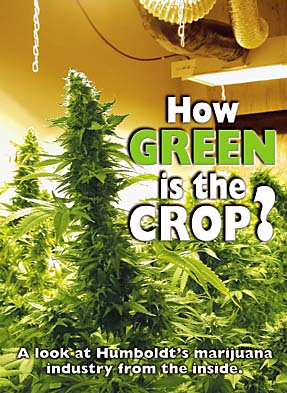

|

Story and photos by BOB DORAN

R. G LIVES NEXT DOOR -- or down

the street -- in a modest home that could probably use a coat

of paint. He drives a 9-year-old car. His kids may play soccer

with your kids and he sometimes watches football on Sunday. But

there's a big difference between you and this neighbor. Mr. G

makes more than $100,000 a year in a criminal enterprise. He

grows marijuana.

Of course he has another name.

We chose "G" for green, the color of the product he

turns out, and "G" for grower.

And he's not the grower you

may be used to reading about. For decades sinsemilla marijuana

has been a cash crop for many of those living in Humboldt County's

hills. Every summer and fall police helicopters crisscross the

hidden valleys searching for patches of green. (See separate

story.)

Mr. G is the one you read about

in police reports when he is busted for growing marijuana in

a spare bedroom in downtown Eureka, Arcata, Fortuna and other

urban and suburban neighborhoods near you.

![[inside grow room]](cover1108-growroom.jpg) "There are many, many small indoor

operations throughout Humboldt County," said Mark Harris,

an Arcata attorney who specializes in marijuana defense. "It

is much more pervasive than people realize -- at least people

who don't grow or use marijuana. It could be the butcher, the

baker, the candlestick maker. These are people from all walks

of life. At every level from blue collar to professional, people

can have 10 or 20 plants in a closet under a couple of lights." "There are many, many small indoor

operations throughout Humboldt County," said Mark Harris,

an Arcata attorney who specializes in marijuana defense. "It

is much more pervasive than people realize -- at least people

who don't grow or use marijuana. It could be the butcher, the

baker, the candlestick maker. These are people from all walks

of life. At every level from blue collar to professional, people

can have 10 or 20 plants in a closet under a couple of lights."

Walking in the front door of

Mr. G's house you are struck by the smell -- not the smell of

marijuana, the smell of bacon. He has just cooked breakfast for

his clipping crew. As they return to work he gathers the dishes

and leaves them to soak in the sink while we sit down to talk

about business.

G has been a pot smoker since

he was a teenager. Over the years he dabbled in outdoor growing

and small scale sales.

"At one job site I was

working on I had access to neighboring woods," he said.

"My work kept me returning to the area, so I would go after

work, before work or during lunch hour, and tend to a small garden.

It never amounted to much, just a few thousand dollars. It was

a nice payoff at the end of the year for very little work. But

what I'm doing now is on a different level."

Mr. G said his business is part

of a local trend in part brought about by CAMP -- the Campaign

Against Marijuana Planting.

"There are obviously still

plenty of outdoor growers, but you can't grow in the full sun

any more and that's what produces the really good buds. It's

rare to get outdoor [marijuana] today that has been grown in

full sun. People have to grow under the trees to avoid detection

from the air," he said. "And the outdoor grows have

become more labor-intensive. People used to use backhoes to plant

football field-size pot patches. That's definitely not happening.

The outdoor grows have generally gotten smaller."

Humboldt County Sheriff Dennis

Lewis said his officers do a pretty good job on interdiction

when it comes to outdoor marijuana grows. He said he believes

the annual raids remove a large share of what is grown outdoors

from circulation. But it's a different story when it comes to

the expanding number of indoor operations.

"When you factor in the

indoor grows, I don't think we do get the majority," he

said.

"These indoor operations

have been increasing for a number of years," said a Fortuna

police officer who handles controlled substances investigations

for the city. "It's a profit-motivated business. They can

do it year 'round. Here in Fortuna we're seeing larger operations

and at least a few people who have moved here from out of the

area to do this. People are moving here because it's widely publicized

that Humboldt is the mecca of marijuana."

![[photo of plant]](cover1108-bud.jpg) How do the police discover indoor grows? How do the police discover indoor grows?

"A lot of times we hear

from citizens who are concerned about what's going on in their

neighborhood," said the Fortuna officer, who wanted to remain

unnamed for this report. "People who find something out

whether they stumble across it, or someone doing it is bragging

about it."

Sheriff Lewis said, "We

have our eyes, we have our ears, we have our noses. Sometimes

we find marijuana by accident."

You might think that a marijuana

factory in a spare bedroom would be an easy thing to detect because

of its pungent odor. That was one of G's primary concerns when

he set up his indoor operation.

"The first thing you do

is you go in there and deal with ventilation," he said.

"You build a system that draws fresh air in and hot air

out. It's ideal to have some sort of filter so the smell of flowering

marijuana doesn't fill up the whole neighborhood." Once

the ventilation is in place, "It's just gardening."

"I do it just like you

would outside, except I have an artificial sun. You hang a few

lights, then you decide whether you're going to go hydroponic

or with soil. In my case I use soil. It seems to be more forgiving.

I can water the plants and walk away. I don't have to worry about

the ph balance being just right.

"Sometimes you need to

look at the wiring in your house. A lot of times with operations

like this, people will catch their house on fire because they

try to put too many appliances on inadequate wiring. I had an

electrician come in and hook up a separate dedicated circuit

for the room."

His electric bill is high --

each of his six grow-lights draws a kilowatt per hour -- but

he doesn't really worry about PG&E turning him in.

"If you're paying for your

power that's all they care about. I've talked to many people

who have three- to six-light [growing operations] in their places

-- and we're talking scores of people -- and it never comes up,"

he said. "You pay your bill. It might be $500 to $800 a

month for electricity.

"I've talked to lawyers

and have never heard of a case coming to trial based on PG&E

reporting someone for using too much power."

According to PG&E spokesman

Lloyd Coker, called at his Santa Rosa office, customer billing

data is privileged information.

"If the cops call me tonight

and say `I need you to tell me if so-and-so's bill is a lot higher;

we suspect he may be growing marijuana,' we say, `I'm sorry,

we can't give you that information, because all those customer

accounts are confidential,'" Coker said. "If it's a

criminal investigation, they can subpoena the PG&E information

and I imagine there's a way we will cooperate. I just don't know

to what degree because of the confidentiality that is inherent

in customer accounts."

![[photo of clones]](cover1108-clones.jpg) Sheriff Lewis said often times a grower

using a commercial power source may bypass the meter so the utility

doesn't know. But does PG&E automatically inform law enforcement

when they catch someone stealing power? Sheriff Lewis said often times a grower

using a commercial power source may bypass the meter so the utility

doesn't know. But does PG&E automatically inform law enforcement

when they catch someone stealing power?

"Absolutely not,"

said Coker. "We want to be certain without a doubt that

there is diversion of electricity going on. We enlist the help

of the local police agency if we need to [but] often a simple

letter will suffice: `Hey, we noticed some discrepancies here,'

and often that will straighten things out. We'll send them a

back bill, it gets paid, nobody says anything, everyone goes

away happy."

Mr. G said it's true that some

growers steal power, but it's not only unnecessary, it's unwise.

"It's a felony -- grand larceny. And it's actually an added

enhancement [additional charges] if you ever get busted."

Of course, getting busted is

a concern for Mr. G but he doesn't seem overly worried about

it. "The scale we're talking about here, it's practically

legal. People who get busted for having a few lights rarely do

any prison time. They get probation or drug diversion, especially

if it's their first offense.

"Since I have never been

arrested, I look at it like this: I have one free try. If I get

popped I have to stop because I'm not going to risk my freedom.

But the way the law is now, if you can afford to hire a lawyer,

the first offense is just a slap on the wrist. You get to walk

away and pick up your life."

He doesn't take the possibility

of discovery lightly. One concern is drawing the attention of

the IRS. He avoids conspicuous purchases. He doesn't drive a

brand new car or truck, even though he can afford one. And he

still works, in part as a way to explain the money he makes.

"One thing I do is deposit

a certain amount in the bank every month and declare it as earnings,"

he said. "I do the estimated tax thing and pay taxes on

what I deposit. I suppose if I was audited it might go bad against

me but again I try to keep a low profile."

Another precaution is a reduction

in the number of plants he grows.

"There are two schools

of thought on plant numbers. One is called `sea of green.' You

basically fill your area with as many plants as you can. I used

to have 300 growing very close together under six lights. I would

only grow them 8 inches high before I would induce them to flower.

After experimenting, I reduced the number to less than 100.

![[pots of young plants]](cover1108-potsofpot.jpg) "I don't have any concrete

evidence about it, but the rumor is the feds are less likely

to prosecute you if you have under 100 plants. If you get busted

for this, you don't want to be federally prosecuted. Federal

sentencing guidelines are more stringent. They throw the book

at you." "I don't have any concrete

evidence about it, but the rumor is the feds are less likely

to prosecute you if you have under 100 plants. If you get busted

for this, you don't want to be federally prosecuted. Federal

sentencing guidelines are more stringent. They throw the book

at you."

One hundred plants might seem

like a lot, but according to attorney Harris, even 300 could

be considered small potatoes.

"The DEA's position has

been that if it is under 1,000 plants, they're not interested,"

Harris said. "That comes with a caveat: There can be other

reasons the feds will become interested. If weapons or other

types of drugs were involved, or a high level of sophistication."

Lewis agreed. "Prior to

being elected sheriff, I was a DA investigator for many years,

and one of my assignments there was narcotics," he said.

"At one point, the federal

prosecutor's standard was exactly what [Mr. G] said -- 100 plants.

If there were fewer than 100 plants, they would decline,"

he said. "[Today] that is well below what they would normally

prosecute. That's not to say they can not or will not prosecute.

But as a general rule, they're not interested in grows smaller

than 1,000 plants."

Even if the federal authorities

are not interested, cultivation and possession of marijuana for

sale is still a felony. And Harris points out, "A felony

is never a slap on the wrist. There are times when a sentence

may not include jail time, but it may include a large amount

of community service or some work-alternative program. I think

the fear for most people is the felon status."

Mr. G said he is aware of the

risks. "I've seen people go down. I've seen what happens.

They go to jail for a couple of days. They make bail. They go

to court a bunch of times and it's resolved, usually with drug

diversion or a suspended sentence or sometimes an actual sentence

of a year or two. I'm not saying there's no risk. There's a certain

dread that I have to live with. But I'm willing to take the risk

for the rewards."

And in a show of entrepreneurial

spirit, Mr. G is making it possible for his friends to also reap

those rewards, even if they don't have the capital for a grow-room

startup.

"It takes an investment

of $3,000 to $4,000 for the equipment and other things you need

to start a small operation," he said. "I offer a deal.

I set them up with a grow room and I get half the profits for

a year, then it's theirs. Over the year I teach them how to do

it and do part of the work. Once they have it down, all I have

to do is stop by and collect my cut."

Mr. G says the number of people

getting involved in the business is increasing. "I think

there are a tons of people doing it. Of course, I have the point

of view of a grower, so I assume if I'm doing it and it's this

easy, everybody must be doing it." But he said there is

other evidence of indoor growing's popularity.

"You see the stores in

every town [stores that offer nothing but growing supplies],

not to mention the fact that all the nurseries have an area for

products designed specifically for pot cultivation," Mr.

G said. "You don't use bat guano on your tomatoes. Maybe

some people do, but it's expensive. If you ask for bat guano

you get a wink. They know what you're using it for."

"I don't see that the law

enforcement effort does anything to diminish that temptation

for folks [to grow pot]," said Harris. "I think if

anything [CAMP] tends to drive the price up, making the temptation

greater."

The officer in Fortuna said

he has observed indoor operations getting larger and slicker.

"People who have done it

for awhile are getting more sophisticated and when that happens,

they are able to move the size up a bit. And hey, the economy's

not very good right now either and people need to supplement

their incomes. I expect to see even more in the coming years."

Clones, clippers & cash: An interview with

Mr. G

The Journal: How much finished

product does a grow produce?

Mr. G: The industry standard

is a pound per 1,000 watts of light in about 10 weeks. If you

have a fresh batch of clones ready to go when you harvest, you

can conceivably get a harvest every eight weeks.

![[photo of clipper]](cover1108-clipper.jpg) Where do these clones come from? Where do these clones come from?

Some people are in the business

of selling clones. That's all they do. They'll grow a few nice-sized

plants and take cuttings off of them. They put them in little

trays and they take root. It's just like any houseplant. You

can buy them for between $5 and $12 a clone on average. Some

people ask $20 for one clone, usually because it's a good strain.

What is "a good strain"?

Just like with vegetables or

dogs, you breed for specific things. The trade-off is that the

super potent quality pot generally produces less quantity. High

yield strains don't have the same quality. You look for a balance.

Some of the popular ones are Northern Lights. It's been around

for a long time. There's one called Big Bud, Skunk No. 1 and

No. 2, Snow and White Widow. Those are all ones you can get from

Amsterdam seed banks.

Pot is legal in Holland so people

grow the seeds and deliver them to the bank and they mail them

out. The postal service confiscates some, but a lot go through.

I tried different varieties.

The one I'm happiest with is Northern Lights, bred specifically

for indoor growing.

Is there some advantage to

growing outdoors?

![[photo of buds on drying rack]](cover1108-dryingrack.jpg) Sure. An important one is

you can grow on federal land instead of on your own property.

When you're growing in your bedroom it's pretty hard to deny

that you knew the plants were there. Sure. An important one is

you can grow on federal land instead of on your own property.

When you're growing in your bedroom it's pretty hard to deny

that you knew the plants were there.

And there are certain qualitative

differences in the buds. Some prefer the flavor of outdoor. It

looks a little different. It's gnarlier, it's thicker and more

robust-looking than indoor. There's definitely a market for it.

When harvest season comes around people are clamoring for it

and, in fact, indoor product becomes harder to sell. But after

the harvest flush is over and people have smoked up all the outdoor,

they come back around to indoor.

How do think your business

fits in with the local economy?

I buy growing supplies at local

stores and of course I spend other money locally. And I'm also

an employer. I hire people to do the processing. Manicuring is

quite labor intensive so I hire that out. There's a community

of people who are known as good clippers. Some support themselves

entirely by going from one operation to another. With all the

indoor operations there's work year 'round.

It's generally piece rate at

$200 a pound and on average you can do an ounce per hour. That

works out to about $12.50 an hour cash. It used to be lower but

it has come up. With the clippers working for many different

people they can set the price to some extent.

Are you involved on the retail

side?

Not at all. It's unwise for

a grower to be a dealer. I have a buyer who comes by every couple

of months and takes all I've got. You don't want to be known

as a pot guy. You want to keep a low profile. I have a job, I

work. I'm seen in the community as a working class stiff, I don't

want to be known as someone who sells pot.

How much money do you make?

With a six-light scene I grow,

conservatively, six pounds every three months. That's four harvests

a year for 24 pounds a year. Multiply that by $4,000 and you

get around $100,000 -- cash. Then there's more from the people

I set up with grows. I make plenty.

It's NOT ALL indoors

by

ARNO HOLSCHUH

WHILE SOME GROWERS HAVE MOVED

INSIDE to avoid discovery by law enforcement, many have not.

That's why this year -- as every year for the past decade --

has brought another season in Humboldt County for the Campaign

Against Marijuana Planting.

![[photo of sheriff's trucks full of marijuana]](cover1108-sherifftrucks.jpg) Depending

on whom you ask, CAMP is either making Southern Humboldt a hard

place to grow pot or just a hard place to live. Law enforcement

officials say the joint state and county marijuana eradication

program cuts the amount of marijuana harvested in Humboldt County

and deprives growers of tens of millions of dollars. Some residents,

however, see CAMP as an invading army in their own backyards. Depending

on whom you ask, CAMP is either making Southern Humboldt a hard

place to grow pot or just a hard place to live. Law enforcement

officials say the joint state and county marijuana eradication

program cuts the amount of marijuana harvested in Humboldt County

and deprives growers of tens of millions of dollars. Some residents,

however, see CAMP as an invading army in their own backyards.

Complaints range from horses

being spooked by low helicopter overflights to allegations of

warrantless searches. The result is an atmosphere in which many

citizens do not trust the law enforcement organizations charged

with protecting them.

"People in Southern Humboldt

County do not trust the sheriff based on the way marijuana is

handled," said Mark Harris, an attorney whose practice consists

exclusively of marijuana defense. He said there are "quite

a number of regions in the county where the last person someone

thinks to call if there's a problem is the sheriff."

And suspicion is a two-way street.

"I've had CAMP agents on

the stand testify that they regard people in Southern Humboldt

as suspects as a general rule -- just because they live in a

rural area in Southern Humboldt," Harris said. "There's

a clash between that culture out there in the hills and law enforcement

in general."

Running parallel to the decade-long

fight about how appropriate CAMP's tactics are is another debate

over whether the program even works. While CAMP destroyed 15,360

plants in Humboldt County last year, Harris said it remains unclear

whether that meant any less pot was hitting the market.

"The season begins, the

helicopters fly, people try to document a host of civil rights

violations, the season ends. The season begins next year and

the same thing happens again. I have not seen any change in the

level of marijuana use or planting in the county," Harris

said. "There's a sense of futility."

That's not how law enforcement

sees it. Humboldt County Sheriff Dennis Lewis said he believed

CAMP has done "a fairly effective job [on reducing] the

outdoor grows" and had forced marijuana cultivation indoors

(see cover story).

CAMP found 100 outdoor gardens

last year alone. Those who still grow outside constitute a uniquely

old-fashioned class of small growers, said Mike Van Winkel, spokesperson

for CAMP.

In a telephone interview from

Sacramento, Van Winkel said that of all the places CAMP goes

to eradicate pot every year, the North Coast is the only location

that still harbors the old-fashioned "mom and pop"

grows.

"Growers in Humboldt and

Mendocino tend to be traditional: owner-operated with a couple

hundred plants being considered a big grow. That pales in comparison

to the Bay Area or the Sierra foothills, where grows are in the

tens of thousands," he said.

Marijuana eradication may be

headed for a shakeup in Humboldt County, however. In past years,

the Board of Supervisors has accepted CAMP funds with a 3-2 vote.

Fifth District Supervisor Paul Kirk, a CAMP supporter, is not

seeking re-election next March. That opens the field to a candidate

who may think differently about CAMP.

"If the helicopters fly

over people's houses more than once during each year's campaign,

I'm not for that," said Vic Taylor, who is running for Kirk's

seat. Taylor, a data collection and program compliance supervisor

with the county, said he supports marijuana eradication in principle,

but doesn't want drug policy to create "a war zone for innocent

civilians."

There may be as many as six

or more candidates for Kirk's seat and others are very pro-CAMP.

"I support CAMP,"

said Ben Shepard, a retired teacher who announced his candidacy

Nov. 5. He said he has good reason to. As a rural landowner,

he had to call CAMP to destroy gardens he discovered on his own

land.

"If there were no CAMP

program, I feel gardens would be more prevalent," Shepard

said.

IN

THE NEWS | ARTS! ARCATA | CALENDAR

Comments? E-mail the Journal: ncjour@northcoast.com

© Copyright 2001, North Coast Journal,

Inc.

|