HE'S BEEN HOOKED ON CLASSICAL MUSIC EVER SINCE he was a lad in knee britches, and today this cherubic-faced 64-year-old would seem to have found the best of all possible worlds in running Berliner's Cornucopia in Eureka, where he can listen to whichever classicist he likes -- from Bach to Tchaikovsky -- all day long.

Just don't suggest he must be doing well financially.

"Selling classical music?" Leon Berliner asks, looking at you as if you must have gone bonkers. "Nobody likes classical music. It's too bad; they don't know what they're missing.

"But consider this," he instructs. "In 1960, 15.5 percent of our (national) record sales were classical music; in 1997, it was 3 percent; this year it's 2.4 percent. So you're talking about a product that, for one reason or another, has lost its enticing glamor.... People don't have the patience, or, you know, it's not immediate gratification.

"You have to listen to a profound piece more than once before it becomes the wonder that it is, and people don't do that in their entertainment anymore. They want sound bites. They don't want to sit down for a while and listen to a contribution by an artist of 200 years ago that could move them if only they allowed the music to do so."

Berliner's Cornucopia store in Old Town Eureka.

Berliner's Cornucopia store in Old Town Eureka.

Yet against these daunting odds, come January Berliner will start his 16th year in the business. For approximately the first half of that time, his shop was on F Street, between Third and Fourth streets, where the Japanese restaurant Kyoto is now. With the help of his poker-playing buddies (another story, which we'll get to) and other friends, he was able to relocate over one weekend in March 1993 to his present location, at the corner of F and Sixth streets, which he rents from next-door neighbor Dalianes Travel Service. It offered more parking and more shop space for the used books he carries along with musical records and compact discs.

Besides the classical music, he carries American folk, Broadway and jazz. But no pop, no rap, no rock and no Country Western.

"You know," he remarks one day, "we're not by any means going to get rich doing this, but it is occupying my time, and I think it does fill a certain culture vacuum."

Berliner and his wife, Diana, who has been a teacher at Eureka High School going on 28 years and also teaches at Humboldt State University (her specialty is students with mental and physical disability problems), have decided to close shop as soon as it loses money. So far, that hasn't happened. "The pathetic part," Berliner quips, "is that I make so little money here that I get my full Social Security check."

Facing daunting odds is not exactly new in Leon Berliner's life. As a boy of 5 he was uprooted with the rest of his family his mother, a sister, Elvire, and his grandparents from their home in Antwerp, Belgium, and began a trek by boxcar with other Jews fleeing into France to escape the approaching armies of Adolf Hitler.

Berliner remembers going through five concentration camps in France, before his mother managed to arrange his escape. There were more than 200 concentration camps in France, Berliner relates. The French, he notes, "collaborated with the Germans, and took all the Jews and Gypsies, and Spaniards who had come from Spain pursued by the Franco forces. I actually ended up learning Spanish in those camps." The camps in France were holding pens, until their inmates could be shipped to the extermination camps in Germany.

"People died there; they died of malnutrition and disease, but they weren't exterminated. That took place in Germany."

It was from the camp at Rivesalte, in southern France, that Berliner's mother made arrangements for her son's escape. (She had earlier managed to get his older sister out.) An English nurse was to seduce a guard, and on the guard's disappearance Berliner's mother told him to "run, run, run, and don't stop." He followed the directions until he was picked up by a French truck driver and wound up, through the help of a French underground group trying to save children from the Nazis, staying with the family he knew as his godparents in the French village of Condon.

"They baptized us, so that we wouldn't be Jewish anymore," he recalls. Not that he denies his Jewishness; it is with organized religion he has a problem.

In one conversation, he tells me: "I identify as a Jew.... And because I had to deal with the fact that I've been taught for a lengthy period of time that Jews killed Christ and I loved Christ and because I went into a church and I have to take off my hat, and then if you go into a (Jewish) temple you have to put on a hat, I started to ask myself questions about God. What kind of god would have some people put on a hat or they don't get service, and what kind of god would have them take off their hat?

"Is there more than one god? So I came to the conclusion that if there is or isn't a god, he's confusing me....

"But I did learn that God makes it awfully difficult for people to get along with one another.... Religion, from what I learned about Ireland, from what I learned about the Middle East, from what I learned about all the varied plans of Protestantism starting with the 30 Years War, I learned that religion played a kind of role that was in the opposite direction of mankind getting along with one another. Therefore, I am not religious."

It may not be amiss, however, to say that he has found his religion in music. And that occurred, appropriately enough, at the end of World War II. An aunt and uncle who had managed to stay in hiding throughout the war, got word that nephew Leon, then 10 years old, was in Condon. They took him back to Brussels, where a friend of theirs, an artist, wanted to do a sculpture of his head, of this boy who had survived the horrors of Nazism.

"But I couldn't sit still," Berliner recalls, "and he's having a hell of a time trying to get my head done. At one point, he's just exasperated and he says, `Here, listen to this.' And he takes this black box (a record player, of course), winds it up, and takes this black-looking circle, and he puts it on, and then puts down the arm (with the needle), and then it goes: `Ta-ta-da-dum...'" The unmistakable opening notes of Beethoven's Fifth Symphony.

"Fantastic!" he exclaims. "And that's how I got seduced to music."

(Berliner has since learned that the sculpture wound up in a museum in Jerusalem. He was also to learn that his mother, whom he had last seen in Rivesalte, was among those who died in the infamous Nazi crematorium of Auschwitz.)

Berliner draws a selection from his music collection. By him is the photo of his boyhood sculpture.

At war's end, he would spend time in orphanages, one in Belgium and the second in Boston, before getting a degree in international relations from CCNY City College of New York and later, again appropriately enough, a master's degree in rehabilitation counseling.

It melded with his wife's educational leaning.

Diana Berliner (née Laster) remembers that they had known one another "glancingly" to begin with, and "actually met and talked to one each other in an education class" at CCNY. They had "a terrible teacher," she says, so she and Leon "sat in the back of the class and played `Battleship' and `Hangman.'" They were married in New York in 1960, and have two children, Gwen and Larry.

Leon and Diana Berliner.

Leon and Diana Berliner.

Redwoods United, in fact, honored Berliner Nov. 12 by dedicating its new wood production facility to its founding executive director.

It was while he was still on the job at Redwoods United that Berliner had his second musical epiphany, at the age of 50.

"On a vacation in Fort Bragg," he told the North Coast Journal for a brief news item last year, "I went into a store and there was a piece playing by Vaughn Williams, `Variations on a Theme by Thomas Tallis.' I thought about the ulceration problems of running a private not-for-profit agency.

"I looked at my wife and I said to her, `You know, this is what I'd like to do for the rest of my working life. I'd like to have a store like this where I can listen to music all day, I can read when there are no people and I can sell what I like.'"

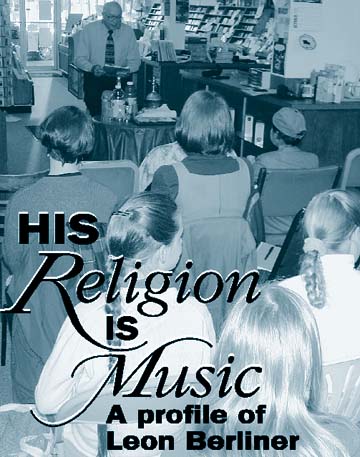

And that is what he has at Berliner's Cornucopia with the added attraction of a class in music appreciation he teaches every Tuesday night from early September to mid-June (to jive with Diana Berliner's school teaching schedule). [See headline photo at top]

"We've been doing it now for 15 years," he says, "and never advertised it. It's all by word of mouth. We've had as many as 34 and as few as three or four. If for two consecutive weeks four people don't show up, I'll end the class for that year. And that's happened just once."

On the nights I catch the class in October, there are 18 of us one night and more than 20 the next. Berliner, straddling or sitting in his huge throne-like chair, intersperses anecdotal notes about the composers on the agenda with excerpts from their music.

There is no charge, no "tuition" fee for the classes; in fact, Berliner provides the snacks for them cheese and crackers and an assortment of juice and wines. "But some people have said that it's the most expensive class they've ever taken, because they buy the discs. So it's not a problem," Berliner says. Then, with a grin, he tells me, "I even got you to buy!"

The classes are enlightening. I learn, among other things:

"The phenomenon of Lutheranism encouraged more music than any other religion," which is explained by Martin Luther himself having been a musician, who incorporated his own chorales into his services.

Georg Phillip Telemann, whom I must confess I was hearing for the first time, "wrote wonderful pieces and lots of them" including 1,043 church cantatas, and who was twice married and fathered 10 children, which made him "only half as prolific as Bach." (A photo shows Telemann, whose tenure was from 1681 to 1767, to have been a ruggedly handsome dude with a luxuriant dark beard and long hair -- a hippie long before his time.)

Our professor also tells us that Handel and Bach -- "these two great composers" -- never met, even though each had a chance at a good musical position if only they'd agree to marry "the fat and ugly woman" who came with the deal. Thanks, but no thanks, they said.

I get the feeling that there's a lot more interesting stuff relayed by Leon Berliner than you'd get in more formalized music appreciation courses.

But then Berliner is a man of many surprises. It is a Thursday morning when I walk into his Cornucopia to formally introduce myself (although I have gone in before as a customer, both for books and CD's), and he throws me by saying right off that it is his "holy Thursday" which is his weekly poker night. The game, he says, "has been going on for over 20 years," and there are about 12 active members.

"For a while," he adds, "it was a mental health game" meaning that most of the players when it started were "all people who worked in mental health," including several psychologists, a social worker and practically "the whole psych department of Humboldt State University." Decided me instantly that is was a game to avoid Never play poker with guys named Doc.

His other extracurricular activities include three days a week of racquetball, plus lending support to just about every musical activity in sight. He regularly appears on the KHSU fund drives to plug classical music, or will show up at HSU for such events as judging a concerto competition. Berliner himself plays guitar by ear although admitting that he hasn't picked it up lately.

Berliner and his guitar.

One of the big events of the year is coming up Dec. 16, Beethoven's birthday.

"The last day before Christmas season," he explains, "we're on Beethoven, and instead of holding the class here (at Cornucopia), we hold it at my house. And we do a potluck. And after eating, everybody sits by my speakers and our fireplace, and we listen to Beethoven's Ninth Symphony from beginning to end. Every year I've played a different performance of Beethoven's Ninth, for 15 years now. The reason I do that is because I've learned that less than 5 percent of American adults have ever sat through a Beethoven symphony from beginning to end."

Berliner notes, too, that he and son Larry on occasion will dance to Beethoven's Seventh Symphony. That music, Berliner says, "is what Wagner called the apotheosis of the dance." I had never heard it lauded as danceable, but I do remember James Agee advising, in "Let Us Now Praise Famous Men," to turn up Beethoven's Seventh as loud as you can get it, jam your ear as close to the speaker as possible, and you will find yourself as near as you will ever get to being inside the music. Agee quoted Beethoven as saying: "He who understands my music will never know unhappiness again."

Agee believed that, and I imagine that Leon Berliner would too.

He says at one point: "The best thing that ever happened to me was my wife, and the worst was the Holocaust."

Referring to the latter, he says: "There is not a day goes by that I don't think of what happened in those years."

One can't help wondering if his immersion in so many activities from reading and music to poker and racquetball might not be a way of helping to take his mind off those painful memories.

"An interesting question," he says. "I certainly don't do it for that reason. And if I went into deep psychoanalysis, who knows? Maybe that could be a conclusion. I do the things I do because they're fun, and I have never really focused on the possibility that (they) are a way of not thinking about the war."

He adds, "I don't protect myself..." although he didn't go to see Steven Spielberg's "Schindler's List" when it first came out (Berliner has in fact done a videotaped interview with a Spielberg representative on his recollections of the Holocaust), and he did have some initial qualms about going through the Holocaust Museum in Washington, D.C., on a visit there with his wife.

"We started up the stairs it's one of those circular museums and, sure, the tears welled up into my eyes immediately. But I didn't have to leave, because as I looked at other people, they all had tears in their eyes, too."

There was a time when he could have been characterized as an angry young man. "I was angriest as a teenager," he admits. In part, that was because he found himself when he first came to America "the cradle of capitalism" under suspicion because of his then-Marxist politics. (He has long since given them up "the god that failed.") Despite his education at CCNY in international relations, he was barred from a job in the State Department, for example, as a security risk.

He adds, "I was also angry at my fellow Jews who had not gone through the war at some of their attitudes, some of their ability to forget so easily or not to reflect on the horrors that had taken place."

Berliner says, "I have some very bitter memories. I think about anti-Semitism, the 12-year phenomenon in Germany. If there's a day that passes by when something doesn't come up that has to do with that event, I would be very surprised."

Obviously, as one observes when he's with his music, with his family, with his student friends in the Tuesday evening music appreciation classes, the youthful anger has dissipated somewhat. Oh, it's still there in a way, but more focused, and, as Berliner suggests, perhaps it is even more necessary today.

"If we're not going to repeat that part of history," he says, "then those who suffered directly from this horrible time in history must revitalize their memories if necessary, rekindle their anger so that we can communicate to generations to come in such a way that they don't repeat these horrors."

Choosing his words carefully, he concludes: "It's not an anger that I want to kill people. It's an anger that good men allow evil men to win out for such a lengthy period of time. So if you're going to be a good person, you have to speak up if you ever see evil again."

Comments? E-mail the Journal: ncjour@northcoast.com