|

IN

THE NEWS | GARDEN | GOOD NEWS | CALENDAR

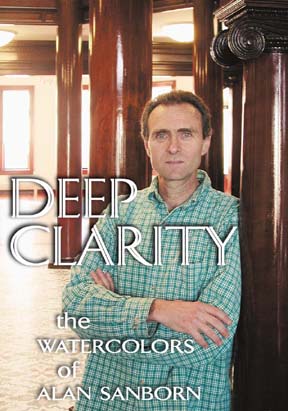

by BOB DORAN

THERE'S SOMETHING THAT DRAWS

YOU INTO ALAN SANBORN'S paintings, a depth of vision that goes

beyond the almost photographic attention to detail and the keen

sense of light and shadow.

A

Sanborn retrospective opened last week in the largest gallery

at the Morris Graves Museum, with 26 of his watercolors on display.

His landscapes often show the beauty found in unexpected places:

a backyard garden, an empty lot, the remnants of an old pier

on the waterfront. A

Sanborn retrospective opened last week in the largest gallery

at the Morris Graves Museum, with 26 of his watercolors on display.

His landscapes often show the beauty found in unexpected places:

a backyard garden, an empty lot, the remnants of an old pier

on the waterfront.

Even if you do not frequent

art galleries, chances are you've seen Sanborn's work. His paintings

of gardens adorn the brochures and posters for the North Coast

Growers Association Farmers' Markets. He has contributed several

pieces to the public radio station, KHSU, to be reproduced as

posters for pledge drives.

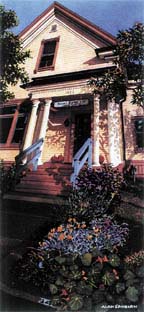

And if you are a patient of

Dr. Richard Benoit, an Arcata dentist, you get a postcard version

of one of Sanborn's paintings every time you have an appointment:

The reminder card bears a reproduction of a painting Sanborn

exchanged for some dental work (the painting is an exterior view

of Benoit's office, a historical home, shown at left).

MAINE ROOTS

Asked in an interview with the

Journal last week why he chose watercolor as his medium,

Sanborn, an upbeat 52-year-old, said he couldn't say for sure,

but he suspects the seed was planted early.

"I was brought up in Maine,

a place with a long history of watercolorists," he said

as he settled into a cozy breakfast nook in the corner of the

kitchen. It's the only room in his Arcata home that doesn't have

one of his paintings on the wall; instead, the cabinets are decorated

with artwork by his sons, Liam, age 9, and Aidan, age 7. Sipping

periodically from a steaming cup of tea, he began talking about

Maine's art history and his own path to art.

"John Marin, the premier

watercolorist of the United States in the first half of the 20th

century, did abstract landscape watercolors and he did many of

his paintings in Maine. Also, Winslow Homer settled in Maine;

Edward Hopper painted a lot in Maine; Andrew Wyeth lived half

his life in Maine. Those things were all around me when I was

growing up."

While he was in high school, the family moved to

Los Angeles. When he graduated in 1968, he chose Humboldt State

because it was "as far away from Los Angeles as I could

get and still stay in the state school system." While he was in high school, the family moved to

Los Angeles. When he graduated in 1968, he chose Humboldt State

because it was "as far away from Los Angeles as I could

get and still stay in the state school system."

He loved nature and the outdoors

and thought he might become a forest ranger, so he enrolled as

a forestry major. "It took me about a year to know that

forestry didn't have much to do with being a forest ranger,"

he said. "I changed to oceanography. That lasted

about a year, then I realized that I'd been taking science classes

my whole life and I was tired of it. I switched to journalism

and graduated in 1973."

FINDING HIMSELF

Even though he had a natural

talent with a pencil -- he could always draw just about anything

-- he had not studied art, not yet. That shift in focus would

come later. Journalism degree in hand, he took a break from education

to travel, rode across Canada on a bicycle, returned to Maine

for a while, spent a year in Europe and another in Yosemite,

and eventually ended up back in Humboldt.

While he would not get into

painting until after re-entering Humboldt State, signs pointing

him in that direction popped up during his journey. He recalled

a moment from his Canadian bicycle trip. "I stopped in a

little museum in Banff. I was looking at paintings and saw this

watercolor. It was sort of precise, a landscape with buildings.

I saw the way the colors overlapped, the edges that didn't quite

match up. It was beautiful.

"I think that was the first

time I had really looked at how a painting is put together. I

realized, `Oh, it's a watercolor, that's why these things can

happen.' It's not that I decided right then to paint, but it

stayed with me."

The notion that he might pursue

painting didn't really hit him until he went to Europe. In particular,

he was impressed by the dramatic Spanish artist Francisco de

Goya.

"When I saw Goya's paintings,

I realized that there was something more to art than just representation.

I knew I had to paint. When I came back here I was thinking I

either wanted to be a writer or an artist."

He enrolled at Humboldt State

to work on an advanced degree in English, but quickly switched

to art. With urging from the painter Glenn Berry he enrolled

in the school's masters program. About a year into his studies

he took a class from watercolor master Bob Benson.

"I think Bob is one of

the best watercolor painters in the country," Sanborn declared

with a touch of reverence. "I don't know of anyone who uses

the medium to its full extent the way he does, and he has a strong

vision of landscapes. He's the only landscape painter I know

who can paint a 360-degree landscape, all in one little rectangle.

From working with Bob I realized that it's an endless medium.

"I have to admit, I tried

to paint like Bob Benson. Even well after I was selling in galleries

and doing realism I still wanted to do Bob Benson paintings.

That was my aim, to paint like him. Now I paint like me."

Benson, who's taught art for

28 years, said Sanborn was the only student he ever had "who

was exhibiting his paintings in a gallery in Los Angeles before

the semester was over." Noting that Sanborn already had

well-developed drawing skills, Benson said, "I was

just in the right place at the right time to be a catalyst.

"I really admire his love

of the medium and how he's pushed it in his own individual direction,"

Benson added.

A RELUCTANT RETROSPECTIVE

At this point Sanborn has been

painting professionally for almost 20 years. Having produced

a steady stream of successful work, he has established relationships

with several galleries across the country.

Early on, he sold his work locally

through Atlee and Atlee, a gallery in Eureka that closed in the

early 1990s. Since then, he has not hooked up with another local

gallery, in part because he sells a considerable amount of work

directly to customers in studio sales at his home.

So the Graves retrospective

is one of the few times he has mounted a major exhibition in

this area. He admitted that he doesn't particularly like "doing

shows." When he was urged by friends like the painter Floyd

Bettiga to submit a proposal to the Graves, he resisted.

"Doing a show basically

means painting hardcore for about nine months toward a particular

goal -- and holding onto everything. You can't give anything

to galleries or sell anything out of your house. Then the show

will usually be a mixed bag because in nine months you might

only do two or three really good paintings, then the rest of

the show has to be whatever else you produced.

"Not long after I talked

to Floyd I saw someone else's show, a retrospective. I thought,

`Hey, I can do that.' I realized that some of my best paintings

are on walls here in Humboldt County, things I could get together

without much trouble. I gathered slides of all the things I knew

I could get my hands on here and narrowed it to 50 paintings."

By the time the show was hung

that number was cut almost in half. The 26 paintings on display

are what he sees as the best of his work. Through them it becomes

apparent where he finds beauty: a pile of junk against a wall

is as striking as the flowers standing nearby.

BAD PHOTOS BAD PHOTOS

Sanborn knows he can paint whatever

he wants. So it comes down to what window on the world he wants

to recreate with his brushes.

When asked how he chooses, his

initial response was vague: "When I see something I want

to paint, that's what I want to paint -- period."

Pressed for details, he repeated

himself and then elaborated: "All I can say is I see something

I want to paint: a place, a time, a light, the way light falls

on things or the lack of light. I'll take a lot of photographs,

sometimes they're so bad I can't find what it was I saw."

It's not hard to jump to false

conclusions about Sanborn's work. When you see the fine detail

in his paintings and the way the shadows and light interplay,

you think, `This looks like a photograph.' And you might guess

that his skill is an ability to take a great photo and reproduce

it using watercolors.

A partially done painting on

his worktable shows the error in that assumption. Several photographs

are scattered across the top of the piece, simple snapshots used

as reference to show him the shape of a squash leaf or what a

jumble of poppies looks like. They are not great photos, not

even good photos.

"I could probably be a

good photographer, but I'm not," he conceded. "That

would take too much time and I don't own great cameras. I'd say

about two-thirds of the time I work from really bad photos. I've

taken pictures at noon, which is good for showing details. I

just change the light and create shadows to make it afternoon."

Benson agreed that Sanborn's

photographs are "terrible," but said that's where the

art comes in. "It forces him to come up with the content

of the image on his own. People might think his work is not that

creative because it's so realistic. But there are a lot of creative

choices in how he develops the light, the edge quality of forms,

the spaces, the shadows, the areas that are background or subordinate.

That's where you'll find a lot of Alan's inventions.

"If you look at the big

sweep of the image, it is very impressive," Benson went

on. "But I like to get up close and look at the textures

of the in-between areas."

INTRIGUING INTERSECTION

When Sanborn selected the paintings

for the retrospective, he realized that there was a through line

in his work, something he called "the human landscape."

The subject matter in the pieces

varies from rusting trucks to beautiful gardens, from pastoral

landscapes to city streets. While he often paints a world where

humanity's presence is apparent, only a few of the paintings

in the exhibition show people, and only a couple show an untouched

landscape. What is depicted is the intersection of civilization

and nature.

"I rarely paint nature

in a pure form; it's always been how man interacts with the landscape,"

he explained. "When I started I was socially or maybe philosophically

involved with my painting. I was trying hard to show the human

landscape -- the one we live in with all its signs and wires,

markers, different shaped buildings -- somehow contrasting that

with the natural landscape it's set in. [I wanted to] make some

statement about the human mind and the human existence, about

how muddled and cluttered our minds are -- and our lives.

"I was painting the chaos

of man in general, then I was finding that I was more

drawn to things behind the scenes: things like trash cans behind

houses. Then I was drawn more to things that showed the passage

of time: waste and decay, the changing seasons.

BACK TO THE LANDSCAPE

"I feel like a lot of the

paintings in this show honor what you might call the Humboldt

school of landscape, the school of painting that has the land

as its derivative," he went on. "There's a tradition

of landscape painting, particularly with artists like [George]

Van Hook and [Jim] McVicker. And [there are] a lot of people

who moved here for the land and haven't been academically involved,

Sunday painters as they call them."

Since he settled here Sanborn

has seen phenomenal change in the county's art scene. While Hobart

Brown and his friends were turning Ferndale into an artist's

colony, the art department at Humboldt State was burgeoning and

a community was developing in Old Town with painters tucked away

in studios above the commercial district. Organizations like

the Humboldt Arts Council and the Ink People became a vital force.

Amid that change came a new respect for landscape painting.

"There are so many people

involved in landscape painting here, people who moved here because

they love the land: They love the forest, the ocean. People who

were fleeing the cities in the back-to-the-land movement, and

since then more have come because they are drawn to the area's

physical beauty."

As Humboldt's economy shifts

from resource extraction to tourism, artists serve a new function.

For some a picturesque vista rendered in oils or watercolors

can become a political statement.

"Beyond recognizing the

beauty of the landscape, [landscape painters] recognize the social

and political aspects of land in this time," Sanborn contended.

"I feel like there's a political reality based around land

use up here, and when you paint the land, there is a social/political

value to it. Most landscape painters up here are aware of the

often stormy political aspects of land use.

"But then again, you can

only get so philosophical about your paintings. If you're doing

realism or representational stuff, there are times when you want

to paint something simply because of the way light shines on

it. You think, `This is what it's all about, painting what you

like when you see the light.'"

Editor Keith Easthouse contributed

to this report.

In the artist's words

Stephen's Pick-up -- 1987 Stephen's Pick-up -- 1987

"It's a dynamic

composition, but I did not set anything up. I left the pitchfork

right where it was. The truck belongs to some friends, the McCollums.

They own about eight acres on the Smith River where they have

a big garden.

"Stephen used

to go up in the woods to find downed trees, and he would cut

his own lumber for a lot of things. That's the load on the back.

His father was a field foreman for Pacific Lumber back when it

was a family owned business."

"To me the truck

symbolizes a time and an era of rural farming: the last generation,

a time when farm work was generally done by hand, but with a

couple of big machines, the pick-up truck and the tractor. Before

corporate farming took over there was a generation of family

farmers who worked the land with horses, then for a generation

and a half, a small pick-up and a tractor were the mainstays."

Humboldt Bay --

1989 Humboldt Bay --

1989

"This one shows

the bay right near the Eureka Marsh. The painting is owned by

Carol and Charles Ollivier. He was the president of the Longshoreman's

Union and on the Harbor Commission at the time. His wife Carol

grew up in Eureka and they used to take the ferry across the

bay near here.

"I painted it

just because I used to run and walk and wander around Eureka

when I lived there in the '80s. I took the picture because I

just loved the way it looked with the remnants of some old structure

and the old wharf that's no longer used."

(Note

the overexposed section along the horizon -- that's purely a

photo effect). (Note

the overexposed section along the horizon -- that's purely a

photo effect).

"Sometimes I

leave things the way they are in the photo. That's how they figured

out that Vermeer was a photo-realist who used optics in his paintings;

he would leave little effects like that in his paintings."

(This painting was

reproduced as a poster for a KHSU fund drive.)

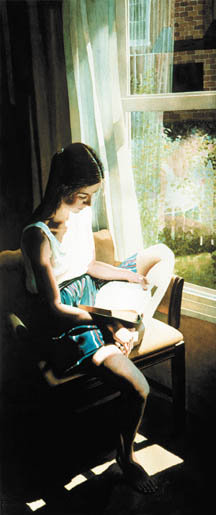

Lisa Reading -- 1991

"This was a birthday

present for my wife, Lisa. I get her to pose every once in a

while. It's easier if she's reading or doing something where

she's still. I think it's successful technically and it has a

good feeling. It definitely feels like Lisa; she tends to be

quiet and she seeks out the warmth. I also like the way things

are just suggested in the shadows. I love to take people and

have them start to get lost in the background."

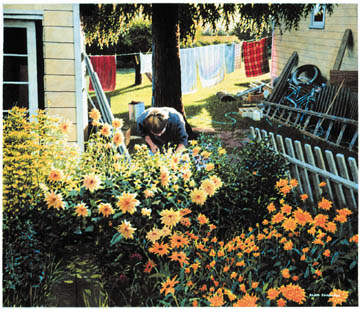

Chris in Her Herb

Garden -- 1994

"My favorite

painting. I had it in a gallery once but instantly realized I

did not want to sell it. I love it because it captures what I

started to do philosophically. It shows the clutter of what it

is to be human and at the same time puts it in a context that

has a lot to do with the way we live here, where human life and

nature are sustainable and live together in harmony and in chaos.

"You

see today's work being done [the clothesline]; there's all the

work that's not going to be done [the jumble of things against

the wall]. There are things waiting to be done like the molding

leaning against the building. She's in an herb garden that has

been taken over by flowers, gathering herbs to make dinner. "You

see today's work being done [the clothesline]; there's all the

work that's not going to be done [the jumble of things against

the wall]. There are things waiting to be done like the molding

leaning against the building. She's in an herb garden that has

been taken over by flowers, gathering herbs to make dinner.

"The composition

is completely chaotic, but with a strong center: a redwood right

in the middle. The redwood is a symbol of what we are. The light

bounces everywhere, but it seems to have a calmness despite the

chaos. It represents life: If you don't worry about everything

being finished you get to enjoy it.

Tractor,

Farm, Mountain -- 2001 Tractor,

Farm, Mountain -- 2001

"This is the

upper Appalachians. It's not from my own photograph. It was a

National Geographic photo, a huge picture of people auctioning

off farm equipment, that's what the photo was about. At the top

in a thin strip it had this vista of the mountains, but not exactly.

I added things, changed things. The trees weren't there, the

tractor wasn't there, the house was different.

"Both of my grandfathers

had farms, one just had horses, one had a tractor. One of those

farms was in a place like this where the White Mountains come

into Maine. So this comes from my past, but it's also a comment

on the abandonment of the family farm. The seasons are changing,

it's rich and warm and vacant at the same time."

Presumpscot

River -- 2003 Presumpscot

River -- 2003

"This is where

the Presumpscot River meets the ocean, right at the edge of Portland,

Maine. It's where my father swam when he was a kid. It's where

my brother and I dumped his ashes when he died.

"I've done about

10 paintings from that spot so far. It was a particularly special

day; there was a horrible thunderstorm that stopped right when

we got there, when we went to spread his ashes. To me it's just

typically Maine, a calm mundane moment at a mundane place.

"If I paint for

anybody, probably I paint for [my father]. He was a strong influence,

even though he wasn't much like me. He was an NRA member, a lifelong

Republican, Marine Corps alumni, a Mason. I couldn't be more

different socially and politically. Nevertheless, I think our

aesthetic was very similar. When I have a painting I'm particularly

proud of, I [think] `Yep, he's going to like this one too.'"

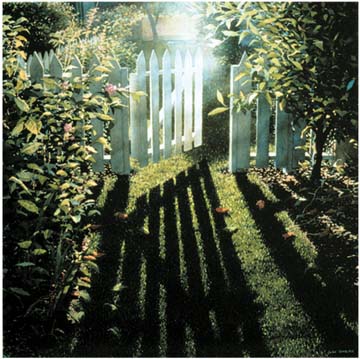

My

Father's Gate -- 2000 (near top of article)

"Another one

about my father. This is my father's gate. He owned the house

I live in. He bought it and they were going to move up here to

retire, but he kept putting off retiring, so after a few years

we bought the house. When he still owned it, he built this gate.

Years after he built it, it still opened and closed perfectly.

"I saw the way

the light was shining on it one day, the way the pickets throw

shadows to form a pyramid with the opening into the yard at the

apex. Our yard never looked so good. I ran and got my camera.

"When I painted

it, it was just another painting, but now I know it's a very

spiritual painting, it shows something deeper. My father and

my mom opened a gate for me to go through. The pyramid shows

all of the generations that got me to where I am. I think about

my own kids, wondering if I will be able to honor the pyramid

of those who came before me by making a gate as easy to pass

through, as brilliant as this for my children to go through."

THE HUMBOLDT ARTS COUNCIL

presents a retrospective exhibition of watercolor paintings by

Alan Sanborn in the William Thonson Gallery, Jan. 16 through

Feb. 23, 2003, at the Morris Graves Museum of Art, 636 F St.,

Eureka. An opening reception will be held from 6 to 9 p.m. on

Feb. 1, during Arts Alive!

IN

THE NEWS | GARDEN | GOOD NEWS | CALENDAR

Comments? E-mail the Journal: ncjour@northcoast.com

© Copyright 2003, North Coast Journal,

Inc.

|