|

April 7, 2005

IN

THE NEWS | PUBLISHER | PREVIEW | THE

HUM | CALENDAR

![From Grease to Gas: The biodiesel boom and the bumps in the road [man standing next to biodiesel processor]](cover0407-photohed.jpg)

On the cover: Andy Cooper

of Footprint Recycling in Arcata. Photo by Bob Doran.

From

Grease to Gas: The biodiesel boom and the bumps in the road

by HANK SIMS

AS FAR AS ANYONE CAN REMEMBER,

IAN SIGMAN was the first person in Humboldt County to make his

own automobile fuel.

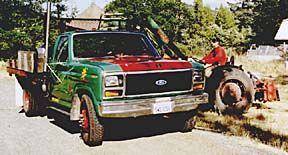

![[Ian Sigman with daughter standing in front of truck]](cover0407-IanSigman.jpg) Sigman,

who grows and markets Mama's Great-Grandma's Italian Peppers

at his Honeydew farm, first heard about biodiesel -- a version

of diesel fuel manufactured entirely out of organic material

-- sometime in the mid-'90s. There wasn't a lot of information

available, but by 1998 he had, through luck and persistence,

cobbled together enough information to try to make some of his

own. Sigman,

who grows and markets Mama's Great-Grandma's Italian Peppers

at his Honeydew farm, first heard about biodiesel -- a version

of diesel fuel manufactured entirely out of organic material

-- sometime in the mid-'90s. There wasn't a lot of information

available, but by 1998 he had, through luck and persistence,

cobbled together enough information to try to make some of his

own.

[Right: Ian Sigman

with daughter Zoe]

When his first batch was ready,

Sigman drove his truck down to the Petrolia Post office to let

everyone take a whiff of his exhaust, which smelled like fresh

donuts.

"I remember wanting to

get it out there before everyone caught on, because it was so

cool," he reminisced. "My ego really wanted to be the

first guy, but it wasn't that remarkable -- I was just following

instructions."

He was hooked. Soon, everything

down to his tractor was running on the stuff.

Sigman may have been the first,

but many have since followed. Biodiesel is getting more popular,

and it's not hard to see why. It speaks to several primal, echt-Humboldt

values. For one, it can be the product of an ingenious kind of

recycling. Take -- as Sigman did -- used deep-fryer oil, possibly

the most disgusting waste product commonly generated by human

beings. Through simple chemistry, transform it into a potent

fuel capable of powering a car, forklift, generator -- whatever.

Anything that runs on normal diesel will run on biodiesel, and

biodiesel burns much cleaner than the kind extracted from petroleum,

with fewer greenhouse gas emissions and less gunky buildup in

the engine, according the National Biodiesel Board, an industry

advocate group. All this on top of the fact that diesel engines

generally get better mileage than gasoline-powered ones.

At the same time, it holds out

the promise of energy independence. Most of the other staples

of everyday life, from food to wood to electricity, can be made

locally, but despair awaits off-the-gridders every time they

make the inevitable stop at the gas station. In the constellation

of corporate evildoers, big oil holds a special dark place in

many a heart; this may partly be due to the fact that in a rural

area, one can not simply decline to buy its products. Until recently.

Nowadays, anyone with commitment and spare time can brew his

own fuel in the garage.

Today's biodieselers may not

be the first guys on the block, but there's still a frontier

spirit to the enterprise that many find appealing. They seek

out restaurants that will agree to give them free grease, fine

tune their equipment and chat with fellow diesel-makers.

But as the scene has grown,

some of the fun may be starting to fade away. The government

has taken an interest. Also, there is now some question about

whether local restaurants can supply enough crude material to

supply the growing hunger for the product. To say nothing of

the fact that making dirty kitchen grease a part of your life

requires an unusually stout constitution.

Sigman still runs biodiesel

in his car, delivery van and farm equipment, but he stopped making

his own a few years ago. Nowadays, a Renner Petroleum truck pulls

up to his place once a year and fills a big tank on his property

with B100 -- industry terminology for pure, or "neat,"

biodiesel -- manufactured from virgin vegetable oils.

"It was a relatively simple

process, but it was not necessarily easy," he said of the

old days, when he'd schlep drums of used oil back to the farm

once a month. "Greasy, not easy. Once Renner started selling

it -- I felt that was a product I should support."

But Sigman remains proud of

the fact that the county's first biodiesel was produced just

down the road from Petrolia -- site of California's first oil

well.

Fill

'er up

![[Cassandra Culps standing behind VW van]](cover0407-CassandraCulps.jpg) Last Friday, Eureka

resident Cassandra Culps [at

right] pulled her van up to the

pump at Footprint Recycling to get a fill-up. Footprint biodiesel

goes for about $3.50 a gallon -- about a dollar more than regular

diesel -- but she didn't mind paying the surcharge in exchange

for the feeling of environmental responsibility. Last Friday, Eureka

resident Cassandra Culps [at

right] pulled her van up to the

pump at Footprint Recycling to get a fill-up. Footprint biodiesel

goes for about $3.50 a gallon -- about a dollar more than regular

diesel -- but she didn't mind paying the surcharge in exchange

for the feeling of environmental responsibility.

"You pay more, but it's

worth it," she said.

Such sentiments are music to

the ears of Andy Cooper [photo

below left] , Footprint's young,

motivated owner. From its humble beginnings as Cooper's Humboldt

State master's thesis four years ago, since opening its doors

in early 2004 Footprint has grown into a decent- sized industrial

operation, with a fleet of grease pickup vehicles and an equipment-filled

warehouse on Arcata's West End Road. The company produces about

2,500 gallons of biodiesel a month, and Cooper wants to see that

figure triple over the coming years.

In addition to showing every

sign of being a savvy businessman, Cooper is an effective evangelist

for his product and for the recycling ethos in general. On a

tour of the facilities, he pointed out how Footprint had grown

by adapting old pieces of machinery. Instead of buying an expensive

walk-in refrigerator, he purchased an old refrigerated trailer

and parked it in the yard, saving money and removing a big piece

of junk from the waste stream.

"Seventy-five percent of

the equipment that's used here at Footprint is salvaged out of

the Eureka or Arcata recycling center, or out of local farms,"

he said.

Cooper

wants to expand Footprint's biodiesel business to span the lengths

of the county. He's already got contracts with dozens of local

restaurants, charging them a nominal price for pickup of their

used oil, which would otherwise be difficult to dispose of. He's

in discussions with the North Coast Cooperative about installing

a pump at its new store in Eureka, which is scheduled to be finished

sometime next year. Cooper

wants to expand Footprint's biodiesel business to span the lengths

of the county. He's already got contracts with dozens of local

restaurants, charging them a nominal price for pickup of their

used oil, which would otherwise be difficult to dispose of. He's

in discussions with the North Coast Cooperative about installing

a pump at its new store in Eureka, which is scheduled to be finished

sometime next year.

State

wants standards

What Cooper didn't know last

week was that pure biodiesel fill-ups, like Culps had just bought

from Footprint, are now technically illegal, thanks to new regulations

from the California Department of Food and Agriculture.

David Lazier, the petroleum

products manager for the state DFA's Department of Weights and

Measures, said that his department actually enacted the ban last

fall. He said that large biodiesel manufacturers had asked the

state to impose standards on the fuel in 2003, as part of a quality-control

effort.

As no industrial standards had

been developed by national or international bodies, the department

had to put the ban into effect so that it could have more time

to research the issue, Lazier said. To help gather data, the

department built an exemption into the ban -- biodiesel manufacturers

could receive a variance, allowing them to sell the fuel to customers,

if they would agree to share data about their fuel and their

customers' experiences with the state.

"Technically, it's a misdemeanor

which could be as much as a thousand dollar fine and six months

in jail," Lazier said. "But our response would be to

talk with them and tell the procedure for applying for a variance."

Fourteen companies have already done so statewide, Lazier said,

and no one has yet been turned down.

Renner Petroleum Operations

Manager Rex Bohn said his company received a letter from the

state outlining the regulations in January. Since then, Renner

has only been able to sell B20 -- an 80 percent diesel, 20 percent

biodiesel blend -- at its cardlock stations.

Bohn said that it was a shame

that the company could no longer offer the pure product, which

he felt was a great alternative to traditional diesel or gasoline.

"It's a win-win fuel, because it helps the American farmer

and it's good for the environment," he said.

He noted that Renner customers

could still buy pure biodiesel for non-vehicular use in 5- or

55-gallon containers at the company's Eureka headquarters. It's

not clear if the ban affects home delivery of biodiesel, like

those made to Sigman's farm.

Cooper said that he was not

aware of the new regulations, but that he would be contacting

Sacramento to figure out what they were and how he would comply.

"Footprint is here to stay,

and I want people to know about it," he said. "I'm

not trying to get around anything. If we need the variance, we

will get the variance."

Home-brewed

The regulations don't apply

to the scattered few who, like Sigman in his early days, make

their own biodiesel in their garages or back yards. Lazier's

department only regulates the fuel from the standpoint of consumer

protection, not environmental protection. Except for a slightly

higher output of nitrogen oxide emissions, everyone agrees that

biodiesel is much cleaner than regular fuel, so hobbyists are

still free to put their own diesel into their own tanks.

![[Nico Kastrup standing in garage, behind barrels]](cover0407-NicoKastrup.jpg) Nico

Kastrup [photo at left]

of Fieldbrook first heard about

biodiesel when he was at mechanic's school in Southern California,

but he didn't think much about it until he moved up from Venice

three years ago. He was only 21 years old and already a trained

mechanic with a specialty in diesel engines, but he was looking

for a way to get out of the profession, as he was finding himself

more and more politically disturbed by the nation's dependence

on crude oil. Nico

Kastrup [photo at left]

of Fieldbrook first heard about

biodiesel when he was at mechanic's school in Southern California,

but he didn't think much about it until he moved up from Venice

three years ago. He was only 21 years old and already a trained

mechanic with a specialty in diesel engines, but he was looking

for a way to get out of the profession, as he was finding himself

more and more politically disturbed by the nation's dependence

on crude oil.

But Kastrup couldn't find a

job that would pay anything close to what he could earn as a

mechanic, so, recalling his teacher's cursory introduction to

the topic, he set out to learn how to make biodiesel. It didn't

take him long to plug into the county's burgeoning network of

home-brewers.

"Here, people who don't

know anything about cars, or even own a diesel, know about biodiesel,"

he said.

Kastrup runs a homemade, three-barrel

setup for manufacturing his biodiesel. He filters the oil through

a screen into the first barrel, removing burnt pieces of crud

left over from the fryer. In the second, he mixes the pure oil

with methanol and lye -- simple chemical ingredients necessary

for the biodiesel reaction. He stirs this mixture with a modified

outboard motor, letting glycerin -- a by-product -- settle to

the bottom. He then skims the pure biodiesel off the top, pumping

it into the third drum for eventual use in his Volkswagen pickup.

![[mixer and barrel]](cover0407-barrelmixer.jpg) If there's a hitch to the system, it's

that Kastrup doesn't get as much oil as he would like. He has

a steady relationship with five or six local restaurants, but

he's having a hard time signing up additional sources. Once upon

a time, there was a surfeit of used grease on the market -- with

more and more biodieselers on the scene, it is turning into a

scarce commodity. If there's a hitch to the system, it's

that Kastrup doesn't get as much oil as he would like. He has

a steady relationship with five or six local restaurants, but

he's having a hard time signing up additional sources. Once upon

a time, there was a surfeit of used grease on the market -- with

more and more biodieselers on the scene, it is turning into a

scarce commodity.

Cooper figures that only about

a third of the local kitchen oil is making its way into the biodiesel

stream; the rest is being absorbed by an out-of-county renderer

who had controlled the market for years before biodiesel came

on to the scene. He's banking the future growth of Footprint

on his ability to capture that company's business.

[Right: Nico Kastrup

uses a modified outboard motor to mix up batches in the biodiesel

manufacturing process]

No

threat to Chevron

But even that would mean little

if the goal is to wean the county off fossil fuels. A few weeks

ago, the Cascadia Scorecard Weblog, a publication of the Seattle-based

group Northwest Environment Watch, ran the numbers on Footprint's

operations and came up with a disappointing conclusion. Though

Footprint was lauded for removing fryer oil from the waste stream,

biodiesel made from the product was unlikely to solve any deep,

systemic problems with energy use.

![[Volkswagen truck with "powered by vegetable oil" painted on the side]](cover0407-vwtruck.jpg) "Humboldt

County has about 130,000 residents, and if they consume gasoline

at the state average, they use a total of roughly 4.4 million

gallons of gasoline per month," the blog's editor noted.

"That means that, even if Footprint Recycling could get

its hands on all of the used fryer grease in the county, the

company would still supply less than 0.2% of the county's transportation

fuel needs." "Humboldt

County has about 130,000 residents, and if they consume gasoline

at the state average, they use a total of roughly 4.4 million

gallons of gasoline per month," the blog's editor noted.

"That means that, even if Footprint Recycling could get

its hands on all of the used fryer grease in the county, the

company would still supply less than 0.2% of the county's transportation

fuel needs."

Some of that shortfall could

theoretically be made up with biodiesel made from fresh oil,

like the product Renner sells. For many, though, fuel made from

fresh oil doesn't have as many benefits as recycled oil. People

like Cooper and Kastrup say that part of the appeal is creating

a fantastic product virtually out of nothing -- converting fields

used for the production of food over to growing a fuel source

doesn't necessarily feel like a step forward.

But though these are all concerns,

they are not likely to deter true enthusiasts. These days, Kastrup

is taking it to the next level by converting his truck to run

on pure vegetable oil. [photo

above left] The process is a bit

more difficult, mechanically -- it requires modifications to

the vehicle -- but it has the advantage of requiring no fossil

fuel at all, as no methanol is needed to make it. Also, it's

cheaper.

"I enjoy making biodiesel,"

he said. "It's fun. But I don't want to use it as my only

source of energy. If it costs me $1 per gallon to make biodiesel

and 5 cents per gallon to filter vegetable oil, why am I doing

it?"

![[containers of biodiesel]](cover0407-testbatch.jpg) HOME-BREWING

GUIDES: HOME-BREWING

GUIDES:

From the Fryer to the Fuel Tank:

The Complete Guide to Using Vegetable Oil as an Alternative Fuel, by Joshua Tickell. Local biodieselers cite this

book as one of the most comprehensive reference volumes on biodiesel

manufacturing. Also contains information on converting cars to

run on straight vegetable oil.

"Biodiesel -- A Primer," by David Ryan. A free 14-page

pamphlet containing recipes and safety considerations. Available

for download from the National Center for Appropriate Technology

at www.attra.ncat.org.

LOCAL

RESOURCES:

Footprint Recycling: 4701 West

End Road, Arcata. 826-2606.

Renner Petroleum: 1100 W. 14th St., Eureka. 443-1645.

Nico Kastrup invites wannabe biodiesel homebrewers and restaurants

looking to get rid of grease to contact him at

834-3325 or

IN

THE NEWS | PUBLISHER | PREVIEW | THE

HUM | CALENDAR

Comments? Write a

letter!

© Copyright 2005, North Coast Journal,

Inc.

|