|

by ARNO HOLSCHUH

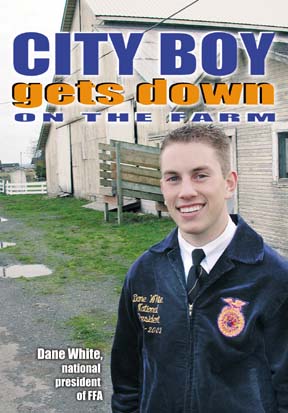

GROWING UP, DANE WHITE ALWAYS HAD a soft spot in his heart for farming. "I loved the lifestyle, the hard work, the dedication you have to have to the job," he said. Which is not to say that White has ever really lived on a farm. The recently elected national president of the 457,000-member Future Farmers of America was born and raised in the urban environment of Eureka. His father is a heavy equipment operator and his mother a pharmacy technician. In his own words, he is "a city boy." And the 20-year-old thinks that's perfectly appropriate for an FFA president. Agriculture is no longer just "cows and plows," he says. It's a complex industry that needs skilled individuals to lead research, marketing and processing -- and not all of those individuals will have grown up on a farm. "Agriculture is romanticized as an industry," White said. "People see us as farmers standing in the field with a setting sun, cow and chicken." For most of the people who will find jobs in agriculture, that image is "completely old-fashioned and irrelevant." But hands-on farming still exerts a hold over White's imagination. Ask him about the dairy cattle he raised as a high school student and he will tell you he was "passionate" about them. "I loved raising cattle," he said. It is the apparent split in White's focus -- part city, part country -- that makes him a good fit in today's FFA. The changing agricultural industry requires a different kind of FFA leader --White represents that change. [Below, Dane speaks at a 1997 FFA barbeque in Eureka.] ![[photo of Dane giving speech at FFA gathering]](cover1213-speech.jpg) White's first exposure to agriculture came at the home of his great-uncle and aunt, Janet and Bruce Louis, in Redcrest. White's first exposure to agriculture came at the home of his great-uncle and aunt, Janet and Bruce Louis, in Redcrest.

"They had beef cattle and some small garden crops," he said. He would spend weekends at the farm marvelling at the cycles of birth and growth the cattle went through. "When I was a kid, I really enjoyed that aspect of it. I was always fascinated." But he would also always return to Eureka after the visit, leaving his fascination behind -- up until a scheduling accident his freshman year at Eureka High. "I had an ag leadership class that I didn't want, but I suddenly ended up with it on my schedule. I couldn't get into the counseling office to change it, so I went into class." What he found was his future. "There were all these juniors and seniors in there, people who were officers of the FFA and active members in the organization." (In California, students who take agriculture classes automatically become FFA members, but not all become active members.) "About a week later, I had the opportunity to change out of the class. I didn't, because it turned out I really liked what we were doing in ag leadership." And he was good at it -- very good. Agricultural leadership classes center on "soft skills" like written communication or public speaking. White proved to be friendly, articulate and quick-thinking: The ideal FFA leader. "He's very bright and likes to be in front of people," said Sandy Lovald, one of White's two high school ag teachers. "He remembers names and is quick-witted, so the leadership aspect of FFA lent itself to him." He became very active in the FFA, participating in a range of extracurricular activities. There were contests that tested his knowledge of parliamentary procedure and others for his ability to deliver a prepared speech. White even took part in a nerve-wracking activity called extemporaneous public speaking. Participants are given a randomly selected topic and 20 minutes of preparation time, after which they give a four- to six-minute speech to a panel of judges. Even the cool and collected White admitted, "It's pretty difficult." It is also good training, he said. "You don't see many 16-year-olds who have the ability to look a 40-year-old in the eye and carry on an intelligent conversation," he said. After speaking to a panel of judges about an unfamiliar topic, White could look almost anyone in the eye. He got a chance to use those skills when speaking in front of community groups like Lions and Rotary clubs, "just bringing our perspective to what they do." At the same time White was learning how to communicate effectively under pressure, he was also learning the nuts and bolts of agricultural science. "In ag science, you learn the practical aspects of the industry -- biology, basic anatomy, soil science, earth science, the weather and all the things that affect agriculture. "It's similar to regular science, except that instead of looking at a frog, you're looking at the reproductive system of a pig," White said. The extracurricular activities associated with FFA's agricultural science program let White live out his childhood fantasy of raising cattle. During his high school years, White used local dairy farms to raise 10 cows from calves to "springers," when the cows are having their first calves and beginning to produce milk. "That was very worthwhile," he said. "That was when I was really able to kind of immerse myself in it practically. I could see it first-hand and it gave me a richer appreciation" for the process.

![[photo of Dane with calf]](cover1213-calf.jpg) At right, Dane with Lola, one of the cows At right, Dane with Lola, one of the cows

he raised on a friend's dairy farm in 1998.

White also honed more esoteric farming skills. He not only learned how to appraise dairy cattle at contests across the state, he learned to judge the dairy goods they produced. "I did dairy products judging during my sophomore year," he said. "You get to taste milk, but it has these off-flavors in it and you have to say what off-flavor it has." If, for example, pennies were put into the milk before the tasting, it would have a metallic taste that White would have to identify. The real-world application of this bizarre-sounding exercise is in quality control. "What if the milk was picking up the taste of the pipes it went through?" he asked. A dairy farmer would need to be able to identify anything suspicious in his milk and trace it back to its source. But while White did well at the practical aspects of agricultural education, it was his obvious ability to articulate what he learned that made him a rising star in the FFA. After years of preparation, he went to the national FFA convention in Louisville, Ky., in October to run for national office. His presentations on agricultural issues so impressed the judges that they not only tapped him for the national committee -- they asked him to lead it. "In the committee's eyes, I just had the most to give," he said. In return for his abilities, White gets a chance to travel the country and the world, all-expenses-paid, for the next year as a representative of American agricultural education. He'll put off college for a year, but it's worth it, he said. After two solid months of training at FFA headquarters in Indianapolis, which White started in mid-November, he will begin visiting the group's industrial sponsors. Then he begins his tour of state FFA conventions, where he will present keynote addresses and workshops. In February, the new FFA president will attend a convention on global agriculture in Japan and take a tour of Japanese agriculture. It's an itinerary that has him travelling more than 150,000 miles in about 300 days. And at the end will be what White already imagines as the crowning achievement -- next year's national convention. "It will be our 75th convention and we're really excited, because they've saved up tons of money for us." The high point, he said, will be convention's keynote speech delivered by President Bush. [Below, Dane at Redwood Acres] ![[photo of Dane with cows]](cover1213-show.jpg) Underneath White's giddy excitement at the prospect of a year on the road is a steady determination to improve the nation's agricultural industry. Underneath White's giddy excitement at the prospect of a year on the road is a steady determination to improve the nation's agricultural industry.

"Our purpose in the FFA is to send students out who have the skills to become leaders in the industry," he said. The advantages to a farmer of learning about his livestock's anatomy and health are obvious -- he or she will better know how to manage their livestock or crops. But there are also less direct benefits to agricultural education. "If a person working in public relations for a large agricultural corporation was in FFA, they will have both better interpersonal skills and more knowledge to draw on." White said the FFA trains high schoolers for more than 250 careers related to agriculture. He is an example. He doesn't expect to run a farm, he wants to teach agriculture. "Or maybe someone wants to run for elected office later in life. FFA would be a way for them to learn about how agriculture works." And agriculture will continue to face some serious questions, White said. The increasing controversy over the use of genetically modified crops is an example. FFA's role is to provide an open forum for agricultural issues to be discussed. Genetically engineered crops present "a potential for agricultural growth, but they also present a potential for consumer backlash," White said. "Consumerism is a big part of agriculture. We have to produce what people will eat. If people won't eat genetically modified crops, we can't produce them. "We don't support people eating them, but we don't oppose it. We support education," he said. White may well face other ag-related hot button issues while on the public relations trails across the country in 2002, topics such as antibiotics use on cattle or the perceived consolidation of small family-owned plots of land into large corporate farms. Dane answered all those questions by explaining the FFA is an expressly nonpolitical organization that does not take official stances on controversial issues but supported education to foster an intelligent debate. One thing for sure, White said, "Having literate, well-versed people in the industry who can communicate our message will strengthen it." At least one of those leaders will be a city boy from Eureka.

IN THE NEWS | ARTS! ARCATA | CALENDAR Comments? E-mail the Journal: [email protected]

© Copyright 2001, North Coast Journal, Inc. |