|

IN

THE NEWS | PUBLISHER | CALENDAR

![A dying breed - Humboldt's small loggers are getting regulated out of business [photo of Gary Giannandrea]](cover0508-photohed.jpg)

by KEITH EASTHOUSE

by ANDREW

EDWARDS

SITTING IN HIS OFFICE, ABOVE

HIS FEED WAREHOUSE in north Arcata, Gary Giannandrea [photo above] still

dresses like the logger he once was. A sharp-eyed, ruddy-faced

man, he's wearing the baseball cap, the ragged-cuffed jeans,

the leather boots of a woodsman. But, he quips, it's only because

he hasn't had the money to buy new clothes.

"I've employed up to 26

men, plus truck drivers at [the same] time," Giannandrea

said. "I worked solely for private ranches. I have not logged

a stick in two years."

And it's not just him. Many

other small contract loggers, self-made men who saw an opportunity,

scraped enough money to buy their first piece of equipment and

worked hard getting their businesses off the ground, have been

driven to other jobs.

Giannandrea runs his feed store,

does some trucking, and picks up whatever other opportunities

he can find on the side. Duane Willfong [in photo below],

just down the road on Giuntoli Lane, started logging in the early

`70s; these days he does mechanical work. Ken Bareilles of Eureka

is now a full-time lawyer; he passed the bar in 1969, but until

last year he'd been in the woods continuously since he bought

his first "Cat" in 1975.

While

the Pacific Lumber Co. and Sierra Pacific Industries draw the

headlines and the controversy, small loggers have ended up as

collateral damage in the region's never-ending timber wars. Some

have moved into environmental restoration work, while others

have gotten out of the forestry field entirely. Many have simply

left the area. While

the Pacific Lumber Co. and Sierra Pacific Industries draw the

headlines and the controversy, small loggers have ended up as

collateral damage in the region's never-ending timber wars. Some

have moved into environmental restoration work, while others

have gotten out of the forestry field entirely. Many have simply

left the area.

The $10 to $30-per-hour jobs

that small loggers like Giannandrea used to provide to local

men, many fresh out of high school, and the young families those

men supported, are disappearing from the North Coast.

"That's [a lot of] men

who are no longer being fed by the local economy, who have moved

out of town," Giannandrea said, referring to his work force

in years past. "These are men with families, with multiple

numbers of kids."

Why can't people like Giannandrea,

Willfong and Bareilles do the work they used to do? The reasons

are complicated, but nearly everyone interviewed for this article

agreed that the ever-increasing amount of paperwork needed to

complete timber harvest plans (THPs) in the state of California

is largely responsible.

"Very little changes in

the basic methods or rules of timber harvesting, but all this

regulatory stuff has gotten to the point where it's absolutely

ridiculous," said Willfong, sitting in his powder-blue-upholstered

camper trailer office. "It's all baloney, totally baloney.

I've got other words for it, but for the sake of this interview

it's all baloney."

Are all the regulations adding

up to greater protection for the environment? Not according to

one prominent environmental activist.

"The difference is CDF

is requiring all these regs and stuff and when you look at what's

happening on the ground nothing changes," said Cynthia Elkins,

program director for the Garberville-based Environmental Protection

Information Center. "They're stacking the record to make

it hard for citizens to take legal action. They're more concerned

about that than they are about the environmental impacts on that

land."

Steve Matzka of the Humboldt

State University Forestry Department stated the obvious -- and

summed up the problem for small loggers -- when he said: "The

more limitations, the more regulations, the higher the costs."

The

age of regulation

According to Matzka, back in

the 1960s and very early `70s it was relatively simple: If a

landowner wanted to log on his property, all he had to do was

have a professional forester fill out a form, similar to the

type still used today in Oregon and Washington state. The timber

plan was then reviewed by CDF foresters. It's not like there

weren't rules, but in many ways getting a THP was a rubber-stamp

process like registering a car at the DMV: If your ducks were

all in a row, off you went.

Then came the `70s and the passage

of two laws that forever changed forestry in California: The

Z'Berg Nejedly Forest Practice Act of 1973, which imposed a series

of restrictions aimed at reducing erosion and other damage caused

by logging; and the California Environmental Quality Act (CEQA),

which set up a procedure for reviewing the environmental impacts

of logging.

A key change was that the forestry

department no longer was the only state agency involved in reviewing

private lands logging. Instead, any state agency that had an

interest in protecting the environment -- notably the regional

water boards and the Department of Fish and Game -- could now

comment and suggest changes to THPs, beginning their transition

to cumbersome legal documents. Add in the federal Endangered

Species Act, also passed in the early `70s, and suddenly cutting

down trees had become a complicated -- and expensive -- business.

In the past 10 years more and

more analysis has been required, as new endangered plants and

animals are protected. It is all adding up to new layers of paperwork.

"We do require more information,

more thorough analysis, as things change in the academic community

and elsewhere," said Dennis Hall, deputy chief at CDF resource

management. "These projects are a lot more complicated than

even 10 years ago."

Not that the restrictions are

all bad, not even close. Loggers and environmentalists alike

have an interest in a healthy, sustainable environment, "good

stewardship," as Willfong put it.

"Every one of us has an

emotional connection to the forest," said Bill Sise, a forester

and 32-year veteran of the HSU Forestry Department.

Tracy Katelman of the Willits-based

Institute for Sustainable Forestry, a group that works to promotes

good forestry practices, said, "The regulations are in place

for a reason; the problem is the paperwork."

Donald P. Gasser of the University

of California at Berkeley, an expert on the California Forest

Practices Act, said in a recent study that while the law has

"measurably improved" soil and water quality over the

past 20 years, it has also proven "a burden wherever applied,

particularly among non-industrial private forest landowners."

The problem, he said, is a lack of flexibility; the law imposes

the same strict rules statewide, despite the fact that California's

forests are extremely diverse.

"Attempts to regulate California's

huge forest lands through prescriptive rules are seen as constraining

to management and productivity as well as expensive at all levels

of implementation," Gasser wrote in his study, based on

information provided by 23 land managers, loggers and regulators

in the private sector.

Gasser said that the minimum

preparation cost for a THP is $8,000 to $12,000, with some costing

well over $20,000 -- five to 10 times what it was a decade ago.

The greater expense has sent

private forest landowners in one of two directions, according

to Gasser: Some are cutting their lands faster and more thoroughly

so as to offset the cost of regulation and to reduce the need

to harvest in future years; others aren't cutting at all and

instead are selling their lands, either to developers who build

subdivisions or to farming interests who clear the land to make

way for other crops, such as grapes in places like Mendocino

and Sonoma counties.

A

politicized process

Of course, the economics of

forestry is not the only thing that's changed. The whole process

is also more political than it used to be.

The fact that several agencies

now review THPs has created rivalries that can get in the way

of sound decisions. "Turf battles between regulators place

more emphasis on political power than on environmental quality,"

Gasser said. While it doesn't involve small loggers, such a battle

is currently going on in the Van Duzen watershed, where the North

Coast Regional Water Quality Control Board and the forestry department

are at odds over the pace of logging on Pacific Lumber lands.

Additionally, legal challenges

from environmentalists have injected politics into forestry.

The timber wars of the late `80s and early `90s in particular

led to a flurry of environmental challenges to timber sales on

the North Coast; the impacts are still being felt today, not

least in the THPs themselves, which have became more complex

in part so that they are more easily defensible in court. What

was once a simple two-page form has turned into a document sometimes

inches thick.

Take the example of Janice and

Gordon Tosten, partners in the 5,000-acre "Stewart Family

Ranch" near Alderpoint. The Tostens have been working more

than a year on getting a Nonindustrial Timber Management Plan

for their land. It has cost them over $100,000 dollars.

To get an NTMP a myriad of surveys

has to be completed by a veritable gaggle of experts: a timber

cruise to see how much is there, a geological survey, an archeological

survey, a flora and fauna survey, a survey of any creeks and

draws. The people doing these surveys are typically paid between

$50 and $100 an hour.

After the survey work is done

things get really expensive. The various agencies responsible

for signing off come out and suggest whatever mitigation they

think is necessary: culverts for streams, improved roads, more

stable log decks -- and that's all before any actual logging

plan has been developed.

Using the Tostens' ranch as

a rough example: They are allowed to harvest 800,000 board feet

of timber each year (a board foot is a 1 foot by 1 foot piece

of lumber 1 inch thick). At $500 per thousand board feet (anything

less and "you're pretty much giving it away," Janice

Tosten said), it's worth $350,000 at the mill after "dockage,"

the portion of the tree that can't be milled. The Tostens will

see about 15 percent of that. First there's the timber plan itself

and the annual upkeep it mandates: $120,000. Then there's the

logging and trucking costs: about $154,000. Add in other costs,

like $5,000 for insurance, $5,000 for taxes, and $6,000 for yearly

owl hoot and biological studies, and the Tostens are left with

a relatively modest profit of $60,000; that's not only for them

-- they work on the ranch year-round -- it's also for the two

other families who work it with them.

Such economic realities do not

encourage light-on-the-land logging.

"If you want to do good

forestry out there you're not going to make any money,"

said Katelman of the sustainable forestry group. "If you

clearcut you'll make money, and if you clearcut and subdivide,

you're hitting the jackpot. That's not what we want to see."

The bread-and-butter timberland

owners, people with 40, 80, 160 acres of land, many of whom have

been growing the trees for years as a sort of retirement fund,

have even less of a profit margin. A small plan can run anywhere

from less than $5,000 to $50,000, depending on what happens after

it goes into agency review.

All of this leaves small loggers

who used to contract out with private

landowners competing for a shrinking

pool of employers.

Bad

market

Of course, regulations aren't

the only problem.

People wouldn't be as worried

if the timber market was like it was in 2000.

"Money can conquer all

odds," as Willfong put it.

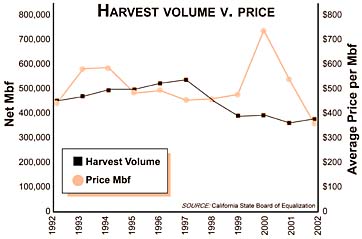

The average price for timber

coming out of Humboldt County back then was $733 per thousand

board feet. Last year that price had fallen to $349. As the season

starts this year it's hovering just below $500.

Partially that's because log

prices have been driven down by imports from less regulated areas

such as Oregon, Washington and in particular British Columbia,

which still has large swaths of old-growth. Because an economic

downturn in Asia has reduced demand, those prime logs have been

shipped down the coast to Humboldt County mills. They have a

variety of advantages.

Most importantly, they are already

processed with the useless parts of the logs (or dockage) already

removed, so the mill produces more lumber for its time.

Also, the supply is fairly steady

and can keep mills going through the winter.

"[If you use imported logs]

you don't have to be involved with the logging down here, with

all that unpredictability," said Bareilles.

There are other problems with

logging in California. The cutting season has been shortened

over the years by a month or more, in part to avoid logging during

the nesting season of imperiled birds such as the northern spotted

owl and the marbled murrelet. And workers' compensation costs

in the state have skyrocketed.

As if all that weren't bad enough,

almost no timber has been available for logging in the state

and national forests in the last year, mainly due to environmental

challenges and restrictions imposed by the Northwest Forest Plan,

which governs logging on public lands in Washington, Oregon and

northwestern California.

Possible

solutions

So what's being done? For the

past several years a group of foresters, landowners and even

some environmentalists have been working on something called

the Buckeye Forest Project. (See "The

Trail to Cooperation," Nov. 15, 2001.) They've taken

a piece of land and run it through the regulatory maze to illustrate

just how exasperating the process has become. The goal is to

highlight the system's flaws and eventually formulate some concrete

recommendations on how to improve it.

"[We're going to tell the

state] here's what's really happening," said Jim Able, the

forester who's been directing the project. "How can we give

the Legislature some specifics on how to turn this thing around

so we still get the same environmental protections, [but do it]

like other states do it? Their forests look the same as our forests

and they're not strangling their economy."

Other groups such as the Alliance

for Sustainable Jobs and the Environment, of which Katelman is

the co-chair, have been trying to bring together timber workers

and environmentalists to find common ground -- and, they hope,

figure out a way to make the system work for everyone.

"If

you're taking care of your forests you're taking care of your

workers," Katelman said.

Finally, some loggers have gone

into the environmental restoration field, where they are essentially

trying to undo the harm that results when a forest is cut.

Redwood National Park, which

contains large portions of cutover land, has long employed loggers

in such work, which typically involves shoring up or removing

logging roads, revegetating and using bulldozers to restore the

land to its original contours.

Steve Hackett got out of the

logging business in 1995 after his family was forced to sell

their 3,000-acre ranch west of Scotia. After three years of stalled

harvests because of studies mandated after the spotted owl was

listed as an endangered species, they'd been driven out of business.

"You can imagine what a

three-year delay will do for a small business with a $60,000-a-year

interest payment," Hackett said.

Now he does forestry and restoration

contract work, helping logging companies restore areas that have

been harvested. He said he misses managing his family's land.

On the other hand, he's happy to be out of the logging business.

"If you were to do a business

plan in `95 about what the prospects were, there were none,"

Hackett said. "It's even tougher now than it was then."

Tough

transitions

Meanwhile, independent loggers

are disappearing with fewer and fewer young people taking their

places.

When Willfong first went into

the logging business, he could just knock on people's doors and

ask if they wanted some logging done on their land. Regulatory

overhead was hardly a worry. Doing business that way today is

simply not possible, said Willfong, who has yet to find any logging

work this year.

Giannandrea said some small

loggers are so desperate for work that they are bidding less

for jobs than it will cost to do them.

"I don't feel that I can

be competitive because people are so hungry they're outbidding

jobs just to work," he said, adding that his primary professional

focus is his feed store.

But for those who depended on

the logging jobs that men like Giannandrea provided, there is

no fallback plan, and sometimes transitions out of the industry

can be hard.

"One of [my ex-employees]

works in the farm country now driving tractor, plowing ground,"

Giannandrea said. "And he complains to me that if it wasn't

for stealing food out of the fields he'd have a tough time making

it. You know? That's what's going on."

Sise, the long-time forestry

professor, summed it up like this: "It's kind of what happens

to these people. They just don't make transitions well. Their

fathers, their grandfathers, their brothers, their uncles have

been doing it forever. They get the dirt and the chips in their

blood. And it's hard to get out of it."

Editor Keith Easthouse contributed

to this report.

IN

THE NEWS | PUBLISHER | CALENDAR

Comments?

© Copyright 2003, North Coast Journal,

Inc.

|