|

IN

THE NEWS | IN

THE GARDEN | CALENDAR

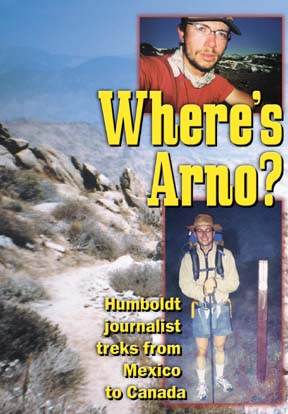

Story & photos by ARNO HOLSCHUH

IT'S SLOW GOING, WALKING ACROSS

A SNOWFIELD.

Each step forward is a process:

I put a foot down, tentatively, making sure the snow's crust

will hold my weight, then scout around for my next step, slowly

drawing the other foot up and setting it gently down. I can see

that I'll be spending a lot of time in the snow today.

Snow blankets the valley I'm

in, it sits on the peaks around me, coats the frozen lake below

me. Everywhere I look is white a blinding, cold, harsh white

that reflects up from the slushy ice. I've forgotten my sunglasses

and can barely stand the brightness of sunlight reflecting up

from the ground beneath me. My feet are soaked with melted snow,

my hands are numb from reaching down to steady myself on steep

slopes. Snow has become the most important thing in my life,

with more power over my happiness than credit card bills, the

National League pennant race or anything else I am accustomed

to caring about.

I shouldn't be surprised at

the icy conditions; it is late June, but when you're in the High

Sierra, the snow often lasts until August. And I am definitely

in the High Sierra: I'm approaching Muir Pass, a 12,300-foot-high

notch between steep granite monoliths that stretch another thousand

feet up on either side.

After hours of painstaking work,

I finally reach the pass. A new ragged set of peaks stands watch

over a new valley, and a new expanse of white awaits me. A low

stone hut built by the Sierra Club in the 1930s stands to my

left, and I watch idly as a marmot a high-altitude mammal that

looks approximately like an overgrown chipmunk comes out of it

to greet me.

I want to go inside that hut,

sit down and take a break, eat a meal, maybe sleep for a couple

days, but that's not going to happen. I can't afford to lose

any time I still have another 20 miles to hike today.

After all, Canada isn't getting

any closer with me just standing here.

A "thru-hiker" A "thru-hiker"

Canada? No, I'm not on the run

from the law or dodging the draft. I'm a "thru-hiker"

on the Pacific Crest Trail.

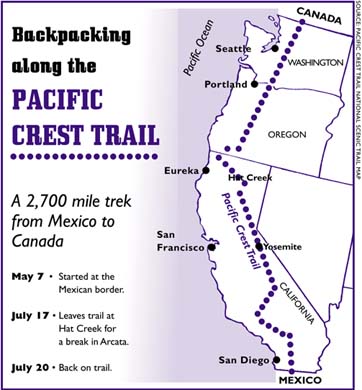

A 2,700-mile-long path that

runs from Mexico to Canada, the PCT passes through desert, swamp,

volcanic wastelands, lush green forests, three states and several

distinct mountain ranges. Each year, around 300 people attempt

to hike the entire thing. This year I'm among them, rising each

day with the sun and falling asleep just after dark some 25 or

30 miles further. Right now, I'm halfway done, having just completed

mile 1,300.

And believe me, every one of

those miles has counted. When you're driving, it's easy to let

distance just sort of slip under your wheels. You can make it

from Trinidad to Texas in a matter of days and never really notice

the land. When you're walking, though, each mile has its own

significance, its own challenge and potential for adventure.

And adventure comes in spades.

It can be cresting a desert ridge just in time to see a coyote

melt away into the cactus and scrub right in front of you. It

could be hiking at night under a canopy of the brightest stars

you've ever seen. Hearing a rattlesnake's unmistakable hiss and

clatter may not sound like fun, but it's quite a rush.

One morning in late May, I woke

up to find a thin layer of frost on my sleeping bag. Even though

it was an inauspicious beginning to my day, I had to laugh; I

was in the desert and I knew the temperature would be getting

into the triple digits by early afternoon. But just then it was

nothing but cold, and my light clothing wasn't enough to keep

the shivers off my body. I started hiking, hoping to get warm

through exertion. After about an hour, my hands still felt like

ice cubes and my mood was not improving. Then I saw the hot springs.

Tucked away into a little ravine

was a group of three hot springs, all of them channeled into

little pools for passersby to soak themselves. I scurried down

to the springs, nodded hello to the tribe of naked hippies who

seemed to pretty much live inside the water, and soaked the lingering

memory of that frost right out of my body.

Life is full of pleasant surprises

on the PCT.

Befriending

pain

It is well that it is so, for it is also full of

pain. The human body is an amazing thing and can adapt to a wide

variety of conditions. One thing it was definitely not designed

to do, however, is hike 30 miles a day. When you stress your

body, it complains, and the language of a body's complaint is

pain. You grow closely acquainted with pain; it is not a monolithic

sensation, but rather a broad spectrum or palette. There's the

incessant sharp biting pain of a blister, the slow ache of a

muscle being pushed too hard, the tender sensitivity of a sunburn. It is well that it is so, for it is also full of

pain. The human body is an amazing thing and can adapt to a wide

variety of conditions. One thing it was definitely not designed

to do, however, is hike 30 miles a day. When you stress your

body, it complains, and the language of a body's complaint is

pain. You grow closely acquainted with pain; it is not a monolithic

sensation, but rather a broad spectrum or palette. There's the

incessant sharp biting pain of a blister, the slow ache of a

muscle being pushed too hard, the tender sensitivity of a sunburn.

But it's amazing what you'll

put up with. Blisters are the most obvious example: Everyone

gets them, especially at the very beginning of the hike, when

you are walking across scalding-hot sands with fresh, soft feet.

They become part of your life. I had an angry red spot the size

of a quarter on the ball of my left foot that stubbornly refused

to heal for a month. I eventually realized that the constant

stream of expletives I was directing at the trouble spot didn't

seem to be speeding the recovery process, so I started making

friends with it instead. I named it "Alien Baby" and

would periodically check on it just to make sure it was doing

all right. The change in attitude made all the difference in

the world.

Sound crazy? One does tend to

go a little bonkers when stuck in the wild for so long. I hike

alone, and the isolation breeds eccentricity. Take my patented

hilltop ritual: When I get up over a high pass or a particularly

difficult hill, I always make it a point to do a cheesy dance

and sing a verse from a cheesy R and B song I hear constantly

on the tiny little radio I carry. ("So fresh and so clean"

by Outkast, just in case you're curious.) If that doesn't sound

like a symptom of insanity, you obviously have never seen me

dance.

And without the external stimulus

of human interaction, the brain starts to manufacture its own

conversations. I have had internal discussions about the intelligence

of cats and composed soliloquies about the importance of being

polite when struck in traffic.

Once, I spent three days in

an intense debate about whether the idea of nation-states made

any sense. All the while, the pine trees and cactus were scrolling

past me in an eternal parade. If the lizards watching me from

the sunbleached rocks along the side of the path thought it strange

when I would abruptly stop in my tracks and start thinking out

loud, they didn't mention it.

It's the kind of behavior I

would never engage in if I wasn't alone. But with the exception

of other hikers -- and they are sparsely distributed I live a

lonely life right now. That's one reason that my occasional trip

into a small town to resupply can be so much fun.

About twice a week, I'll hitchhike

or walk into some tiny little outpost of civilization and pick

up a package of food I've mailed to myself at the post office.

Usually, I then go to the nearest store, get a beer and a package

of donuts, sit down on the curb in front of the store, and revel

in the easy accessibility of delicious empty calories. It is

as close a feeling to heaven as I have ever known.

And

the human interaction is wonderful. One sees a different side

of California in towns like Tehachapi or Agua Dulce than one

does on the coast. Eastern California's people are conservative,

pleasant, generous and straightforward, closer in personality

to Midwesterners than to the Angelenos with whom they share a

state. And

the human interaction is wonderful. One sees a different side

of California in towns like Tehachapi or Agua Dulce than one

does on the coast. Eastern California's people are conservative,

pleasant, generous and straightforward, closer in personality

to Midwesterners than to the Angelenos with whom they share a

state.

This becomes most clear when

you're hitchhiking. In areas dominated by urban residents out

on vacation -- Angeles National Forest or Yosemite, for example

-- it can take hours to get a ride. Some people scowl, others

shrug, and some look like they're apologizing. A surprisingly

large number wave happily at you from the cockpit of their enormous,

empty SUVs and continue on their way. These people want to express

their desire to pick you up without actually having to do so.

Contrast that with the average

rural resident: He or she will approach in a Ford pickup that's

getting a little long in the tooth and either pick you up or

ignore you and more often than not, they pick you up. Mountain

people are like that, straightforward and honest.

Sometimes they can be a little

bit too honest. Hitching back out to the trail after spending

a couple days in the Eastern Sierra community of Bridgeport,

I was picked up by three young millworkers who were on their

way back from an exciting evening at one of Nevada's fine uh,

gentlemen's clubs. Suffice it to say that as the ride progressed,

they shared a finer-grained picture of their adventures than

I wanted to see.

Half-way

there

My own adventure is only halfway

done. Even as I write this, my backpack sits behind me on the

floor of a friend's home here in Arcata. Tomorrow or the day

after, I'll have to stuff the gear back in the bag, walk out

to the highway, and start hitching back to the bustling community

of Hat Creek, where I left the trail.

I'll admit the idea is a little

bit intimidating. It's nice to be back in a place where water

comes out of a faucet and my conversations involve two parties.

It's a cliché, but it's

true: You never know what you've got until it's gone, and Arcata

has never seemed so nice as it does today.

But I know I'll go back soon.

I see my reasons to leave everywhere I look: the telephone bills

I don't have to pay any more, the traffic I'm never stuck in,

the alarm clocks I don't ever have to set. The simplicity of

the trail lifestyle has a very seductive call, at least after

you get used to the blisters.

After all, Canada isn't getting

any closer with me just sitting here.

Arno Holschuh was a staff

writer for the North Coast Journal from

March 2000 through April 2002. After his trek he's moving to

Berlin

to study the German alternative press on a Fulbright Fellowship.

Of calories,

the Stones and bear repellent

IT

IS NATURAL TO ASSUME THAT A PERSON trying to complete a hike

from one end of the country to the other would want as wholesome

a diet as possible. Wrong. IT

IS NATURAL TO ASSUME THAT A PERSON trying to complete a hike

from one end of the country to the other would want as wholesome

a diet as possible. Wrong.

Most thru-hikers, myself included,

eat a diet that would make your doctor and dentist scream in

horror: My staples are salty crackers, ramen, peanut M and Ms,

Snickers bars and heavily sugared oatmeal. The foods may be high

in fat and empty calories, but when you're hiking 30-mile days,

calories are pretty much what you need.

The only criteria that matter

are how much a food weighs and how many calories it has, and

I've long believed nothing has more calories per ounce than pure

junk food. My belief in this dietary strategy was bolstered when

I saw my friend and fellow hiker Mr. Bill stuffing an entire

carton of Zingers into his backpack before leaving to tackle

the Sierra.

In real life, Bill works as

a nutritionist.

[At right, fellow thru-hiker

stockpiles empty calories.]

^ ^ ^

Thru-hikers are obsessed with

pack weight, plain and simple. When you're hiking all day, you

kind of have to be, because the difference in physical condition

and morale that 10 pounds can make is enormous. To that end,

I carry a lightweight mummy sleeping bag, a tarp instead of a

tent, rope and a cookstove that burns foul-smelling (but lightweight!)

white tablets instead of gasoline. That, plus clothes, a cooking

pot, food, water and some incidentals like a toothbrush, is it.

Oh, and my one true luxury:

a CD player/radio. Even though listening to those same eight

CDs I brought is getting repetitive I think I know all the words

to the Stones' "Exile on Main Street" by heart it helps

to keep the motivation level high. And the pack is still pretty

minimal: I haven't weighed it in a while, but my guess is that

it can't be more than 20 pounds.

^ ^ ^

Every backpacker in California

has to contend with the possibility of a wild bear encounter.

Black bears are smart, strong, fast, persistent and hungry, and

they have figured out that every human is a potential source

of Oreos. And they love Oreos.

Of course, so do I. And I carried

the damn things on my back every day, so you can bet I'm going

to try to defend them. I usually hang my food in a tree, although

some bears have climbed high enough on the learning curve that

this is no longer a safe way to protect food. Most thru-hikers

try a simpler, more reckless approach: They use their food as

a pillow. This has the advantage of being effective; bears do

not relish human contact and will not usually try to take food

right out of your hands. But if they ever did, the human would

likely get a bit roughed up in the process; guarding your food

is a pretty gutsy way to go.

My favorite method is the "dirty

sock" approach. Bears are reputed to hate the way humans

smell. As you can imagine, after a few hundred miles and a few

weeks, our socks start to get pretty ripe. Laundromats can be

few and far between. It is not unusual to see a thru-hiker painstakingly

arrange his dirty socks in a protective circle around his food

bag in the hope that the bear would be so nauseated by the smell

that he loses interest. After smelling some of the socks involved,

I can assure you that they were enough to make me lose my appetite.

IN

THE NEWS | IN THE GARDEN | CALENDAR

Comments? E-mail the Journal: ncjour@northcoast.com

© Copyright 2002, North Coast Journal,

Inc.

|