|

story & photos by ARNO HOLSCHUH

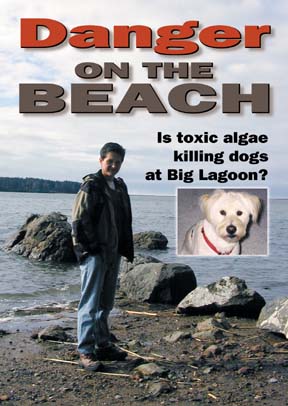

HEATHER MULLER OF SACRAMENTO

loved her dog Ernest, a fluffy white 6-year old mutt, and Ernest

loved the outdoors. [in

above photo]

So when Muller left the confines

of the big city to visit the open spaces of Humboldt County,

she always took Ernest along. Muller normally camped at Patrick's

Point, but this year she decided to look for another spot --

for Ernest's sake. "They're not too dog-friendly at Patrick's

Point," she explained.

In late July she chose the county

campground on the shore of Big Lagoon and decided to do some

fishing. The clerk at a nearby tackle shop told her there was

a secluded beach on the north side of the lagoon where she might

have luck with steelhead.

When she arrived at the gravelly

beach, she found something strange in the water --foul-smelling,

blue-green foam close to shore. Muller, who described herself

as "totally paranoid" about the health of her pets,

asked two nearby windsurfers if the substance was harmful to

dogs.

"The lady said it was just

an algae bloom -- nothing to worry about," Muller said.

So she let Earnest loose to do what dogs do best -- frolic in

the water.

Later that night Ernest began

vomiting, but Muller wasn't worried. "In my experience,

that's what dogs do -- puke."

Twelve days and more than $1,000

in vet bills later, Ernest died. First he stopped eating, then

he stopped drinking water, then she took him to the vet where

he was diagnosed with liver failure. Shaking, dehydrated and

in pain, Ernest was made as comfortable as possible until Muller

finally made the most difficult decision a pet owner can: She

put him down.

Ernest's death -- and the deaths

of at least four other dogs in the county this year -- can almost

certainly be traced to a rare phenomenon called blue-green algae

poisoning. Actually a photosynthetic bacteria, blue-green algae

(or cyanobacteria) are present in many bodies of fresh or brackish

water. Normally they exist in such low concentrations that they

cannot be detected without laboratory equipment. But when certain

conditions are right, they experience an exponential growth in

population, reproducing until they form a layer of sticky, smelly

scum.

Even such a population explosion

-- called a bloom -- is not normally dangerous. Only certain

strains of the bacteria produce toxins, and then only when they

are decomposing.

It is impossible to prove beyond

a doubt that blue-green algae caused the dogs' deaths because

a conclusive tissue test does not exist. But a consensus is growing

-- among private veterinarians, state and county officials, and

the owners of the deceased dogs -- that it is by far the most

likely cause.

What has Muller and other dog

owners angry is not that the naturally occurring algae exists.

It is that neither county nor state officials put signs up after

Muller warned them that something was seriously wrong at Big

Lagoon.

Muller, a public relations professional,

spent a good part of what remained of her vacation crawling up

and down the chain of command in county parks, state parks and

the Department of Fish and Game. Throughout the month of August

she tried to get some agency to simply alert other dog owners

at the beach. She was repeatedly rebuffed. In the meantime, other

dogs were meeting the same fate as Ernest -- liver and kidney

failure, likely caused by the ingestion of blue-green algae.

Muller's first stop after Ernest

was diagnosed July 28, while he was still alive, was the campground.

She spoke with the camp host, who put her in contact with a county

parks ranger.

"I gave him a copy of a

toxicology report and he said he would take it to his boss,"

Muller said. The next day she received a note saying that state

and county parks, which share jurisdiction over Big Lagoon, had

decided to post the signs.

"Shortly thereafter, Ernest

died, and I went down to see if in fact the signs were up --

and they were not." When Muller called county parks she

was told that the county was going to wait for approval from

state parks so they could coordinate their actions.

State parks, in turn, went to

the state Department of Fish and Game for advice. Fish and Game,

Muller learned, had recommended against putting signs up.

"I called Fish and Game

and talked to a woman named Karen Kovacs. I asked her what the

deal was," Muller said.

"When we initially got

the call on this, it was so out of the blue I had never even

heard if it," said Kovacs, a senior biologist supervisor

with Fish and Game. Kovacs said after county parks related the

story to her, she contacted Humboldt State University scientists

and Fish and Game veterinarians. According to Kovacs, they said

there was no information to indicate that the blue-green algae

was likely to cause injury to wildlife.

"The question was, do we

have any proof? And at that time, there wasn't any," Kovacs

said. Given that warning signs might have negative side effects,

such as scaring away tourists, she suggested that warning signs

not be posted.

"Do we want to concern

people unnecessarily? There are a lot of people who recreate

up at Big Lagoon," she said.

In fact, Kovacs said, she has

yet to be convinced that blue-green algae was the cause of death.

"There is not enough there

so far to convince me that it is [blue-green algae poisoning],"

she said. "The only thing for sure is that [the deaths]

occurred. Is that enough to show there's a smoking gun called

blue-green algae in Big Lagoon? No."

But the most important thing

to realize is that the decision was never hers to make, Kovacs

added.

"I can't tell them what

to do," she explained, because Fish and Game does not have

jurisdiction over the beach. Kovacs only becomes involved if

wildlife is injured, and there has been no evidence that has

occurred.

"The Department of Fish

and Game is a resource agency for the state of California. What

purview do we have over domestic dogs?"

Kovacs' early August recommendation

may not have had the power of law, but it was enough to stop

the state and county parks officials from putting warning signs

up.

Bob Anderson, the state's supervising

ranger for Big Lagoon, said after he spoke with Fish and Game,

"I wasn't really sure what we had. We didn't really know

if this blue-green algae was really the cause or not."

Anderson asked his superiors

how to proceed. "We were told to monitor it and not put

any signs" unless it was clear that blue-green algae was

harming animals at Big Lagoon.

Of specific interest were wild

animals. "It was a matter of monitoring the area to see

if we found any [injured] wildlife and we never did."

Again the issue of jurisdiction

complicated matters.

"State parks owns quite

a bit of land around the lagoon but we don't own anything on

the water itself," Anderson said. "I believe that's

Fish and Game [jurisdiction]."

"If we had had some conclusive

evidence, that would have helped. We would have put the signs

up if we had known for sure."

What the state parks needed

was proof and proof was hard to come by. Because the toxin is

unidentifiable in tissue samples, you can never conclusively

say it has caused a dog's death. Evidence can only be collected

from the periphery -- the dog's symptoms, the weather and the

appearance of the substance. All of those seemed to point convincingly

to blue-green algae. But to a scientific mind, those factors

were just so much circumstantial evidence.

"I don't know that anyone

ever established that it was blue-green algae that caused those

dogs to die," said Frank Shaughnessy, who teaches biology

at HSU.

Shaughnessy said that while

there is enough evidence to make the blue-green algae poisoning

scenario plausible, there wasn't enough to reach a conclusion.

He looked at samples from Big Lagoon and found blue-green algae

present -- but even that was not conclusive.

"These organisms will `bloom'

and some of them are known to be toxic, yes. But there are a

whole bunch of strains that are quite beneficial to our environment,"

he said. Other strains, like spirulina, are even eaten by humans

as a health food.

There are some indicators that

this may be a strain that usually does not flourish in Big Lagoon.

The lagoon did not breach in the winter of 2000-2001, so the

normal exchange of salt water from the Pacific and fresh water

from the streams feeding the lagoon never took place. The lack

of breaching also meant that the outgoing steelhead run was trapped

in the lagoon, contributing an excess of nutrients to the water.

An excessively fresh, rich water

supply may have caused a strain of blue-green algae always present

in background levels to explode. Put another way, if there had

been a freshwater-friendly toxic strain, this year was its chance

to shine.

"That could be the correct

scenario," Shaughnessy said, but still doubts remain.

"The bacteria needs to

be looked at and identified all the way down to species and strain"

in order to reach a scientifically valid conclusion about its

potential danger.

However, outside the realm of

science, a different standard should apply, Shaughnessy added.

Signs should be posted "just to err on the side of being

cautious." And if there is a danger to dogs, there is a

potential danger to humans as well, however small.

"I would suggest that dogs

are vertebrates and so are we. We've got livers," he said.

Muller was becoming increasingly

frustrated trying to convince the authorities of the argument

to err on the side of safety. Then mysteriously, in the middle

of August, the bloom seemed to clear.

"Bob Anderson calls me

and leaves a message saying the bloom has cleared, they're not

going to be putting any signs up at this time, and they will

continue to visually monitor the water," Muller said. "That's

when I said to hell with it and went home."

What neither Muller nor the

parks administration knew was that the algae is very elusive;

visual monitoring is not enough to conclude the bloom has cleared.

Assuming blue-green algae had

caused the dogs' deaths, it would be almost impossible to tell

when the danger had abated, Shaughnessy said. "If the bloom

were completely gone, there wouldn't be a problem, true. But

I would be doubtful that the bloom was completely gone.

"What's probably happened,"

he said, "is the population number has dropped down to a

lower level so you don't see it or smell it when you walk along

the water." That means it could come back at any time.

What's more, the algae can drift

into coves and other hard-to-spot areas and form high concentrations

there. Sometimes particles will sink to the bottom, where they

are difficult to detect. "There can be hot spots,"

he explained.

The only way to tell conclusively

would be to take hundreds of water samples, each of which would

cost about $70 to process. And because no government agency was

even clearly responsible for the situation, there was no one

to pay for that testing.

Maggy Herbelin and her husband,

Charlie [in photo at left]

had just returned from Japan when

their dog was poisoned at Big Lagoon Oct. 13. Charlie, an avid

windsurfer, was eager to get back onto the water with his best

buddy, an Australian shepherd-English setter mix named Wabi.

[in photo below right] Maggy Herbelin and her husband,

Charlie [in photo at left]

had just returned from Japan when

their dog was poisoned at Big Lagoon Oct. 13. Charlie, an avid

windsurfer, was eager to get back onto the water with his best

buddy, an Australian shepherd-English setter mix named Wabi.

[in photo below right]

"That evening, we went

out to dinner with some friends and Wabi threw up in the car,"

Herbelin said. "The next day she was off her feet and that

night she started throwing up blood." The couple took Wabi

to an emergency clinic, where the dog was rehydrated and diagnosed

with liver cancer.

The next day, their veterinarian

told them he was curious and wanted to send blood samples to

a lab for analysis. When the results came back later that day,

they confirmed that Wabi's liver had been seriously damaged.

By that time, the dog was dead.

"When I saw that report,

I said, `Let's do an autopsy,'" Herbelin said. "[The

vet] said OK, because a couple of weeks prior he had another

dog come in with the same symptoms." When the results came

back, they indicated Wabi had probably died of blue-green algae

poisoning.

Herbelin was already on the

case. As chair of the Humboldt Bay Watershed Advisory Board,

she was familiar with water safety issues and wanted someone

to test the water at Big Lagoon. She sent samples to Shaughnessy,

who confirmed the presence of blue-green algae. Herbelin was already on the

case. As chair of the Humboldt Bay Watershed Advisory Board,

she was familiar with water safety issues and wanted someone

to test the water at Big Lagoon. She sent samples to Shaughnessy,

who confirmed the presence of blue-green algae.

"I called Fish and Game

that day, where I got a runaround," Herbelin said. "I

was told they had no interest in looking into the matter at all."

But shortly thereafter, someone

finally did develop an interest. Brent Whitener, who works with

the county Health Department's vector control unit, was at the

Big Lagoon county campground Oct. 22 checking out a possible

case of rabies when he heard about something odd.

"I was advised that the

campground host at the park had lost his dog. That's when I began

my investigation," he said.

His first stop was to call the

local veterinarians, from whom he was able to confirm that not

one but at least five dogs had died after swimming in the lagoon

-- and the blood test results all showed liver damage.

It was enough to convince Whitener.

"The people who owned the

dogs said the dogs didn't have an opportunity to eat poisonous

mushrooms. They seemed to swim in the lagoon, and since they

were water dogs they wanted to lick and groom themselves when

they got out, quite literally eating the algae."

Oct. 25, just three days after

Whitener first learned of the problem, the county public health

branch posted signs on the county beaches at Big Lagoon. Nov.

9 state park officials agreed to allow the county to post signs

at the state end of the lagoon -- where the poisonings were occurring

-- although they declined to post signs themselves.

![[text of warning sign] WARNING: BLUE GREEN ALGAE PRESENT IN BIG LAGOON Avoid contact with the water. Presence of blue green algae in Big Lagoon during this fall season can result in buildup of toxics in the water to dangerous levels. Small coves and inlets of the lagoon where the algae collect are especially prone to higher levels of these toxins. Children and pets in particular should avoid these areas, not ingest the water, or consume or handle the algae. Questions or comments? Please contact: Humboldt County Public Health Branch Environmental Health Division, 445-6215](cover1129-warningsign.jpg)

Why did five dogs have to die

in order for signs to be put up? The answer lies in a second,

larger question: Who is responsible for the welfare of domestic

animals?

It isn't public health, according

to Whitener.

"What we have here is a

veterinary health threat rather than a [human] public health

threat," he said. "The nature of blue-green algae is

to lay up on the shore with a bad smell and a pond-scum appearance."

Because of how distasteful the stuff looks and smells, humans

are not likely to ingest it.

The only reason Whitener suggested

posting signs was because of the severity of the situation. "We're

not dealing with an issue that would typically be public health.

We were so taken aback by the nature of this that we decided

to break from our normal profile and at least put up signs."

Pete Peterson, a state veterinarian

charged with monitoring livestock diseases, told the Journal

in an interview in Arcata last week, "Blue-green algae

is a grey area of public safety." He didn't initially get

involved because no livestock was affected. It was frustrating

for him, he said, because as the summer turned into autumn, he

was hearing from more private small-animal veterinarians that

something was very wrong.

"We had what we call a

cluster -- an unusual pattern or number of deaths," Peterson

said. Trained to spot clusters in livestock, Peterson knew one

when he saw it with the dogs. "Same locale, same circumstances,

same history, same clinical pathology."

"Once you have a cluster,

it's an indication something is legitimately there."

But it didn't matter -- there

was no livestock involved. Peterson may have been concerned,

but he wasn't responsible to do something.

"I hope [the state] would

have someone to take care of concerns like this," said Jeri

Oliphant, the veterinarian who treated Ernest. "If there

is a toxin making pets ill, especially deathly ill, then someone

should take responsibility for that.

"Was this a collapse of

the system? I don't think so. They don't have a system."

IN

THE NEWS | ARTS ALIVE! | CALENDAR

Comments? E-mail the Journal: ncjour@northcoast.com

© Copyright 2001, North Coast Journal,

Inc.

|