|

COVER

STORY | IN THE NEWS | ARTBEAT | THE HUM | CALENDAR

by BOB DORAN

THE EASY EXPLANATION IS THAT

Bruce Cockburn is a singer-songwriter from Canada, but that's

a serious oversimplification. He is also a poet-reporter, a activist-humanitarian

and a damn good guitar player.

Cockburn is on the road right

now; when I caught up with him he was in Princeton, N.J., about

to play another concert. It's another stop on a musical journey

that began in the '60s, one that has taken him to the far corners

of the world, sometimes to play music, sometimes just to see

what's going on.

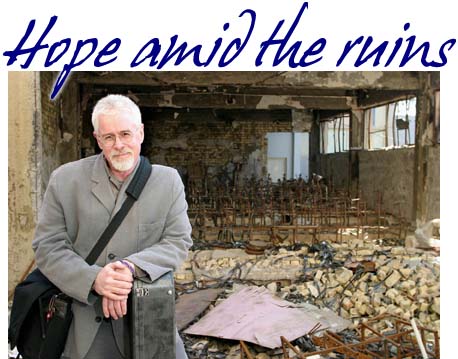

[Bruce Cockburn

in front of a bombed campus theatre in Baghdad. Photo: Linda

Panetta/Optical Realities Photography. www. opticalrealities.org]

When he traveled to Baghdad

in January, he went with a group that included an activist bishop,

a nurse and a photographer -- he had a guitar with him, but his

mission was to observe, in part so that he can bear witness in

song. He says he's still processing what he saw there.

"I got back just in time

to leave for this leg of the tour, so there wasn't any time to

sit around and process Iraq, but it's taking shape in my mind

as we go and I look over my notes. Linda Panetta, the photojournalist

who went with us, was showing me some photos of the trip, that

brought things back."

NCJ: What were things like

in Baghdad?

"What I found in Baghdad

was a place that showed all the traces of having been a fully

developed, thriving First World city, one that, after 13 years

of sanctions and a war, was looking pretty battered. A lot of

the city is still standing because of what they call "smart

bombs" -- I'm not comfortable with the term, they're not

very smart and the people who use them aren't, either -- but

they were selective about what they bombed, so there's a lot

that wasn't conspicuously damaged by the war itself. But if you

look a little closer you see obvious signs of fighting in the

streets, bullet holes in the walls, stuff like that."

NCJ: So-called collateral

damage?

"Government buildings were

deliberate targets. The collateral damage was the result of Saddam's

policy of putting military and otherwise sensitive institutions

next to hospitals and schools. For example, you have a military

institution that was bombed that happened to be next to the art

college in Baghdad, so the college lost its cinema school --

their theater was destroyed. There are still shards of movie

film flying around on the ground."

NCJ: What did the people

tell you? How do they feel about what's going on there?

"The people, everyone almost

without exception, said to us that they were glad that Saddam

was gone. And generally people were grateful to the U.S. for

that, but the goodwill that that might have brought towards the

U.S. is draining away really fast -- it's virtually gone because

people are confronted with such difficulties in their daily lives,

and they blame the U.S.'s policies for that.

"For instance, in the city

of Baghdad, electrical power is a part-time thing. You've got

electricity in the daytime and it goes off at night, because

there's not enough to go around. People who can afford them have

generators, but people made comparisons to the aftermath of the

first Gulf War when Saddam had the power up and running in a

week. Here it is almost a year later and the Americans can't

get it together.

"This is what the Iraqis

are seeing from their point of view, and it's just one small

example of how they see the priority of the occupying forces

being about anything other than the welfare of the Iraqi people.

The people sometimes used strong language to express their feelings

about the American occupation, but there wasn't a lot of animosity;

there was frustration and resentment, but not outright hatred."

NCJ: You brought your guitar

along. Did you play with Iraqi musicians?

"On one occasion I got

to play with an oud player; the oud is the Arabic lute, it's

a beautiful, beautiful instrument. There was this young guy in

his 20s who was a very accomplished lute player and a good singer.

We had been invited to the same lunch at a gallery operated by

a visual artist; while he was cooking lunch the oud player played

and sang. After lunch I pulled out my guitar and the guy immediately

grabbed his oud and we started jamming, just improvised for a

while. It was amazing actually, we really connected. I got to

play in other circumstances, too, just because I had the guitar

along. We went to a shelter for disabled women, for example,

and I pulled the guitar out there and played. It gave people

a chance to think about something other than their plight --

there was a lot of joy that came out of it."

NCJ: Of course, the role

you play as a musician is much more than offering a soothing

moment. You do a lot more. You show the darkness in the world,

but also offer hope for the future.

"For me, hope is a recognition

of the reality of things. I don't really think much about hope

or its absence. I use the word because it's convenient, because

others understand the idea. Without trying to get too cosmic,

it's really because everything in the universe is connected to

everything else -- and that includes us. We're connected to everything;

we're mutually interdependent -- and if we recognize that, somehow

the concept of hope and worrying about the future just pales

and falls into the background, because reality is big and vital

and ongoing, no matter what happens.

"You can express it in

terms of the divine or in terms of physics or whatever, but everything

overlaps and ends up being what I refer to as one big soup --

or Big One Soup. Everything is part of everything else, so the

evil [in the world] is part of the good and the good is part

of the evil, and they're all different facets of the same gem

that is life.

"That doesn't make the

evil less deplorable or the good less enjoyable, but it makes

it possible to keep going -- on the assumption that everything

else is going to keep going too, which is kind of like hope.

In order to move forward with your life you have to think it's

about something, that it's worth doing, otherwise, why bother?

Why not just sit there and die?

"People who face extreme

difficulties develop an attitude that says, `If I do things right

and don't screw up too much and I'm lucky, I'll make it through

this day OK.' I think there are people in Baghdad who feel pretty

helpless, who realize that they may never get out of their circumstance

and their kids might not, either. Even those people are willing

to look for bright spots and take advantage of whatever possibilities

come up."

NCJ: Did you get a sense

talking to people in Baghdad that they look forward to a time

in the near future when things will get better?

"No, I didn't. I think

people are really worried about how things are going to be. They'd

like to envision a time when things improve, but it's hard. The

next year or so is going to be crucial and if the right things

don't fall into place, who knows what the future will bring?"

NCJ: A lot of people are

thinking the same thing -- about the election coming up here.

"That's right. You have

to hope. And no matter how helpless you feel, get the hell out

there and vote, because if you don't, then the result will be

guaranteed."

Redwood Community Radio

KMUD-FM presents Bruce Cockburn in concert, Sunday, Feb. 22,

at Mateel Community Center, Redway. Music begins at 8 p.m., preceded

by a Mexican dinner benefiting the station starting at 6 p.m.

Tickets are $20 in advance. For details, call KMUD at 923-2513.

Bob

Doran

COVER

STORY | IN THE NEWS | ARTBEAT | THE HUM | CALENDAR

Comments?

© Copyright 2003, North Coast Journal,

Inc.

|