|

by ANDREW EDWARDS Independent observers largely unusedby KEITH EASTHOUSE and ANDREW EDWARDS On the cell with 'Remedy'Interview & photo by BOB DORAN by ANDREW EDWARDS GRAB. PULL AND STAND UP. MOVE THE LEAD PRESSURE KNOT, near your midsection, up the cord. Lean back into the harness. Steady yourself with your left foot against the tree. Try not to twirl. Try not to freak out. Grab the lower knot, the one attached to the strap around your right foot. Loosen it. Inch the knot a little farther up the line. Grab. Pull and stand up. Repeat. Rope climbing up to a tree-sit

the first time -- the first few times, no doubt -- is awkward.

It's tedious. It's strenuous. It's like climbing 10 flights of

stairs with one foot while dangling off a cliff. You think that you're never going to get there. My unflappable climbing instructor, "Annapurna," had told me during our brief training course that it takes experienced climbers 15 minutes to reach a platform, about 10 feet per minute. I was working on 30 minutes and I wasn't even close yet. Anna busied herself on the forest floor beneath me. I'd catch glimpses of her sitting on a stump, grubbing through a bag of nuts a well-wisher had left with her, scraping fresh orange spray paint off the base of the tree, all between heaves up the line. [A tree-sit in the Lower Village. Photo courtesy of wesavetrees.org] The gaps between heaves got longer as I ascended. I'd pause to look at the view, rest, stare at my hands. I had forgotten gloves. With each successive pull the rope chafed them. First blisters developed. Then stigmata of the tree-climber: sores shining pink, red and moist on the pad of the middle finger and below the first knuckle of the index. The platform loomed above. Below, people had turned into indistinguishable, yelling dots. What worried me (I don't have an inordinate fear of heights) wasn't the empty air beneath my feet, but the fact that the narrowing tree trunk, slicked from many ascents, was beginning to offer poor footing. I felt as if I could slip off either side and go swirling into the afternoon sky. Irrational? Yes. But the fear was definitely real. I reached the first branches.

Solid ground, sort of. Then the first platform, a simple 2 x

6 plywood affair with a huge bucket of what I was to learn was

concrete secured at its center. More branches, and finally, the

platform. There is no final dash I poked my head above deck and

looked around. I think someone offered me a hand and hoisted

me up onto the platform, but I'm not sure. I was laughing. Looking

at my hands [see photo

at left by Annapurna] where the

sores had turned black from rubbing on rope. I kept laughing

as I rubbed hydrogen peroxide on them. They bubbled white. It

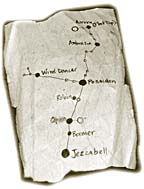

hurt like hell. There were only three tree-sitters up Poseidon (named for its ocean view) when I arrived; many people had not yet returned from supply trips to town. This tree is part of what is collectively known as the Lower Village (the Upper Village houses long time tree-sitters Remedy and Wren). Twenty-two trees in the Lower Village are connected by rope traverses that allow for air travel between them. There are eight platforms, all of them occupied. On a given night anywhere from eight to 20 activists may be sleeping up there. As many as six have slept on just the one platform I was on. Right now it is the largest tree-sit -- both in terms of numbers of people and numbers of trees -- in Humboldt County, placing it in the running worldwide. [Map of the Lower Village in Freshwater.]

Imitating JuliaThe two tree-sitting villages

in Freshwater, a heavily logged watershed northeast of Eureka

owned by the Pacific Lumber Co., would probably not be there

at all were it not for Julia Butterfly Hill, who at the age of

23 ascended Luna, a redwood near Stafford, on Dec. 10, 1997.

Butterfly, as she initially called herself, didn't invent tree-sitting;

others had climbed trees before that they didn't want cut. What

was remarkable was how long she stayed -- two years -- and the

extent to which she was able to attract the attention of the

media. Her effectiveness did not simply mean, when she climbed down on Dec. 18, 1999, that she had made a good career move. It also meant that her fellow logging activists had an audacious new weapon at their disposal -- occupying trees marked for cutting. It was, and is, a risky business. Last October, a 24-year-old tree sitter named Robert Bryan fell 85 feet to his death from a redwood in the Santa Cruz mountains. Bryan, known as Naya, was alone at the time and the exact circumstances of his fatal plunge are a mystery, although no foul play is suspected. In April of last year, Beth O'Brien, 22, died after falling 150 feet during a logging protest on the Mt. Hood National Forest in Oregon. She had unhooked herself from one tree-sitting platform and was trying to reach another by a rope ladder when she fell. [Julia Butterfly Hill, in Luna, 1998. Photo by Eric Slomanson.] A spate of tree-sitsThere have no deaths or serious

injuries among tree-sitters on the North Coast -- rather surprising

given the scale of the arboreal protests that have been going

on lately on Pacific Lumber land. But as most tree-sitters know,

blood has been spilled -- in September 1998, when David "Gypsy"

Chain was crushed to death by a falling redwood on PL land near

Grizzly Creek Redwoods State Park (PL officials maintained that

Chain's death was an accident, but Earth First! said the tree

was deliberate Chain, who was 24, was not a tree-sitter, but to those who are, Chain is an icon, someone who paid the ultimate price in defense of the forest. The chances of an accident -- or an incident -- appear to be on the rise as protestors have been taking to the trees in record numbers in recent months. The trigger for the latest round of activity was an August court order by visiting Superior Court Judge John Golden that protestors read as requiring a halt to logging on Pacific Lumber lands. The judge made his ruling after the California Department of Forestry failed to turn over thousands of logging-related documents. The company continued cutting in the face of the order, arguing that it did not apply to already-approved logging operations -- a position that seemed vindicated in December when Golden essentially negated his earlier ruling and exempted 100 timber harvest plans to avoid causing undue "economic hardship" to the company. But the spate of tree-sits the whole affair produced continues to this day. Also pending are several trespassing cases against tree-sitters brought down by Pacific Lumber's tree-climber, Eric Schatz. Schatz went up after tree-sitters on 15 occasions last year, bringing down people eight times.

[at left, a hammock tree-sit] Another protestor pulled down from a tree, Jamie LeRoy Harris, hit back after being cited for trespassing. He is charging Schatz, Carl Anderson, head of PL security, and Robert Manne, president of the company, with assault and intentional infliction of emotional distress, among other things. (Harris' case, which is pending, is being handled by Tony Serra, who successfully represented Darryl Cherney and the estate of Judi Bari in their landmark civil rights lawsuit against the FBI and the Oakland Police Department). Unfazed by the riskThe possibility of arrest didn't seem to be on the minds of the tree-sitters I found myself with on the platform. To my right was Wren, 26, sitting silently in a beanie, a sweatshirt and pants, her legs stretched out in front of her. She is a small, plump woman (contrary to popular belief, tree-sitters don't waste away; in fact, the Lower Village's recruitment web site, wesavetrees.org, warns that tree-sitters are likely to gain weight) with a sad face and a thousand-yard stare. I asked her what she was doing

down from her usual perch in the Upper Village, about a half-mile

farther up Greenwood Heights Road. She said she was just visiting

for the company, something she'd been doing fo

[left, Lodge Pole offers food with Nudie in foreground. right above, inside a tree-sit; below, bus bench in Poseidon. Photos courtesy wesavetrees.org] Wren, like many of the sitters,

is originally from the East Coast. She was working as the editor

for a small paper in New Jersey when she flew out to the West

Coast. She arrived in San Francisco last May, drove up to Humboldt

County, and has been up a t To my left was Nudie, a jittery, if cheery, 24-year-old man with a full red beard, a wool cap and glasses. This was his first climb. He showed me wounded hands similar to mine, and giggled a little. From Chicago, he had a thick accent. He was given the moniker after pulling his pants down -- and leaving them there -- during a recent protest in Berkeley. Cooking up some food on a gas stove was one of the group's leaders (though they don't like to be called that), Lodge Pole, who is 23. LP, as he's also known, initially moved to Humboldt County at the age of 17, ostensibly to be an activist. At first he lived homeless on the streets of Arcata, at times selling pot on the Plaza to support himself. One of his first "forest actions" was cleaning up after less environmentally conscious homeless people while camping out in the Arcata Community Forest.

"I have a very hard time working with him; I refuse to do actions with him," said one tree-sitter, who asked that their name not be used. "Frankly I think he's abusive." [ A traverse in action] When asked for his perspective, LP said: "It's a high-stress job. Basically, I think a lot of people don't take what we're doing nearly as seriously as I do." Personality aside, LP does seem to get things done. That food, for example. It was a burrito full of eggs and vegetables, which, happily, he offered me. Briefly, he posed for a picture with his creation. Then he handed it to be and I wolfed it down. More impressively, LP and a thin bearded activist known as The Dude, basically built the village beginning last fall, around the time of the Earth First!-organized 13 women for 13 days in 13 trees sit, which kicked off a lot of the action going on now. Anna, for instance, was one of the 13 women, occupying a tree in Freshwater after doing resupply work in the Mattole for two weeks. She came out there directly after graduating from Parson's School of Design in New York with a bachelor's in photography. First they built a single platform, then they thought big, dreaming of creating a city in the trees. And now, nearly six months later, their dream has become a reality. Their group is not officially affiliated with Earth First! proper, preferring to identify themselves as "forest defenders" or simply "people who save trees." The Poseidon platform is a 15-foot-wide donut of scavenged plywood completely covered in a yurt-like ceiling of overlapping tarps. Hung inside are jugs and buckets of supplies, water, juice, eggs, nuts. The supplies come mainly from their table in front of the Arcata Co-op, but donations come in from a variety of sources, including their website. Then there is the bathroom bucket and the piss jugs (women use a funnel). "All except Lemur," LP chimed in. "She can do it without spilling a drop." On the platform, people read, play music, write, take pictures, plan, hold meetings, sleep, cook, talk: whatever it takes to while away a day. It's supported by several large branches and a whole series of ropes stretching down in triangular formations curiously resembling a sailing ship's rigging. According to LP the rigged nature of the platform is the reason pirate yells are so popular between the trees. It's like they're in a crow's nest. "Arrrg! Ahoy! Avast ye!" LP yells out with the appropriate accent in response to a call from a nearby tree. "We're tree pirates," he explained. A lot of yelling goes on, between trees and between the trees and the ground. One of the tree-sitters' first responses when they see someone on the road is to howl and hoot. If the call is returned, they know it's a fellow activist. There are other calls from the ground. Most people just pass by. Some honk support. Some have something to say. "Trespassers should be shot!" one obviously irate woman yelled up at the tree while I was in it. "Be sure to get this down," LP said. "We think she's crazy." "We love you!" all the tree-sitters yelled back. Sometimes, however, the threats are more serious. Most obviously, there's the height. "The fall, I understand, probably is not that bad; it's the landing that can kill ya," quipped new District Attorney Paul Gallegos in an interview several weeks ago. If you fall from 130 feet up you will probably die. At the very least you're going to be turning your skeleton into a shattered wreck. But when you're in the tree the ground looks so far away that even the memory of it seems strange. Mostly it's obscured by the view of surrounding limbs, which makes things easier. Some tree-sitters, as Nudie confessed to me, are deathly afraid of heights. They try not to look down. A nasty encounterOther, more pragmatic concerns await them on the ground: Pacific Lumber Company security and Humboldt County law enforcement. When PL security gets involved the punishment can become of a more corporal nature. Last Saturday, the Journal ran right into the thick of a confrontation. Several sheriff's trucks were parked at the side of the road. Deputies were yelling up into the trees. A supporter on the ground, Meighan O'Brien, and several neighbors, looked on. In a white pickup truck sat a stocky man, Bradley Thrasher, 38 of Eureka. He sported dark sunglasses, a thick mustache and was wearing an Initial Security uniform and cap. He was taking pictures of everyone who passed by. Here, it was clear, was a PL-hired security guard. Apparently what had happened

just minutes before was this. O'Brien had come up to the tree-sitters

to give them some dried mangoes. She is new to Humboldt and almost

worships the young defenders. Bear, 26, [photo at left] a

new "I'm actually starting to climb the tree," Bear said in an interview later by cell phone. "He comes around the left side of the tree and pulls out his Gerber [a sharp easily retractable knife], flips out the blade. So I start trying to go up more to keep him from cutting it." They both grabbed the rope back and forth, struggling. And then the guard struck. Thrasher slashed with his knife, severing the half-inch woven rope and cutting a more than two-inch gash across the palm of Bear's hand. "Never happened," the guard muttered as the story was related to me by O'Brien, 5 feet from his truck window. As the investigating officer, Deputy Mike Fridley, took him over for identification and citizen's arrest by Bear, Thrasher told Fridley that Bear must have done it to himself. Deputies cited him for assault and battery and advised him to leave the area. He was back the next day patrolling up and down Greenwood Heights, and, according to activists, miming shooting at them as he drove by. Overall the heat is on. Every

tree-sit has had a number spray-painted at its base, often along

with the names of known occupants. According to their website,

they usually know a climber is coming, because it'll be right

after a timber harvest plan is approved. Since the North Coast

Regional Water Quality Control Board granted P They're prepared. They've got a cement-lined, 600-pound lock box [ photo at left] on one platform and others scattered elsewhere. The boxes are two welded cuffs that a tree-sitter locks their hands into, after wrapping their arms around a tree trunk or a limb. They also have a network of area residents who are ready to come out in case of an incident, to at least bear witness. The risk doesn't stop people from coming, though. When I was there, person after person came up through the hole in the deck. There was Huckleberry (Finn), Lemur, Oak, Bard, Tadger, Charity, and Annapurna, who came up soon after me. Soon there were so many we had to stand on branches, so as to take weight off the platform. [Mike fridley, of the Sheriff's Department on left, with Bardley Thrasher, a PL security guard.] Time to go downNight fell. From under a flap I watched the glittering lights of Eureka turn on, across the valley. It was time to go. Down. There was only one way. I had to rappel down, and without someone on the other end controlling my rate of descent. Huckleberry talked me through it as we stood over the little black portal that led 130 feet down to the forest floor. He showed me how to run rope through a figure eight device that allowed me to control my fall, and how to loosely hold my safety knot so it didn't tighten up and leave me dangling. I was obviously nervous. The

Grateful Dead were wailing out a rambling caterwaul of a bluegrass

tune on some live bootleg CD that blared out of the tiny silver

radio. Someone turned it off. I leaned back into the rope, holding it in the sleeve of my fleece shirt, so it didn't burn a hole through my hand as I went down. I couldn't help looking down. Someone started singing, to the tune of the old Willie Nelson song. "On the rope again, "Just can't wait to be on the rope again. "The life I love is building tree-sits with my friends, "And I just can't wait to be on the rope again." I shoved off, feeding line out until the figure eight burned with heat. It was black. Just the tree and my feet shoving off it in the light of a borrowed headlamp. And then, before I knew it, I was on the ground. I stood up, exhilarated, whooping. "Are you all right?" I heard a voice yell from above. I felt great. Editor Keith Easthouse and staff writer Bob Doran contributed to this report. Independent observers largely unusedby KEITH EASTHOUSE and ANDREW EDWARDS In a dim green-gray blur beyond a veil of mist, one could barely make out the triangle of tarps and three-millimeter cord that Molly had woven 150-feet up the redwood tree she had moved into three days before. "I feel like spider woman," she yelled down at the men below her; you could almost see the smile she was hollering with. They were two older men, one, Erich Schimps, dressed like the Humboldt State University librarian he used to be; the other, Roger Zoss, sporting the beanie, flannel and blue jeans of the commercial fisherman he once was. Schimps and Zoss belong to the Independent Observers Project, and they were out on this muddy logging road last month to get a fix on Molly's location. Just in case. There are about a dozen independent

observers, and even though they could be a calming force in confrontations

between loggers and protestors, they remain an underutilized

resource (At the request of the American Civil Liberties Union,

however, they are going to monitor a peace march in Eureka March

15). The push to have independent observers came after the death of David "Gypsy" Chain, a 24-year-old activist who was crushed to death by a falling redwood in September 1998 (PL said the tragedy, which took place on PL land in the Van Duzen watershed, was an accident, while Earth First! insisted that a logger had deliberately sent the tree at Chain). [Observers Erich Schimps and Roger Zoss near a tree-sit on Kneeland Road.] The idea was simple: field a team of people not to mediate disputes out in the woods, but to simply watch them. Schimps explained it this way: "We are basically here to observe what actually occurs in as objective a manner as is humanly possible. It's valuable because it puts everybody on their best behavior, including law enforcement and the demonstrators and Pacific Lumber. "It's a proven fact that when you have a neutral party witnessing any event the participants are normally aware of it and act accordingly," Schimps went on. "It helps to neutralize potential violent scenarios." The independent observer concept is not unique to Humboldt. Many major university campuses, for example, use independent observers to monitor student protests. Independent observers were also on hand at the 2000 Democratic convention in Los Angeles. The independent observer movement in Humboldt went swimmingly at first, as the county Human Rights Commission recommended that the Board of Supervisors endorse the idea. But the board balked after county legal staff raised concerns about liability issues: if one of the observers were hurt in the line of duty, the county could be vulnerable to a lawsuit. Deprived of the imprimatur of the county, the movement languished. It has taken on new life in recent months as an increasing number of tree-sits has raised the likelihood of violent confrontations out in the woods. One positive development for the observers is that, due to some changes in the law, the liability issue is not as pressing a concern for the county as it once was, at least according to Supervisor John Woolley. Last month, the county agreed to pay an expert from the University of Oregon to come down to Humboldt and provide training. Finally, the new district attorney, Paul Gallegos, has indicated that he would not be inclined to prosecute independent observers were they arrested for trespassing on PL property. Independent observers "don't fall under what we generally prosecute as criminal trespassing which is that someone is there to basically disrupt lawful business activity," Gallegos said recently. Trespassing in and of itself is a violation, but whether [this] rises to the level of a criminal trespass, I doubt it." PL, however, appears to be opposed to letting independent observers onto its property. At least, that's Schimps interpretation. "We've tried to meet with PL. We've sent e-mails, letters, made telephone calls. We've never gotten a response." The independent observers have been unable to get something else: a firm agreement from the county Sheriff's Department to notify them ahead of time so that they can be on hand when an enforcement action occurs. Both Zoss and Schimps said they have talked with the new sheriff, Gary Philp, and that he has been cordial, but non-committal. Philp said his hands are tied as long as Pacific Lumber refuses to give the independent observers permission to enter its property. "It's not my decision. It's only that [of] the private property owner. We can't let them on [without] the owner's permission." The bottom line, then, is that the independent observers are still out in the cold. Which is frustrating for Schimps and Zoss, who see a disturbing cycle getting set up: as more people take to the trees in protest, Pacific Lumber, in turn, is more frequently sending a climber up after them. "Most people up in trees have developed a relationship with the tree to point where they won't let that tree be taken down, even if it means risking their lives," explained Schimps. "They have in their own minds a contingency plan in case a climber comes up, and it's to go to the highest point in that tree where a climber may not be able to reach them." Two individuals grappling 200 feet or more up a redwood tree or even just 20 feet up is obviously a dangerous situation. Which is why Schimps and Zoss believe Pacific Lumber, in using climbers, is violating its own internal guidelines. They point to a Sept. 1, 2002 memo by president Robert Manne that directs all company employees and contractors to avoid "a physical or verbal confrontation" with a trespasser. Company spokeswoman Mary Bullwinkel made that memo available to the Journal, as well as a "bulletin" last spring in which Manne told his workers that "PALCO respects and will do everything in its power to protect life -- our employees, law enforcement personnel, the public and environmental protestors." Bullwinkel, when asked about the company's view of tree-sitters, said "Our position is that tree-sits are illegal and dangerous activities." But Schimps said there's more to the story than that. He said the trespassing wouldn't be happening if Pacific Lumber were logging at a sustainable rate. "My sense is that the tree-sitters and the protestors in general have a case because the contrast between present day PL and traditional PL before [the mid-1980s takeover by] Maxxam [PL's parent corporation] is so radical. Just take a trip up Kneeland Road and you'll see industrial logging comparable to what went on in the `40s, `50s and `60s. "A lot of acreage," he added, "is simply getting devastated." On the cell with 'Remedy'interview & photo by BOB DORAN THE 200-FOOT-TALL REDWOOD REMEDY CALLS home is emblazoned with graffiti. The tree's name, Jerry, and hers were painted on the trunk by representatives from Pacific Lumber, the company that owns the tree -- and, as Remedy pointed out, most of the Freshwater watershed. The 28-year-old woman lives

on a makeshift platform 130 feet up the tree, not far from Greenwood

Heights Road. Jerry (a moniker chosen by another activist in

honor of the late rock legend Jerry Garcia) stands in the "Upper

Village," a collection of four tree-top platforms on the

edge of a proposed clear-cut officially known as Timber Born and raised in Michigan, Remedy hit the road after high school, eventually settling in Olympia, Wash. Living near the rainforests of the Olympic Peninsula, she grew to love the woods and learned something about the battle over the remaining old-growth forests. ['Remedy' dangles on a rope tethered to her Freshwater home, a tree named Jerry. Photo by Bob Doran.] Before coming to Humboldt County she was working in a bookstore, dabbling in astrology on the side. When vacation time came around in the summer of 2001 she decided to volunteer helping the activists who were trying to stave off logging in the Mattole watershed. The action was hot and heavy when she got there: People were barricading roads, getting thrown in jail. The self-described "never-been-arrested middle-class girl" stayed out of trouble. Due back at work on Sept. 12, she changed her mind about returning once the Sept. 11 terrorist attacks happened. "I felt like I needed to do something. There are so many problems in the world. I picked this one," she said. She decided to become a full time "forest defender." The conversation below took place last week via cell phone, Remedy's lifeline to the outside world. She's on it all day calling a wide range of people: her mother back in Michigan, general supporters, representatives of local environmental groups. To talk to fellow tree-sitters in the "Lower Village," located nearby in a different cutting unit, she uses a more primitive communications device: a walkie-talkie. She talks often with reporters. In recent weeks she's been on the line with a CBS reporter from Los Angeles and with a Ladies' Home Journal correspondent, who asked about her housekeeping. She said she's willing to put up with questions about cooking or the lack of showers, as long as she can squeeze in her opinions on topics like clear-cutting and the importance of old growth trees. She uses the platform she lives on, in other words, as a platform for her strongly held opinions. While she's been getting some media attention, it pales in comparison to the notice Julia Butterfly Hill -- the world's most famous tree-sitter -- enjoyed during her two-year occupation of Luna, a redwood near Stafford. The novelty, evidently, has worn off. --- How long has your tree been occupied? Was there someone there before you? The first time I saw this tree I was just compelled to climb, I don't know how else to describe it. The first person sat up here for a night or two, then I came up and sat for about four days. Then I went back down to the ground. [At that point] the question I was asking myself was `What do I do? What is the most effective thing that I, personally, can do?' All indications were that I should sit in this tree, so after being on the ground for five days I came back up. That was March 21 last year. My feet haven't touched the ground since. That must be hard. Living in a tree is hard work. It's really special and amazing -- and by far the coolest thing I've ever done -- but it's not easy. Do you ever feel like you're in solitary confinement? I do. And at times I've used that analysis to understand the fact that I can do this. There are people who really are in solitary confinement, and they're not up in a beautiful tree overlooking a 20,000-acre watershed, they're locked in a basement with no windows and no clean air. And no cell phone Yeah, no cell phone and no people driving by saying `We love you.' People who are confined like that do it for years. If they can do it in those kind of conditions, I can certainly come up here and survive in this tree. I get nourishment from the fact that I am resisting the ecological collapse that is being wrought upon this community by a corporation that has taken over way more than just the Pacific Lumber Co. They also seem to have taken over the California Department of Forestry and the [North Coast Regional] Water Quality [Control] Board, and everyone else that is involved with approving the thousands of acres of clear-cuts. You make it sound like some vast conspiracy controlled by MAXXAM [Pacific Lumber's parent corporation]. I don't know if I would call it a conspiracy, but there's no question that it's corrupt. If the water quality board was really interested in protecting our water, they would not be cowed by pressure from Pacific Lumber. And if the Department of Forestry was really protecting the health and integrity of the forest, they would not approve every single THP that comes across their desk, especially when it involved steep and unstable slopes, or clear-cuts, which go hand-in-hand with herbicides and diesel fuels. At Thursday's Water Quality Control Board meeting, PL got a waiver on sediment discharge for THP 01-451, presumably clearing the way for more logging. What does that mean to the tree villages? I feel like we're on high alert now that Water Quality has crumbled at the feet of PL -- again. What does "high alert" mean? It means I'm sleeping very lightly, I'm up early in the morning, I'm very watchful for any hardhats coming towards the tree. A lot of people are sleeping next to their phones; we have a huge list of people who are ready and willing to respond if the tree-sits are threatened or if climbers are sent up. I have everything at hand in case they come so I can defend the tree. They're not going to catch me unawares. In the lower village they're talking about lock boxes to attach themselves to the tree-tops. Do you have something like that? With a tree that large it wouldn't seem like you could lock yourself to it. It's true, I am in a huge tree. I don't want to talk too specifically about what tactics I'm going to use, but they are going to have a very hard time getting me out. They will have to endanger my life to do it. Of course, when a climber comes up your tree, you know your life is immediately in danger, because there's nothing safe about evicting a person [from a tree] especially when tactics like pain compliance and zip-tied hands behind your back are being used. Are the trees in the upper village connected by traverses the same way as in the lower village? There are ropes connecting this tree to Wren's tree and a tree in between us. So you can go from tree to tree. People do that, but I haven't left this tree for nearly a year. That's my tactic. And so far your tree is still standing It's true, this tree hasn't been cut down. But they used about an entire can of orange and white spray paint on it. What did they paint? On my tree is says Remedy in bright orange letters. It also says Jerry, like three times, and the number 11 a bunch of times. They numbered all the treesits. They? Pacific Lumber; Carl Anderson, head of PL security was with them. Who knows what it means. I think it's a threat. It's intimidation. You know, they're powerless. They want to come and get me, but they can't because they don't have the skills. They don't know how to climb [Pacific Lumber uses hired climbers]. So instead they desecrate these ancient trees. This is like a 1,200-year-old tree, and now the base of it is covered in orange spray paint. It's not like they're marking the trees so they'll know which ones to cut, this is a clear cut -- they're going to cut every tree whether it's 2,000 years old or 2 years old -- so there's no reason to paint on the trees. They're just being vandals, basically. Granted they're vandalizing quote-unquote `their property,' but they're vandalizing one of the last ancient trees in this watershed. Do you think of the tree you're in as `their property'? On some level, sure. They have the paper work that says it's their property. Do you accept that they have private property rights, that they own the forest? That's a tough question. They own this property If you acknowledge that it is their private property, what gives you the right to stop them from doing what they want to do with it? Because it's not like you have one person's property over here and another person's over there, and it's all separate. What Pacific Lumber does on their property is seriously affecting neighboring properties; it's affecting the water quality for everyone. Pacific Lumber clear-cuts create mud slides and silt that fills our rivers. That's what gives me the right to be here. These trees are necessary to this area. They hold up the hills, they affect the weather, they provide habitat for endangered species. Less than 3 percent of the ancient trees are left, and cutting them is causing permanent damage to the environment and to the watershed. That's what gives me the right to be here. I don't feel like just because you own property you have the right to be completely irresponsible. At this point, there's really just one tree in history [Luna] that was saved by a treesitter. Do you accept the fact that you might just be delaying the inevitable? I think that's a possibility. I don't think there's anything a person can do to completely insure the safety of a tree. Look at Luna [which was partially girdled by a vandal after Hill's occupation ended]. I don't think there's a magic wand you can wave to make sure a tree is going to be saved. However, this tree is a lot safer with me in it. And for another thing, I'm not simply trying to save one tree. I'm trying to focus [attention] on a large issue. It's not just logging old growth, which I oppose, it's clear-cutting, an absolutely devastating practice that is still continuing. So you think you're saving more than one tree. Absolutely. I can save this one tree with my body, and I can try to do something about this whole issue with my actions. Everybody does what they can. I don't think we can count on any one hero to save these trees. It takes all of us. I'm just doing this. This is what I can do. IN THE NEWS | GARDEN | GOOD NEWS | CALENDAR

Comments? E-mail the Journal © Copyright 2003, North Coast Journal, Inc. |

in tree-climbing; it's a struggle from beginning

to end.

in tree-climbing; it's a struggle from beginning

to end.

ly

sent in Chain's direction by a logger). [below

photo of tree-sitter, Annapurna]

ly

sent in Chain's direction by a logger). [below

photo of tree-sitter, Annapurna] Last

week a tree-sitter, Michelle Renee Smith, was convicted of misdemeanor

trespassing for tree-sitting in the Mattole last year. She was

sentenced to three years probation and 100 hours of community

service with the stipulation that she stay more than 100 yards

from PL property. According to Assistant District Attorney Tim

Stoen, she would have faced 180 days in jail if she had refused

probation. She has also been ordered to pay an as-yet-undetermined

sum to compensate PL for sending Schatz up after her.

Last

week a tree-sitter, Michelle Renee Smith, was convicted of misdemeanor

trespassing for tree-sitting in the Mattole last year. She was

sentenced to three years probation and 100 hours of community

service with the stipulation that she stay more than 100 yards

from PL property. According to Assistant District Attorney Tim

Stoen, she would have faced 180 days in jail if she had refused

probation. She has also been ordered to pay an as-yet-undetermined

sum to compensate PL for sending Schatz up after her. r

a while.

r

a while. "I

came down after seven months," she said, slowly, sadly.

"Being in a tree-sit is wonderful, but it's kind of like

solitary."

"I

came down after seven months," she said, slowly, sadly.

"Being in a tree-sit is wonderful, but it's kind of like

solitary."

Tall

and dark with wild curly hair, LP is not universally liked by

his fellow tree-sitters. Some called him overbearing, a bit of

a macho man. Others have gone farther.

Tall

and dark with wild curly hair, LP is not universally liked by

his fellow tree-sitters. Some called him overbearing, a bit of

a macho man. Others have gone farther. tree-sitter,

and four-year veteran of the Marine Corps, had rappelled down

the tree to talk to her. Suddenly, a white pickup pulled up,

and a man got out, Thrasher. O'Brien walked over to stall him,

asking him to identify himself, to show her a badge number. Bear,

meanwhile, attempted to climb back up the rope. It was too late

-- Thrasher had already seen him.

tree-sitter,

and four-year veteran of the Marine Corps, had rappelled down

the tree to talk to her. Suddenly, a white pickup pulled up,

and a man got out, Thrasher. O'Brien walked over to stall him,

asking him to identify himself, to show her a badge number. Bear,

meanwhile, attempted to climb back up the rope. It was too late

-- Thrasher had already seen him. L

a sediment discharge waiver for THP 01-451 last week, the one

both the Upper and Lower villages ar

L

a sediment discharge waiver for THP 01-451 last week, the one

both the Upper and Lower villages ar e

located in, they've known it's just a matter of time.

e

located in, they've known it's just a matter of time.

Harvest Plan 01-451.

Harvest Plan 01-451.