|

June 16, 2005

IN

THE NEWS | PUBLISHER | ART BEAT | STAGE

DOOR

PREVIEW | THE HUM | CALENDAR

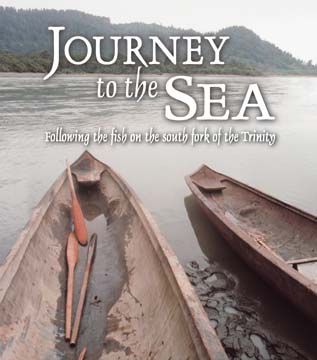

On the cover: photo caption/credit

Journey to the sea:

Following the fish on the south fork of the Trinity

story & photos by LAUREL PEÑA

DAVID SHE'OM ROSE is a man shaped

by the landscape. For 25 years he has lived on the south fork

of the Trinity River, near its remote headwaters in the Yolla

Bolly mountains, raising a dynasty of six daughters with his

wife Paula on homegrown fruit and home-baked bread. His wiry

muscles have been shaped by steep mountain trails and the hard

work of daily life. He wears buckskin clothing tanned from local

deer. His own skin is tanned by years of summer sun.

![[David Rose standing in grass in front of river]](cover0616-Rose.jpg) Rose [photo

at left] came to the South Fork

in 1980 as a self-described "young raving idealist."

He remembers the warm welcome extended by the two families already

living at the community known as Riverspirit. It was early spring

and the families had seen few visitors all winter. They boated

across the rain-swollen river to pick up the young idealist and

bring him home. Rose [photo

at left] came to the South Fork

in 1980 as a self-described "young raving idealist."

He remembers the warm welcome extended by the two families already

living at the community known as Riverspirit. It was early spring

and the families had seen few visitors all winter. They boated

across the rain-swollen river to pick up the young idealist and

bring him home.

"I grew up in Los Angeles

and always had a feeling that I was strange," he explains.

"I only really felt good when my family would go to our

cabin in the mountains around L.A., or the desert, or the ocean.

When I was 14, I realized that I was not strange. I was living

in a strange world, and I could leave."

Through the years of building

homes, taking care of livestock, home-schooling children and

other tasks, Rose maintained his ideals of living "in harmony

with my brothers and sisters and the earth." In 1997, he

founded the South Fork Trinity River Land Conservancy "to

show people the beauty of wild places and to give them the tools

to work to protect it."

But like the landscape itself,

Rose is acquainted with loss. He deeply feels the absence of

healthy salmon runs in the upper Trinity River. After years of

living on the South Fork, he says, "I realized we can't

be sustainable without the salmon. That's a crucial link."

Only native salmon return to the South Fork to spawn; the tributary

has no dams and therefore no hatcheries. Runs have been diminishing

for the past hundred years.

"I'd love to eat those

salmon! I'd love it -- that's what they come back for,"

he says. "But we just count them with Fish and Game, we

watch them, we pray for them and give thanks for them, any of

them that make it up there. We just want them to lay their eggs

and have their babies.

![[Trinity River with rafters]](cover0616-TrinityRiver.jpg) "So this year we decided

to come on down the river with those young smolts, so we could

meet some of those springers [spring Chinook salmon] that are

starting to come up now." "So this year we decided

to come on down the river with those young smolts, so we could

meet some of those springers [spring Chinook salmon] that are

starting to come up now."

Rose organized the Journey to

the Sea, a 180-mile trek from the headwaters of the South Fork

to the mouth of the massive Klamath-Trinity river system at Requa.

He brought together an alliance of local residents, river rafters,

Native fishermen, family and friends with the vision of traveling

the major tributaries of the Klamath at the time when young salmon

make their way downstream. "I always wanted to journey to

the sea," said Rose right before the journey began. "So

now I'm nearing my 50th year -- I'll be 50 years old this year,

and I'll celebrate that by sharing it with many people."

Redwoods and Rivers Rafting

offered to outfit the journey at greatly reduced cost. Separate

contingents of river lovers planned to raft the Salmon River

tributary and lower Clear Creek, both important salmon habitats.

Rose organized the logistics while effectively snowed in at Riverspirit,

miles from the nearest phone. He relied on a satellite Internet

connection as he e-mailed potential participants.

By early May the journey seemed

to be coming together. The skies were expected to be clear, for

better or worse -- better for the travelers but worse for the

salmon, facing another year of drought conditions. Then the storm

hit. It seemed as if all the rain of a northern California winter

had been held in a box that was now overturned above the Klamath-Trinity

area. Snow blanketed the headwaters. The storm went on and on,

as Rose and nine fellow travelers left the warmth of woodstoves,

said goodbye to family, and began their journey to the sea.

The mighty Klamath

The Klamath River system, of

which the Trinity is a major tributary, drains a vast area --

over 15,000 square miles of land in northern California and southern

Oregon. From the high desert around Klamath Lake in Oregon, it

flows south and west through a series of hydroelectric dams and

enters the rugged mountainous area to which it also lends its

name. Near Happy Camp, the river takes a sharp southern turn

and runs through a deep V-shaped canyon through land managed

mostly by the U.S. Forest Service. At the tiny town of Weitchpec

on the Yurok Reservation, the Klamath joins with the Trinity.

Their combined flow pushes on to the ocean, heading northwest

to reach the ocean near the town of Klamath on the Humboldt-Del

Norte county line.

In an area this large, perhaps

it is not surprising that there are many claims on the Klamath

River and much controversy. Over thousands of years river tribes

worked out an intricate policy of resource sharing that allowed

for co-existence in a potentially volatile situation: Salmon,

the basis of traditional life, had to feed one fishing nation

after another and still have enough population left to successfully

reproduce. Meanwhile the river current carried drinking water

from one village down to the next. Agreements among tribes to

maintain the health of the river were sanctified with the weight

of ceremonial practice.

Karuk fisherman and cultural

biologist Ron Reed explained this to anthropologist John F. Salter

in a 2003 interview. "The Karuk people manage their resources

by way of ceremonies and traditional rituals. There was the First

Salmon Ceremony with taboos associated. It was taboo to eat steelhead

before the Pikiawish," said Reed.

"We believed that if we

took care of our fishery we would always have food. If we didn't

manage our fishery right something bad would happen. People would

die. So we evolved with that concept. Conservation was the goal

of the ceremonies, was the goal of the way of life and it continues

that way today."

Through the disruption of European

contact, these practices were maintained among the tribes. But

they were ignored by those who planned and built dams on the

Klamath and Trinity rivers. The connections between upstream

conditions and downstream salmon runs were overlooked, as were

the rights of each tribe to the harvest. The stage was set long

ago for the tragedy of 2002.

In the fall of that year the

lower Klamath was the site of a massive fish kill that left up

to 68,000 returning Chinook salmon dead. It was a devastating

event in an area where three native tribes (the Yurok, Karuk

and Hupa) still depend on the salmon for their cultural, spiritual

and economic survival. Relative newcomers also acknowledge a

dependence on the salmon, emotionally and economically. The affected

communities blame the fish kill on upstream dams and water diversions

to farmers around Klamath Lake, a suspicion backed up by a later

California Department of Fish and Game report.

The challenge on the Klamath

seems to be this: To form new agreements between communities,

to remember the connections between upstream and downstream.

People who share a concern for the river -- from subsistence

to offshore fishermen, from environmental groups to local farmers

and businesses -- are learning how to work together for lasting

solutions.

![[Two ladies seated at table]](cover0616-ElderLadies.jpg)

![[little child looking at adult cutting salmon fillets]](cover0616-salmonprep.jpg) ![[man cooking salmon on sticks over fire]](cover0616-SalmonSticks.jpg)

Top: Yurok elders

Florina Smoker and Georgiana Trull at the Weitchpec salmon dinner.

Bottom left: Preparing the salmon. Bottom right: Yurok fisherman

Thomas Wilson oversees the cooking.

Into the wilderness

On May 14, as the journey began,

the storms had not let up. "Ten people started at the upper

part of the south fork of the Trinity River," Rose said,

"below the headwaters -- it was too snowy to get all the

way to the headwaters -- through some of the historic May storms,

the pouring rain and cold winds." Their plans to hike the

first 70 miles of the watershed were quickly scrapped. "I

went outside my house to the river and realized the water was

too high to hike it and that we were going to need to get boats."

Rafting the high flows of the

Trinity proved challenging as well. The group had to portage

around class V (expert level) rapids, hiking in soggy wetsuits.

The high water was due not only to the late spring storms, but

also to a recent change in water releases from Trinity's Lewiston

Dam. To restore spawning habitat in the main stem of the Trinity

River, a pulse of up to 7,000 cubic feet per second was released

from the dam in mid-May.

Residents of remote Trinity

River communities offered the travelers shelter and hot meals.

"The first really hard rains, we were at Riverspirit,"

said Rose. "Then we went down to Hyampom where the people

opened up their community hall to us. We had a big potluck dinner

and met with about 30 people there." Discussion focused

on the reasons for the journey -- the celebration of, and concerns

for, the river.

Along the way, some participants

took side journeys into areas included in the California Wild

Heritage bill as potential wilderness additions. "Those

areas -- there's 10 of them in the Klamath-Trinity basin -- it's

those areas that are the refugia for the native salmon."

Rose said. "That's where the native salmon come home to."

The hikers collected cedar fronds from places they visited, including

the headwaters of Red Cap Creek and Blue Creek. Both are included

in the bill. Collecting cedar echoed the old First Salmon ceremony

of the Karuk tribe, in which the aromatic leaves were brought

to the mouth of the river in order to remind the salmon of their

destinations.

The confluence of the Klamath

and Trinity rivers at Weitchpec was a major milestone in the

journey. Here, three rafters from the Salmon River tributary

of the Klamath joined the group. Others arrived by road to float

to the sea. Local residents met the travelers at a community

potluck featuring fresh-caught spring Chinook. Some expressed

concern about the size and danger of the flooded river. The attitude

of the travelers was cautious but dedicated, and very optimistic.

Rose was asked what people can hope to do when they love an endangered

place but lack political and economic power. "Enjoy it,"

he replied, with smiling eyes that suggested he was taking his

own advice.

![[group seated on river bank]](cover0616-SafetyTalk.jpg)

A boating safety lecture.

![[fishermen in boat on river]](cover0616-GillNet.jpg) ![[man fishing in waves]](cover0616-RoseatSea.jpg)

Left: Fishing. Right: David Rose

reaches the ocean.

Portents

The 2002 fish kill dramatized

the condition of the river system and helped to bring people

together at an important point in Klamath water policy. The hydroelectric

dams are currently going through a federal re-licensing process.

River activists and residents see this as an opportunity to restore

natural flows to the system by decommissioning the dams. PacifiCorp,

owner and operator of the dams, has been put on the defensive

by a flood of locally produced documentaries, rallies and other

public involvement.

In 2004, delegates from the

river tribes traveled to the Scotland headquarters of PacifiCorp's

parent company, Scottish Power. There they met with Scottish

Power CEO Ian Russell, brought the Klamath River to the attention

of stockholders and shared a salmon dinner with the public. Perhaps

their visit caused the company to think twice about their investment.

Scottish Power announced the sale of PacifiCorp to Warren Buffet's

MidAmerican Energy Holding Company last month.

Leaf Hillman, chairman of the

Karuk tribe, reacted to the news with outrage. "Mr. Russell

told us last year that we could trust him to resolve the issue

fairly. Is this his idea of fair?" Hillman asked in a press

release. "He is now attempting to evade the issue and put

it off on someone else. Mr. Russell has let us down. It's not

the first time the tribes have been treated this way."

This year looks like another

bad one. The average allowed tribal harvest, which is set every

year by tribal fisheries departments in cooperation with the

Pacific Fisheries Management Council, is between 30,000 and 50,000

fish. But state and federal agencies expect only 48,000 Chinook,

total, to return to the river this year, leaving the Yurok and

Hupa tribes with a catch limit of 8,400 fish.

"The allocation is entirely

inadequate to meet subsistence needs, let alone that there will

be no [tribal] commercial fishing this year," said David

Hillemeir of the Yurok Department of Fisheries.

![[people with giant fish ]](cover0616-IronGate.jpg) ![[people, rafts and canoes in river]](cover0616-RequaLanding.jpg)

![[canoes and rafts in river]](cover0616-SalStrioch.jpg)

TOP: Political theater at Requa.

Middle: gathering near the river's mouth.

Bottom: Salmon Stroich and Keri Norgaard paddle a canoe at Requa.

Salmon country

Participants in the Journey

to the Sea represented many different relationships with the

river system and with the salmon. In the upper tributaries of

this modern Klamath-Trinity system, salmon are often sensed as

an absence and treated with a hands-off reverence that focuses

on habitat protection and restoration. Downstream from Weitchpec

the group encountered a different relationship: The physical

interconnection of people and fish.

"That's our lifeline right

there," said Thomas Wilson looking over at the bright orange

spring Chinook salmon fillets cooking for the potluck on cedar

stakes around a fire. "If that dies, this whole region dies.

Even the coastal communities. We all depend on it." Wilson,

a Yurok fisherman, had recently pulled the salmon from the Klamath

River near his home in Weitchpec. Below the river bar where the

fire burned, the white floats of his gill net could be seen in

a calm eddy.

"Myself, I don't see why

a few special interest groups like the farmers just up the river

could take so much and not even think about the lower half. It's

a big system. It's not just one part here and one part there,

it's all together. It's one big ecosystem."

From Weitchpec to Requa the

river runs through the Yurok reservation, where traditional fishing

rights were defended by the people during the "fish wars"

of the 1970's and upheld in the Supreme Court decision Mattz

v. Arnett. Fishing is still a way of life. May is the beginning

of the spring salmon run, which traditionally was the major food

source for people along the river. The loss of spawning habitat

to dam construction is one reason given by fishermen for the

decline of the spring runs and the subsequent emphasis on fall

Chinook for subsistence fishing.

In this heavily impacted river,

all the salmon runs are declining. A 2003 survey of the Karuk

diet conducted by sociologist Dr. Kari Norgaard found that 100

years ago each tribe member was supplied with 1.2 pounds of salmon

a day, compared with less than five pounds a year now. In good

years, that is -- last fall at the Karuk traditional fishery

of Ishi Pishi only 100 fish were caught to feed a tribe of 3,000

people.

Still, people fish for subsistence

and ceremony. The rafters' routine safety lecture was enlivened

at Weitchpec with advice on how to stay out of gill nets if tossed

overboard. What was a desire, a dream and a symbol was now caught,

filleted and eaten.

This exposure to the reality

of traditional Yurok culture made a strong impression on some

participants. "When you fish the river, and you're on the

river every day -- that's the best way to learn about the river.

These people really know what they're talking about," said

Jay Silwa, a Sonoma County resident who made the journey from

beginning to end. "A lot of people go to school and take

biology and think they know a lot about the land and the river,

but these Yurok are there fishing it, watching the tides, gutting

the fish, handling them, seeing the difference between native

and hatchery fish, really getting to know this place."

Mouth of the river

On May 28, four days after leaving

Weitchpec, the small armada of six rafts and one fiberglass canoe

arrived at the mouth of the Klamath River near Requa. They were

escorted into the estuary by two traditional Yurok dugout canoes

made by Glen Moore I and paddled by the 85-year old Moore and

Walt Lara, Sr. Landing at the sand spit that encloses the estuary,

many of those who began the journey at the upper South Fork Trinity

started running towards the surf. It was the climax of a 180-mile

adventure, and, for David She'om Rose, the fulfillment of a dream.

He stood in the waves and hugged his daughter Juniper. The 13-year-old

had made the journey at his side, guiding a raft on portions

of the river trip.

![[Man and daughter drawing]](cover0616-jaysilwa.jpg) When ethnobiologist Frank Kanawha

Lake (participating in the journey as a cultural guide) was able

to bring the smiling, splashing group back together he asked

everyone to pick up a hand full of sand and look upsteam. "You're

holding the whole watershed in your hand," he said, calling

attention to the quartz, jasper, basalt, peridotite and other

stones gathered here in miniature from every headwaters of the

Klamath and its tributaries. He gave Rose a piece of kiswuf,

a root held sacred by area tribes, to throw into the waves with

the collected cedar and the prayer that there be as many salmon

as there are grains of sand -- "millions, millions." When ethnobiologist Frank Kanawha

Lake (participating in the journey as a cultural guide) was able

to bring the smiling, splashing group back together he asked

everyone to pick up a hand full of sand and look upsteam. "You're

holding the whole watershed in your hand," he said, calling

attention to the quartz, jasper, basalt, peridotite and other

stones gathered here in miniature from every headwaters of the

Klamath and its tributaries. He gave Rose a piece of kiswuf,

a root held sacred by area tribes, to throw into the waves with

the collected cedar and the prayer that there be as many salmon

as there are grains of sand -- "millions, millions."

Photo above right:

Journey to the Sea participants Jay Silwa and his daughter, Juniper

Rose

The group then listened as Lara

and Moore spoke of the historic fishery, of the days when a cannery

operated at Requa, and of the Yuroks' First Salmon Ceremony that

by Moore's estimate was last held in 1890.

At the base of Requa's cliffs

the Yurok tribe had prepared a welcoming rally and salmon barbeque.

Speakers from the tribe and from local environmental groups addressed

the crowd of around 100 people. David Rose spoke, full of emotion.

"I'm just a selfish guy, you know? I realized, `Well, if

the salmon can't make it up this river right here at the mouth,

they'll never make it up to the south fork of the Trinity!'

So it's my selfish desire I guess that brings me down here to

work with all of you to bring the salmon home."

The message of the speeches

was one of support for the cultural survival of the Klamath River

tribes, for the restoration of the salmon runs and for basin-wide

unity from Oregon, where the Klamath begins, across the mountains

to the south fork of the Trinity and down the river to Requa.

The speakers made their points with science, with storytelling

and with poetry. "Dead fish floating/through our minds,"

read Yurok poet Annalia Norris.

"Death still haunts our

waters/It is time for spirits to rise."

TOP: Walt Lara, Sr.

Middle: Glen Moore I shows one of his traditional canoes to journey

participant Caleb Soltau (left) and Curtis Kane.

Bottom: Splashing in the sea at journey's end.

IN

THE NEWS | PUBLISHER | ART BEAT | STAGE

DOOR

PREVIEW | THE HUM | CALENDAR

Comments? Write a

letter!

© Copyright 2005, North Coast Journal,

Inc.

|