|

IN THE NEWS | PUBLISHER | CALENDAR

A whirlwind tour through Humboldt's

Native American lands

Story by KEITH EASTHOUSE

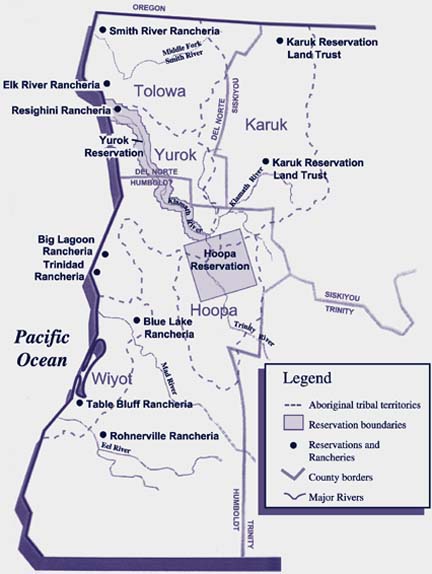

Photos by BOB DORAN MAP OF NORTHCOAST NATIVE LANDS

(at end of article)

![[photo of Klamath River]](cover0321-klamath.jpg) THE HIGH COUNTRY THAT DIVIDES THE REDWOOD CREEK AND Trinity River watersheds was mantled with snow from a storm the previous night. A few clouds still draped the highest peaks, but otherwise the sky was blue and sparkling. It was no doubt cold out there, but the chill could not be felt inside the bus that was steadily climbing a pass in an eastbound lane of Highway 299. The 20-odd passengers occupying the vehicle -- a luxury coach replete with a bathroom and kitchen -- were free to relax and enjoy the scenery. THE HIGH COUNTRY THAT DIVIDES THE REDWOOD CREEK AND Trinity River watersheds was mantled with snow from a storm the previous night. A few clouds still draped the highest peaks, but otherwise the sky was blue and sparkling. It was no doubt cold out there, but the chill could not be felt inside the bus that was steadily climbing a pass in an eastbound lane of Highway 299. The 20-odd passengers occupying the vehicle -- a luxury coach replete with a bathroom and kitchen -- were free to relax and enjoy the scenery.

Actually, not so free. Ever since the bus had left Arcata, two Native American tour guides had been taking turns talking to their captive audience through a hand-held microphone. Make that educating. As the administrative office of the Blue Lake Rancheria came into view, for example, it was explained that this small, 33-acre reservation had been "terminated" by the United States back in the 1950s -- meaning that it had lost its status as a sovereign nation that enjoyed a special relationship with the federal government and was largely exempt from state regulation. The same thing happened to the rancherias of Rohnerville and Table Bluff (both located south of Eureka), one of the guides, Merv George Jr., [photo below left] said. "From the '60s to the '80s, they did not exist as federally recognized tribes," George added. Blue Lake and Rohnerville, along with 15 other terminated tribes in California, were "unterminated" -- meaning their sovereign status was restored -- in 1983 as a result of a class-action lawsuit, explained the other tour guide, Mary Risling. [photo below right] Table Bluff regained its status through a separate legal judgment, Risling added. Today, the Blue Lake Rancheria, located within the traditional territory of the Wiyot people who lived around Humboldt Bay, runs a vegetable and flower cultivation business, Risling said, and is building a casino. ![[Merv George]](cover0321-merv.jpg) Risling then began to recite a few facts. There are more than 500 federally recognized Indian tribes in the U.S., she said, 109 of which are located in California, and eight of which are located in Humboldt County. The names of the county's largest tribes -- the Hupa, the Karuks and the Yuroks -- were not what they called themselves. Yurok and Karuk, for example, simply mean "up river" and "down river." The languages of those two tribes, Risling said, are "completely different, like Chinese and English." Nonetheless, she added, members of the two tribes intermarried and joined in certain ceremonies. Risling then began to recite a few facts. There are more than 500 federally recognized Indian tribes in the U.S., she said, 109 of which are located in California, and eight of which are located in Humboldt County. The names of the county's largest tribes -- the Hupa, the Karuks and the Yuroks -- were not what they called themselves. Yurok and Karuk, for example, simply mean "up river" and "down river." The languages of those two tribes, Risling said, are "completely different, like Chinese and English." Nonetheless, she added, members of the two tribes intermarried and joined in certain ceremonies.

While the passengers on the bus were left to wonder how that had played out in reality, George took the microphone and gestured at the snowy scenery outside. Historically and to this day, he said, "medicine people seek the high country to obtain power. If you climb one of the peaks around here," he added, "chances are you'll be standing on a powerful cultural spot for the tribes." The most powerful locations, he added, are those that afford a view of Mount Shasta, which because of its towering profile has tremendous significance for the Indians. ![[Mary Risling]](cover0321-mary.jpg) As the bus began dropping down to Willow Creek, there was -- briefly -- a lull in what was shaping up as a crash course on the past and present of Humboldt County's three largest Indian tribes: the Hupa, the Yurok and the Karuk. The tour was arranged by Two Feathers Native American Family Services, a social services agency affiliated with the Big Lagoon Rancheria north of Trinidad. The purpose of the all-day odyssey was to educate the participants -- mostly non-Indian social service workers -- about Indian culture, so that they would be better able to serve their Native American clients. As the bus began dropping down to Willow Creek, there was -- briefly -- a lull in what was shaping up as a crash course on the past and present of Humboldt County's three largest Indian tribes: the Hupa, the Yurok and the Karuk. The tour was arranged by Two Feathers Native American Family Services, a social services agency affiliated with the Big Lagoon Rancheria north of Trinidad. The purpose of the all-day odyssey was to educate the participants -- mostly non-Indian social service workers -- about Indian culture, so that they would be better able to serve their Native American clients.

Heading north on Highway 96 after leaving Willow Creek, the bus paralleled the blue-green Trinity River -- "the blood that flows through our veins," as George, a member of the Hupa tribe, described it. George, evincing that intimate connection to the land that is typical of many Native Americans, said that fish from the Trinity are unusually delicious. "I personally refuse to eat fish from anywhere else. I guess I'm spoiled." Nonetheless, he said that the river, which bisects the Hoopa reservation, is not what it used to be -- decades, much of its flow has been diverted to farmers in the Central Valley. The result has been a drastic decline in the river's once abundant salmon and steelhead runs. After years of scientific study, and much pressure from Indians and environmentalists, Bruce Babbitt, interior secretary under President Clinton, ordered two years ago that approximately half of the river's flow be sent down the Trinity. Such a redirection has been challenged in court by agriculture and hydropower interests. George told his busmates -- accurately -- that the Bush administration is so far not actively pushing Babbitt's initiative. Risling said that the unnaturally low flow in the Trinity River has had a disruptive effect on at least one Hupa ceremony -- the White Deerskin Dance, which takes place along the river and involves the use of boats. Because the dance usually occurs in late August or early September when the river is at its lowest, the Hupa typically contact the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation a few days in advance to request a release of water. Last year, which was unusually dry, the bureau did not release enough water. The result, Risling told her busmates, was near disaster -- a canoe carrying dance participants hit bottom and flipped, spilling the occupants into the water. Luckily no one was injured, but Risling said that the misadventure was interpreted at the time as an ominous sign, particularly since one of the purposes of the White Deerskin Dance is to set the world back in balance. Sure enough, Risling said, a few days later the horrific events of Sept. 11 occurred. "That was the first time in my life that a boat (used in the ceremony) had tipped over," Risling said. She said a similar incident occurred when the dance was held in the summer of 1939. That, too, was followed within days by another major disaster -- the invasion of Poland by Nazi Germany, which triggered World War II.

Hupa tribe member Merv George Jr., bares a tattoo of a pileated woodpecker. The bird has spiritual significance for his people. Hupa tribe member Merv George Jr., bares a tattoo of a pileated woodpecker. The bird has spiritual significance for his people.

The bus passed onto the Hoopa reservation, established in 1864. Shaped like a giant square, the 90,000-acre reservation is the largest in California. While armed conflicts in the mid-1800s between the Hupa Indians and American soldiers periodically forced the Hupa to leave the valley and take refuge in the surrounding mountains, the tribe was never defeated and driven off its homelands as were most other Indian tribes in California. That outcome, termed "mildly astonishing" by Edward S. Curtis, the famous photographer of early-20th century Native Americans, may have had more to do with the area's remoteness than with anything else. Regardless, it has greatly enhanced the Hupa's ability to maintain an intact culture. "A lot of tribes haven't been able to continue their ceremonies, but that's not the case here," George said. "Our ceremonies still occur where they always have, uninterrupted on some sites." The Hupa are a self-governing tribe, George continued, meaning that the tribe has its own governmental infrastructure (there are 40 separate departments). The tribe took over from the U.S. Bureau of Indian Affairs, which moved out of the Hoopa Valley in 1988. About 2,600 people live in the valley, which, at six miles long and one-to-two miles across, is one of the wider river valleys in the Klamath Mountains. As the bus passed through, George pointed out a variety of things: a grocery store; an airport; a historical village called takimildin, where the tribe has restored several traditional cedar plank houses and a sweat lodge; a collection of tribal administrative offices; a scattering of modest-looking homes built with federal assistance; a cemetery, which George referred to as the "boneyard"; an attractive three-year-old medical center; and a small casino called "Lucky Bear." It looked like a typical Indian reservation in that it had an air of impoverishment about it. And indeed, times are not good on the reservation. As the bus pulled up to a parking area, George recounted the grim statistics: the unemployment rate stands at 40 percent; 50 percent of the reservation's population is living at or below the poverty level; and the seven sawmills that used to support the tribe's timber industry -- long the mainstay of the economy -- have all been closed. ![[Byron Nelson Jr.]](cover0321-judge.jpg) The occupants of the bus pile out into the sunshine, only to be herded quickly into the tribal courthouse, where Chief Judge Byron Nelson Jr. [photo at right] explains that the court hears civil cases and that 90 percent of the caseload involves family issues such as custody disputes and domestic violence. The next stop is the tribal museum, which is small but nevertheless contains a large number of items ranging from tools from the early settlers; to ceremonial regalia such as a headdress sporting the red scalps and black beaks of pileated woodpeckers; and a striking collection of baskets (the Hupa, along with the Yuroks and Karuks, are known for their basket-weaving skills). The occupants of the bus pile out into the sunshine, only to be herded quickly into the tribal courthouse, where Chief Judge Byron Nelson Jr. [photo at right] explains that the court hears civil cases and that 90 percent of the caseload involves family issues such as custody disputes and domestic violence. The next stop is the tribal museum, which is small but nevertheless contains a large number of items ranging from tools from the early settlers; to ceremonial regalia such as a headdress sporting the red scalps and black beaks of pileated woodpeckers; and a striking collection of baskets (the Hupa, along with the Yuroks and Karuks, are known for their basket-weaving skills).

Back to the bus for a short hop over to the fire department, where inside a spacious building lunch is thankfully waiting. After 20 minutes of chatter and eating, the leader of the Hupa tribe, Clifford Lyle Marshall, [photo below left] appeared and gave a short talk. He made several points, but the one that was most striking -- and most pertinent for his audience -- was that Native Americans take a fundamentally different approach to settling domestic disputes than do whites. White society gives top priority to ensuring the safety of the victim of abuse -- as a result, wives are frequently separated from husbands through restraining orders; and children are often taken from their parents. But severing family ties "is not an option in tribal court," said Marshall, who used to be a tribal judge. "It's a peacemaker court where reconciliation through mediation" is emphasized and where both families involved are commonly brought before a judge to work out their problems. "Putting families back together is the focus," Marshall said.  Afterward, out in the sunshine, Marshall elaborated on why such an approach is better -- at least for Native Americans. "If you separate a husband and wife, whatever problems they have -- whether it's alcohol or drug abuse or whatever -- just get magnified. If you take a child away from his biological parents and move him around from foster parent to foster parent, he's going to develop `attachment deficit syndrome' where he can't develop close personal relations." Afterward, out in the sunshine, Marshall elaborated on why such an approach is better -- at least for Native Americans. "If you separate a husband and wife, whatever problems they have -- whether it's alcohol or drug abuse or whatever -- just get magnified. If you take a child away from his biological parents and move him around from foster parent to foster parent, he's going to develop `attachment deficit syndrome' where he can't develop close personal relations."

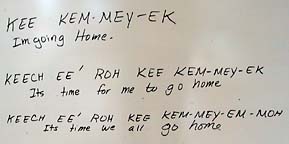

Marshall, clad in a black jacket and sporting dark glasses and a buffalo-head nickel belt buckle, has a formidable air about him. He gives the impression, as some Native Americans understandably do, that he carries inside him deep resentment against white society. When asked about how he felt about the larger society that he lives in, he said it was "exasperating at times that it's so difficult to get [whites] to understand certain things -- like recognizing that there are 540 independent nations inside the United States." He said that people frequently come onto the Hoopa reservation and behave as if the tribe has no legal jurisdiction. "People don't question it when the U.S. goes to war to protect the rights of indigenous peoples across the globe," such as "bombing Serbia to protect the Kosovars or attacking Iraq to protect the Kurds and the Shiites," Marshall said. "But when it comes to the fact that there are independent nations within the U.S., that's just too difficult to comprehend. "If there's one thing you can say about white people, it's that you can't get rid of them," Marshall added. ![[Bertha Peters]](cover0321-bertha.jpg) If Marshall had an undercurrent of anger about him, Bertha Peters manifested sorrow. [photo at right] At another stop on the tour later in the day, Peters, a middle-aged woman with an open, honest face, and Carole Lewis explained that the oral language of their tribe, the Yurok, is in danger of disappearing. Only 12 people can still speak it fluently and all of them are over 70 years of age, said Lewis, education director for the tribe. Lewis has taught herself the language, but "I can only speak it as well as a 3-year-old." If Marshall had an undercurrent of anger about him, Bertha Peters manifested sorrow. [photo at right] At another stop on the tour later in the day, Peters, a middle-aged woman with an open, honest face, and Carole Lewis explained that the oral language of their tribe, the Yurok, is in danger of disappearing. Only 12 people can still speak it fluently and all of them are over 70 years of age, said Lewis, education director for the tribe. Lewis has taught herself the language, but "I can only speak it as well as a 3-year-old."

Lewis is heartened that the language is being taught to Yurok children, who attend school on the Hoopa reservation that lies just to the south of the 56,000-acre Yurok reservation. But she is concerned that much will be lost when the older people still capable of speaking it pass away. What is most striking about Peters -- the other woman -- are three bluish-green stripes on her chin. She had them tattooed there in the 1980s. Her reason for doing so was to reaffirm her identify as a Yurok by reconnecting with an ancient tribal practice: scraping three stripes on a young woman's chin with a sharp tool. The woman's chin was then coated in soot, animal fat and pitch and eventually took on the appearance of three stripes, viewed as beauty marks and a sign of status. So far, four other women in addition to Peters have received similar tattoos. She said that when she had it done, tribal elders wanted to know why. "They were taught not to do it. It was sad for me because I realized that the old ways were all gone for my people."

Heading back to Arcata at the end of the day, the passengers on the bus watched a video on basket weaving. Much of it was about the materials that are used -- such as hazel strips and willow sticks -- and how making a basket requires a high level of dexterity and an ability to intensely concentrate for several hours at a time. But there was one section that was disturbing: Many of the women who make the baskets have fallen sick. The reason, apparently, is that they tend to collect the plants they need from roadside areas because they are relatively easy to access. Those same areas, it turns out, are routinely sprayed with herbicides so that vegetation doesn't interfere with driver visibility. Looking out the window at the fading light, one passenger, at least, reflected on how much the world has changed from the way it used to be. For thousands of years, the Yurok and the Hupa lived in what today at least seems a sort of paradise -- endless tracts of virgin forest, streams teeming with fish, abundant game, pure water. Life no doubt was short and hard, and certainly there were conflicts -- both within and between tribes. But they were free of so many of the things that plague the current era: degraded environments, disappearing wildlife, the threat of terrorism and war. What a life they must have led.

North Coast Native Lands

Sources: BIA edition 2000, California Indian Trust Land

William Bright, 1957. The Karok Lanugage. UCPL 13.,

www.snowcrest.net/sandspit/maptboundaries.html,

Angie Weaver,

Llewellyn Loud, Ethnogeography and Archeology of the Wiyot Territory,

1918 UCPA AE 14:3,

T.T. Waterman. 1920. Yurok Geography. University

of California Publication in Archeology and Ethnology. 16:5.

Ruth Bennet, Ethnographer Center for Indian Community Development

IN THE NEWS | PUBLISHER | CALENDAR Comments? E-mail the Journal: [email protected]

© Copyright 2002, North Coast Journal, Inc. |