by GEOFF S. FEIN

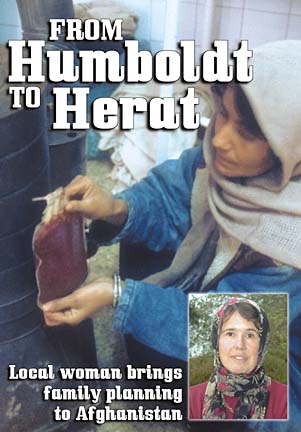

Above: A woman heats blood for a transfusion at Herat Hospital in Afghanistan.

Photo by Aghaghia Rahimzadeh.

Inset photo of Frederica Aalto by Geoff Fein

AFGHANISTAN. MERE MENTION OF THE NATION CONJURES UP IMAGES a guerilla war against the Soviet Union, years of tribal conflict, the rise and of the Taliban, fields of opium poppies, the ongoing war against terrorism.

AFGHANISTAN. MERE MENTION OF THE NATION CONJURES UP IMAGES a guerilla war against the Soviet Union, years of tribal conflict, the rise and of the Taliban, fields of opium poppies, the ongoing war against terrorism.

Less well-known is the fact that Afghanistan is one of the worst places in the world to have a baby. One in 16 pregnancies ends in the death of the mother, mostly from bleeding. It's the highest mortality rate for pregnant women in Asia and one of the highest in the world.

In November Frederica Aalto, international advocate for Six Rivers Planned Parenthood in Eureka, ventured to the shattered country with the goal of doing something about the situation.

Traveling with this determined 58-year-old was Dr. Malcolm Potts, a professor of maternal and child health at the University of California at Berkeley, and a veteran of international family planning efforts; Aghaghia Rahimzadeh, a 32-year-old Humboldt State University graduate student, who served as translator and photographer; and two Iranian doctors, Hamid Taravati and Farzaneh Bahar, both of whom have contacts within the Afghanistan medical community, such as it is.

Their mission: to introduce family planning and, more particularly, to assist Afghani women who have no access to pre- and post-natal care -- and who were denied medical attention altogether under the Taliban.

During a brief four days spent in Herat province in western Afghanistan, the group got a sense for what supplies and training are needed to help Afghan physicians better combat the leading killer of women in the country -- complications due to pregnancy.

Frederica Aalto, Dr. Malcolm Potts and Shaffiq Asdat, Afghanistan's Minister of Telecommunications.

Frederica Aalto, Dr. Malcolm Potts and Shaffiq Asdat, Afghanistan's Minister of Telecommunications.

They visited rural villages to assess the quality of medical care for women; they toured Herat's only hospital to learn how miscarriages are handled; and they met with government officials to find out what else can be done.

"I saw poverty and misery. Those things are sobering," Aalto recalled during an interview at her Trinidad home. "The depth of poverty is much worse in Afghanistan [than in America]."

Aalto, a resident of Humboldt County since 1974, has volunteered at Planned Parenthood for the past 13 years counseling local teenagers about sexuality and birth control.

Before she left, Aalto asked local pharmacies, doctors and dentists to donate supplies. What she got startled her.

"When I asked for supplies I thought I would [only] get enough to fill a suitcase," Aalto recalled. Instead, she got 56 boxes. "The outpouring was wonderful."

Why Afghanistan? "Women are dying there from things that could be solved easily. If you can do something to help, it becomes a question of how can you not do it."

Four years ago, Aalto visited Afghan refugee camps in Iran with the international aid organization Doctors Without Borders.

But this was her first trip inside Afghanistan itself.

Michelle of the main Eureka U.S. Post Office assists Ken Aalto, Frederica's husband, and Dr. Bill DAvis, a volunteer with Six Rivers Planned Parenthood, in shipping locally donated medical supplies to Iran.

Michelle of the main Eureka U.S. Post Office assists Ken Aalto, Frederica's husband, and Dr. Bill DAvis, a volunteer with Six Rivers Planned Parenthood, in shipping locally donated medical supplies to Iran.

A different world

Although it's often difficult to discern one nation from another at border crossings, Aalto was immediately able to tell Iran from Afghanistan.

On the Iranian side of the border the highway was paved. On the Afghanistan side it was a dirt road. There were no lights along the Dogharun-Herat highway, no road markers and nothing to keep a driver from veering off the highway. Every so often Aalto and her companions would pass a truck, rolled over on its side, resting in a ditch.

Stretching into the distance on either side of the road Aalto could see mounds of upturned earth, the telltale signs of land mine removal. Decades of wars have made Afghanistan one of the most heavily mined countries on earth. As the group would learn, the legacy of land mines is visible everywhere in the country in the form of people missing hands, feet, arms and legs.

Years of bombing have pockmarked the roads, so the 75-mile trip from the border to Herat City was a jarring experience; Aalto and her colleagues had to hold on for dear life as they were thrown about the inside of the van. Thanks to recent rains, it was also a muddy slog that took a full four hours.

Simply seeing where the road was was a challenge, according to Rahimzadeh. "In some places it didn't even look like a road," she said, explaining that the only way to navigate in such instances was to follow old tire marks left by previous vehicles.

Fortunately, their driver had experience along this route -- he drove a munitions truck during the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan in the late 1970s. On occasion he would curse the Toyota van they were riding in, wishing instead for a heavier vehicle, such as a tank.

Herat City was relatively untouched by the U.S.-led bombing campaign. It has not been plagued, like much of the rest of the county, by political instability. Ismali Khan, governor of Herat province, is loved by his people, according to Aalto, and has tried to change things for the better. He is selfless, Aalto said.

Frederica Aalto presenting an abolone shell from Humboldt County to His Excellency Ismali Khan, governor of Herat Province.

Frederica Aalto presenting an abolone shell from Humboldt County to His Excellency Ismali Khan, governor of Herat Province.

Nonetheless, the region has produced its share of refugees -- some 400,000 are thought to have fled to the neighboring countries of Iran and Turkmenistan.

Herat City is believed to have been founded by Alexander the Great in the fourth century B.C. With a population of almost 2 million, it's the largest city in western Afghanistan and lies between rugged mountains and expansive plains.

Few in the city were sad to see the Taliban leave, but it will take a while to get rid of certain customs, Aalto said.

"That will happen as life becomes easier," she said.

Women, for example, still wear burkas -- clothing that covers their bodies head-to-toe -- but they can now walk unescorted down the street. Although women have not yet been able to continue their educations, there are messages written on walls all around the city telling women to go to school.

Their first night in Herat City, the group stayed in a hotel. The other three nights were spent in a home. Arriving late one night, the group found that a meal had been prepared for them -- and that alcohol and opium were available as well. When they declined the opium, they were told it had all been paid for. That didn't change their minds.

"That was pretty wild," Aalto said.

The city had some paved avenues, but side streets were made of dirt. There was little electricity; vehicle headlights were the only means of lighting up roadways.

Nonetheless, Rahimzadeh was surprised to see how busy the city was. People were going about their day, she said, working, running businesses.

"I had expectations [Herat] would be destroyed."

A shortage of physicians

When the Taliban came to power they barred women from holding jobs. That left hospitals with no nursing staff and no female doctors.

In the post-Taliban era, women have rejoined the medical community. In Herat City, for example, 15 female physicians are now working at the provincial hospital, according to a September 2002 report by the Boston-based organization Physicians for Human Rights. However, as the report goes on to state, women doctors are concentrated in the city; in much of the rest of the province, trained female health care providers are scarce.

Male or female, doctors are in short supply. There are only 35 physicians in the entire province. Not only that, the provincial hospital in Herat City is the only hospital for 2 million people, Aalto said.

Potts said doctors in Herat City were doing the best they could in very difficult circumstances -- no medical books and limited supplies.

"[It] was very primitive," Aalto agreed.

The Herat Hospital Women's Ward.

The Herat Hospital Women's Ward.

The group, which visited one village, found abysmal living conditions in the countryside. People were living in earthen huts; they lacked electricity, heat and sewer systems. There were no trees, no grass, just barren land.

Some villagers shared their huts with their goats. They cooked with wood or animal dung, a practice that generates indoor air pollution.

Many villagers lacked shoes, which in winter means they must walk barefoot in the snow. Almost all were illiterate. When it's winter, people struggle to stay warm; when it's summer, they're fighting off cholera epidemics.

"People are miserable, it's beyond comprehension," Aalto said. "You see how easily they can die from day-to-day things."

According to the study by the Boston physicians' group, less than 1 percent of rural women giving birth are attended by a trained health care worker. About 97 percent are cared for by the Dauya -- untrained birth attendants.

Like most of the villagers, these attendants are illiterate. Their only training comes from observing pictures in books. In interviews conducted by the Boston doctors, the Dauya said they could save lives with better training and lamented the lack of supplies to deal with the most simple of birth complications, such as infection or bleeding.

Given all this, it shouldn't be surprising that 92 percent of all maternal deaths in Afghanistan occur in villages.

Rural women lucky enough to have access to a hospital still have obstacles to overcome. They must bring their own food and they must bring relatives to provide care, according to the report.

Avoidable deaths

What it all boils down to, for both rural and urban areas of Afghanistan, is an extraordinarily high maternal death rate, exceeded only by impoverished countries in Africa. In Afghanistan as a whole, there are 820 maternal deaths per 100,000 live births. The situation is somewhat better in Herat province -- 593 maternal deaths per 100,000 live births. But that's still appallingly high. In the United States, the rate is 12 deaths per 100,000 live births, according to the Physicians for Human Rights study.

"[In the U.S. an] obstetrician can practice a lifetime without seeing a death," commented Potts, the U.C. Berkeley family planning expert.

The largest cause of death among women is post-partum bleeding. One in 16 pregnant women will die because of such bleeding -- a result of spontaneous abortion or other complications, Aalto said.

"These [cases] are very simple to treat. In some cases bleeding can be stopped just by taking a pill."

The study also found that women and their families don't know the warning signs of potentially lethal conditions during pregnancy and childbirth and cannot therefore avert potential complications. No wonder. Only 11 percent of pregnant women receive prenatal care, according to the Boston study.

Aalto and her companions witnessed other problems besides a lack of family planning. They saw a number of people with birth defects ranging from children unable to speak or hear to people missing limbs. Neither Aalto nor Potts had an explanation.

"I was astonished," Potts said.

Potts said he'll try to bring an orthopedic doctor on his next trip to help those with missing limbs due to birth defects.

"We hope to add on any sort of medical care we can [bring], besides family planning," Aalto said. "They need every kind of help imaginable."

Aalto believes the efforts of Potts and herself will have a positive impact in the city and in villages.

"[Our] hope [is that] it will establish well in Herat and spread out to the rest of Afghanistan from there," she said.

No access to male physicians

Western nations have promised aid to Afghanistan, but people told Aalto the aid was not making its way out to Herat. Most of it was going straight to Kabul, the capital, and staying there.

Even though Herat Province may not yet be reaping the benefits of international aid, the area does have some well-stocked pharmacies, Aalto said.

"There were an amazing number of pharmacies, one on every block and many filled with modern medications," she said. "They had birth control pills [from] Germany, [smuggled] in through Pakistan."

A month's supply of pills costs 10 cents. Pharmacies also had injectable birth control that works for three months. Each injection costs 50 cents. But many Afghan women don't know about this or they live out in rural areas where birth control is unavailable, Aalto added.

Aalto and her colleagues also saw women being treated for miscarriages. Potts, however, had to stand behind a screen during the exams. In Afghanistan, male doctors do not yet treat female patients.

One of the patients the group saw had a miscarriage almost five months into her pregnancy. The woman had been bleeding continuously for 12 days. "It was amazing she was alive," Aalto said.

Doctors at the hospital had to perform an abortion on the woman to remove remaining fetal tissue.

The second case was an early-term abortion. But rather than using the vacuum syringe method favored in the West, the doctor in Herat was performing a more dangerous procedure: dilating the cervix and scraping the uterus. The risky practice can cause perforation of the uterus, Aalto said.

Potts was upset by the procedure. He offered to help, but the patient did not want a man treating her, Aalto said.

"[The procedure is] very painful," Potts said. "[Doctors in Herat] had been taught to use the new method." But the syringes, which cost about $5 and are reuseable, were not available to the doctors, Potts said.

"[Doctors] become ingenious at using the limited resources [they have]," Potts said.

Women undergoing the procedure did not receive any anesthetic, a normal practice in the West. Potts was amazed at the woman's ability to endure pain.

Open to birth control

Aalto also met with a group of women, most of whom were using contraception. Only one woman in the group said it was a sin (she was scoffed at by the others), Aalto said.

She also recalls talking to one married man who had seven kids. He said his wife was opposed to contraception.

"We encouraged him to learn about having a vasectomy," Aalto said.

According to Aalto, Afghanistan has no issues with teen pregnancies or single mothers, and AIDS is nowhere near the problem it is elsewhere. The Afghan people are more concerned with the basics, such as food and sanitation.

"Their needs are great," she added. "They need clean water, electricity and roads."

The people also need the land cleared of mines. Until that is done, people can't farm, Aalto explained.

But even under such adverse conditions, the people in Herat are trying to move forward.

"They may be down but they are not out," Aalto said. "Despite lacking [so much], they keep going."

Even government officials are pitching in. The minister of telecommunications, for example, does not take a salary; and the governor of Herat Province lives not in a palace but in a home rented from an elderly woman, Aalto said.

A female doctor whose husband was abused and killed by the Taliban said she is dedicating her life to helping the poor, Aalto said.

"There are a lot of people like this; they are doing what they can," Aalto said.

LEFT: A vasectomy clinic in Iran. RIGHT: An Afghanistan logging truck.

Photos by Frederica Aalto

The next step

Aalto and Potts are hoping to return to Afghanistan later this year. They want to bring urgently needed medical supplies and training to Afghani doctors in the areas of obstetrics and family planning. Once Aalto and Potts have a plan, they will begin pursuing funding.

From her Trinidad home, overlooking the rugged California coastline, Aalto said she was disappointed she could spend only four days in Afghanistan. Even so, she was aware of the valuable connections the group made. Already she and Potts are trying to get a hold of an Iranian soap opera with a family planning theme. Aalto said the program is very popular in Iran. The plan is to buy the shows and air them on Afghanistan state-run TV.

Aalto would eventually like to expand the program beyond family planning, but for now it will focus on women's needs.

"Our time was well-used. Every contact was positive," she said. "This trip was very inspiring. It gave us the confidence that we can do this."

Editor Keith Easthouse contributed to this report.

Frederica Aalto is giving a talk on her trip at 7 p.m., Tuesday, Feb. 18, at St. Alban's Episcopal Church, 1675 Chester Ave., Arcata.

Friendly and 'progressive' Iran

IN CONTRAST TO AFGHANISTAN -- and, for that matter, the United States -- family planning in Iran is given high priority. The government airs TV shows with family planning themes and distributes posters and literature on the subject. It also educates its rural citizenry about the importance of things like birth control.

Frederica Aalto, a family planning volunteer with Six Rivers Planned Parenthood in Eureka, learned of Iran's "extremely progressive" family planning effort after attending a United Nations conference on family planning in Cairo, Egypt, in 1994.

"I was amazed," she said. She had thought the Muslim world would be uniformly opposed to family planning.

It was at that conference that she met two Iranian physicians, Dr. Hamid Taravati and Dr. Farzaneh Bahar, who helped set up her recent trip to Afghanistan.

For many Americans, Iran will always be remembered for the taking of the American embassy and 56 hostages in 1979. It has been labeled part of an "axis of evil" by President Bush. Currently, the country is undergoing changes as younger Iranians are seeking more freedoms while the ruling religious leaders are attempting to squelch those desires.

Aalto said Americans are mistaken if they think Iranians are rabidly anti-American. "What people hear about Iran is inaccurate. People there are friendly," she said.

Aalto told a story, relayed to her by Iranians, of how drivers refuse to pick up hitchhiking Mullahs -- Iran's religious scholars. In one instance a driver picked up a Mullah resting beneath a tree. The driver asked the Mullah why he was sitting there. The Mullah explained that he had had trouble getting a ride so had decided to rest in the shade.

A few miles down the road the driver pulled over along a desolate stretch of highway and ordered the Mullah to get out. The driver told the Mullah he didn't deserve to rest in the shade for what the Mullahs had done to Iran.

Aghaghia Rahimzadeh, a Humboldt State University graduate student, accompanied Aalto on her journey this past November. An Iranian, she said many families in Iran have satellite television that gives them access to American programming.

"They are up [to date] with current fashions, music and trends," Rahimzadeh said. "Seventy percent of the population is under 25. They all want Hollywood and McDonald's."

Aalto found that Iranian feelings about a U.S. war with Iraq varied, but many Iranians were not opposed to the idea.

"[Iranians] still harbor anger at Saddam Hussein for the Iran-Iraq war and because of [Hussein's] treatment of the Kurds," Aalto said.

The Iran-Iraq war lasted from 1980 to 1988.

Rahimzadeh said people she spoke with hope the United States will force a regime change in Iran as well.

"People are so fed up with the [political] system. Inflation is high, unemployment is high, people are struggling to get by," she said.

-- reported by Geoff S. Fein

Comments? E-mail the Journal: [email protected]

© Copyright 2003, North Coast Journal, Inc.