by Wally Graves

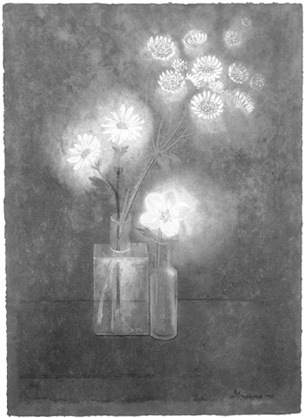

Winter Bouquet #4

(seedling chrysanthemums, astrantia and helebrore), 1976.

WHAT'S TO BE SAID of an "internationally famous" painter who lives in the woods back of Loleta?

Locally, Morris Graves has followed the dictum of Igor Stravinsky, "If we do not support the young, there will soon be no old." He's been a quiet but active friend of North Coast artists and writers, beginning with sculptor Melvin Schuler, and continuing with Floyd Bettiga, George Presson, John Swingdler, Bob Benson and many other younger painters.

Five years ago Morris donated a major body of 20th century and ancient art to the Humboldt Arts Council's permanent collection. This gift, exhibited as "Sharing a Private Vision," helped spur the council's current move to its new center in Eureka's former Carnegie Library.

Major shows highlighting local and regional artists to which Morris, assisted by Loleta resident Robert Yarber, has given a boost include "From the Center" in 1989, "The Northwest School, a sense of place within" in 1993 and "Three Times Three" in 1994.

During his three decades on the North Coast, Morris' mind and hand have produced flower paintings which, according to longtime Christian Science Monitor art critic Theodore Wolff, are the "finest and most radiant flower paintings anyone has seen" since the days of the French Symbolist painter Odilon Redon (1840-1916).

Another critic, John Yau, declared his flower paintings "wholly unlike any other contemporary painter's treatment of flowers." Whereas Georgia O'Keeffe and Andy Warhol knew how to make flowers become paint, "Graves knows how to make paint become flowers" (echoing Pablo Picasso's: "There are painters who transform the sun into a yellow spot, but there are others who, with the help of their art and intelligence, transform the yellow spot into a sun.").

As recently as Oct. 26 art critic Regina Hackett wrote of Morris in the Seattle Post-Intelligencer, "Even when he paints or draws something as universal as flowers, they are his flowers, infused with the rough grace and force of spirit he brings to all things."

Just the other day Morris said to me, "My focus is beauty. We live in a world of opposites tugging at us. Beauty alone has no opposite. Some 50 years ago I wrote to my agent Marian Willard in New York, 'I should use beauty as an opiate and if I can pull it out of nature and hint at it in paint then I should, and hand it as an opiate to any who will have it.'

"Opiate," he explained (long before the word "psychedelic" came into currency), "is that which broadens and deepens what the mind can accept, and in this deepening of the viewer's potential experience, art leads toward an equilibrium, toward freedom from the world of opposites. Viewers must bring a matching input to widen and deepen their life-enhancing element, or their lack of it."

I reminded Morris that William Blake once wrote, "A little flower is the labor of ages."

"That's fine."

"And," I went on, "our friend Kenneth Rexroth once said that the value of poetry in education is that it produces a deeper and wider and more intense response to life."

"That's good."

Then we talked about the French Symbolist poet Charles Baudelaire's comment in a prose poem titled "Enivrez-vous": "In order not to feel the horrible burden of Time that breaks your shoulders and bends you to the ground, you must be continually inebriated. But inebriated on what? On wine, on poetry, on virtue -- whatever you wish. But get inebriated."

"Inebriated on beauty," Morris added.

Morris's earliest paintings were of birds: "Blind Bird," "Bird Singing in the Moonlight," "Spirit Bird." He was -- in the words of Regina Hackett -- "the youngest and most famous of the group that came to be known as the Northwest School, the first (and last) group of Northwest artists to establish an aesthetic identity for the region."

Commencing with a show at New York's Museum of Modern Art in 1942, his mystical (or, as some would say, metaphysical) paintings were added to major private and public collections throughout America and have been exhibited around the world. He was awarded a Guggenheim Fellowship in 1946, the first Duke and Duchess of Windsor international art award in 1954, a grant from the National Institute of Arts and Letters in 1956 and the following year, upon his nomination by the writer William Faulkner, was elected to the Institute.

Though not a public speaker, in 1987 as a guest of the government of India, Morris addressed the topic "Transition: a continual renewal" at an international seminar in New Delhi.

His art is the subject of half a dozen full-length books, and his paintings and constructions have inspired dozens of poems and responses by such writers as Lawrence Ferlinghetti and the musician-poet John Cage.

Comments on this story? E-mail the Journal: ncjour@northcoast.com

© Copyright 1996, North Coast Journal, Inc.