|

IN

THE NEWS | CALENDAR

by GEOFF S. FEIN

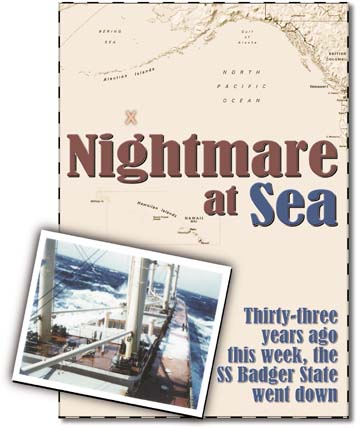

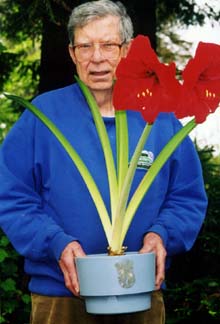

IT DOES NOT APPEAR THAT ANYONE REALLY KNEW William

Burnette. [ photo at right,

2002] Those who were acquainted

with him said he was a loner, never married. IT DOES NOT APPEAR THAT ANYONE REALLY KNEW William

Burnette. [ photo at right,

2002] Those who were acquainted

with him said he was a loner, never married.

Burnette lived in his Cutten

home, with his mother, for more than 20 years. She died in 1989.

His father married three times. Burnette, however, didn't keep

in touch with most of his relatives.

He did stay in phone contact

with Peggy Winstead, a step-niece in Florida. Even though he'd

call a few times a month, Burnette never talked about himself

other than mentioning the get-rich-quick sweepstakes he was constantly

entering, recalled Ed Winstead, Peggy's husband.

Burnette, 77, died in his Cutten

home in June. He left his estate to Peggy and Ed's son, Gary.

Peggy and Ed came out to California to take care of Burnette's

funeral arrangements and to go through his possessions.

Burnette had a lot of possessions.

His home was filled with more than 400 video movies, hundreds

of photographs, a large collection of tin boxes and vintage whiskey

bottles.

Some of Burnette's photos are

stored in a 50-gallon drum at the Humboldt County Coroner's office.

Coroner Frank Jager said he plans to ship them to the Winsteads.

Some of Burnette's belongings were sold at an estate sale.

Steve D'Agati, a Eureka resident,

bought two photo albums and a stopwatch belonging to Burnette

at the sale. What caught D'Agati's eye was the writing on the

outside of the envelope that held the stopwatch.

W. L. Burnette, 3rd Mate,

S/S Badger State. Stop watch that was saved when S/S Badger State

was abandon (sic) in mid Pacific Ocean Dec. 26-1969 Approx. 1000

+11 zone time following a bomb explosion & fire in #5 hatch.

Ship abandon (sic) in storm. 26 men lost -- 14 men saved by Greek

MV Khian Star.

D'Agati did an Internet search on the SS Badger

State. He combed through the scrap books. He learned about the

ship, a munitions boat bound for Vietnam; how its crew worked

frantically to limit the damage when its deadly cargo came loose

in heavy seas; what happened when it started taking on water

and tiny lifeboats were lowered into the cold waters of the

North Pacific. D'Agati did an Internet search on the SS Badger

State. He combed through the scrap books. He learned about the

ship, a munitions boat bound for Vietnam; how its crew worked

frantically to limit the damage when its deadly cargo came loose

in heavy seas; what happened when it started taking on water

and tiny lifeboats were lowered into the cold waters of the

North Pacific.

"I thought it was a story

that should be told," D'Agati said.

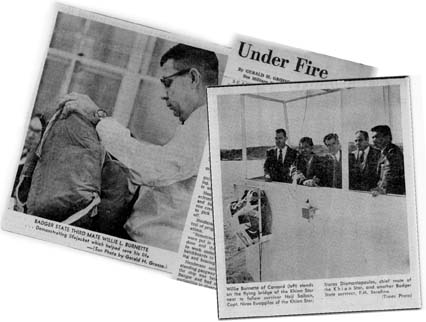

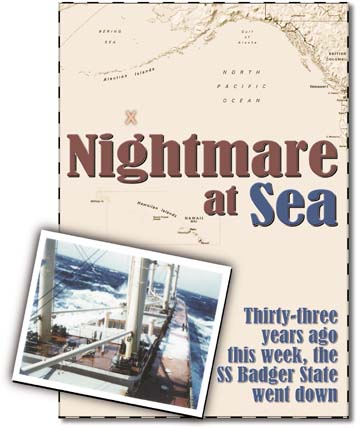

A forgotten disaster

But it's a tough story to tell.

Burnette's former shipmates, the ones who survived the wreck,

could not be found. Some have likely died, perhaps all. The only

record that seems to remain of one of the worst wrecks in the

U.S. Merchant Marine's shipping history are yellowed newspaper

clippings and a 44-page U.S. Coast Guard report.

Burnette's story makes reality

TV shows, such as Survivor, look like a holiday. He was

one of just 14 out of a crew of 40 aboard the Badger State to

survive. Of the 26 who lost their lives, only one body was recovered.

The cargo ship was hauling 8,900 bombs (with an estimated value

of $10 million in 1969 dollars) from Bangor, Wash., to DaNang,

Vietnam, in December 1969. The ship sank in rough seas about

1,600 miles from Hawaii.

It was one of four ammunition

ships making the nine-day voyage to Vietnam. All but the Badger

State reached their destination.

Those are the stark facts. But

they barely hint at the terror and desperation the crew must

have felt as, for almost a week, they battled to keep the Badger

State afloat in 20-foot waves and to somehow prevent the bombs

rolling underneath their feet from exploding.

How Burnette felt about being

one of the last men pulled from the ocean on Dec. 26, 1969, is

a mystery. The Winsteads said he never talked about it. He evidently

never wrote about it either, as no journals are to be found in

the possessions he left behind.

In 1969, Burnette was a Merchant

Marine. The Merchant Marines serve as support for the military

during times of war or national emergency, and with the quagmire

that was Vietnam deepening, 1969 was obviously a time of war.

The idea was cooked up by President Franklin Roosevelt in 1938.

He envisioned it as a way to get supplies to Europe during World

War II.

Burnette had been with the service

for most of his adult life, Ed Winstead said.

"He was dedicated to the

Merchant Marines," Winstead said.

One of the benefits of being

a Merchant Marine is the opportunity to travel the world. Burnette

had done that, Winstead said.

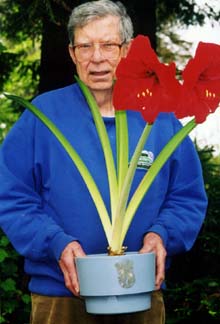

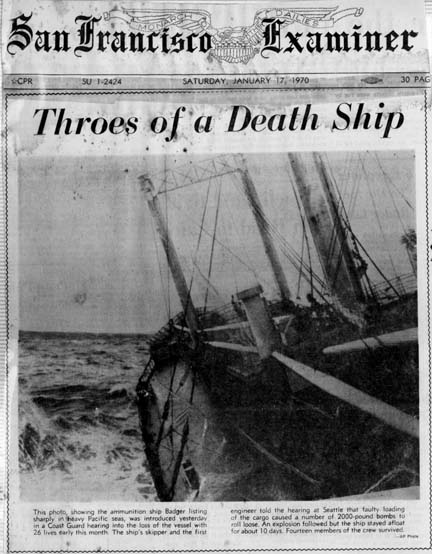

1970 article from Willie

Burnette's scrapbook.

Caption reads: "This photo showing the ammunition ship Badger

listing sharply in heavy Pacific seas,

was introduced yesterday in a Coast Guard hearing into the loss

of the vessel with 26 lives early this month.

The ship's skipper and the first engineer told the hearing at

Seattle that faulty loading

of the cargo caused a number of 2000-pound bombs to roll loose.

An explosion followed but the ship stayed afloat for about 10

days. Fourteen members of the crew survived."

Doubts about the

cargo

Undoubtedly his most perilous

experience began on Dec. 9, 1969, when the SS Badger State took

on cargo at the Bangor Naval Ammunition Depot in Washington State.

The ship was transporting the equivalent of 2,000 tons of TNT

to the U.S. Air Force in South Vietnam.

Bangor, near the Hood Canal,

had been the Navy's ammunition depot during World War II, the

Korean and Vietnam wars. (In 1973 the facility became the home

port for the U.S. Navy's ballistic missile submarine fleet.)

The Badger State was chartered

by the Military Sea Transportation Service. Commercial ships

were often chartered by the MSTS, a division of the U.S. Navy,

to carry almost all of the supplies used by U.S. forces during

the Vietnam War. The Badger State was originally commissioned

in 1944 as the USS Starlight, a troop transport ship.

Burnette was one of the crew

responsible for making sure the cargo was properly secured. As

he would later testify during the Coast Guard investigation,

the cargo in his view was solidly packed and shored. However,

testimony from other crew members cast doubt on whether longshoremen

at Bangor had properly loaded the cargo in the first place; it

was also claimed that shoring efforts conducted after the ship

hit bad weather were carried out by seamen who were not properly

supervised and who lacked special training for such work.

Before the ship left Bangor,

Capt. Charles T. Wilson expressed concern that the weight of

the cargo -- 5,000 tons -- was too small to give the ship a steady

ride. He asked for additional cargo -- at least 4,000 more pounds

-- but was advised there was none. The cargo ended up being spread

among several holds, and measures were taken to further

store and steady the cargo. Although depot personnel and the

ship's crew differed on how best to shore up the bombs, it was

determined that some measures, such as using metal bracing on

the 2,000-pound bombs, were unnecessary.

The cargo consisted of unfused

aerial bombs of 500-, 750-, and 2,000-pound size. In addition,

the Badger State carried 10,640 barrels of fuel oil, 611 tons

of water, nine tons of lubricating oils and 295 tons of lumber

to help secure the cargo while at sea.

After five days of loading and

inspections, the Badger State set sail the evening of Dec. 14,

1969. The ship's course would take it along a northern route

across the Pacific toward the Aleutian Islands. The ship would

then turn toward the southwest and head for the Luzon Straits

-- between Formosa, now Taiwan -- and the northernmost island

in the Philippines.

The bombs come

loose

On Dec. 15, the ship encountered

heavy seas about 1,500 miles northeast of Hawaii. With 15-foot

waves pounding the ship's hull, it became clear that this was

going to be an eventful mission.

The crew was told to shore up

the cargo to keep the ship from rolling. On Dec. 16, Capt. Wilson

ordered a shift in the ship's course southward in a bid to escape

the weather. The crew, however, was unable to comply because

the ship was rolling so severely -- as much as 45 degrees. To

make matters worse, the steering gear began to leak hydraulic

fluid. A 90-minute repair was conducted, during which time the

ship continued to roll violently. That evening, bombs in the

No. 3 hold came loose and began to shift. The crew worked around

the clock for two days to stabilize the moving cargo.

On Dec. 19 the ship was slowed

to 13 knots to allow the crew to mix cement and use it to patch

several small holes in the hull. Although some water was leaking

through these holes, the ship was in no danger of sinking. Once

the repairs were made, the problem was of no further concern

to the crew, according to the Coast Guard investigation.

By the time the ship reached

Adak Island (in Alaska's Aleutian Island chain, about halfway

between Seattle and Japan), where it was to change course toward

the southeast, the crew was working to shore up the cargo in

all of the holds.

Bombs of all sizes were now

moving about. As the day wore on and the ship's rolling continued,

Wilson wanted to take the Badger State in a more southerly route.

But Fleet Weather Central, the Navy's Pacific weather office

based in Alameda, Calif., told Wilson he should see improved

weather conditions if the ship maintained its westerly route.

But the weather didn't improve

and the Badger State continued to battle 20- to 40-foot seas.

Eventually, the crew could hear the sound of metal banging on

metal coming from cargo hold three. However, because earlier

efforts at stabilizing the cargo had effectively blocked access

to the hold, it was now impossible to get in and inspect it.

It wasn't long before all the cargo holds were in need of shoring

up, but there was little material left on board to use.

Wilson made the first of several

requests to sail to a safe port so that the cargo could be resecured.

He was told to head for Pearl Harbor, about 1,600 miles to the

southeast. Although the rolling began to subside, Wilson reported

bombs were still coming loose. He said an escort ship might be

needed should the situation aboard the Badger State deteriorate

further.

A black Christmas

Wilson and his crew never made

it to Pearl Harbor. In the early morning of Dec. 25, Christmas

Day, a storm that was not predicted passed directly over the

Badger State. Hurricane-force winds and violent seas began to

batter the ship.

The Badger State began to roll

heavily, tipping as far as 50 degrees (about the same as tilting

your head to get water out of your ear). The bombs in all the

holds came loose. Wilson was ordered to divert his course toward

Midway Island.

The SS Flying Dragon en

route from Japan to Long Beach, was sent to intercept and help

out. But by late evening on Dec. 25, strong gale-force winds

kept the Badger State from changing course.

Within a few hours a second

surprise storm hit the Badger State. The seas were so violent

that at times the ship was almost rolled onto its side. The ship

was getting hammered. A large wave damaged one lifeboat,

rendering it useless. The shoring and bracing that was supposed

to keep the bombs in one place began to fail. As they rolled

about, the steel noses of the biggest bombs -- the 2,000-pounders

-- began to pierce the hull. Lumber used to shore up the bombs

began to break and splinter. It was only a matter of time, Wilson

thought, before the bombs started going off.

Wilson ordered the crew to use

whatever nonflammable material was aboard to keep the bombs stationary:

sofa cushions, spare insulation, mattresses, rags, frozen meats,

spare life jackets -- all were tossed into the holds. The crews'

efforts worked for a short time, but the relentless rolling made

it impossible to keep the bombs motionless.

Crew members looking down into

the holds could see sparks from the bombs as they rolled across

the floor.

"Bombs were all over. It

was the most awesome sight I've ever seen in my life; like a

pit of deadly snakes. Every time a bomb would hit the side of

the ship I'd shudder," crewman James Beatty told Coast Guard

investigators.

Wilson saw the situation was

hopeless. Because of the violent pitching of the ship and the

efforts to secure the bombs, sleep was almost impossible. Wilson

himself had been up for four days. He sent out an SOS.

A fatal blow

Wilson's distress call activated

an alarm aboard the Khian Star, a Greek freighter headed for

Japan. The Greek ship was about 35 to 40 miles away from the

Badger State. Captain Evangelos Niros radioed he would assist

the Badger State. Still, Wilson altered the ship's course toward

Midway Island -- and away from the potential rescue ship -- evidently

deciding that the top priority was to make it to a safe port.

With

worsening weather conditions, Wilson ordered the crew off the

deck. Ten minutes after one more attempt to shore up the bombs,

one of the 2,000-pounders partially detonated. With

worsening weather conditions, Wilson ordered the crew off the

deck. Ten minutes after one more attempt to shore up the bombs,

one of the 2,000-pounders partially detonated.

Because the bomb did not fully

explode, it didn't set off a chain reaction that would have blown

the ship sky-high. But it was strong enough to blow all

the cargo hatches off, send burning debris onto the deck and

blow a 12- by 8 -foot hole in the starboard section of the hull.

"I was stunned, waiting

for the rest of the explosion. When you're riding on [thousands

of bombs] and part of it goes, how is it the rest doesn't go?"

wondered Steven Bordash, one of the Badger State's engineers,

during the hearing into the accident.

Expert testimony given at the

Coast Guard inquiry and contained within the agency's report

indicated that, "if the detonation were not of low order,

the most probable result would have been the complete destruction

of the vessel as the adjacent bombs detonated. Even the explosion

of the other 2,000-pound bombs would have resulted in the complete

destruction of the vessel's stern section."

Below

are some of the messages sent by Captain Wilson of the SS Badger

State to State Marine Lines (owner of the ship). The messages

were received by the SS Columbia Beaver that was 1,000 miles

from the Badger State's location.

"All hope

for further survivors now non-existent. "

"Five men that were staying on board with me/ Chief Mate

Leonard Cobbs/Second Mate Robert Ziehm/Third Mate William Burnette/Able

Seaman Ed Hottendorf/and FWT Sam Keneso assisted launching lifeboat

and seeing that all hands were clear. We took to the sea swimming

in an attempt to make the rescue ship. Three of us made it --

myself/third Mate and FWT. "

" I do not have the authority to destroy my own ship or

and I won't order it sunk now. It's a floating time bomb. " |

Abandon ship

Facing continued severe weather

and the possibility of additional explosions, Wilson ordered

the crew to abandon ship. Bordash shut down the engine room and

the crew threw on their life jackets. Thirty-five men climbed

into the starboard lifeboat. Fighting high winds and thrashing

seas, Wilson, Burnette and three others tried to lower the lifeboat.

A 30- to 40-foot wave, however, threw the lifeboat up against

the Badger State, causing electrician Konstantinos Mpountalis

to be seriously injured. He received a six-inch gash on his leg

when he struck the jagged hole created by the explosion.

Incredibly, as the lifeboat

dropped closer to the ocean, a 2,000-pound bomb fell through

the hole and landed in it. The men dove into the water as the

lifeboat capsized. Burnette, Wilson and the three remaining men

on the Badger State never saw what happened. They had no idea

35 of their shipmates were adrift in the high seas.

Burnette eventually saw some

men in the water on the starboard side of the ship, and threw

them life preservers, according to a Coast Guard report.

Attempts to launch inflatable

rafts failed as hurricane-strength winds blew the rafts out of

reach of the men in the water.

Burnette, Wilson and the others

donned life jackets, life preservers and jumped overboard

into 20-foot seas and 50-degree water.

Burnette would later testify

that had he only taken his life jacket he didn't think he would

have survived.

A valiant rescue

When the Khian Star arrived,

some men were clinging to the overturned lifeboat, while others

were trying to swim toward the rescue ship, or toward any object

they could hold on to. Many were simply swept away by the huge

waves.

Ioanis Kantzilakis, a crewman

from the Khian Star, jumped into the ocean to rescue a Badger

State crewman. But the crewman was already dead and Kantzilakis

could not bring the body aboard by himself.

A U.S. Air Force rescue airplane

arrived on the scene and attempted to drop six lifeboats, packaged

food, medicine and radios to the men. High winds swept five of

the lifeboats out of reach. But George Henderson, a Badger State

crewman, was able to grab hold of the sixth lifeboat and help

six men climb into it. Three were eventually saved by the Khian

Star.

The men who were in the water

suddenly found themselves fighting more than the seas as albatrosses

began attacking them. Like dive bombers, the large seabirds swooped

in and pecked at the men's eyes and heads. The men used their

fists to repel the onslaught. Even their life jackets started

turning on them. The agitation of the water was so intense that

the jackets rode up the backs of the men who were exhausted or

unconscious, pushing their heads down into the water. Many of

those who perished were found floating face down.

The Khian Star was able to rescue

eight men who were clinging to the capsized lifeboat. Five

others were pulled from the water -- Burnette and Wilson among

them. One man was found -- alive -- floating five miles from

the Badger State. The remaining 25 crewmen were presumed to have

drowned (a 26th died after being rescued).

Too dangerous to

salvage

The Khian Star, with its own

crew and the 14 Badger State survivors, headed for Japan.

The USS Abnaki, a Navy fleet

tugboat with an ordnance team aboard, was sent from Pearl Harbor

to try to salvage the Badger State and its cargo. Meantime, Air

Force and Coast Guard planes methodically searched an 8,000-square-mile

area for survivors, but never found any. The SS Flying Dragon

arrived on the scene and conducted its own search. The crew eventually

recovered the body of Badger State seaman John Kaleiwahea. By

Dec. 28, up to seven ships were searching for survivors. Coast

Guard pilots told of seeing an orange glow on the Badger State.

By the time the Abnaki got to

the ship, its crew was seeing flashes emanating from it. The

Navy decided not to make any attempt to recover the ship's cargo.

By Jan. 2, the Badger State began to sink. Fearing a large-scale

explosion, the Abnaki moved about a mile away from the Badger

State, and warned passing ships to steer clear. By Jan. 3, the

Abnaki withdrew to seven miles from the Badger State. Two days

later, the crew of the Abnaki recovered debris from the Badger

State, confirming that the ship, rather than exploding, had sunk.

Within months, an investigation

was begun. Burnette, Wilson and 11 other survivors testified

about a variety of things, including how the ship's cargo was

loaded and stored, the horrendous weather and the bravery of

the crew of the Khian Star.

A key issue, of course, was

the cargo -- did the bombs come loose because they were improperly

loaded in port and then inadequately shored up at sea? Or was

the weather so terrible that the bombs would have started rolling

around no matter what?

A 44-page report on the disaster

based on the Coast Guard investigation as well as one by the

National Transportation Safety Board came out almost two years

after the disaster. It cited a series of "causal factors":

the bombs, loaded on pallets, were buttressed in such a way that

if a single wedge or block came loose, a whole row of pallets

would be released; the lack of a full load of cargo made the

ship more vulnerable to rocking by waves; the unusual severity

of the storms of Dec. 25 and 26; the inability of Fleet Weather

Central to forecast those storms.

No single individual or group

was blamed for the catastrophe. While the report concluded that

the disaster may have been averted if Wilson "had returned

to port or sought shelter as soon as the cargo started to shift,"

his decision to continue the voyage after initial shoring efforts

proved successful was "reasonable." Throughout the

ordeal, his actions, as well as those of his crew, "were

in the best traditions of the sea," the report found.

A memorable estate

sale

As with any disaster, various

lessons can be drawn from this one -- a flippant one being never

get on a ship that's carrying bombs. Another lesson, one made

clear not by the disaster itself but by D'Agati's purchase, is

that you never know what you're going to find at an estate sale.

Burnette may have been the last

known survivor of the disaster. When he died seven months ago,

the story of the crew's desperate attempts to save the doomed

freighter could have faded further into obscurity. But D'Agati

appeared on the scene, intrigued by some writing on an envelope

that held a stopwatch and a couple of photo albums with their

old faded news clips and unmarked photos. And so the harrowing

story of the SS Badger State lives again.

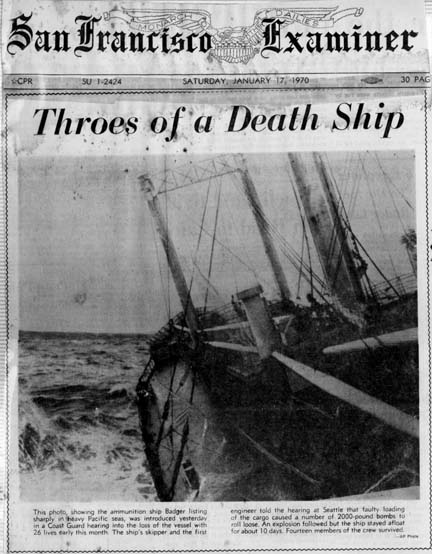

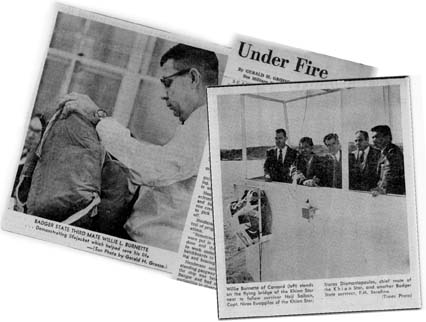

Below left, SS Badger Third

Mate Willie Burnette demonstrates the use of the lifejacket that

saved his life.

In the other photo, Burnette, far left, stands on bridge of Khian

Star with some of other survivors of the SS Badger State.

Fourth from the left in photo

below, is Capt. Evangelos Niros, M/V Shian Star standing next

to

Willie L. Burnette (3rd Officer, SS Badger State)

IN

THE NEWS | CALENDAR

Comments? E-mail the Journal: ncjour@northcoast.com

© Copyright 2003, North Coast Journal,

Inc.

|

IT DOES NOT APPEAR THAT ANYONE REALLY KNEW William

Burnette. [ photo at right,

2002] Those who were acquainted

with him said he was a loner, never married.

IT DOES NOT APPEAR THAT ANYONE REALLY KNEW William

Burnette. [ photo at right,

2002] Those who were acquainted

with him said he was a loner, never married. D'Agati did an Internet search on the SS Badger

State. He combed through the scrap books. He learned about the

ship, a munitions boat bound for Vietnam; how its crew worked

frantically to limit the damage when its deadly cargo came loose

in heavy seas; what happened when it started taking on water

and tiny lifeboats were lowered into the cold waters of the

North Pacific.

D'Agati did an Internet search on the SS Badger

State. He combed through the scrap books. He learned about the

ship, a munitions boat bound for Vietnam; how its crew worked

frantically to limit the damage when its deadly cargo came loose

in heavy seas; what happened when it started taking on water

and tiny lifeboats were lowered into the cold waters of the

North Pacific.

With

worsening weather conditions, Wilson ordered the crew off the

deck. Ten minutes after one more attempt to shore up the bombs,

one of the 2,000-pounders partially detonated.

With

worsening weather conditions, Wilson ordered the crew off the

deck. Ten minutes after one more attempt to shore up the bombs,

one of the 2,000-pounders partially detonated.