|

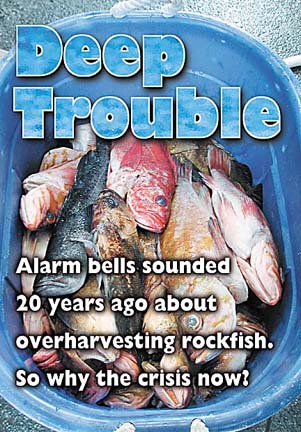

by KEITH EASTHOUSE Brightly colored, with bulging eyes, large mouths and bony spines that jut out from behind their heads, rockfish appear both comical and bizarre. Generally two to three feet long when fully grown, they are "monster predators," as one fish biologist put it, and feast on a whole array of smaller sea creatures -- crabs, shrimp, snails, other fish, even young of their own kind. They spend most of their time lurking around steep cliffs, rocky reefs, offshore pinnacles and boulder fields. Their instinct is to descend as they grow, so larger specimens are found at depth. They do not lay eggs, but instead release live young into the sea. They live for decades, in some cases even a century or longer. It's possible there are rockfish in the ocean today that were alive when Lincoln was president. Their amazing longevity comes

at a price -- they grow slowly and do not become sexually mature

until about 15 years of age; even then it takes several more

years before females hit their reproductive stride. Their low

productivity means rockfish have trouble weathering disasters

-- if their numbers drop sharply, it takes a long ti It's hard to imagine a worse disaster for rockfish than commercial trawl fishing. Huge nets drop down from above and are dragged across the ocean floor. The rocky habitat they have evolved in is smashed and scattered. The fish themselves are scooped up from the high pressure environment of the deep and brought to the surface, where the self-adjusting gas bladders that give them buoyancy at different depths swell up and explode out through their mouths. So nonspecific is trawl fishing that many rockfish that die this way are simply thrown back into the sea because they weren't what the fisherman was after. Trawlers at the Wharfinger dock. Once abundantFor a long time it seemed there were plenty of rockfish along the West Coast. A study in the early 1960s found that the average trawl cast consisted of 60 percent bocaccio, a type of rockfish found along most of the California coast. But today only a few percent of a trawler's typical catch consists of bocaccio. It is estimated that the bocaccio population has declined 95 percent since the middle of the century. No wonder. Scientists say 150,000 tons of the fish have been taken over the last 50 years -- that compares to 3,000 tons believed to be out in the ocean right now. The heaviest harvest occurred in the 1980s and 1990s, when as fate would have it ocean conditions were unfavorable (among other things, water temperatures were too warm). Bocaccio's rate of reproduction during that time period was "incredibly low," according to Alec MacCall, a bocaccio expert with the National Marine Fisheries Service who is based in Santa Cruz, Calif. "So when fishermen caught a ton of the fish the tendency was for that not to get replaced. It just stayed gone from the resource." Bocaccio is not alone among rockfish in suffering dramatic declines. A total of eight other species, including a larger category of fish called groundfish, are also in trouble: yelloweye rockfish, canary rockfish, dark-blotched rockfish, widow rockfish, cow cod, Pacific whiting, Pacific ocean perch and lingcod. The population of all these species, scientists say, has dipped below 25 percent of the number of fish there would be if large-scale commercial fishing had never happened. Under federal law, that means the species are "overfished" and must be restored to 40 percent of their "unfished" population. The problem is that it takes a very long time to bring these species back, particularly the rockfish. If all bocaccio harvests were stopped, for example, it would take 90 years for the fish to rebuild to healthy levels. If the harvest of all yelloweye was halted, it would take 158 years for the populations off Northern California to return to healthy levels and 96 years for the Oregon-Washington populations to rebuild. Leaving rockfish alone and targeting other fish is easier said than done because rockfish intermingle with a host of other commercially valuable species. Given the nonselective nature of trawl fishing, which is economically effective because it brings up fish in volume, it's often impossible to avoid rockfish; which means that relatively healthy stocks may have to go unfished so that rockfish can come back. "In order to prevent harvest of [rockfish] we have to forego harvest of other species because they occur in the same place and depth as the ones were concerned about," said Rod Moore, of the Portland, Ore.-based West Coast Seafood Processors Association. A bold -- if belated -- stepThe overfishing of rockfish

and groundfish in general is not a new problem. Allowed harvests

of certain types of rockfish have been reduced by as much as

85 percent in recent years. But with populations continuing to

decline, the Pacific Fishery Management Council, charged with

maintaining sustainable fisheries on the West Coast, took the

unprecedented step at a meeting in San Francisco last month of

announcing restrictions on commercial and recreational fishing

in the areas in which rockfish are concentrated -- approximately

10 to 15 miles out to sea, in depths from 600 to 1,500 feet deep

north of Cape Mendocino and from 300 to 900 feet deep south of

the cape. The closure south of the cape is meant to protect bocaccio,

while north of the cape the species of immediate concern is Essentially, the new restrictions are aimed at keeping sports fishermen in waters that are too shallow for rockfish and in forcing commercial trawlers into waters that are deeper than rockfish like to go. The trigger for the announcement was that the 2002 quotas for bocaccio and dark-blotched rockfish either already had been reached or were close to being reached. While the depth restrictions pertain to this year only, it is widely believed they will remain in place next year; particularly since new surveys are showing that another rockfish species, yelloweye -- found from Monterey to the Canadian border -- is in particularly bad shape. The council is also expected to impose dramatically lower annual catch limits on rockfish. In the case of bocaccio, the limit coast-wide will drop from 100 tons this year to six tons next year, according to John DeVore, groundfish management coordinator for the council. The limit for yelloweye, currently 13.5 tons, could fall as low as four tons, DeVore said, while the ceiling for yet another type of rockfish, canary, is likely to fall from 93 tons this year to 30 to 45 tons next year (canary rockfish are found up and down the West Coast of the U.S.). The restrictions have been greeted with anger by fishermen, who say that there are plenty of fish, including rockfish, in the ocean this year. "We're going back to cold water conditions, and we're seeing a lot of juvenile bocaccio out there right now," said Pete Leipzig, executive director of the Eureka-based Fishermen's Marketing Association. "It's real frustrating for fishermen." Bill Hunter, a Eureka fisherman, said, "It's a bumper crop out there right now. It's a great year. Except they won't let us fish." MacCall said ocean conditions may indeed be changing, but that that doesn't change the fact that rockfish have been severely overfished for the past 30 years and won't bounce back anytime soon. "There ought to be a lot more fish out there right now than there are," MacCall said. Leipzig questioned that, saying ocean conditions are a more powerful influence on fish stocks than fishing pressure. A huge fisheryThere are certainly more prized fish in the sea off the West Coast than rockfish -- halibut and salmon, for example. But it is the sheer number of rockfish species (55 types in all), combined with the larger groundfish grouping (83 species, including the rockfish), that gives this particular fishery its economic clout. Groundfish are popular as the fish in fish and chips, and rockfish are sold in markets and restaurants as Pacific red snapper and rock cod. Economists with the fishery council estimate that the commercial and recreational groundfish fishery generates a combined $900 million a year on the West Coast. The commercial fishery in California alone is valued at $426 million, while the sports fishery in the three states produces $246 million. Leipzig said that 85 percent

of the fish landed by the local fleet are groundfish (almost

all of which are caught by 25 trawling boats). Leipzig, whose

organization represents 500 fishermen and 130 boats from Morro

Bay, Calif., to Bellingham, Wash., said that seafood processors

are likely to be hard hit by the new restrictions. "Groundfish

is what keeps the pr Both predicted that some processors would be forced to lay off workers or perhaps go out of business altogether. They also expect that some fishermen will decide to get out. And they both predicted that the entire West Coast fishing fleet, which the industry has acknowledged is too big for the available resource, would shrink; Leipzig guessed by about 25 percent, but the fishery council is looking at the feasibility of halving the fleet. A plan to buy boats from fishermen -- boats built largely with low-interest federal loans starting in the late 1970s -- is slowly making its way through Congress. Warning signs unheededRobert Francis was perhaps the first scientist to see where things were headed. Back in the early 1980s, when he was a fisheries biologist with the National Marine Fisheries Service and a member of a panel that made recommendations to the council on groundfish issues, Francis presented a paper at a scientific conference in which he made this blunt prediction: "The U.S. West Coast domestic rockfish fisheries are, in my opinion, most likely beyond hope." Reached by telephone earlier this month, Francis -- now a professor at the University of Washington -- recalled that it was an obvious prediction to make. "It was easy for me to see it. I just looked at the production of those species that were being harvested heavily. Their production was so low that it was obvious they would be overharvested." Francis said that some types of fish, like pollock, reproduce rapidly and are capable of adding 20 percent to their population each year. "If you harvest a fish with that kind of production, you'll be fine," Francis said. But with rockfish, Francis said, "the rate of production is about 1 percent per year, which is nothing." He added: "It was very clear what was going to happen because at the time there were fairly large standing stocks of these populations up and down the West Coast." Francis likened the situation to squandering a bank account. What you're supposed to do, he said, is fish the interest and leave the principal intact; that's the key to maintaining stable fish populations over time. What happened instead? The fishing pressure on rockfish was so heavy that, in effect, the interest disappeared entirely and the principal was taken down to very low levels. "That's where we're at right now," Francis said. "The management system has really failed. It has not been able to control the declines." The management system as implemented

by the fishery council in the 1980s -- and which is still in

effec At first the system seemed to work well -- at least for the fishermen -- as the quotas were set so high that they rarely interfered with anyone's ability to make money. But as time went on, it became apparent -- as Francis had predicted -- that rockfish stocks were dwindling. The crew of the Sea unloads the day's catch. Scientists with Francis' old agency, the National Marine Fisheries Service, were monitoring the decline and expressing alarm. A chronology of their written comments on the shrinking population of bocaccio -- provided to the North Coast Journal by the Ocean Conservancy, an environmental group with an office in Oakland -- is illuminating: 1988 and 1989: Scientists express concern that the quotas "may be too high" and would likely be revised once a new stock assessment was performed (such assessments, or surveys, are performed by federal scientists once every three years). 1991: With new assessment results in, scientists warn that "the spawning biomass [of bocaccio] is probably less than 25 percent of the unfished level." 1994: After another assessment, scientists show growing alarm: "Biomass has declined substantially since 1980 and is approaching 20 percent of its estimated unfished level. There is some risk in maintaining harvests at this level." 1995 and 1996: Echoing Francis, scientists warn that "weak recruitments [meaning low reproduction rates] since 1979 will cause the stock to decline." 1997: It is "unlikely that the current stock is greater than 17 to 20 percent of the 1970 level." In other words, in a mere 27 years, the population of bocaccio -- which for millennia had teemed in the ocean off the West Coast -- had declined by 80 to 83 percent. Lowering the quotasWith each new bit of bad news -- not only about bocaccio but about other rockfish species as well -- the council responded in precisely the same manner: It lowered the annual quota. According to Francis, the first few times the rockfish quotas were lowered seemed "trivial" because the original limits had been so high. But eventually that changed -- to the point where, in Francis' view at least, quotas became "so low that no one could make a living." "They ratcheted them down to the point where they became a draconian management measure," Francis said. "Low quotas are controlling the whole West Coast fishery." Making matters worse, the quota system seemed unable to check the plummeting populations of rockfish. To an extent this was simply due to the inability of rockfish to bounce back quickly from overfishing. But another factor was at play: For the most part, only fish that fishermen caught and kept were counted against the quota; fish that were caught and thrown back -- so-called "bycatch" -- went largely unrecorded. Much of the bycatch of rockfish was simply due to the fish being inadvertently caught by trawlers who were after something else. But some of it was due to oppressively low rockfish quotas, which created an incentive for fishermen to throw rockfish back so they wouldn't be counted. The increasing bycatch wouldn't have been such a big deal if the rockfish the fishermen were throwing back were alive; but the vast majority of them were dead due to the pressure change caused by being brought to the surface. The quotas never stopped the downward slide of rockfish populations -- much less allowed them to rebuild -- because they were based on underestimates of the actual amount of fish that were caught. "We got ourselves into this situation by fishing very heavily on these stocks and then paying no attention to bycatch," Francis said. There have been attempts to estimate bycatch, but the National Marine Fisheries Service has primarily relied on bycatch data from the 1980s -- a time when quotas were relatively high and bycatch rates low. In 2001, a coalition of environmental groups successfully sued the service for failing to take into account bycatch for bocaccio and lingcod. MacCall, the biologist with the fisheries service, acknowledged that bycatch is a problem but suggested that its role in the decline of bocaccio, at least, has been overblown. "Bocaccio were rarely discarded up until a few years ago," MacCall said. "It's only been in the last few years when we've been trying to cut down on the bocaccio catch that fishermen started tossing them back in." MacCall said that last year, for the first time, the service received funding to place "observers" on fishing boats to monitor bycatch. "The observer program is really going to help. We'll be able to see what's caught before it's thrown away." MacCall said that bycatch data from the program will be made public next year. Environmentalists step inEnvironmentalists are pleased that the National Marine Fisheries Service is finally paying attention to bycatch. They are also pleased that the council is no longer relying solely on lower quotas to curb overfishing of rockfish. But they note that had these steps been taken sooner, there might not have been a need to impose the drastic restrictions that fishermen are now facing. "If (the fisheries service) had acted earlier, the fixes wouldn't have had to be as severe as the ones the council is in the process of adopting now. Obvious solutions, like closing areas for part of the year, were ignored," said Drew Caputo, an attorney with the San Francisco office of the Natural Resources Defense Council.

That domination hasn't changed -- to this day, for example, there is not a single environmentalist on the 14-member council (most of the members are appointed by governors of the three West Coast states). What has changed is that federal laws have become tougher on overfishing -- and environmentalists have started winning in court. Led by the Natural Resources Defense Council, environmentalists in just the past two years have prevailed on three lawsuits aimed at stopping the overharvesting of rockfish -- in addition to bycatch, the cases have had to do with inadequate federal plans for rebuilding rockfish stocks, and a failure to adequately involve the public in decision-making regarding rockfish. A fourth lawsuit, just filed this past spring, has to do with environmentalists' contention that the council is improperly raising the catch limit on dark-blotched rockfish at a time when scientific data shows the fish is in worse shape than ever. Caputo chose not to comment when asked if he thought the success of environmentalists in court was the reason for the council's recent bold action. But he did say this: "The facts are they weren't taking adequate action to protect the resource before they filed the suits, and after we filed the suits they started changing how they managed the fishery." A dying way of lifeWhat it all adds up to, in the end, is an industry in decline, and a way of life that appears to be dying. Ian Roberts, a McKinleyville resident who owns a small gray-white trawling vessel with blue trim called Sea, has been a fishermen for 15 years. Speaking on the Eureka docks last week as his boat was unloading fish to the local processor, Pacific Choice Seafoods, Roberts did not appear to be angry at the situation. But this soft-spoken 35-year-old, the father of two children, did seem a bit downcast as he said that he's been "barely making it" in recent years. "Plan B is that I might have to get a different job," he said. IN THE NEWS | FROM THE PUBLISHER | CALENDAR Comments? E-mail the Journal: ncjour@northcoast.com © Copyright 2002, North Coast Journal, Inc. |

me for the population

to recover.

me for the population

to recover. dark-blotched rockfish

(the cape, about 30 miles southwest of Eureka, se

dark-blotched rockfish

(the cape, about 30 miles southwest of Eureka, se rves

as a rough biological dividing line for some rockfish species

and for other fish species as well).

rves

as a rough biological dividing line for some rockfish species

and for other fish species as well).

ocessors going,"

Leipzig said. Moore of the processors group agreed, saying that

while processors could theoretically switch to other species,

"it would be difficult because groundfish has been the economic

glue that has held the processing industry together."

ocessors going,"

Leipzig said. Moore of the processors group agreed, saying that

while processors could theoretically switch to other species,

"it would be difficult because groundfish has been the economic

glue that has held the processing industry together." t -- took

the form of limits on the amount of rockfish that could be taken

each year. Instead of imposing a single quota for the entire

12-month period, however, the council broke it down into six

two-month ceilings. The purpose of this strategy was to spread

the fishing out over the entire year -- this would guarantee

fishermen steady work and processors a steady supply of fish.

"It was really the processors who wanted a constant supply

and that's what the council responded to," Francis said.

What that meant, however, was that the fish were never given

a break.

t -- took

the form of limits on the amount of rockfish that could be taken

each year. Instead of imposing a single quota for the entire

12-month period, however, the council broke it down into six

two-month ceilings. The purpose of this strategy was to spread

the fishing out over the entire year -- this would guarantee

fishermen steady work and processors a steady supply of fish.

"It was really the processors who wanted a constant supply

and that's what the council responded to," Francis said.

What that meant, however, was that the fish were never given

a break. That

more wasn't done sooner is due, in the view of environmentalists,

to the domination of the fishing industry over the Pacific Fishery

Management Council. "The fox is literally guardin

That

more wasn't done sooner is due, in the view of environmentalists,

to the domination of the fishing industry over the Pacific Fishery

Management Council. "The fox is literally guardin g

the henhouse," said Mark Powell of the Ocean Conservancy.

g

the henhouse," said Mark Powell of the Ocean Conservancy.