June 23, 2005IN

THE NEWS | DIRT | PREVIEW

| THE HUM | CALENDAR On the cover: From the deck

of the Koos King tugboat, crew member Pat Larson story & photos by HANK SIMS

A couple of miles out, the Star Eagle freighter sat idle, waiting for the tugboat to arrive. The ship, which sails under a Norwegian flag but carries a mostly Filipino crew, was stopping by Humboldt Bay to pick up pulp bound for China. The Star Eagle was halfway through a run up the West Coast. A few days earlier it had docked at Long Beach; after loading at Humboldt, it would head up to Washington before making the trip back to Asia. As the Koos King cleared the South Jetty, the outline of the massive ship was barely visible in the distance. Tim Petrusha, a harbor pilot, was the first to point it out. He remembered steering it into the bay once before, a few years ago. LEFT: The Star Eagle, a Norwegian cargo ship, enters Humboldt Bay. With Petrusha was John Powell, the only other licensed pilot on Humboldt Bay, who decided to shadow his colleague this time in order to keep his skills up. Pilots must know the intricacies of their harbor -- its channels, docks and buoys -- well enough to draw it from memory, and neither Petrusha nor Powell had been getting a lot of practice lately. The Star Eagle would be only the fourth cargo ship to enter the bay this year, only the second since Evergreen Pulp, Inc., took over the old Louisiana Pacific mill and began to move most of its product by truck. BELOW RIGHT: Bay pilots John Powell (left) and Tim Petrusha aboard the Koos King. BELOW LEFT: Gil Groszmann, captain of the Koos King

Petrusha, Powell, the Koos

King -- they, plus fewer than 20 longshoremen and the Westfall

Stevedore Co., are just about all that remains of Humboldt County's

once mighty shipping industry. Old-timers like Groszmann and

Charles Ollivier, a retired longshoreman and current member of

the Humboldt Bay Harbor, Recreation and Conservation District,

remember the Port of Humboldt's heyday in the late '60s, when

hundreds of local longshoremen serviced nearly 300 ships a year.

According to Ollivier, in 1968 the Port of Humboldt moved 5 percent

of the total cargo shipped in and out of West Coast ports. Since then, the port has been in a long, slow decline right along with the timber industry, which has always been its main source of shippable goods. But these days, promoters of the Port of Humboldt see a chance for it to recapture some of its former glory. A little investment and a good deal of salesmanship, they believe, is all that is needed to put hundreds of people back to work on the bay, with the kind of high-wage, blue-collar jobs that are so desperately scarce right now. "We've been a well-kept secret, but we're not a secret now," Ollivier said last week. "Even though it's just in the planning stages, I feel it in my blood. It's coming."

The boom On paper, the Port of Humboldt has a lot going for it -- a deep-water channel, underused facilities, vacant industrial land, an eager labor force. What has limited port development in the last few years is a lack of goods. With the timber industry down, raw logs are no longer shipped out of Humboldt Bay to distant ports; in fact, nowadays logs are occasionally shipped in, on barges, to feed local mills. But those who are placing their bets on a port resurgence are counting a new economic trend to provide the goods -- the booming West Coast trade with Asia and China's exploding industrial sector. According to a recent report by the Public Policy Institute of California, $217 billion worth of foreign goods passed through California ports on their way to the U.S. market in 2003, up 40 percent from just five years earlier. Most of that increase was from Asian countries. And the trade is not expected to slow anytime soon; by 2020, imports are expected to double from their 2003 levels. BELOW LEFT: The tug Heidi Brusco, running alongside the Star Eagle.

In recent months, David Hull, CEO of the Humboldt Bay Harbor, Recreation and Conservation District, has spent a good deal of time in Sacramento arguing that with a modest investment, the little Port of Humboldt has a lot to offer. BELOW RIGHT: David Hull, CEO of the Humboldt Bay Harbor, Rectreation and Conservation District "It's not going to be the Port of Oakland here," Hull said last week. "There's only a limited amount of land, and there's only so much you can do with it. So it's a question of making the best choices and going with it."

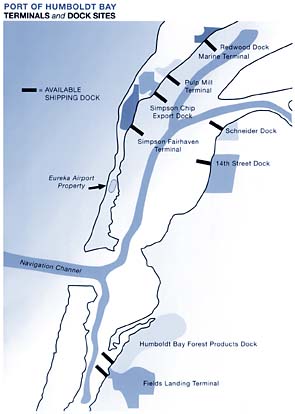

But the port could conceivably ship containerized pulp by barge, and the harbor district's immediate priority is to get that service operating. Some barges carry their own cranes with them; they can use those cranes to load the containers. Afterwards, the barge would make its way to the Port of Oakland, where that port's large cranes would move the goods onto eastbound ships. Once a regular barge service is established, the district hopes to find other producers to sign up, either to ship goods out of Humboldt with the pulp or to send goods up from the Bay Area. Finally, the district would hope to find investments to repair and modernize the local infrastructure -- including the old Simpson dock behind the Samoa Cookhouse, which it purchased last fall -- to handle container ships on its own, and to compete for some of the Asia trade.

Trade barriers As even the most ardent of believers will acknowledge, though, there are significant obstacles that the port will have to overcome if it wishes to thrust itself into international trade. For one, the shipping channel into Humboldt Bay can only accommodate ships up to 750 feet in length -- a standard length for container ships in the early '90s, when the dredging of the channel was first planned, but now woefully out of date. These days, container ships commonly range up to 1,000 feet long, or longer. Then there is Humboldt County's perennial problem, at least where industrial development is concerned. The area is just too far away from the nation's main transportation routes. Plans to fix Highway 299 at the Buckhorn Summit are just starting to get underway, but work won't be completed for many years. Until then, Humboldt County has to make do with smaller trucks than those used in the rest of the country -- hardly an attractive prospect for a company wishing to get its goods to market. Worse, the Northwestern Pacific Railroad -- key to any plan to seriously develop the local shipping industry -- is as defunct as it ever has been in these last eight years, with no serious prospects to restore service from Humboldt Bay to the Bay Area (and on to the national railroad network) in sight. (For more on the railroad's problems, see "Going Nowhere," May 29, 2003.) Even the "first phase" in the harbor district's plan -- the barge service to move pulp -- is proving difficult to realize. Andy Westfall, owner of the Westfall Stevedore Co., said last week that he has had little problem lining up barge operators who are willing to take the trade, but there are hitches. First, Westfall said, with business at the Port of Oakland being what it is, it has proved impossible, so far, to find a dock operator willing to take the barges. It's easier for such companies to handle standard truck- or rail-to-ship transfers, and there's no shortage of that kind of work. Second, it turns out that even with the price of diesel fuel through the roof, trucking the pulp down to the Bay Area one container at a time is actually cheaper than hauling multiple containers by barge. BELOW LEFT: Humboldt Bay pilot John Powell clambers up the side of the Star Eagle.

Wilson Lacy, the Port of Oakland's director of maritime operations, said Monday that he plans to speak with a consultant about how to get the service up and running, but that right now it's about "10th on my list" of things to do. He said that the major obstacle to overcome was the fact that shipping the pulp by barge appears to cost about twice as much as it does by truck. Lacy said that Oakland promotes California ports, including the Port of Humboldt, when it can, in meetings with officials in Sacramento and Washington. Jerry Bridges, the Port of Oakland's executive director, is scheduled to travel with Gov. Arnold Schwarzenegger on a trip to China later this year; he is supposed to be taking along pamphlets promoting Humboldt Bay as a shipping alternative, according to Hull. But in an off-hand comment, Lacy noted that the globalization of the economy is as likely as not to cut against the Port of Humboldt. The Mexican government is currently investing heavily to revamp the port of Ensenada, he noted, motivated by the very same economic trends that give local port boosters reason to hope. "Your competition, I would say, is Mexico," Lacy said. BELOW RIGHT: Captain Groszmann oversees the Star Eagle's docking maneuvers from the Koos King's flying bridge. Men at work In recent weeks, Charles Ollivier has given presentations at a number of local forums, touting the big-picture plan. At a recent meeting of the Citizens for Port Development, he described the tentative plans being developed by the harbor district and its consultant, Ken Davlin.

It would create about 3,000 jobs, all told, Ollivier said -- many of them with excellent, union salaries. It would cost somewhere around $200 million dollars, most of it going to railroad repair, the rest to the terminal. The money would come from public bonds, state and federal grants, private investors or some mixture of the three. Ollivier believes it can happen, given the increasing demands that will be placed on West Coast ports in the coming years. And he's working for it -- in addition to serving on the harbor district's board of directors, he is one of three Humboldt County residents serving on the board of the North Coast Railroad Authority. He thinks it's the county's last, best shot to pull itself out of the economic doldrums. BELOW LEFT: The Star Eagle at dock.

"It really makes you cry when you see the pampas grass, the abandoned buildings," he said. "All you hear are the echoes of men working." Which isn't to say that some aren't still at it, after a fashion. After dropping off the pilots on the Star Eagle Thursday afternoon, the Koos King returned and waited for the ship near the mouth of the bay. There it was joined by another local tug, the Heidi Brusco. When the ship came up into the bay, the two tugs ran alongside until they reached the Fairhaven Terminal, just down the Samoa Peninsula from the pulp mill. There, the two boats turned head-on into the ship, pushing it around 180 degrees in the middle of the channel, before pressing it up against the dock.

RIGHT: John Hokman,

Pat Larson and Tim Wing operate the Koos King's capstan. Petrusha and Powell rejoined the Koos King to catch a ride across the bay to their cars. They had put in just three hours work -- apart from a few gasoline and log barges, it was the first piloting work that any of them had had since May. Tim Wing, the joker of the group, relaxed into one of the tug's cabin chairs with a sigh. "Well, that was fun," he said. "Wouldn't it be great if we could do this for a living?" Everyone on board had a good laugh at that one.

IN THE NEWS | DIRT | PREVIEW | THE HUM | CALENDAR

Comments? Write a letter! © Copyright 2005, North Coast Journal, Inc. |

![Shipping on Humboldt Bay -- can we build it, will they come? Port of Call [photo of captain on ship]](cover0623-photohed.jpg)

![[ship in bay, buoy in front]](cover0623-bouy.jpg) THE WEATHER WAS DANK AND DRIZZLY AS THE Koos

King tugboat crossed out of Humboldt Bay into the Pacific

Ocean at around noon last Thursday, but the seas were fairly

calm. Long, rolling waves from the south lifted the boat a few

feet into the air periodically, but the powerful tug barely took

notice, motoring right through the crests.

THE WEATHER WAS DANK AND DRIZZLY AS THE Koos

King tugboat crossed out of Humboldt Bay into the Pacific

Ocean at around noon last Thursday, but the seas were fairly

calm. Long, rolling waves from the south lifted the boat a few

feet into the air periodically, but the powerful tug barely took

notice, motoring right through the crests.![[two men inside boat]](cover0623-pilots.jpg) Fifteen minutes later, the Koos King stood

along the port side of the Star Eagle's 590-foot-long

hull -- from this angle, a wall of steel rising out of the sea

as high as a three-story building. Gil Groszmann, the tug's captain,

aimed for the dangling rope ladder hanging near the ship's bow.

Powell and Petrusha moved into position. While the waves continued

to lift the boat and drop it back down, the Koos King's

crew snatched for the ladder. Then, one after the other, miles

out to sea, with the ladder swinging back and forth against the

hull, Petrusha and Powell scrambled up the side of the Star

Eagle to its deck, there to guide the ship safely to dock.

Fifteen minutes later, the Koos King stood

along the port side of the Star Eagle's 590-foot-long

hull -- from this angle, a wall of steel rising out of the sea

as high as a three-story building. Gil Groszmann, the tug's captain,

aimed for the dangling rope ladder hanging near the ship's bow.

Powell and Petrusha moved into position. While the waves continued

to lift the boat and drop it back down, the Koos King's

crew snatched for the ladder. Then, one after the other, miles

out to sea, with the ladder swinging back and forth against the

hull, Petrusha and Powell scrambled up the side of the Star

Eagle to its deck, there to guide the ship safely to dock.![[captain speaking into microphone]](cover0623-Captain.jpg)

![[man sitting on deck of his home]](cover0623-CharlesOlivier.jpg) RIGHT: Charles Ollivier, retired longshoreman and

current member of the Humboldt Bay Harbor, Recreation and Conservation

District

RIGHT: Charles Ollivier, retired longshoreman and

current member of the Humboldt Bay Harbor, Recreation and Conservation

District![[tug boat alongside ship]](cover0623-tug.jpg) This booming trade has led to

off-and-on congestion in California's major ports -- Los Angeles,

Long Beach and Oakland. All three ports are expanding their facilities

and workforces, but there are limits to how fast and how much

each of them can grow. In response to the coming crunch, Gov.

Schwarzenegger formed a cabinet-level commission to devise a

statewide strategy for expanding port facilities and transportation

networks earlier this year.

This booming trade has led to

off-and-on congestion in California's major ports -- Los Angeles,

Long Beach and Oakland. All three ports are expanding their facilities

and workforces, but there are limits to how fast and how much

each of them can grow. In response to the coming crunch, Gov.

Schwarzenegger formed a cabinet-level commission to devise a

statewide strategy for expanding port facilities and transportation

networks earlier this year.![[man standing near Port Authority boat]](cover0623-DavidHull.jpg) For now, Hull said,

there's a three-stage plan to develop the industry. First, recapture

the pulp traffic that is now mostly moving south on trucks. Evergreen

switched to trucks when it took over the mill earlier this year

because its customers are mostly geared to handle "containerized"

product -- goods that have been stuffed into industry-standard,

truck-length metal boxes that can be shifted from ship to rail

to truck with a minimum of effort. The Port of Humboldt has no

cranes, and therefore no way to load container ships.

For now, Hull said,

there's a three-stage plan to develop the industry. First, recapture

the pulp traffic that is now mostly moving south on trucks. Evergreen

switched to trucks when it took over the mill earlier this year

because its customers are mostly geared to handle "containerized"

product -- goods that have been stuffed into industry-standard,

truck-length metal boxes that can be shifted from ship to rail

to truck with a minimum of effort. The Port of Humboldt has no

cranes, and therefore no way to load container ships.![[workers in tug, below ship]](cover0623-cables.jpg) LEFT:

Koos King crew members John Hokman and Tim Wing

hook a line sent down from the Star Eagle.

LEFT:

Koos King crew members John Hokman and Tim Wing

hook a line sent down from the Star Eagle.![[pilot climbing ladders on side of ship]](cover0623-ladders.jpg) "One of the

advantages of the barging, at least in the case of the pulp mill,

is that they can load the containers heavier," Westfall

said. "But even with that, it's a struggle to beat the trucking."

"One of the

advantages of the barging, at least in the case of the pulp mill,

is that they can load the containers heavier," Westfall

said. "But even with that, it's a struggle to beat the trucking."![[Captain piloting boat]](cover0623-Grozmann.jpg) The district's new Redwood Dock

and terminal will be revitalized, he said -- the rotting dock

rebuilt and the warehouses refurbished, with hundreds of workers

inside loading and unloading containers. Perhaps, down the street,

Target or Costco will have a new regional distribution center,

with goods coming off of ship or barge sorted and trucked out

to superstores around California, Oregon and Nevada. And running

through the yard, the old Northwestern Pacific Railroad, hauling

goods back and forth between the sea terminal and the national

rail system.

The district's new Redwood Dock

and terminal will be revitalized, he said -- the rotting dock

rebuilt and the warehouses refurbished, with hundreds of workers

inside loading and unloading containers. Perhaps, down the street,

Target or Costco will have a new regional distribution center,

with goods coming off of ship or barge sorted and trucked out

to superstores around California, Oregon and Nevada. And running

through the yard, the old Northwestern Pacific Railroad, hauling

goods back and forth between the sea terminal and the national

rail system.![[ship at dock]](cover0623-stareagle.jpg) But there's some sentimentality to his thinking,

as well. His 30-odd years of longshoreman work means more to

him than the excellent salary he earned. For nearly that entire

time, he was also the union representative for the local chapter

of the International Longshore and Warehouse Union -- he knew

the union's legendary founder, Harry Bridges -- and it tears

at his heart to see the old facilities he worked at for so many

years go to seed.

But there's some sentimentality to his thinking,

as well. His 30-odd years of longshoreman work means more to

him than the excellent salary he earned. For nearly that entire

time, he was also the union representative for the local chapter

of the International Longshore and Warehouse Union -- he knew

the union's legendary founder, Harry Bridges -- and it tears

at his heart to see the old facilities he worked at for so many

years go to seed.![[workers operating winch]](cover0623-workers.jpg) Once there, the Koos King's

crew Tim Wing, Pat Larson and John Hokman -- manned the capstan

while Groszmann, steering from the flying bridge, nudged the

tug around the front of the ship. The Star Eagle sent

down a rope, which the Koos King made fast to the dock's

front dolphin. The ship was now moored, and over the next two

nights local longshoremen and casual laborers would fill its

hold with the pallets of raw pulp stored in the nearby warehouses.

The ship was set to sail for the Columbia River port of Longview,

Wash., early Saturday.

Once there, the Koos King's

crew Tim Wing, Pat Larson and John Hokman -- manned the capstan

while Groszmann, steering from the flying bridge, nudged the

tug around the front of the ship. The Star Eagle sent

down a rope, which the Koos King made fast to the dock's

front dolphin. The ship was now moored, and over the next two

nights local longshoremen and casual laborers would fill its

hold with the pallets of raw pulp stored in the nearby warehouses.

The ship was set to sail for the Columbia River port of Longview,

Wash., early Saturday.