|

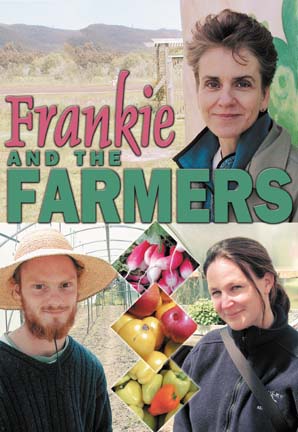

story & photos by BOB DORAN THIRTY YEARS HAVE PASSED SINCE Frances Moor Lappé wrote Diet for a Small Planet, a landmark book that helped transform the way some Americans eat. At a time when people were concerned that there wouldn't be enough food to feed the Earth's burgeoning population, Lappé came to a radical conclusion -- there was plenty of food; the problem was the pervasiveness of a meat-centered diet, one that requires feeding cattle grain that could otherwise be used to feed people. Her message may not have caught on with the masses -- obesity in the developed countries and starvation in the Third World remain major problems -- but the book sold over 3 million copies and people will tell you it changed their lives. While some merely altered their diet, cutting back on meat or becoming vegetarians, for others Lappé's work was a clarion call, one that changed their plans for the future. A few years ago, at the urging of her children, Lappé began work on a follow-up. With her daughter Anna, she traveled to five continents to meet people working to change the way we look at food and its production. The result was Hope's Edge: the Next Diet for a Small Planet, a 30th anniversary sequel that came out in February. Anna and Frances (Frankie to her friends) traveled to five continents meeting people working to change the way we look at food and its production. Lappé was in Humboldt County earlier this month to promote her new book and to deliver the keynote address at the national convention of the Consumer Cooperative Management Association. Speaking at the Masonic Hall in Eureka, she emphasized the importance of individual effort. "One of our messages has been a challenge to the view that we're all just a drop in the bucket and therefore insignificant," said Lappé. "We have to say, `Wait a minute, you know if you put a bucket out in the rain overnight, it fills up.' So being a drop in the bucket isn't our problem, the problem is we can't see the bucket, we can't see how our individual choices are adding up, that our little drops are changing the world." In Hope's Edge Lappé talks about innovations in food production that parallel efforts going on here in Humboldt County. With that in mind, the Journal asked her if she might like to take a look around and meet some organic farmers while she was in town.

We began our tour at the organic food epicenter, the Saturday morning Farmers' Market on the Arcata Plaza, the largest of four markets run by the North Coast Growers Association. We found the organization's marketing director, T Griffin, in a booth on the corner cradling her two-month old son, Levi. Griffin is among those who say their life was changed by Diet for a Small Planet. Years ago when she participated in a college study group on sustainability, the book was assigned reading. "It got me thinking about food issues and made me realize just how important farming is," Griffin told Lappé. "And look where I am today." This is Griffin's first season heading up the Farmers' Market. She's going into her fifth season running Redwood Roots Farm in Bayside, a four-acre farm that she works with a partner, Janet Czarnecki. The operation is one of several Humboldt County farms run under the Community Supported Agriculture model, a pay-in-advance system where families buy crop shares at the beginning of the year, then visit the farm each week during the growing season to select a basket full of produce. Lappé is familiar with the concept; she devotes part of a chapter in Hope's Edge to it. She wants to know what percentage of Griffin's income is derived from the farm.

Is she thinking about expanding? "We could use a few more members," said Griffin. "We figure the land can produce enough for 100 members -- we have 75 -- but we don't want to expand right now, not in acreage anyway. "We just want to do what we do better. We put in greenhouses this year; that was a way to extend our season. We can start having produce early in the spring and keep it coming longer. We want to offer the best quality to our shareholders." As we talk, we work our way down one side of the Plaza, passing flower vendors, a booth selling potted plants and vegetable starts, another offering honey and beeswax candles.

Willing Workers

Tomatoes are Pagen's specialty. He grows over 100 different varieties including a number of heirloom varieties. He sells them at all four NCGA markets, "plus I have a produce stand. And I advertise in the paper and deliver boxes of tomatoes to people. I've developed a good clientele because I give people a good price: first quality organic tomatoes for like $18.50 for 20 pounds." Lappé is ready to sign up; unfortunately her home in Massachusetts is outside the delivery area. Griffin asked about a program he uses to recruit volunteers, something called Willing Workers on Organic Farms.

Lappé wants more details. "How many hours do people have to work?" she asks. "It varies from farm to farm; I require a 40-hour week minimum. We're working more than that right now -- because we're planting, we're really busy. They'll take time off later on." "And what do they get for their work?" "They learn different farming techniques, and they get food, and they get a tent on a platform overlooking the river."

"I feel like I'm learning something important. I'd like to have my own farm someday and be able to teach other people about organic farming. It's something I would like to carry on." Her plans after this summer internship? "Actually I'm going to nursing school in the fall. It doesn't have anything to do with farming," she replies with a bright smile. You can almost see the wheels turning in Frankie's mind as she offers a suggestion. "If you know how to grow organic vegetables you could revolutionize the food services in the hospitals," she says as we depart.

Claudia's Herbs

Hers is one of 10 organic farms in Orleans. Holsinger has been there for over 20 years, and her family's farm was not the first. "It's been going on for a long time. I'd say it started 25 years ago when Norman Coates came and started farming, then Pat and Marguerite Pierce. It grew from there." Why the concentration? "It's incredibly beautiful place with clean water and clean air. It's an amazing growing zone -- it's like a banana belt out there, lots of heat. You can grow pretty much all year. We harvest from April to November." Holsinger sells a line of herbs, fresh and dried, at all four Farmers' Markets and to restaurants. She also supplies both Co-ops, Wildberries Marketplace and Eureka Natural Foods. Lappé wants to know if she's tried breaking into supermarkets that don't necessarily feature "natural" foods. "You know, years ago I went and talked to Safeway and Ray's. They were like, `You have to produce all year long for us to buy from you,' or `We have to buy from our warehouse.' We used to ship down to (a wholesale warehouse in) the Bay Area, but we're not really big enough to come to town with a load to put on the truck. It's a lot nicer to produce for this local area and sell it here where we know the market." "And how do your prices compare with a supermarket's regular chemical produce?" asks Lappé. Holsinger admits that she is unsure; she hasn't checked recently. She guesses they might be higher. Lappé says the question comes up repeatedly when she talks about organic produce. "People say, `This is all good, but only certain people can afford it.' Someone said to me once, `There's nothing more expensive than getting sick.' I think that's one of the great comebacks. "What do we pay to stay healthy in this country? We pay all sorts of money, not only for doctor's bills, but now money for gyms, vitamins and all sorts of other things. So to pay more for organic food if we have to, well, you could think of it as part of your insurance.

"Like so many other things in this society, changing people's perception is hard," adds Holsinger. "For so long food has been the bottom of the budget. You have to pay your rent, pay your utilities, put fuel in your car, then you have X amount of dollars to go shopping for food. And you try to get the cheapest food you can." She has a suggestion, one that Lappé makes in Hope's Edge -- if the government is going to subsidize agriculture, maybe it should provide some support for organic farmers to keep prices down. "A lot of the cost of organic produce is the intense amount of manual labor that goes into production versus hooking up a spray rig and spraying chemicals," said Holsinger. "Organic farming requires so much manual labor -- especially this time of year. You hand weed a bed, cultivate it with the hula hoe, then come back two days later and you go, 'What!?' And you do it again and again." How much does she work? "I can work from sun-up to sun-down and beyond -- and there are definitely days when I get tired -- but I love it. I do."

Arcata Educational Farm Our next stop is Arcata Educational Farm, a community-supported agriculture operation located off Old Arcata Road in Bayside. We are greeted by Susan Ornelas, who helped found the farm in 1993. After a tour of the garden we retreat to a greenhouse to escape the wind. Ornelas moved from Santa Barbara to Orleans 25 years ago with Norman Coates who runs a farm out there called Gem of the River. "We met in a commune," said Ornelas. "After we moved up here we invited the Pierces up, they were friends of ours. That's when the organic farms in Orleans got started. Then Norman and I broke up and I moved down to Willow Creek and started Willow Creek Farms. That was a long time ago. "We started this farm with grants, but now we're able to make it on what we grow. At first I was one of the main farmers because I had experience, now I'm paid to teach out of here through Humboldt (State). I have a class called `community agriculture' where I teach students how to farm. The students have taken over the farm. They run (it) and they earn the money."

"In terms of financing this place, it's precarious," Oliver admits. "It's up to the farmers to make their income based on the sale of vegetables, so it operates like a small business. "Last year we grossed about $23,000, which is the most the farm has ever made. There are two of us, and when you subtract the cost of doing business, I made something like $7,000 last year for working January through December. It was maybe three bucks an hour." It's not much money, but he's getting an education. What does he want to do with what he's learned? "I would like to start a farm of my own next year, although the economics of farming are pretty bleak on the small scale. I already have a second job, and I would need one if I were to start a farm. It takes a lot of capital to get to a point of efficiency where you can produce a lot of food. "You know over 90 percent of the produce grown in California is grown on a scale that is considered corporate farming. Even the organic sector is dominated by a handful of growers who grow on a huge scale. So the prices are set by large-scale growers, and no matter how good of a job you do growing, the price of lettuce or beets is going to be determined by Bay Area wholesale prices." Lappé points to the fact that Claudia's Herbs is making it, supporting a family of five farming five acres of land. "Humboldt County's situation is unique because there's a huge per capita consumption of organic produce," says Oliver in response. "There are only like 130,000 people in the county, but they support all these little farms. "When you look at places like the Bay Area, there's huge growth potential in the organic sector. There's still more growth potential here, but the competition is intense. Most of the larger growers export food out of the county. "The largest grower in Arcata, Paul Giuntoli (Warren Creek Farms), sends more than half of his food outside the county. And the Pierces out in Orleans, over half of their food goes to Sacramento and Oregon wholesalers." "Humboldt County provides less than 10 percent of its own food at this point," adds Ornelas. "The more education -- the more people become aware -- the more local production will grow."

Redwood Roots Farm Driving down Old Arcata Road on our way to Redwood Roots Farm, cattle grazing in roadside pastures remind us of the dominant paradigm -- meat is still at the center of the American diet. We come to Griffin's small farm, out Jacoby Creek Road next to the Unitarian Fellowship. The setting is idyllic, with open fields bordered by a wooded hillside; it's all part of the Jacoby Creek Land Trust, so it will never be developed. A hawk circles overhead as we arrive.

"It's by a local artist, her name is Tao," explains Griffin. "She did it in trade for vegetables. We have a lot of people who wouldn't be able to afford a share who do it through trades. Basically we'll trade for any skill we don't have, because we are produce rich -- we always have extra produce. What we don't have is cash to hire someone. And barter is one way to make this more accessible to people." It's apparent that Griffin isn't looking to get rich from farming. She goes on to explain: "We also have something we call sponsor shares. Our basic shares are on a sliding scale; members can decide where they fit on the scale. Then they can also add extra to donate for families who can't afford it at all. "We feed three or four families each season who otherwise would not be able to join. We invite them in. The idea came from an early (community-supported agriculture farm) in Ann Arbor, Mich., where my farming partner Janet (Czarnecki) worked. They're bigger; they have maybe 300 shareholders, but she said, `Let's try it here.' "We also trade for work on the farm. Janet and I do most of the work, actually I haven't done much out here since Levi was born. I'm sort of on a maternity sabbatical. Anyway, we have volunteers who come out and help us. In exchange for volunteering they get food, they also get training on how to grow food. We like to do that. Part of what we're doing here is growing new farmers. We're spreading the word in all these different ways." Before we go, I ask Griffin to pose on Redwood Roots' shiny new John Deere tractor. [photo above right] "Janet will be so jealous," she says. "It's really her baby." As T slides into the driver's seat, a proud grin breaks out on her face. I look over at Lappé and see a similar smile. I don't know what she's thinking, but it might have something to do with that bucket filling up one drop at a time.

Call the

North Coast Growers Association at (707) 441-9999

IN THE NEWS | FROM THE PUBLISHER | CALENDAR Comments? E-mail the Journal: ncjour@northcoast.com © Copyright 2002, North Coast Journal, Inc. |

The

Market

The

Market "Usually we earn anywhere from 40 to 75 percent,"

Griffin replies. "Of course we live very simply. We have

low expenses -- and we eat a lot of vegetables. It's a struggle

finding the balance between working on the farm and bringing

in the extra money you might need."

"Usually we earn anywhere from 40 to 75 percent,"

Griffin replies. "Of course we live very simply. We have

low expenses -- and we eat a lot of vegetables. It's a struggle

finding the balance between working on the farm and bringing

in the extra money you might need." Down the line we meet Dezh Pagen who runs StarBrite

Farm near Willow Creek. [in

photo at right] He shows off his

latest innovation: dried smoked peppers in varying degrees of

hotness. He has also developed a line of organic dried tomatoes.

He peels off slices for each of us to sample.

Down the line we meet Dezh Pagen who runs StarBrite

Farm near Willow Creek. [in

photo at right] He shows off his

latest innovation: dried smoked peppers in varying degrees of

hotness. He has also developed a line of organic dried tomatoes.

He peels off slices for each of us to sample. "We have four people on the farm right now

from Willing Workers," said Pagen. "It's a world-wide

organization that helps people sign up to work on farms. You

can pick a farm in California or Ohio, France, Africa or wherever.

They find us through the website." (

"We have four people on the farm right now

from Willing Workers," said Pagen. "It's a world-wide

organization that helps people sign up to work on farms. You

can pick a farm in California or Ohio, France, Africa or wherever.

They find us through the website." ( "We get a great lifestyle," says Rebecca

Pressnall, a Willing Worker from Mount Hood, Ore., [photo at right]

who jumps into the conversation after making a sale. "We

learn how to live simply and we get to learn how to organic farm,

which is the real reason we came.

"We get a great lifestyle," says Rebecca

Pressnall, a Willing Worker from Mount Hood, Ore., [photo at right]

who jumps into the conversation after making a sale. "We

learn how to live simply and we get to learn how to organic farm,

which is the real reason we came. On the corner nearest Plaza Design we meet Claudia

Holsinger. [photo at left]

She runs Claudia's Herbs with her

partner Von Tunstall on a 40-acre homestead in Orleans. "We

grow a mix of herbs, tomatoes, leeks, onions, garlic, alliums,

some fruit trees, grapes for wine production," says Holsinger,

ticking off the items off on a mental list.

On the corner nearest Plaza Design we meet Claudia

Holsinger. [photo at left]

She runs Claudia's Herbs with her

partner Von Tunstall on a 40-acre homestead in Orleans. "We

grow a mix of herbs, tomatoes, leeks, onions, garlic, alliums,

some fruit trees, grapes for wine production," says Holsinger,

ticking off the items off on a mental list. "Look at the cost of buying organic potatoes

versus nonorganic potatoes. You might think twice because they're

going to cost more. But people think nothing of going in and

buying a bag of potato chips which is equivalent to paying $8

a pound for potatoes, not to mention the health issues.

"Look at the cost of buying organic potatoes

versus nonorganic potatoes. You might think twice because they're

going to cost more. But people think nothing of going in and

buying a bag of potato chips which is equivalent to paying $8

a pound for potatoes, not to mention the health issues. She introduces student farmer Patrick Oliver and

in response to a question from Lappé he explains the farm's

complex finances. The land is part of Bayside Park and is owned

by the city of Arcata. The farm, however, is not funded by the

city, aside from the fact that there is no rent. While Ornelas

still has ties to the university, and the students get credit

for what they learn, the farm is not directly funded by the college

either.

She introduces student farmer Patrick Oliver and

in response to a question from Lappé he explains the farm's

complex finances. The land is part of Bayside Park and is owned

by the city of Arcata. The farm, however, is not funded by the

city, aside from the fact that there is no rent. While Ornelas

still has ties to the university, and the students get credit

for what they learn, the farm is not directly funded by the college

either. An Asian-style gate with flowers growing on either

side leads to a garden and a swath of lawn. There's a kitchen

shed for impromptu lunches, a vegetable washing shed built from

hay bales, two greenhouses, one for starts, another dominated

by rows of hot house tomatoes. A large painting of rainbow chard

leaves graces the outside wall of the produce distribution shed.

An Asian-style gate with flowers growing on either

side leads to a garden and a swath of lawn. There's a kitchen

shed for impromptu lunches, a vegetable washing shed built from

hay bales, two greenhouses, one for starts, another dominated

by rows of hot house tomatoes. A large painting of rainbow chard

leaves graces the outside wall of the produce distribution shed. Photo

at left: Neal latt of Avalon Farm in Orleans. "I have eight

acres of vegetables and 250 fruit trees right on the bank of

the Klamath River. last year we grew about 15 tons of produce

that we sold in Humboldt and Del Norte counties, all organic.

We sell at five Farmers' Markets a week, two in Arcata, two in

Eureka and one in Crescent City. We also supply Murphy's markets,

Ray's Food Place and about ten restaurants."

Photo

at left: Neal latt of Avalon Farm in Orleans. "I have eight

acres of vegetables and 250 fruit trees right on the bank of

the Klamath River. last year we grew about 15 tons of produce

that we sold in Humboldt and Del Norte counties, all organic.

We sell at five Farmers' Markets a week, two in Arcata, two in

Eureka and one in Crescent City. We also supply Murphy's markets,

Ray's Food Place and about ten restaurants."