|

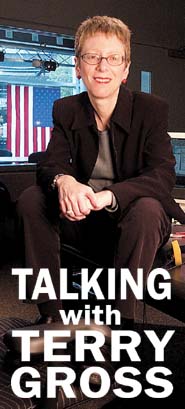

INTERVIEWby BOB DORAN YOU MIGHT NOT RECOGNIZE TERRY GROSS if you saw her walking down the street, but you probably know her voice. She is the host and executive producer for Fresh Air, one of National Public Radio's most popular shows. Broadcasting from the studios of WHYY-FM in Philadelphia, the show is heard by millions of listeners on almost 300 stations across the United States and on the World Radio Network. On the North Coast it airs at noon Monday through Friday on KHSU-FM 90.5. The core of each show is a series of extended interviews where Gross talks with writers, filmmakers, musicians or newsmakers. Last week's guests included the actor Kevin Spacey, bluesman Alvin Youngblood Hart, and Alexander Payne, the writer/director behind the recent film About Schmidt. Two journalists, Thomas Ricks and Vernon Loeb, who work the military beat for the Washington Post, discussed plans for war; another show with a writer and a lawyer focused on Illinois Gov. George Ryan's decision to commute the sentences of those on that state's Death Row. Next week Gross takes a break from the studio to hit the road. A speaking tour brings her to the West Coast and includes a visit to Arcata. On stage at HSU's Van Duzer, Tuesday, March 4, she will share excerpts from some of her shows and take questions from the audience. W hen we spoke, Gross was stuck at home on a snowy Sunday evening. A blizzard had hit Philadelphia the day before and she was "catching up" -- preparing her taxes and filling out an accident report regarding an errant bus that had sideswiped her car. We began with talk about the nuts and bolts of the show -- she works with segment producers who come up with ideas for guests and help with research --I mentioned some of the research I did in preparation for our interview, sorting through hundreds of sites on the Internet that mention her in generally glowing terms. "I am amazed at her insight and thorough understanding of the subjects she encounters. My choice for `best person to have over for dinner,'" writes one fan. Another adds, "I think part of what we're all amazed at is simply that she does her homework, something that most current underpaid, overworked rush-job journalists don't have the time to do." Gross, who has a knack for putting her subjects at ease, talked of growing up in Sheep's Head Bay, Brooklyn. She finished high school in 1968 and headed upstate to State University of New York at Buffalo. "Martin Meyerson, who had been [a chancellor] during the Berkeley Free Speech Movement, was the president at the time, and he had brought a lot of very liberal faculty with him. The campus kind of exploded around '68, '69. It was a pretty exciting time to start college. "It was a radical campus, both in terms of politics, the anti-war movement and the women's movement, but also the arts. There were all these new music ensembles that did works by Steve Reich who no one had heard of yet. There was a lot of avant-garde film and video." So how did an English major end up in radio? Gross said she was almost finished with college when she realized she had not really prepared for a profession. She "failed spectacularly" in a brief foray into teaching at "Buffalo's toughest inner-city junior high." "When I was growing up all the women I knew were either teachers, nurses or clerical workers, if they weren't full-time mothers." The key turned out to be a volunteer job at the campus radio station, WBFO, as one of the producers for a show called "Woman Power." "It was a feminist show produced by a small group of women. There were two goals: one was `consciousness raising,' the other was teaching women how to work in radio, because there were so few women on the air or making editorial decisions or in the control room. I totally stumbled into that and fell in love with it." She quickly learned how to record, edit and broadcast, and before long she was on the air. After the feminist show, she moved on to act as co-producer and co-host of an afternoon magazine show called "This Is Radio." The format was "anything goes," Gross said. "It could be a blues musician, political candidate. You could be talking about an issue, talking to a new author, or to a rock musician, a jazz musician, anybody who seemed interesting enough to talk to." It's no coincidence that it sounds a lot like the format for Fresh Air. WBFO's program director, David Karpoff, left the college station for WHYY in Philadelphia and created a similar show there called "Fresh Air." After about a year, in 1975, he hired Gross to work as host and producer. "The big difference is, when I started doing Fresh Air in Philadelphia, until the show went national [1985] the only people we had on were people who came to town. Now, ever since we've been national, we've had a budget to interconnect via satellite or fiber optic with all of the NPR bureaus and member stations. So a guest doesn't have to be in Philadelphia. We just call up whoever we want and send them to their closest NPR affiliate and talk to them from there." Even though it's rare for her to interview a guest in person, there's a sense of intimacy, a conversational tone that makes listeners feel like she is talking face to face. "My experience is that rapport has more to do with who the person is than with geography. I've had people sitting across the table and felt nothing click at all, whereas I can talk to someone thousands of miles away and think, `Wow, we're really on the same wavelength.'" Are there any advantages to doing remote interviews? "One is, if you're a bit of a coward, which I am, you can ask anybody anything without worrying about looking them in the eye. Also if you have a bad memory, which I do, you can look at your notes.... The distance accords a certain privacy and possibly even security." Is there something that helps bridge the gap? "I don't have a formula. It helps if you know something about the person you're talking to. They feel more relaxed and trusting. Also letting them know that they're free to tell me if something is too personal helps them relax. It means I'm not going to be the kind of interviewer who's struggling to get secrets out of them. Sometimes, especially for celebrities, I think an interview is like a war with a journalist in which it's your job to defend yourself against their attack." Some say journalists should have no friends. I ran across something the other day, a story in the LA Weekly about Martin Bashir's interview with Michael Jackson "I watched part of that. I was switching back and forth between that and Clinton on Larry King. It was stiff competition." There was a quote from The Journalist and the Murderer, a book by Janet Malcolm, where she says, "Every journalist ... is a kind of confidence man, preying on people's vanity, ignorance or loneliness, gaining their trust and betraying them without remorse." "I don't think that a journalist needs to do that to do a good job. The fact that someone is on the show is a good sign that we really respect their work. We turn down plenty of celebrities because we don't think that there will be much to talk about." I assume you are inundated with requests from celebrities who have a new book or movie coming out. "Of course. I realize some people are only going to talk to me because they have something they want to push. Fine. I'm happy to talk about the new film, if it's good, but I also want to talk about their body of work, their life. What bothers me in that equation is when someone comes on and they except to only promote their new thing, and if you ask anything else they're either going to be really obnoxious or walk out, or throw a little hissy fit. That's what bothers me, because we're not an infomercial." Have you moved toward giving more time on the show to the issue-oriented interviews as opposed to cultural programs? "When it was a local show, Fresh Air always had a little bit of everything, but when we became a national show we had to define ourselves more clearly. So we defined the show as an arts, culture, entertainment program. "A big turning point for us was the Gulf War in '91 -- Gulf War I. Once the war started, we thought, the only conversation we wanted to have was an ongoing conversation about the war. It seemed to be what everyone wanted to hear. That opened the door to talk about anything when the war had ended. "The mix of culture-to-issues depends on what's happening. For the last few weeks we've been doing a lot on terrorism and Iraq -- all the different points of view, journalists going in and out of the region, historians, experts. However, I really, really want to preserve a place on the show for the arts even if we do go to war. I don't want to see the arts community become a victim of the war; life is a hell of a lot more worth living with good music and literature in it." How do the arts become a victim of war? "They get shut out of all the media -- not all of it, but a lot of newspaper space and certainly broadcasting space is devoted to the war, and there are fewer slots for writers, for musicians. The big celebrities won't have a problem, but a lot of other people will. After Sept. 11 we had so few spaces that we gave over to the arts unless it was something like a concert that seemed relevant to the larger feelings of grief and fear. We were able to find arts things that spoke to the emotions everybody was feeling. But beyond that, I would really like to preserve room on the show for art and pop culture." There has been a lot of criticism of National Public Radio suggesting that content is slanted to the left. "That's right, but you know what? When we have someone on who has a pro-war point-of-view, which we have been doing, [we get complaints, too]. No matter what we do, we have people who love it, and we have people who are really angry." A number of websites have attacked you for "bashing the anti-war movement" in a program that aired Jan. 23. (The interviews included Mother Jones writer Todd Gitlin discussing the background of the International ANSWER, organizers of mass anti-war rallies, who pointed out that ANSWER's steering committee comes from the extreme left. He noted many speakers were off topic, diluting the central issue: opposition to unilateral war in Iraq. Another guest, Mara Verheyden Hilliard from ANSWER, was asked about ANSWER's association with the Communist group, the Workers World Party. Hilliard replied that the anti-war coalition is broad based and suggested that such questions bordered on "McCarthyite red-baiting." The websites generally do not mention a third guest, Bob Edgar, a former congressman, now head of the National Council of Churches. After dismissing questions about ANSWER's leftist agenda, Edgar made his own strong case against an attack on Iraq.) Again, there's a long history of criticism of NPR suggesting a leftist bias, but in this case, the perception was you're not left enough. "[That's what happens] if you're dealing with an issue that is very divisive. You have to understand, everyone on that show was against the war. It was kind of an intra-peace movement show. [We asked] was the demonstration held in Washington that day problematic because of the agendas at the podium? "The genesis of that show was from watching the peace rally on C-SPAN. I was surprised to see that the speeches seemed to be about supporting Mumia Abu-Jamal, who, by the way, used to work at 91-FM [WHYY] where I work, or about solidarity with the Palestinian people. Whether I agree with that or disagree wasn't the point. [The rally] seemed to have an agenda that went way beyond the peace movement. People who are against the war would not necessarily agree on all these extracurricular causes. Is that what people really want? "The most justifiable [complaint] would be from someone who is for the war. They would feel that their point of view wasn't represented at all, because it wasn't. It was a show about the peace movement." Is there influence from the outside directing the topics you address or the sort of guests you book? Your critics on the left suggest that NPR has moved to the right because of worries about funding from Congress. "First of all I think that is very untrue. I think NPR is a very responsible news agency and tries to give all sides, and I think they are successful at that. If in some people's minds that's right wing, let them interpret it how they please, but there's a difference between being fair and nonpartisan and being right wing. In terms of our own editorial decision-making, we're not even at NPR headquarters in Washington. We work very independently." You're coming out here as part of a series of lectures. What do you do out on the road as a performer? "I just ask questions (laughs). No, what I do is, I have a whole bunch of short sound bites. Usually in the sound bite something is going horribly wrong." So I suppose we'll hear things like the infamous Gene Simmons interview, Lou Reed walking out, Monica Lewinsky walking out, Nancy Reagan worrying that talk has strayed from her book.... "Exactly. And each of these humiliating, embarrassing, frustrating, aggravating moments has a story behind it. And I talk a little about how the show is put together and about myself. Most of the sound bites are pretty funny, too. What I like about them, I have this reputation as being the studious, sensitive interviewer. But of course sometimes things are just blowing up in my face. It's fun to show the other side! Then I also take questions from the audience. I get a taste of my own medicine." Interviewing the interviewer, which seemed to be a popular title for stories about you "That and `A Breath of Fresh Air.'" Is there any question you would never ask? "No, I don't think so. It depends who it is. Even the thing that's the most personal question in the world, there's going to be some writer or some performance artist who has done a show about that personal thing. There are inappropriate questions for individuals, but I'm not sure that there's any question that's inappropriate to absolutely anybody." IN THE NEWS | ON THE COVER | CALENDAR

Comments? E-mail the Journal © Copyright 2003, North Coast Journal, Inc. |