|

IN THE NEWS | CALENDAR

by KEITH EASTHOUSE

FOR BRIAN WILLSON, THERE IS NO INTERRUPTION. There was the press conference and the spiritual service that he and the other protesters held about 90 minutes beforehand. And then there was the hospital room he woke up in five days later, the room crowded with large green plants and brightly colored flowers. That's it, just two disjunct events, nothing between them, no memory or even the shadow of memory. A black gap -- or a black hole rather, a vortex inside himself that sucked in what happened and annihilated it. The mind protecting itself. That's one explanation. The other is simply that his head was banged around so hard that his brain couldn't process the memories -- time destroyed by blunt trauma. That's the version favored by the doctors, who early on assured Willson that the moment would always remain blank. Whatever the cause, it appears that, more than 15 years later, Willson is free of any tortured recollections. He doesn't remember sitting on the tracks, Buddhist style, with six other anti-war protesters at the Concord Naval Weapons Station on Sept. 1, 1987. He doesn't remember the bright, noonday sun. He doesn't remember the dark of the approaching munitions train, its metallic screech, the mad scramble at the last second to get out of the way. He doesn't see himself getting pulled under and "tossed back and forth like a rag doll" beneath the wheels, as one observer -- the woman who was then his wife -- would later describe it. All of that -- and worse -- is gone. The episode hurt him terribly, but just once. It evidently can't come back.

Sept. 1, 1987: Brian Willson tries too late to get out of the way.

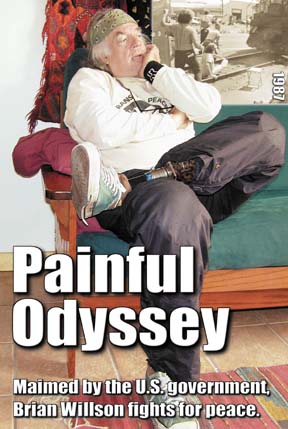

Slipping into Arcata He opened the door, a big, burly aging hippie. Gray hair kept in check by a pale green bandanna wrapped about his head. Long black baggy pants. A somewhat stiff-legged gait. When he sat down on a couch and crossed his legs, the poles that plunged into his Converse tennis shoes became visible. It was disconcerting to see, skeletal in an artificial way, a body -- or body part -- composed not of flesh and blood but of metal and plastic. Up high on a wall was a painting of train tracks, purplish and yellow. Near it was a strange and somewhat crude series of drawings of dark figures in different postures juxtaposed against more train tracks.  Willson's bulging, watery brown eyes make him seem oddly vulnerable, almost puppy-like. But his stature (he's 6-2), the obvious physical strength of his upper body and the dignity conferred by age (he's 61) all give him an imposing air. He's not overbearing and strident, as so many activists are. Instead, he's persistent in a soft-spoken sort of way, inviting you to see things from his point of view but not demanding that you do so. There's a detachment about him; he speaks his piece, but then he moves on. Willson's bulging, watery brown eyes make him seem oddly vulnerable, almost puppy-like. But his stature (he's 6-2), the obvious physical strength of his upper body and the dignity conferred by age (he's 61) all give him an imposing air. He's not overbearing and strident, as so many activists are. Instead, he's persistent in a soft-spoken sort of way, inviting you to see things from his point of view but not demanding that you do so. There's a detachment about him; he speaks his piece, but then he moves on.

Willson quietly slipped into Arcata about a year ago, buying a house in the Arcata Bottoms -- a house that a new acquaintance, building contractor David Meserve, subsequently worked on. The two had met in October 2001, when Willson came up from his home in Santa Cruz to speak at a gathering organized by Meserve's group, the Redwood Peace and Justice Center. Willson liked the area; it reminded him of the small farming community in western New York where he'd grown up. It was politically progressive -- Arcata, that is -- a university town "and far enough from the Bay Area to keep people away." A galvanizing force But while Willson has kept a low profile, he has not been a hermit. He has testified at Arcata City Council meetings, such as the one last fall where he expressed support for a proclamation opposing war with Iraq; he has come out publicly in opposition to the U.S. Patriot Act, which he thinks is unconstitutional; and he's a regular at the Friday afternoon peace vigils on the Plaza, standing on the southwest corner with members of Veterans for Peace, a group he initially joined years ago. It's as a member of that group that Willson, an energetic, even restless man, has mostly made his mark locally. According to Meserve, now a member of the Arcata City Council, Willson has galvanized Veterans for Peace and made it "one of the most active peace groups" in Humboldt County. [photo below left: Veterans for Peace at the weekly Friday afternoon vigil on the Arcata Plaza.]  For several months the group has been quietly lobbying the Northern Humboldt Union High School District for permission to come onto the campuses of Arcata and McKinleyville high schools to stage "counter-recruiting" presentations. The idea is to give the kids a different view of the military, and of war, than the one offered by military recruiters. For several months the group has been quietly lobbying the Northern Humboldt Union High School District for permission to come onto the campuses of Arcata and McKinleyville high schools to stage "counter-recruiting" presentations. The idea is to give the kids a different view of the military, and of war, than the one offered by military recruiters.

Willson said counter-recruiting is particulalry important now because of the looming war in Iraq and because President Bush's No Child Left Behind act mandated that high schools provide recruiters with the names, addresses and phone numbers of all their students -- not exactly a level playing field. In essence, Willson said, the group wants to warn students about what they could be getting into. "There's a good chance they could wind up killing civilians and having to live with that for the rest of their lives." The group has been invited to speak to high school students in the past -- for example, last month at Arcata High -- but has not been granted the same status as military recruiters. The discussions to change that began in November when a meeting was held with Kenny Richards, superintendent of the district. But then, for unclear reasons, things bogged down -- a fact that frustrated not only the group, but also Meserve. In one letter in January the veterans went so far as to threaten a lawsuit, pointing out that a 1986 federal appeals court ruling found that a school board in Southern California had violated the First Amendment when it refused to give a peace group the same access enjoyed by military recruiters. Evidently, that got Richard's attention. Last week, he informed Veterans for Peace that it was free to contact the principals of the two schools about getting "added to the classroom speaker list" and to discuss giving "library presentations" to larger groups of students. Bob Wallace, principal of Arcata High, said the counter-recruiters would be treated the same as the military recruiters. Richards also dropped his demand that members of the group be fingerprinted, a standard screening procedure aimed at detecting child molesters and other criminals. As both Willson and Bill Thompson, another member of the group, pointed out, veterans have already been fingerprinted. They also didn't see the point since the group was only going to be addressing students in groups, not one-on-one. "It just didn't feel right," Willson said of the fingerprint demand.  Arcata High School students during a recent anti-war protest. Veterans for Peace wants students to know about the horrors of war. Arcata High School students during a recent anti-war protest. Veterans for Peace wants students to know about the horrors of war.

A `quiet loud action' Given what happened to him, Willson can be forgiven if he seems a bit paranoid. Back at his home, sitting on the couch, he talked of the "assault," as he calls his collision with the train, how he learned afterward that the federal government had him on a "domestic terror watch list" -- evidently because he was a relatively high-profile peace activist -- and that the train's crew had been ordered not to stop for fear that he and the other protesters would storm the train and seize it. Blockades, he related, were routine at the weapons station, which was shipping arms to U.S.-backed forces in Central America like the Contras, and trains had always stopped before. He was 46 at the time, a trained, although not practicing, attorney and a veteran protester -- he had engaged in a 36-day fast in front of the U.S. Capitol in 1986 and was about to begin a 40-day "Fast for Life and Peace" outside the naval facility. But it was the first time he had put himself in harm's way to stop a weapons shipment. The silence of the act appealed to him. "I don't like to shout," he explained. "I like quiet loud actions."  Little did he know how loudly this particular action would reverberate. It made him an instant celebrity, the activist whose legs were severed -- below the knees -- by a military train. Front page news everywhere, the clip of him struggling to rise from the tracks as the train bore down on him played over and over again on television. Little did he know how loudly this particular action would reverberate. It made him an instant celebrity, the activist whose legs were severed -- below the knees -- by a military train. Front page news everywhere, the clip of him struggling to rise from the tracks as the train bore down on him played over and over again on television.

It was a long recovery; he was in the hospital for 28 days and of course there were follow-up surgeries. But he was much in demand as a speaker and went on tour for months at a time, sometimes "doing five gigs a day." He gave talks -- most of which were paid -- to "all kinds of organizations: church groups, civic groups, peace groups, veterans groups. A lot of university speaking. Even high schools." His message was always anti-war, and, to some, offensively anti-American -- made more so by the fact that at one point he had a well-publicized meeting with Sandanista leader Daniel Ortega. Once, when he gave a talk at a high school in Concord, not far from where he was run over, he was hustled off the stage due to a bomb threat. "I guess some people considered me to be some kind of threat. I don't know. It was always a mystery to me." He recalled another time when, in conjunction with one of his talks, the local paper ran an editorial that blasted him for meeting with Ortega. [photo above right: Willson talks about his Vietnam experience at the D Street Neighborhood Center last week. ] A costly triumph In the midst of this period, in November 1990 to be exact, Willson had a triumph when the federal government agreed to settle the lawsuit he and four other demonstrators had brought against the U.S. Navy over the train incident. The payment was a whopping $920,000, about $800,000 of which went to Willson. Strictly speaking, it was not a legal victory as none of the defendants -- the U.S. government, the three-member train crew, two supervisors at the Concord base -- formally admitted legal responsibility. But as one of Willson's attorneys said at the time, "You don't pay out close to a million dollars without being at fault." The Navy's case was weakened by several factors. Shortly after the incident, officials at the base maintained that the train crew had been surprised by the protesters. Subsequent investigation revealed that the crew was aware of plans for a sit-down demonstration that day, that they had a clear view of the demonstration 600 feet down the track and needed only 143 feet to stop. Additionally, while it was initially claimed that the locomotive had been traveling at 5 miles per hour, as required by base regulations, it turned out that the actual speed was as high as 17 mph. Finally, during depositions it came out that one supervisor had told the train conductor that there would be a confrontation with demonstrators "sooner or later, so we might as well have it now." Navy officials denied that there was any intent to harm the protesters. Nonetheless, two months after the incident, disciplinary letters were put in the personnel files of Capt. Lonnie Cagle and Cmdr. Clayton Y.K. Ching, the installation's two top officers, for failure to assure safe operations. Fortunately, Willson's share of the settlement was not eaten up by medical bills, which totaled about $150,000 (in addition to losing his legs, he's got a metal plate in his head, inserted there after a piece of his skull was driven into his brain during the thrashing by the train). Those expenses were covered, and then some, by an incredible outpouring of $250,000 in unsolicited contributions that came in during the weeks after he was injured. On the downside, half of his share of the settlement -- $400,000 -- went to his lawyers. He put what remained into a trust, "with trustees technically controlling the money. I am able to draw on the interest. The rate of return is not that high. But it gives me a bottom-line security." The first trauma Until you understand that Willson remembers nothing of the train rolling over him, it seems odd that another event -- something that happened to him in Vietnam -- should carry more emotional weight. The year was 1969 and Willson, a 29-year-old Air Force lieutenant, had just arrived for his tour of duty. He was sent out with a South Vietnamese officer to inspect villages that were supposed to have been bombed. "We were double checking on the South Vietnamese pilots. There was a rumor that they were missing their targets intentionally." It wasn't true, which became plain in the first village they went to. The first thing Willson noticed was that everything was destroyed. The second thing was a water buffalo. "It had a three-foot gash in its belly and it was uttering these loud roars of pain." Willson shifted his eyes and saw something far more shocking: a pile of corpses, including, down near his feet, a woman holding her three children in her arms. At first he thought they were alive; but then he bent down to look and saw that they had been burned by napalm. Willson gagged and then started to cry. The South Vietnamese officer asked him what was wrong. With effort, Willson replied: "This is my family." "It was a shift in my consciousness," Willson recalled, saying that he suddenly saw the connection between himself and the dead people all around him: They were all human. More slowly, he began to question what his country was up to. At first he thought the bombing of this particular village had been a mistake, an intelligence screw-up. But then he saw similar horrors in other villages. "I had believed in the fantasy of American history," the notion that America, despite its flaws, was fundamentally a good country, Willson said. He wasn't long in Vietnam before that belief began to unravel. What outraged him was that the American military, in conjunction with its South Vietnamese allies, was hitting civilian targets; most of the dead bodies that he saw belonged to children, women and the elderly. Not only was it morally wrong, he believed it was a war crime, a violation of the international restrictions that had been placed on targeting civilians after World War II. Willson became a pacifist, which completely changed his outlook. "I was disgusted with everything I saw in Vietnam. I was having all these epiphanies, but I had no one to talk to." When he left Vietnam, he was "glad to get the hell out of there." But, like many Vietnam veterans, he found that he couldn't truly escape what he had experienced. "Seeing a lot of dead people affects you. It leaves a psychic scar."  Brian Willson on his preferred mode of transportation, a 14-gear, hand-powered tricycle. Brian Willson on his preferred mode of transportation, a 14-gear, hand-powered tricycle.

Uncomfortable with the flag Given his reaction to Vietnam, it shouldn't be surprising that the American flag is not his favorite symbol. That became apparent during the speaking gig in Arcata where he met Meserve. It was a month after the terrorist attacks, and the speaker before Willson had talked about the need for peace advocates and others on the left to reclaim the American flag from conservatives. When it was Willson's turn to speak, he immediately told his audience that he was uncomfortable sharing the stage with the flag -- a pretty gutsy thing considering how many people at the time saw the expression of patriotism as a way to honor the 3,000-plus people killed in New York and Washington, D.C. Meserve, who was doing sound for the event, quickly came to Willson's rescue. "He said something about how he couldn't speak next to the flag, so I went up there and took it away," Meserve recalled. The flag was also an issue at the monthly meeting of the Veterans for Peace group last week. The group is going to be marching in the Eureka peace march scheduled for this Saturday, and the question was whether the vets should carry the American flag. The ultimate decision was not to. "I think we should carry an Earth flag or something," said Willson, who is slated to speak at the end of the march. Feeling edgy On an emotional level, Willson has been going through a tough phase lately. He doesn't know whether it's all the talk of war with Iraq or what, but he's been having more panic attacks than normal (such attacks, which he believes are related to his Vietnam experience, have long been with him). It might also have something to do with what to him -- and many others -- is the Orwellian emphasis on homeland security that has swept the country since Sept. 11, raising concerns about diminishing civil liberties. Given that he was branded a terrorist during a previous Republican administration (that of Ronald Reagan), Willson has more reason than most to be, to borrow a phrase from the `60s, freaked out. "It's a frightening era," Willson said. It's hard not to wonder whether the root cause of his anxiety isn't what happened to him on the tracks. But he seems to be, if not at peace, at least safely separated from that. "I was doing what I believed in on the tracks. I wasn't in conflict with myself." He paused, suddenly turning those pleading eyes on his questioner. "But it's not like it's been real easy."

IN THE NEWS | CALENDAR Comments? E-mail the Journal

© Copyright 2003, North Coast Journal, Inc. |