

and bass pans have obvious parallels."

"It's

like a string ensemble or a saxophone quartet -- all the same

instrument, but with a huge range," Skweir said. "In

our group we have five different types of instruments, starting

at the top with the single tenor pan, then going down we have

the double tenor, which would be like the second violins, then

there's the double seconds, which is like the viola; the cello

and bass pans have obvious parallels." In

a recent visit it was full of oil drums in various stages, some

whole, some cut in half; pans-in-progress lay on makeshift tables,

and finished steel drums rested on metal stands. A piece Skweir

has been working on sat atop a drum mounted with part of a car

tire to prevent slippage.

In

a recent visit it was full of oil drums in various stages, some

whole, some cut in half; pans-in-progress lay on makeshift tables,

and finished steel drums rested on metal stands. A piece Skweir

has been working on sat atop a drum mounted with part of a car

tire to prevent slippage. "After

you pound it down into a bowl, you mark the areas for each note,

and with a punch you make a groove around each note. The groove

forms an edge so you know where to hit when you play, and it

allows you to see on the inside of the drum so you know where

you're working from the inside."

"After

you pound it down into a bowl, you mark the areas for each note,

and with a punch you make a groove around each note. The groove

forms an edge so you know where to hit when you play, and it

allows you to see on the inside of the drum so you know where

you're working from the inside." The

next step was an evolution of the metal rhythm section with the

tins supplemented by clanging on pots, pans, auto parts and whatever

steel and iron was portable.

The

next step was an evolution of the metal rhythm section with the

tins supplemented by clanging on pots, pans, auto parts and whatever

steel and iron was portable.