|

by GEORGE RINGWALD

SHE WAS A CHARTER MEMBER OF THE REDWOOD CHAPTER OF the Sierra

Club, served it as everything from secretary to chairperson,

and when one notes that she has been with it for some time, she

remarks offhandedly: "Only about 38 years."

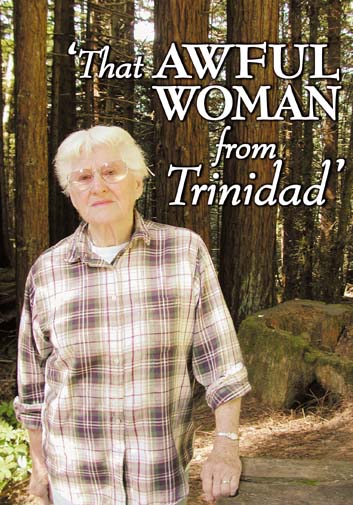

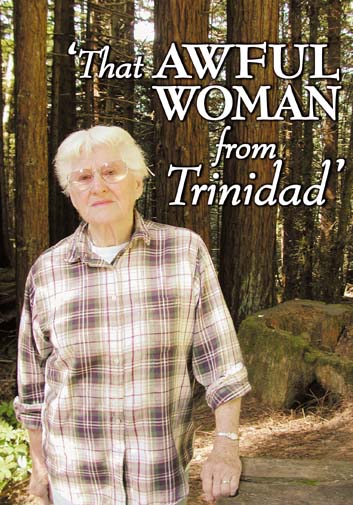

Meet Lucille Vinyard. That's

without an "e," incidentally, although she says that

"even my nieces -- and I have nine of them -- write letters

to me as `Vineyard.'"

She is a slight woman, 82 years

of age, white-haired, wears wire-rimmed eyeglasses and is dressed

in blue denim, shirt and pants, her bare feet in sandals when

she welcomes me to her frame house -- which she calls "the

oldest unfinished house in Moonstone Beach," with a positively

spectacular view of the ocean from her deck.

"Fifteen minutes before

you arrived," she tells me, "the phone rings, and it's

Ocean View Cemetery." She laughs, "And I say, `Whoa!

You don't need to go any farther. Have a nice day.' They're waiting

for me to die. I'm not ready yet."

Exactly, I agree, noting that

I'm only a few years her junior, and she scoffs: "Oh, you're

a youngster!" The woman already has me in stitches.

![[photo of Lucille]](cover0614-Lucille.jpg) Twice

widowed, she says: "I've had kind of a neat life. That first

marriage (to Leo Hull, a native Humboldter) was so great and

so much fun, and totally different than the second husband. I've

had two lives. One should be so lucky. Twice

widowed, she says: "I've had kind of a neat life. That first

marriage (to Leo Hull, a native Humboldter) was so great and

so much fun, and totally different than the second husband. I've

had two lives. One should be so lucky.

"My first husband (a widower

himself with two boys whom she helped get through high school

and college) was an outdoors man and an electrician. And through

that, he and I during World War II we end up in Alaska. I got

to see the Yukon, I got to run rivers, I got to fish, I got to

see bears, I got to play softball at midnight, I got to see the

midnight sun at Nome.

"Then I turn around, marry

Bill, three years younger than myself, never been married. Bill,

being a botanist (at Humboldt State University), he still was

the outdoor type person, and with Bill, on field trips, I learned

there's another way to look at life. So I put away my guns, put

away my fishing poles, got out my binoculars and my camera. A

whole new life for almost 40 years."

Briefly pausing, she adds musingly:

"I often thought, I wish those two men had known each other.

They would have liked each other, because of their love of the

outdoors, whether it's flowers or watching birds."

One thing she learned through

the grapevine was that Bill Vinyard (who had been instrumental

in getting Lucille into the Sierra Club) had "missed a promotion

because the president of the college at that time -- it wasn't

a big university yet -- didn't like Bill's outward stand in support

of the Redwood National park. So he stayed an associate professor

for ages and ages and ages. Now that's a closed community, I

would say." (Lucille was widowed for the second time two

years ago.)

Now the president who held back

Bill's promotion, Lucille believes, was Dr. Cornelius Siemens

-- of Siemens Hall note on the HSU campus.

"Yeah," says Lucille,

so delightfully irreverent, "the man who couldn't count

his golf score right." And as I am cracking up with laughter,

she adds: "See, I was a golfer too."

A Republican one at that, if

you can fancy that of this woman who hiked her way across the

Siskiyou Mountains, who went down the Colorado River in the fight

against damming the Grand Canyon and who stood up to politicians

and loggers in the battle to open the 58,000-acre Redwood National

Park in 1968 and then again to expand it to 106,000 acres 10

years later.

"This is ancient history,"

she relates, "but going back to when Ronald Reagan was stumping

around the country for Goldwater, (1964) he made a stop in Trinidad.

And at the time I was very active with this group of Republican

women called the Sempervirens Club, and we were responsible for

arranging for people to get there and hear the man speak. And

this man walked up to a microphone at 10 o'clock in the morning

with his face so caked with makeup, you could scrape the paint

off. And I thought, `MY GOD! We've got an ACTOR here!"

(Lucille talks quite a bit in

capital letters.)

Then at the beginning of what

she calls "the Reagan quake" in 1980, she abruptly

changed her voter registration. She says, "I couldn't STAND

the thought of Ronald Reagan."

Nor is she enamored of the man

now presiding in the White House.

"I call him Shrub,"

she says. "Every time I think of that man representing us

around the world, I'm embarrassed. And I'm sure a lot of other

people are. Isn't he something? I think people are going to begin

to wake up and see that they've been really DUPED!"

Going back to that "Reagan

quake," she says: "I was disgusted then. And then I

got sick and tired of all their little cake and bake sales. I

just realized that these women were being USED to raise FUNDS

for the next congressman or the next so-and-so for senator. I

went to more functions that I was not happy with. From dancer

George Murphy -- remember him? -- at the Eureka Inn, and you

get all dolled up, I mean in those days of stockings and white

gloves. And you meet George Murphy -- so WHAT! He wasn't fit

to go to Washington either.

"And then we had Don Clausen

(as congressman) for EIGHTEEN YEARS. I wasn't happy with that

either. Don and I remained friends, but we were always on the

opposite side of everything." She recalls that she also

had trouble with him on the Redwood National Park issue, when

Clausen sought her support of a bill that he proposed. She told

him, "No, Don, I didn't travel 3,000 miles (to Washington)

to support your bill. I want a REAL park."

She adds -- as she frequently

does: "It's been fun."

![[photo of Lucille in 1966]](cover0614-MarbleCanyon.jpg) ![[photo of Bill in 1965]](cover0614-Bill.jpg)

Lucille Vinyard in 1966 camping

near Marble Canyon. At right, her second husband, Bill Vinyarrd,

on the way to Alaska in 1965.

As it obviously was also when

loggers would try to discourage their wives from pairing up with

her on the golf course. "Because they were afraid I'd contaminate

their wives, I guess, with my Redwood Park advocacy." She

recalled too that there were times when she played at Baywood

Country club, where she was a member in those days of tea cakes

and white gloves, that she would be "tailed all the way

by loggers."

She muses: "I had no problem

at all with administrators, managers or presidents of companies.

... The lumber companies would take us on tours, they built a

trail for us one time up in Del Norte County. ... It was the

loggers and the truck drivers. They could not get it through

their heads that what they were doing was wiping out their industry,

and they wouldn't have a job eventually. They just couldn't see

that far ahead.

"And so I was `that awful

woman from Trinidad.' And then I had one man who put out a little

paper in Trinidad; he had it in for me; he couldn't write things

nasty enough about me -- `The Queen Bee and those of her ilk.'

It was so crude, nobody could take offense. When that man would

see me in Trinidad, he'd just stare at me like he wanted to put

daggers in me. And I'd smile and say, `How are you?'" She

laughs at the memory.

Lucille Vinyard -- one of five

generations of Bartletts (a great grandfather came from New England)

-- was born and grew up in Santa Cruz on what was originally

a 160-acre Spanish land grant.

"Someone in the family,"

she relates, "I think it was an uncle, mismanaged the family

finances, and it ended up in an attorney's hands -- you know,

the old `mortgage the ranch' and that sort of thing, and somehow

or other only one acre was left out of 160, and it was deeded

to one of my siblings."

She has two brothers and three

sisters, all on the far side of 70, and all alive and well. Last

year, they all went to Russia -- "we had a Russian grandfather,

you know, on the other side of the family" -- and enjoyed

a river cruise on the Neva and onto the Volga. "Three wonderful

weeks in Russia," as she tells it, and they're looking to

do it again two years from now when St. Petersburg will celebrate

its 300th birthday.

![[photo of Lucille]](cover0614-golfassoc.jpg) ![[photo of Bill and Lucille]](cover0614-Montana.jpg)

Vinyard in the Bayside

Women's Golf Association and at left on sabbatical with her husband

Bill,

in Montana near Big Fork Flathead Lake

What might be regarded as the

epiphany of Lucille Vinyard as a conservationist occurred in

Sacramento in 1965 when she was asked to make a pitch for the

Redwood National Park on the North Coast.

"I had never spoken before,"

she remembers. "I'd been a cheerleader in high school in

Santa Cruz; that was probably the noisiest I ever was."

She goes on: "So when I

got down there, I remember shoving the microphone aside when

my name was called -- my first husband always said I had a good

voice in case of fire -- so I just shoved the microphone aside

because the senator from our region had said: `NOBODY on the

North Coast wants a redwood national park.'"

This state senator, she recalls,

was a man named Carl Christiansen, an attorney from Eureka.

And Vinyard wound up her 12-minute

talk by saying: "There are TWO THOUSAND NINE HUNDRED AND

SIXTY-ONE PEOPLE (every one of those numbers in capital letters)

who've signed a petition that want a redwood national park on

the North Coast of California! And with that, he just sort of

slumped over his table, and his face turned beet-red."

It is recorded in Redwood

Needles, the newsletter of the Sierra Club's Redwood Chapter,

that Lucille "was given a rare standing ovation" by

the audience of 300.

"I don't remember that

it was `standing,'" Lucille says, "but I never expected

the place to explode."

![[photo of David Brower and Lucille]](cover0614-conference.jpg)

Vinyard at the California

Wilderness Conference with the late David Brower, first executive

director of the Sierra Club, founder of Friends of the Earth

and Earth Island Institute. She explained, "A number of

conservation elders from throughout the state elders is what

they called us we were honored for our many years of work in

the conservation efforts in California."

Still, it was a rocky road to

travel before that Redwood National Park was established in 1968.

Indeed, Lucille had bodyguards of sorts when the project was

discussed at a regional Coastal Commission meeting at Redwood

Acres.

"Everybody thought I shouldn't

go alone," she remembers, and she wound up with Tim McKay

(now executive director of the Northcoast Environmental Center)

-- "being big and strong" -- as one of her escorts.

The veiled threats, however,

didn't deter Vinyard from her Sierra Club activities. "From

1973 to 1981," she recalls, "I missed only three meetings

of the regional Coastal Commission, watchdogging for the Sierra

Club."

Dave Van de Mark, a fellow Sierra

Clubber who is now co-owner of Computer Solutions in Eureka's

Old Town, has his own vivid memories of the to-do over the Redwood

National Park.

"At the beginning, the

opponents were everyone," he said in a recent interview.

"Appreciation of parks increases with the square of the

distance that you are away from them. Then, the Times-Standard's

editor, Don O'Kane, was virtually bought and paid for by the

timber industry. All of your state assemblymen, state senators,

and your congressman for this district were all in the lap of

that industry."

Van de Mark recalls too the

opposition that prevailed at a meeting in the Eureka Muni over

the proposed expansion of the Redwood National Park in 1978.

"There was a very right-wing

anti-environmental group called Straight Arrow Coalition that

was active," he says, "and a writer active in the group

made a statement at this meeting that property rights are worth

killing for. And he got a standing ovation."

"That terrible meeting"

is how Lucille Vinyard remembers it.

"The crowd was getting

near-riotous, and I was getting scared," she says. "The

women stood on their chairs in high heels, stamping their feet,

and there were people literally hanging from the chandeliers.

The place was packed, and word came back from the stage to those

of us in front (waiting to present their testimony) that we'd

better all turn in our papers and leave separately." Which

is what they did.

"I'd never been in such

a situation before," Vinyard states. "It was scary."

She adds: "During the expansion

of the park everybody had a burr under their saddle, it seemed

-- the opposition. It was tougher to get the expansion than it

was to get the original park. Meanwhile, we had seen 10,000 acres

clear-cut in those 10 years. They were just mowing it down as

fast as they could. It was disgraceful, shocking, it was heart-breaking,

it was gut-wrenching.

"But it was the working

man. He feared for his job, and so he had it in for the environmentalists.

It was tough. You had to watch what you were doing; you didn't

want to get caught trespassing."

Of course she did -- trespass,

that is, not get caught. They had to trespass, she notes, "to

get pictures of what was going on."

Lucille acknowledges that the

Sierra Club today has its own bunch of critics, but then she

says that's nothing new.

"There's always been criticism

of the Sierra Club," she says. "Some people think they're

not strong enough. That's why Earth First! got in the act. It

makes the Sierra Club look like milquetoast. They are probably

far more willing to compromise than some of the members would

like, but there's always that.

"There's been some rhetoric

flying around for years about who's doing the work -- the volunteers

or the paid staff. Well, it works both ways; we have to work

with our staff."

What it comes down to for Lucille

Vinyard, though, is simply that it is THE SIERRA CLUB. And she

would certainly say that in capital letters.

"I think I've led a charmed

life," she says, "and through the Sierra Club I have

met some of the most wonderful people. I have met travelers,

explorers, writers, photographers, journalists. ... There was

always something going on."

She savors the moment, and the

words: "The Sierra Club. It's part of you. It's in your

blood. And oh, hiking!"

Which gives her pause, if only

briefly.

"I just gave away my backpack

last year," she confides. "I still haven't got the

heart to give away my hiking shoes. I can't bend over to tie

the shoe laces anymore, but I can get somebody to do it for me."

In fact, she said that she was

getting ready to go out that weekend, "when they dedicate

the Elk Meadow Trail up in the park."

She adds, "I'm not good

at walking much anymore. I'm having too much of a problem with

arthritis. But I'm going to give it a whirl. I'll take my cane."

As she likes to say, "It's

been fun."

BACK IN THE `60S LUCILLE VINYARD WAS SPURRED

into action when she learned that Fern Canyon was flagged as

a possible freeway route. But she did not stop after the battle

to establish Redwood Park or after fighting to see the park expanded.

"There were other things to look at:

the expansion of wilderness in the Trinity Alps; seeking protection

for the Siskyou Mountains and the Marble Mountains," she

said.

Vinyard also served on the Bureau of Land Management advisory

council. She currently represents the Sierra Club on DEAL, the

District Advisory Liaison committee for Caltrans' District 1.

She was a charter member of the Redwood Natural History Association

and still serves on the organization's board of directors.

"I continue to be involved in monitoring

the Coastal Commission on all coastal permit applications,"

she said. "I am the watchdog for the Sierra Club for the

three northern counties.

"I'm interested in everything. I continue

to keep me eye on anything that comes up at the city or county's

planning commissions on the coastal zone. That still keeps me

busy. And I watch for public notices in the paper as well as

checking the agendas they mail me. It's an ongoing thing. There's

something happening almost every day."

|

IN

THE NEWS | CALENDAR

Comments? E-mail the Journal: ncjour@northcoast.com

© Copyright 2001, North Coast Journal,

Inc.

|

![[photo of Lucille]](cover0614-Lucille.jpg) Twice

widowed, she says: "I've had kind of a neat life. That first

marriage (to Leo Hull, a native Humboldter) was so great and

so much fun, and totally different than the second husband. I've

had two lives. One should be so lucky.

Twice

widowed, she says: "I've had kind of a neat life. That first

marriage (to Leo Hull, a native Humboldter) was so great and

so much fun, and totally different than the second husband. I've

had two lives. One should be so lucky.![[photo of Lucille in 1966]](cover0614-MarbleCanyon.jpg)

![[photo of Bill in 1965]](cover0614-Bill.jpg)

![[photo of Lucille]](cover0614-golfassoc.jpg)

![[photo of Bill and Lucille]](cover0614-Montana.jpg)

![[photo of David Brower and Lucille]](cover0614-conference.jpg)