|

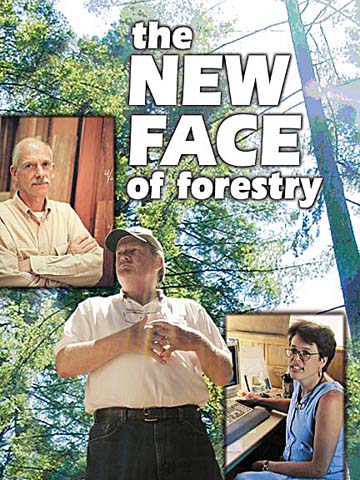

by ARNO HOLSCHUH JIM ABLE (middle in above photo) WAS WORKING AS A FORESTER FOR LOUISIANA PACIFIC Corp. in the early '70s he was given two plots of land to manage under two different systems. "I clearcut 40 acres and I thinned 40 acres, and the money I saved clearcutting wasn't enough to spit on." That got him thinking. When he left the company later that decade and went into business for himself, he started managing a 75-acre plot of timberland near Blue Lake using an unusual thinning process: Instead of taking out the larger trees and leaving the smaller ones to grow, they harvested only the least valuable trees. The best placed, most genetically fit trees were allowed to grow to their full potential. It paid off. "By thinning, the landowner made $1,000,000 (cutting timber) from 1982 to 1995, and the land itself is now worth about $1,000,000," Able said. By comparison, Able estimates that if the landowner had clearcut and sold all his timber, and subdivided the land in 1982 he would have made about $200,000. Able's kind of forestry is catching on. More and more players in the timber industry -- landowners, foresters, mills owners and retail merchants -- are at least partially switching over to a more sustainable approach to growing and harvesting trees. Certification is a big part of that switch. Once landowners switch to gentler forest stewardship practices, they can sign up with certification programs that police their behavior and reward them by labeling their products as "certified sustainable." The idea is that those who do good should be rewarded by being able to charge a higher price for the products, in much the same way as organic produce fetches a premium price. The Institute for Sustainable Forestry in Redway operates one such certification program. The institute is an affiliate of the SmartWood Program, an international certification program that inspects and tests the land management of foresters and plots of land, ensuring that certain forestry practices are adhered to. Once the wood leaves the forest, SmartWood inspects mills, manufacturers, distributors and retailers to see if the wood is being kept separate from non-certified wood. A chain of custody is established between the stump and the shelf, where conscious consumers can choose to pay a bit more for "greener" wood. "Certification is a way to give the landowners who do participate a reward," said Jude Wait, community economic development director for the institute (right in photo at top) -- and to give the forest a helping hand at the same time. THE FOREST On a recent tour of the plot near Blue Lake, dappled sunlight filters through the canopy onto ground carpeted in dark green ferns. Trees of all ages and sizes are mixed together along with the flora and fauna of the forest. And towering above are the giant timbers Able has been managing for 20 years, stately redwoods and firs that seem to preside over the rest of the forest vegetation and activity. There are stumps, of course, fresh ones, some quite large. This is timberland, after all. But that's exactly why about two dozen people are touring the land with Able that day. They are participants in a SmartWood seminar and they want to learn more about the program from Able, a SmartWood certified resource manager. The mix of woodworkers, foresters and landowners was clearly impressed with what they saw. They crowd around Able to hear about variable habitat, skid trails and checking for spotted owl nests. And about those stumps -- Able can tell you the story behind each one of them: why he cut it, when he cut it, what he was trying to achieve. Walking the plot with him, it becomes clear how intimately he knows this land. "Part of the problem of logging like this is you get to love the forest and don't want to cut any of the trees," he said with a smile.

There's some truth to the joke. Able is serious about protecting the health of this property and can tell you about tree fallers he had to fire for being careless or for felling trees that were not specifically marked. It's not all about love of trees. Able has found that by working with the forest, he can harvest a limited amount of wood from the plot while increasing the amount of boardfeet it contains. In short, he takes timber out and leaves even more behind. Able's management philosophy is based on the idea that "good" trees -- well-placed, straight, cylindrical ones -- will use more efficiently the extra space, sunlight and moisture left by falling a few lesser quality trees. They grow so quickly that they more than replace the amount of wood that was taken out. And because the forest is never clearcut, it continuously provides better habitat. Selective cutting has been around for a long time and is a widely used strategy. But most selective cuts aim to take out the most valuable timber, leaving the worst stock behind. That, Able said, is a long-term recipe for clearcutting, because it reduces the good stock to manage. Eventually, one is left with nothing valuable, and you have to start over. "I'm not opposed to clearcuts once in a while, if there's nothing left to manage." Selective cutting isn't the only approach to sustained-yield harvesting. In an area management program, small portions of a landowner's timberland are clearcut and allowed to regenerate for several decades. But that won't happen in this particular forest. Able looks at his prize trees on the Blue Lake plot as a long-term investment he is managing for his client -- and he doesn't want to reduce the amount of capital. "Basically, what sells our business is the business," he said. In other words, it's the money, in combinations with environmental and ethical considerations, that makes this forestry worthwhile. Unfortunately, the business end of certification hasn't caught up yet. Certified logs do not yet fetch a premium price. "We haven't seen an appreciable increase in price for the logs from green certification," he said. Still, Able says, his type of selective logging makes good business sense. Citing an average 9 percent increase per year in the price of timber over the past 20 years, Able said that when people ask him how to make money off of their timber, his standard response is, "Don't cut it." With timber prices increasing that rapidly, often it pays more to grow wood than it does to harvest.

THE MILL Tan oak is an indigenous hardwood that grows rampant on much Humboldt County timberland. It has long been treated as a nuisance, but Jude Wait, spokesperson for Wild Iris, wants to change that. She thinks that it could eventually become a key to creating a local certified forestry industry. "Having a local market for hardwoods makes it more feasible for a local landowner to get involved in certification, because they have more hardwoods and less softwoods," Wait said. The Wild Iris Mill, which is owned by the Institute for Sustainable Forestry, could be such a market.

Wild Iris is focusing on efficiently processing tan oak and other hardwoods. In the past, most people who wanted to mill their tan oaks have had to use portable sawmills, which have a limited capacity. The mill would help create an economy of scale, making tan oak management more profitable. Wait said that learning how to mill a tree that has "never been a commercial species" hasn't been simple. "You have to learn how to handle it, and we're not in the East or the Midwest, where they've had a long-running hardwood industry," she said. But the rewards are worth it. "It's wonderful wood," Wait said, and she can point to several tan oak products in her office to prove it. The wood is bright, blonde and beautiful, if prone to knots. It lends itself to hardwood flooring. Could mills like Wild Iris bring back the boom days of the timber industry by tapping a new resource? Wait said, "Those aren't the kind of good old days we need, because we didn't add value to our community. "I think the only way to do what we want to do is to start over. We want small operations, operating locally." The aim, she said, is to preserve nonindustrial forests. "There are a lot of nonindustrial forest landowners. It's very democratic," she said. In order to help small nonindustrial landowners become part of a new forestry industry, the mill needs to communicate, create a flexible manufacturing network, keep adding value to the community, keep adding jobs, and then, she said, "We can keep our independence." First they need to stay in business. "Several companies have gone bankrupt doing hardwood," she acknowledged. "We have a little more work to do to prove it's viable."

THE MARKET Theoretically, Eric Almquist should be charging more. (left in photo at top) Almquist, owner of Almquist Lumber in Blue Lake, is one of a few area lumber retailers selling SmartWood-certified forest products. So far, Almquist said, he has found that consumers are not yet willing to pay more for certified wood. "Hardly anyone has said, `I have to have certified,'" he said. And those who are asking for it tend to be looking for eastern hardwoods -- cherry, maple and oak. If the retailer can't get a higher price for the SmartWood-certified lumber, neither can others in the industry who grow, harvest and mill the product. So why does he do it? Human conscience is a factor. So is time -- as in time to educate consumers so that eventually there will be a demand for certified wood just as there is a demand for organic produce -- and at higher prices. "One part of forestry marketing has really bought into it because we believe in it," he said. And he doesn't see a reason to attempt to charge more for it because what he really wants to do is encourage the idea of certified forestry. "I want to charge less to put more in the marketplace." Other retailers seem to be thinking along the same lines. Major wood consumers and retailers Home Depot and Ikea have started marketing SmartWood products. And even though retailers like Almquist haven't yet seen a significant market develop, several major cities have adopted buying policies that encourage purchasing certified lumber for public works projects including New York, San Francisco, Seattle, Portland and Los Angeles. Arcata not only buys certified wood for its building projects, it also manages a portion of its community forest using SmartWood certifed forestry. And it looks like others will come around. In a recent poll of 700 architects and builders, 68 percent said they believed the number of "environmentally considerate" building supplies they use would increase. If and when the market does develop, the supply will be ready. In 1995 5 million acres of timberland were managed under certified programs. By 2000 that number had jumped to 50 million. But until that day comes, certification programs and the kind of forest practices they encourage are dependent on people like Able, Wait and Almquist. IN THE NEWS | IN THE GARDEN | CALENDAR Comments? E-mail the Journal: ncjour@northcoast.com © Copyright 2000, North Coast Journal, Inc. |

![[photo of group in forest]](cover0727-group.jpeg) Jim Able discusses his sustainable approach to growing and harvesting

trees.

Jim Able discusses his sustainable approach to growing and harvesting

trees.![[photo of mill]](cover0727-sawmill.jpeg) Mark Whittaker at the Wild Iris Mill.

Mark Whittaker at the Wild Iris Mill.