|

by KEITH EASTHOUSE MIKE KELLY SAW IT COMING. BUT HE WASN'T THE ONLY ONE. In the weeks before the disaster, just about any federal scientist familiar with the Klamath River, not to mention experts with the Yurok tribe, recognized the danger: a larger than average run of Chinook salmon, fish stacked up in holes, warm water temperatures ideal for the spread of endemic diseases. The overriding thing on everyone's mind, the ominous thing, was proximity. Too many fish in too small a volume of water. "Yeah, we were talking about a fish kill," said Kelly, a fisheries biologist with the Arcata office of the National Marine Fisheries Service. "Everybody who knew the river was talking about how this is getting critical. Certainly everybody had it in the forefront of their minds." Not that it was super-obvious. The run of fall Chinook in the previous two years had, after all, been bigger. And there were other Septembers, although not many, when flows had been lower. It was more a feeling than anything else, albeit a feeling informed by expertise. As it turned out, there was something unique about September 2002: the flow releases from Iron Gate Dam, located more than halfway up the river, northeast of Yreka near the Oregon border, were the lowest on record when the numbers of returning fall Chinooks were at average or above average levels. But all anyone knew at the time, as summer gave way to fall, was that the water levels in the lower Klamath were very low indeed, and that a large number of fish, easily more than 100,000, were coming.

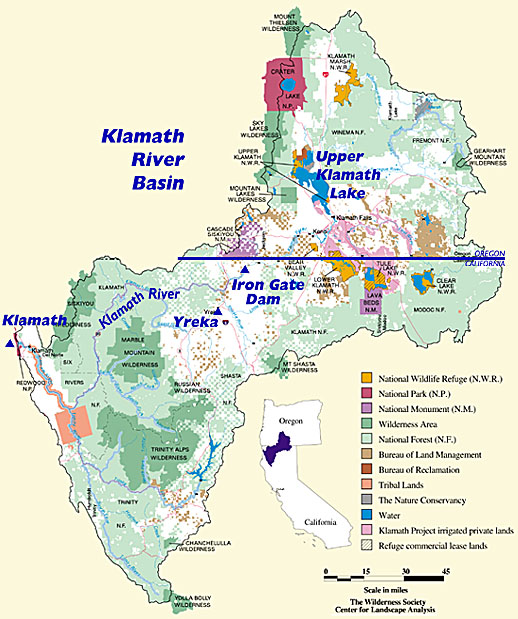

Last year was the first year of the plan, and while farmers in the upper basin received their full allocation, the river's flow below Iron Gate was slashed dramatically, to 750 cubic feet per second; that was two-thirds of its 2001 level and about half of the level recommended for any given September by the California Fish and Game Department. Not long afterward, around the middle of September, salmon began going belly up in the lower Klamath. By months end, a stinking, rotting mass, 33,000 fish in all, littered the river's last 36 miles. It was one of the largest fish kills ever recorded in the U.S., certainly the largest known on the Klamath. While 95 percent of the dead fish were chinooks, 30 to 40 were cohos, enough according to Kelly to be "significant." If Kelly's superiors had listened to him, the kill might never have happened. For while the danger of a fish kill may have been the subject of office chatter around the water cooler that summer, only Kelly had tried to do something that could have gotten the fish more water. Now, as Kelly rode the river on a jet boat with his colleagues, a river with carcasses "everywhere" -- on the banks, floating on the surface, carpeting the river bottom, even dangling as inadvertent catch from fishermen's' hooks -- he had a decision to make. What he had feared had come to pass, worse than he ever imagined. The question was what to do next. A plumbing system The Klamath River system drains nearly 10 million acres of mountains, high desert and farmland in southern Oregon and northern California. It was once the nation's third biggest producer of Pacific salmon, boasting all five species along with steelhead, green sturgeon and two species of mullet known as "suckers." Today, in addition to coho, both mullet species are so imperiled that they have federal protection, and the green sturgeon is also in trouble. The population of Chinooks and steelheads is down 90 percent from historical levels, and sockeye, pink and chum salmon have disappeared altogether. Kelly said that a few stray chums still enter the river on a fairly regular basis, quite literally the remnants of a vanished race. [See map of Klamath River Basin, bottom of story] The cause of the fishes demise is, few doubt, the reclamation bureau's Klamath Project, an elaborate network of dams, canals, lateral ditches and pumping stations that has thoroughly replumbed the basin. In addition to impacting aquatic life, it has transformed what was once a lush oasis -- the wetlands and shallow lakes that once dominated the upper basin have declined by 80 percent due to draining and filling. Presently, about 1,400 farming families depend on the irrigation system, which makes possible a $100 million agricultural industry. That may sound like a lot, but a 2002 study by the U.S. Geological Survey found that recreation -- boating, rafting, swimming, fishing and camping -- generated eight times as much money, and that if water were restored to the river, recreation would pump $3 billion a year into the regional economy. Additionally, the report said that buying out farmers -- offered by some as the only real solution for a basin in which there is not enough water to go around -- would cost $5 billion, but produce long-term benefits totaling $36 billion. News of the USGS report broke about a month after the fish kill. Given the timing, and the fact that there were allegations that the Bush administration had tried to suppress the report, a stir was created. That all went down at about the time news of another Klamath controversy broke. A scientist with the fisheries service, the man who was the "technical lead" for those biological opinions that had so rankled the reclamation bureau, was seeking protection under the federal whistleblower act, a law that shields federal employees who come forward with evidence of misconduct by their superiors. The whistleblower's name was Mike Kelly, and he was alleging that his own agency, despite being charged with protecting endangered species, had endorsed a plan that provided insufficient protection to the Klamath River's beleaguered coho population. So superheated was the Klamath controversy at that point that the news broke like a tidal wave. Kelly was besieged with interview requests from the likes of the Los Angeles Times and The News Hour with Jim Lehrer. He turned them all down. He hadn't come forward to bask in the limelight. He'd come forward, ultimately, to get the fish more water. Breaking the mold Kelly is an unusual sort of whistleblower. Often, they are employees in the latter stages of their careers who don't have much to lose by coming forward and accusing their bosses of misconduct. Kelly is only 38 and has a young family to support. Also, whistleblowers are typically loners and sticklers who are hard to get along with. Kelly comes across as affable and low-key; he's the opposite of shrill. He does share one trait with many whistleblowers, though. He has his standards. "He's definitely principled," said Eureka resident Rick Werner, a pilot and long-time friend. "He cares about the environment and he saw something [during the course of his work] that was wrong and he realized he couldn't live with himself if he went along with it." What Kelly thought was wrong requires a bit of explanation. During the course of a recent two-hour interview with the Journal, the first in-depth interview he has granted to a newspaper, he painstakingly laid out the events of last year from his point of view. He also talked about more current issues, such as how his whistleblower complaint played out this year; a federal judge's ruling this summer on a high-profile Klamath lawsuit filed by environmentalists, fishing groups and Rep. Mike Thompson, D-Napa; and what he foresees happening on the river in coming years. The heart of his whistleblower complaint, of course, was the fisheries service's weak-kneed performance vis-à-vis the reclamation bureau last April. The reality, though, was that the service was in a more difficult position than it had been in 2001, when it and another federal agency, the Fish and Wildlife Service, had issued "jeopardy" opinions, claiming that the Klamath project was posing an undue risk to coho. It was those opinions that forced the bureau to withhold water from farmers. By the spring of last year, things had changed. An "interim study" by the National Research Council, a branch of the National Academy of Sciences, had come out. It criticized the jeopardy opinions, arguing that there was no proof that higher water flows protect coho. The council's report was criticized by some scientists, not least because it had not made clear what would constitute an adequate level of proof. Nonetheless, the report gave reclamation leverage that it didn't have before. The "consultation," as negotiations between two federal agencies over endangered species issues are termed, was also different this time around. The 2001 jeopardy opinions had only pertained to Klamath Project operations that year; in 2002, the fisheries service was analyzing how the project might affect fish over the next 10 years -- a much more complicated task, obviously, and one that would of necessity require much more guesswork. It was that uncertainty that would end up working to reclamation's advantage. Caving In a four-hour deposition that Kelly gave in March as part of the lawsuit, he spelled out step-by-step how the fisheries service, faced with political pressure that, it now appears, originated in the White House, backed down on the issue that the entire flow schedule hinged on: the protection of coho salmon. At first the service came forward with an April 1 draft biological opinion that called for the bureau to increase flows in the Klamath River to create more habitat for coho. In a sign of the political pressure that was being brought to bear on the issue, the draft was reviewed by lawyers with the Justice Department, who according to Kelly dismissed it as "indefensible." More than two weeks later, on April 17, came another draft biological opinion. This one contained reduced spring flow recommendations, a concession aimed at mollifying farmers at the beginning of the 2002 irrigation season. It passed Justice Department muster and went to reclamation. During two days of meetings at the end of April, reclamation officials made clear that they could not operate the project under the flows recommended by the fisheries service -- a stance that had weight as the whole point to the consultation process is to protect endangered species and allow federal projects to move ahead. Stepping into territory normally reserved to the agency charged with enforcing the Endangered Species Act, reclamation proposed an alternative: They would provide 57 percent of the flows the biologists said the coho salmon needed -- but only after four years, by 2006. Until then, the fish would have to make due. They agreed to meet the fisheries service's flow recommendations -- but not until 2012, 10 years down the road. What of the 43 percent that reclamation said it would not be responsible for? That was poorly defined at the meeting. Bureau officials expressed hope that California and Oregon would give up some of the water they claim from the basin, neither then nor now a likely development. They also talked about creating a water bank by buying water from unspecified sources and storing it in Upper Klamath Lake to be used when needed. While the bureau said 57 percent represented the amount of water they draw from the basin, to Kelly it appeared to be an arbitrary amount; at the least, it was an amount that had "nothing to do with what would be needed to avoid jeopardy." Kelly thought it was a very bad deal for the fish, particularly since under the bureau's plan coho would not receive enough water to ensure their survival until the ninth year of the 10-year plan. But non-scientific considerations were clearly at play. On the morning of the second day of meetings, John Lecky, Kelly's superior, received a call from an official in the Commerce Department, which has authority over the fisheries service, and was told that he and his scientists were "stonewalling." When Kelly, Lecky and another official with the fisheries service walked into the meeting later that day, Lecky and a reclamation official quickly left the room and didn't return for 45 minutes. When they got back, Lecky announced that the fisheries service would accept the 57 percent plan as long as it was approved by the agency's own lawyers. Within a week, it was. Not long afterward, Kelly asked to be "recused" from his position as technical lead of the biological evaluation of the Klamath project. The straw that broke the camel's back was Lecky's refusal to allow Kelly, or anyone in the fisheries service, to evaluate the potential impacts to coho under reclamation's plan. It was that lack of analysis that Kelly cited in his whistleblower complaint as a clear violation of the Endangered Species Act. Setbacks This spring the complaint came before the Office of Special Counsel, which is required by federal law to investigate whistleblower claims. To the dismay of Kelly and the group representing him, Public Employees for Environmental Responsibility, a Washington, D.C.-based nonprofit, his complaint "never passed the first threshold," as PEER executive director Jeff Ruch put it in a telephone interview this week. In a March 5 letter, Associate Special Counsel Leonard Dribinsky said that it was unclear that there had been "a substantial likelihood" that the fisheries service had violated the act, and that he also couldn't conclude that the service had been responsible, in whole or in part, for the fish kill. Noting that a federal district court was hearing a related lawsuit, Dribinsky closed the case. Essentially, it never got a hearing. "We were astounded," recalled Ruch, who said the OSC process does not allow for appeals. What did Kelly's complaint in, according to Ruch, was the research council's "interim study" that criticized the 2001 jeopardy opinions. "Because [that report] challenged the level of the science that the agency then had, [Dribinsky] determined that the agency had reasonable leeway to reach different conclusions. "That may or may not have been true," Ruch added. "But that didn't allow them to throw a dart and pick a [flow] level." A ruling in July by federal district judge Saundra Brown Armstrong proved to be more of a mixed bag. She declared the final biological opinion that the fisheries service came up with, the one Kelly had objected to, was invalid -- but not for the reasons Kelly had cited. Instead, she said that the fisheries service had failed to make clear what level of negative impact to the coho it would tolerate. Without that information, which would trigger a new round of consultation with reclamation, the opinion was not in accord with the Endangered Species Act, the judge ruled. The judge also directed that the fisheries service include in a revised biological opinion more specific information about where the 43 percent of the water that reclamation says its not responsible for is going to come from. Kelly, for his part, said he wished the judge had addressed another issue: The need to err on the side of caution in protecting endangered species, which he said is called for under the Endangered Species Act. Hope That, in essence, is where things stand now, although more Klamath reports have recently come out. One, from the Fish and Wildlife Service, echoes an earlier study by the state Fish and Game Department that said low flows likely played an important role in the fish kill. A final version of the national research council report has also been released; it calls for a variety of measures, not simply restoring flows, to revitalize the Klamath. Meantime, as if to complicate matters further, everyone is awaiting yet another study, one that could quantify the water rights of the Yurok and Karuk tribes. Since the tribes have senior water rights, the results of this study could conceivably result in what Kelly and tribal biologists have been arguing for all along -- more water in the river. Finally, Kristen Boyles, a lawyer with Earthjustice, which represented fishing and environmental interests in the lawsuit, said the firm is appealing Judge Brown's ruling to the Ninth U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals, a judicial body known for its pro-environment rulings. In particular, Boyles said, Earthjustice will contend that the fisheries service violated the law by giving the reclamation bureau several years to provide an amount of water that it said coho needed now for its survival. Again, not quite what Kelly was contending, but close. As for Kelly, he's busy on other projects at the fisheries service, including one that's pretty high profile: the restoration of the Trinity River. But he's been shut out of anything having to do with the Klamath, which he said was "understandable." "I'd just keep pointing to the flows and they don't want to hear that," Kelly said the other day. When asked about the likelihood of more fish kills on the Klamath, he said that if the status quo remains unchanged, it's a real possibility, particularly in dry years. Interestingly, the whole experience has created common ground for Kelly and his dad, Dale Kelly. Like his son, the elder Kelly is a scientist, an engineer to be precise, who has found himself smack dab in the middle of a political fight: the battle to convert to digital television. Dale Kelly, it turns out, is a strong advocate for small radio and TV stations who want to go digital but don't want to be swallowed up by media giants in the process. He's serving on an advisory committee to the Federal Communications Commission, and, according to his son, has taken his share of heat from attorneys representing corporate media. He has evidently learned a sobering lesson: "It doesn't matter how rational an explanation you can offer in technical terms," Kelly said his dad told him recently. "If the political will is contrary, what you say won't be heard." Obviously, Kelly can relate to that. But he said the two have nonetheless managed to avoid getting bitter. Kelly, for example, had this to say when asked if he had any regrets: "I'd do it all over again." IN THE NEWS | GARDEN | EDITORIAL | GOOD NEWS | CALENDAR

Comments? © Copyright 2003, North Coast Journal, Inc. |

![[dead fish in river]](cover1113-deadfish.jpg) The

situation was on everybody's radar screen for another reason:

the federal agency Kelly works for, the fisheries service, had

had, the previous spring, a confrontation of sorts with the federal

Bureau of Reclamation. In the drought year of 2001 the fisheries

service had forced the bureau to leave water in the river for

coho salmon, a federal "threatened" species. Irrigators

in the upper basin cried foul -- and made headlines across the

country as they formed "bucket brigades" and stormed

canal head gates. Not surprisingly, the following year, last

year, the fisheries service was under tremendous pressure to

back off. In April, the agency put forth two versions of a "biological

opinion" that evaluated the impact of the nearly century-old

Klamath irrigation project -- both were greeted with vehement

objections by federal officials for being too heavily weighted

toward protecting coho. At the end of that month, following two

days of face-to-face meetings, the fisheries service signed off

on a 10-year "flow schedule" for the Klamath that,

in effect, put farmers back where they were used to being --

first in line for water -- and put everybody else behind them

-- Indian tribes, the commercial and recreational fishing industry,

fish.

The

situation was on everybody's radar screen for another reason:

the federal agency Kelly works for, the fisheries service, had

had, the previous spring, a confrontation of sorts with the federal

Bureau of Reclamation. In the drought year of 2001 the fisheries

service had forced the bureau to leave water in the river for

coho salmon, a federal "threatened" species. Irrigators

in the upper basin cried foul -- and made headlines across the

country as they formed "bucket brigades" and stormed

canal head gates. Not surprisingly, the following year, last

year, the fisheries service was under tremendous pressure to

back off. In April, the agency put forth two versions of a "biological

opinion" that evaluated the impact of the nearly century-old

Klamath irrigation project -- both were greeted with vehement

objections by federal officials for being too heavily weighted

toward protecting coho. At the end of that month, following two

days of face-to-face meetings, the fisheries service signed off

on a 10-year "flow schedule" for the Klamath that,

in effect, put farmers back where they were used to being --

first in line for water -- and put everybody else behind them

-- Indian tribes, the commercial and recreational fishing industry,

fish.