|

State Inspections show pattern of dangerous short-staffing at SunBridge. The financial reports show a company on the ropes.by ARNO HOLSCHUH

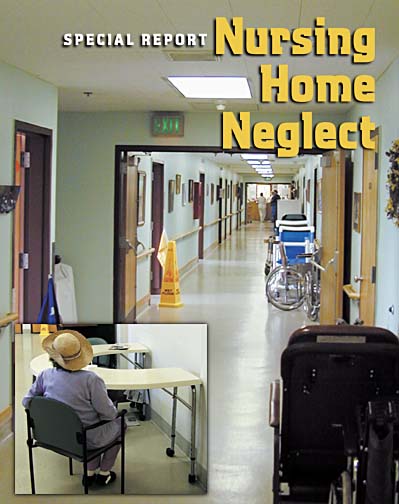

One staff member later told state investigators she had seen him with his hand on the facility's gate latch four times over a period of seven months. "Out the door was a big problem for him," she said. Another staff member said Resident A escaped "all the time," as often as four times a shift and had even written a letter of concern to the facility's administrator. There was only one nursing assistant on duty in the wing of the nursing home April 22 at 3:30 p.m. when Resident A opened an exit door, rolled his wheelchair out, unlatched a gate and fell down 12 concrete steps. An off-duty staff member, who voluntarily stayed behind to ease the staff shortage, heard the sensor go off and rushed to help. She arrived just in time to witness the fall. Resident A, unconscious and bleeding from the head, was hospitalized with fractures of the skull and spine. He died a week later. State Department of Health Services investigators later determined that SunBridge Granada was operating "below target staffing levels" when the incident occurred. The facility had broken a federal law by failing to provide adequate supervision and assistive devices to prevent such accidents. Granada received an AA citation -- the most severe sanction under state law -- and a $25,000 fine. Sun Healthcare Group Inc., the parent corporation of SunBridge, is appealing the citation. But state reports show that Resident A is just one example of the widespread problems for the SunBridge group, which owns all four Eureka nursing homes. (The only other nursing home of comparable size in Humboldt County is St. Luke's in Fortuna, not affiliated with the SunBridge group.) SunBridge facilities are not uniform in the kind and quality of care they provide, but all have received more than the average number of warnings from state regulators over the past four years. ![[photos of SunBridge nursing homes]](cover1109-nursehomes.jpg)

Cynthia Ross, a long-term-care ombudsman for the Area Agency on Aging, works with North Coast nursing home residents to protect their rights. "The bottom line is that you need enough [staff] to give sufficient care," Ross said. "I would say proper staffing is the key, by which I mean nurses and nurse assistants." She declined to point fingers at any particular nursing home but said that during her tenure she had seen "residents who are suffering because the quality of care had suffered because staff was absent." One staff member who works in a Eureka SunBridge facility told the Journal that the persistent staffing shortages at her facility were well-known. (She declined to give her name for publication for fear of losing her job.) "Sometimes there will be one person on a shift and we'll have to pull people from other facilities to even work the floor. There are supposed to be six aides on the shift, and sometimes we have three or four. We have a lot of people falling and stuff when it gets really bad," she said. Residents that require assistance with eating often do not receive it, vital signs are frequently not taken when they should be, and some residents have to wait as long as two weeks between showers. She said that it wasn't the staff's fault. "We all feel like we do an impossible job. They ask us to do impossible things and we do the best we can." Sixteen-hour days were "not unusual" and there are often 20 or 22 residents per nurse assistant when "eight to 10 would be reasonable," she said. Her description of the facility as a workplace is simple: "Hell. Welcome to hell."

SunBridge Granada Care and Rehabilitation, 2885 Harris St., is advertised on the Internet as offering "more than high quality medical and rehabilitative services. Our personalized care sets us apart." But the results of the facility's annual inspection by the state Department of Health Services, called a "survey," should give current and prospective patients -- and their families -- cause for concern. Some deficiencies are minor, like not allowing residents access to their petty cash accounts on weekends or not posting a list of residents' rights in large print. The most serious failures stem from staffing shortages. During one inspection a 79-year-old man, disabled by a stroke, was found sitting up in bed and trying to eat his dinner. His right hand, which held his spoon, was shaking so badly that little food made it to his mouth. His milk had already spilled onto his chest. He was unable to use the call button due to coordination problems and was calling softly for help that did not come even though he had been classified by Granada's staff as "needing help with all activities of daily living." After an hour, a staff member arrived and collected his tray. The inspector who witnessed the event estimated the man had been able to eat only about a quarter of his meal. A 94-year old woman was found by state regulators during their last inspection "in a urine-soaked gown and bed with a brown ring of dried urine on her sheet and pad, extending from knees to mid-back." A staff member was feeding her when the inspectors came by her room. When asked why something had not been done about her situation, the staff person replied that she knew the woman was wet but did not have time to change her pad. "Day shift is supposed to do rounds before they leave," the staffer said. "We roll them up in bed and put bibs on them for dinner. That's all we have time for. There are two aides tonight for 43 people on this hall." The survey lists several similar incidents, especially concerning failure to change incontinent residents for extended periods. Again, both residents and state inspectors trace the problems to a lack of staffing. During a group interview with Granada residents, inspectors found that "10 of 11 alert and oriented residents who attended the group interview stated that there is not enough staff in the facility to care for their needs on a consistent basis." Eight of 11 said they had missed showers because there weren't enough staff. Ten of 11 said they had waited more than 10 minutes for their call lights to be answered. One resident said he had an attack of diarrhea one night and was unable to raise a staff member for more than 50 minutes. He said that when a nurse's aide finally came, she told him she was the only aide in the facility at that time.

For all of its problems, Granada may be not be the most troubled of SunBridge's Eureka facilities. SunBridge Seaview, located just south of Eureka at 8400 Purdue Drive, has a history of violations of quality standards. In 1998 the survey turned up 128 deficiencies, more than seven times the state average for nursing homes. The problems run from employing nurse aides without checking their references and failure to prevent or deal with physical fights between residents, to more serious claims of medical conditions such as untreated bed sores. Inspectors found that residents did not have adequate access to drinking water, were not given blankets when they asked for them and did not have hot running water. The biggest problem, again, was staffing. "Interview with licensed staff member reveals that she does not think there is enough staff to adequately supervise all residents," reads one passage of the state survey, which is available for public inspection in each facility. The inspectors' review of staff records revealed that during the two-week period prior to the inspection, there were sometimes six staff members short. Seaview's chronic problems have earned it a listing on the Department of Health Service's Focused Enforcement List, which is a pilot project designed to concentrate enforcement efforts on the facilities with the worst records of compliance with state and federal laws, said Lea Brookes, public relations officer for the department in Santa Rosa, in a telephone interview. Seaview is one of only two care facilities on the list for all of Northern California. There are just 34 of the 1,400 facilities in the state on the list.

SunBridge Care and Rehabilitation for Eureka, 2353 23rd St., has had problems as well. Several residents told state investigators that the facility was short-staffed. Some residents still able to control their bodily functions but requiring help getting to the bathroom became effectively incontinent. Other patients resorted to transferring themselves into wheelchairs, risking broken bones rather than soiling their sheets. Of particular concern at Care and Rehabilitation, inspectors found, was overmedication. One report concerned a resident who, when admitted July 1998, was in full possession of her faculties. Records show she was social and amiable and enjoyed spending time with her husband, also a resident. But when her husband died in February 1999, her mental condition began to deteriorate. Without consulting a psychiatrist or psychologist, the woman's physician began administering psychotropic medications. At the time of the inspection, she was on six different medications, had lost 23 pounds and was considered a difficult resident by staff members. The survey criticizes the facility for overmedication, not safeguarding against possible drug interactions and understaffing. There was no psychiatrist or psychologist performing evaluations on potentially mentally ill residents. The facility submitted a "plan of correction" to the state, but administrator Margot Julian declined to comment on whether there is now psychiatric evaluation available. (The SunBridge corporate office in Albuquerque, N.M., asked that all communication for this report be conducted with someone there.)

SunBridge's fourth Eureka skilled nursing facility, SunBridge Pacific, fared better in state surveys. AAA Ombudsman Cynthia Ross said Pacific, at 2211 Harrison Ave., has put forth a significant effort to improve the lives of its residents in recent years. While she has seen problems in some homes, she said, "I have also seen the opposite, where there was excellent care and excellent quality of life." She cited Pacific's "Eden Alternative" program, which tries to create a home-like atmosphere by allowing residents to keep pets and to use non-institutional furniture. But Pacific is the exception to SunBridge rule. Administrator Maxine Roby said that Pacific was the only facility in Eureka that has been able to hire enough staff to fill its roster. And Roby said she has held her position longer than any other SunBridge administrator in Eureka -- three years -- allowing her to implement a philosophy of care. The other facilities have had a high turnover of administrators. One former SunBridge Eureka administrator, who spoke only on condition of anonymity, said he left after a little more than a year because he didn't agree with how the company was being run. "The problem that I see is that Sun as a corporation did not serve this community well because they did not provide any support to people actually doing the work." He cited low wages for direct-care staff and a consequent inability to fill vacancies. He confirmed that there are staff shortages at local SunBridge facilities, and that it is not unusual for existing to staff to work 16-hour days. "I always believe you can provide excellent care in a cost-effective manner and, in my opinion, the corporation got greedy."

But financial statements show the opposite of greedy profit-taking. Sun Healthcare Group Inc. declared bankruptcy Oct. 14, 1999. The price of a share of Sun stock had fallen from a high of $20.13 in the first quarter of 1998 to a low of just 7 cents in the last quarter of 1999. In 1997 the company's net earnings were about $34 million. In 1999, its net loss was more than $1 billion. Given that fiscal situation, it isn't surprising that Sun is short-staffing its facilities, said Prescott Cole, a San Francisco attorney with the organization California Advocates for Nursing Home Reform, in a telephone interview. "Nursing homes, as businesses, have fixed incomes and fixed expenses. The real variables are staffing and food." Cole said he has seen cases where the parent corporation will actually give bonuses to management if they can figure out ways to keep staff levels low. "(Short) staffing has always been the way to make money," he said. "And this industry isn't mostly about money. It's all about money." Sun Healthcare is one of a number of casualties of legislation that changed the way the government pays for health care, Cole added. Prior to 1999 nursing homes would arrange services for residents like respiratory or physical therapy -- called ancillary services -- through separate vending companies. They were reimbursed through Medicare for the cost of the treatment. "So the industry got the idea to start their own vending companies. They'd provide services to themselves and bill the government." The result was inflated bills for ancillary services.

During that period when nursing homes companies were profitable, Sun Healthcare was born. It acquired its first facility in 1996 and by the beginning of 1999 it was operating more than 90 nursing homes, making it the largest provider of skilled nursing care in California and a very large debtor. "There was a very `cush' time, money was rolling in and facilities were in a big buying mode," Cole said. But that ended soon. Cole said in the constant search for ways to tighten the budget, Congress looked to Medicare, found waste and decided to change the payment system to one that would be harder to abuse. "So the government at some point says, `Wait. We'll look at how sick people are, and then pay for what they see.'" That moment came on Jan. 1, 1999, when the federal Balanced Budget Act went into effect. The law stipulates that Medicare pay for nursing home care according to fee schedules and that they pay no more than $1,500 per patient per year to any one provider of ancillary care. "So the floor fell out" for nursing home companies, said Cole -- Sun included. Sun's annual financial report to the Securities and Exchange Commission states that "prior to the implementation [of the Balanced Budget Act], Sun's ancillary services ... had significantly higher operating margins than the margins associated with Sun's long-term and subacute care facilities and accordingly such facilities provided most of Sun's operating profits." The act's Medicare provisions, says the report, "significantly affected" the company's financial health, reducing its Medicare revenues by more than half. A company flush with capital may have been able to take such a blow, Cole said. But because Sun has lots of debt to service, the money ran out. It was a little more than 10 months after the Medicare change that Sun declared bankruptcy. Greg Johnston, a spokesperson for Sun, said drawing any connection between bankruptcy and patient care is absurd. "There is not any significant cost cutting, and patient care is not jeopardized in any way," he said. The company was responding to bankruptcy by "divesting itself of facilities," he said, although the company does not plan on selling off any Eureka facilities. While he did not admit to staff shortages at any SunBridge facility, he pointed out that there is a national shortage of nursing home staff.

"Everybody's having trouble finding nurse assistants," said Linda Wahlbaker, administrator at St. Luke Manor, a Lutheran nursing home in Fortuna. Wahlbaker said there is more than one way to respond to a staffing shortage. When the facility saw that it wasn't able to fill its staff rolls, it could have increased working hours for the staff or tried to scrape by with fewer direct care personnel -- the SunBridge solution. Instead, St. Luke started to reduce the number of residents. The ratio of residents per staff member has stayed at about 8:1, she said. That's hurt the facility's finances, because it is required to pay upkeep on the building and other overhead at the same rate even if the number of paying "customers" diminishes. Wahlbaker said St. Luke loses about $30,000 a month. But, she said, profit "has never been our mission ... and I can honestly say we've never turned a profit." The deficit is made up through fund-raising efforts. Wahlbaker said it is community involvement that allows St. Luke to provide excellent care -- as reflected in a survey where serious concerns like untreated bedsores, failure to care for incontinence and falls are conspicuous in their absence. And rather than take a defensive attitude toward the few failures which are noted in the survey, Wahlbaker said the facility tries to see them as helping to assure quality. "My philosophy has always been that regulations are there for a reason and we need to work with the regulating agency to provide good care." After all, Wahlbaker said, "Regulations are meant to protect people -- and our mission is to care for people and their needs." IN THE NEWS | ARTS! ARCATA | EDITORIAL | CALENDAR Comments? E-mail the Journal: [email protected] © Copyright 2000, North Coast Journal, Inc. |