|

by BOB DORAN

See also these

features at the end of this cover story:

From marshland

to post-industrial wasteland: Historical timeline of the Balloon

Tract

What's next

for the Balloon Tract?

THE BALLOON TRACK TRACT, that

slice of land between Eureka's waterfront and the elbow of Broadway

and Highway 101, is a mystery to many. Even its name is confusing.

(The "tract" actually got its name from the railroad

"track" that borders the site in the shape of a giant

hot-air balloon. [See

aerial photo in article below.])

What was once a bustling industrial

hub on the waterfront has fallen on hard times. The railway yard

slipped into disuse years ago. The structures have fallen into

disrepair. Oil soaks the ground. Weeds run rampant. Since overgrown

vegetation and abandoned buildings provide a haven for Eureka's

homeless and a party place for drug users, most people steer

clear of the area except those who sneak in to illegally dump

loads of trash. [A historical timeline of the Balloon Tract

appears after this article]

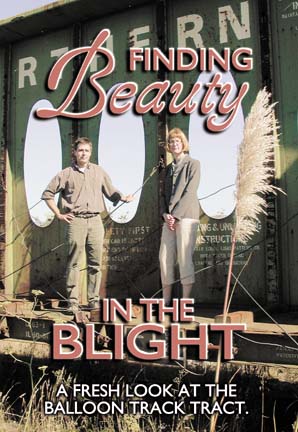

But Cindy Hooper [at right, in above title photo] an art professor at College of the Redwoods who

specializes in delicate oil paintings of "overlooked and

maligned places," landscapes strewn with trash or marred

by broken buildings finds beauty amid the blight. To celebrate

the much maligned parcel, the artist/professor became the prime

mover behind The Balloon Tract Project: An Exploration of

Misintentional Landscape Use, an installation that opened

last week down the street from the old railyard at Humboldt State

University's First Street Gallery in Old Town.

![[photo of painting by Cindy Hooper]](cover1011-hooper.jpg) "Residual Appeal

2000," painting by Cindy Hooper. "Residual Appeal

2000," painting by Cindy Hooper.

The balloon-shaped tract has

been in the spotlight several times over the last few years.

In 1999 the owner, Union Pacific, agreed to sell to the giant

retailer, Wal-Mart. Controversy erupted over the wisdom of big

box stores in general and, in particular, using a piece of land

adjacent to the waterfront for retail purposes. The issue was

ultimately resolved at the ballot box with the defeat of Measure

J, an initiative that would have changed the zoning for the area

to commercial.

Last year the tract hit the

headlines again when the Eureka City Council shocked many observers

by refusing a $3 million gift from businessman Rob Arkley and

his wife, Cherie, who sits on the council. The money was to be

used to purchase the parcel, clean it up and develop it for light

industry, a park and a parking lot.

Hooper and her team of College

of the Redwoods professors from several disciplines who worked

on the current "Balloon Tract Project" steered clear

of those controversies, however. They focused instead on the

area's landscape and the way the land historically has been used

and abused.

Hooper sees the interplay "of

beauty and blight" as one of the primary subjects in her

work.

"These overlooked and maligned

places and objects can actually have a very formal abstract beauty,"

she said in a conversation at the gallery where she was supervising

the exhibit installation. "They are full of meaning and

aesthetic merits and can be explored and understood through a

variety of different perspectives.

"Humans have had a tremendous

impact on the land and to avoid that in art is being overly idealistic.

There are certainly many places here in Humboldt County where

you can look at a view and not see human intervention, but in

most places it's there."

Hooper drew inspiration from

an organization called the Center for Land Use Interpretation

based in Los Angeles, an interdisciplinary group combining art,

geography, sociology and other disciplines.

![[photo by Jim Pegoda]](cover1011-pinkshoe.jpg) "Pink Shoe (I didn't Place

it There)" by Jim Pegoda "Pink Shoe (I didn't Place

it There)" by Jim Pegoda

"When I walked into the

galleries and offices for the Center for Land Use Interpretation

[CLUI] in Los Angeles, I said, `Whoa, this is wonderful.' They

were expressing in a conceptual way the same issues I'm trying

to express with paint. I felt an immediate kinship."

Even before Hooper found out

about the CLUI she was exploring the Balloon Tract as a landscape

painter.

"I've been a painter of

industrial sites for a while. I don't know why, but they inspire

me. I'm interested in examining the way humanity shapes the land

by their actions on a grand scale that can be comparable to the

forces of nature."

She is also part of a second

show running this month at the First Street Gallery. Disruptive

Topographies features her work and paintings by two kindred

spirits, Erling Sjovold and Jerry Smith. All the work was produced

during a CLUI residency at an abandoned military base in Wendover,

Utah.

"A lot of the motifs that

you find at the Balloon Tract, the oil drums, the barrels, the

piles of trash are like what you find at Wendover," said

Hooper. "It's like 100 square miles of Balloon Tract.

"I think what most fascinates

me is the juxtaposition of incredible natural beauty and ravaged

industrial places the remnants of our post-industrial consumer-based

culture. The stark interplay of degradation, reclamation and

natural beauty is an ironic contrast that I find of interest

as an artist.

"The Center is very much

interested in abandoned and overlooked industrial sites and in

investigating these places," she said, adding that CLUI

has funded a show similar to the Balloon Tract Project at San

Francisco's Yerba Buena Center dealing with industrial sites

around San Francisco Bay.

"These are areas that are

absolutely essential to the infrastructure of our culture, but

they're also places people don't want to deal with," she

said.

"One of the things we found

was that this is a spot that many consider as blight, yet it

has a value," said Dave Bazard [at left, in top title photo],

a geology professor who worked on the project. "And that

value is not necessarily just as a site for future industrial

activity, for a Wal-Mart or even a park. It's a value for its

history, for what's in its subsurface, for the geologic story

that can tell us how our area was shaped, the archaeological

and sociological aspect.

"The whole Balloon Tract,

everything west of Broadway, was once a salt marsh similar to

what you see as you go over the Samoa Bridge on Gunther Island

and Woodley Island," said Bazard. "A railroad was put

around it and eventually it was filled in."

He found that an examination

of the area's geology spilled over into a history of its uses

and into an examination of the pollution and its clean up.

His job was not an easy one.

When he went to the Office of Environmental Health and asked

for the Balloon Tract file, they showed him a four-foot long

shelf full of reports from consultants. His task was to boil

down the mountain of data to a few "digestible" panels

that a layman can understand.

Bazard concluded from his research

that by the mid-'70s, the use of the rail yard was in serious

decline. The unused buildings were falling apart, the old roundhouse

had collapsed.

"That was also around the

time when they first started looking at the run-off from the

site," said Bazard. Every time it rained, oil and grease

that had spilled on the ground over the years would wash out

of the contaminated soil, draining oily water into the slough,

then into the bay.

"Up until that time the

thought was, `Well this is industry. This is what we do.' It

was accepted. As environmental awareness mushroomed in the early

'70s, the thinking changed."

In 1974 the Regional Water Quality

Control Board took a look at the site and did not like what it

found. Southern Pacific was asked to take countermeasures that

included installation of an oil-water separator.

Further remediation since then

has removed the bulk of the oil that was getting into the bay.

And since Union Pacific only uses the site as storage for a few

rusting locomotives and cars, there is no new pollution associated

with the railroad.

"There is still industrial

pollution," said Bazard, but that's not the only problem.

"Even though it's no longer an industrial site, the pollution

has been incrementally added to by dumping. People leave oil

drums, then there are the lead acid batteries from cars."

At this point the only clean

up of hydrocarbon contamination is what is termed "passive

remediation," relying on the natural breakdown process.

Any future development will require a major clean-up process.

A prime example is Bunker C,

the old oil storage tank.

"You walk in there and

a black ooze comes up, so obviously there's still something in

there," said Bazard. He explained that a cement pad underneath

prevents contamination of ground water, "but at some point

someone will have to remove it all.

"Whoever takes it on will

have some serious work to do. When you buy commercial property

that's contaminated you accept the liability for cleaning up

the contamination."

"But we don't want to overdramatize

or sensationalize the problems with contamination," said

Hooper. "This is certainly not a superfund cleanup site.

There have been remediation efforts and there are ongoing monitoring

efforts. In the large view [the contamination] is not that egregious."

Bazard pointed to other sites

along that waterfront that are much worse, places with lingering

PCBs, lead contamination, heavy metals and other toxic substances

that don't seem to be a problem in the Balloon Tract.

A portion of the exhibit supervised

by C/R biology professor Ben Hawkins examines the ecology of

the area.

The plant life is a classic

example of invasive non-native species overrunning natives. Himalaya

berries, pampas grass and fennel are among the non-native plants

that have colonized the site.

The slough may have been converted

into a drainage ditch, but it's still the home to egrets, herons,

kingfishers, possums and even otters.

There's a touch of tongue-in-cheek

humor at work when the exhibit discusses the area's other inhabitants.

For example, Hooper refers to the homeless encampments that dot

the site as "nests."

While she concedes that there

was no study to establish firm numbers, a "casual estimate"

is that 20-30 people call the area home.

"I think that the general

public sees the Balloon Tract as some sort of a problem, but

in a way it solves a problem for the community in that it does

provide a quiet refuge for homeless people where they are out

of sight."

Both Hooper and Bazard emphasize

that the intent behind their project was to present facts about

the area in a neutral fashion, not to make some social or political

statement.

"It's easy to take a vacant

lot with homeless people and some pollution and tell people it's

bad," said Bazard. "The challenge was to draw the value

out of it and lead people to go beyond black-and-white thinking.

"Understanding a place

like this takes some thought. There may be certain sadness to

the site, but there are not necessarily good guys and bad guys.

You have to get beyond the controversy and knee-jerk reactions."

The hope is that the project

will lead to meaningful discussion in the community and to new

inquiries.

"The more we researched,

the more we discovered," said Hooper. "We invite the

public to take up the components of the project that are not

finished, to find this space and others like it and find the

meaning in these overlooked and underutilized places."

The

Balloon Tract Project: An Exploration of Misintentional

Landscape Use will be on display through Nov. 3 in the East

Room of Humboldt State University's First Street Gallery, 422

1st St., Eureka.

In conjunction with the exhibit,

the gallery presents a talk by Matt Coolidge, director of the

Center for Land Use Interpretation on Thursday, Oct. 25, at 6

p.m. Exhibiting artist Erling Sjovold will give a gallery talk

on Saturday, November 3, at 4 p.m. For more information call

443-6363. The Website for the Center for Land Use Interpretation

is at www.clui.com.

From marshland to post-industrial wasteland

![[aerial photo of Balloon Tract]](cover1011-aerial.jpg)

Aerial photo by Merle Shuster, 1952

1850 -- Marshland

and a network of sloughs occupy the site west of the Eureka town

site.

By 1888 -- The western

side of the marsh is filled and a bayside rail line established.

The tidal marsh and Clark Slough remain undeveloped.

By 1915 -- Eastern

and northern portions of the tidal marsh are filled with a mixture

of silt, sand and gravel. The site is used as a railroad yard

for refueling and repair. Bunker C, an oil storage tank, is constructed.

1931 to 1939 -- Southeastern

corner of the site (near Washington Street and Broadway) leased

by Northwestern Pacific Railroad Co. to Richfield Oil Co. and

General Petroleum Co. and two above ground fuel storage tanks

are installed.

1946-1947 -- The last

remaining tidal marsh is diked off. Dredged material from the

bay is used as fill.

1954 -- Above ground

storage tanks installed in the Bunker C site to store diesel

fuel used by modern locomotive engines. By this time Clark Slough

appears as a drainage ditch.

1974 -- The Regional

Water Quality Control Board orders spill prevention, control

and a countermeasure plan. Northwest Pacific Railroad estimates

in a report that 5,000 gallons per day of oily storm water is

discharged into Humboldt Bay with rain runoff.

1975 -- The water

board orders discharge of oily storm water runoff discontinued

and countermeasures for release of petroleum hydrocarbons to

Humboldt Bay implemented.

1976 -- NWPR installs

an oil collection system and above ground oil-water separator.

1984 -- The on-site

diesel storage tanks are no longer in use. A tank truck is used

to fuel locomotives.

1986 -- Southern Pacific

Transportation Co. purchases NWPR, but discontinues operations

at the Eureka rail yard site. Eureka Railroad Co., formed, leases

the railroad yard from Southern Pacific to continue railroad

line operation.

1987 -- Aerial photographs

show the site as mostly inactive. The roundhouse has been demolished,

many of the buildings and other structures dismantled or in disrepair,

and most of the southern area overgrown with brush and grass.

The fuel distribution facilities have been removed.

1988 --

Site use has decreased significantly. Water board order for

oil collection and discharge expires and discharge system is

abandoned.

![[photo of disabled oil-water separator]](cover1011-oilseparator.jpg) [At left, a disabled

oil-water separator.] [At left, a disabled

oil-water separator.]

June 1988 --

At the request of Public Health Department, Southern Pacific

arranges to have four underground gasoline storage tanks removed.

No detectable concentrations of petroleum-associated compounds

are found in the soil surrounding the tanks. However, groundwater

samples contain up to 0.69 milligrams per liter (mg/l) benzene,

1.10 mg/l toulene, and 1.2 mg/l xylenes, all components of petroleum.

An environmental consultant states that the contamination is

likely from an off-site underground storage tank to the east

(near Broadway). The tanks are removed and no further investigation

is conducted.

July-Nov. 1988 --

An environmental impact statement is prepared for construction

of the Humboldt County Jail at the Balloon Track site. An investigation

of soil and groundwater contamination from shallow soil surveys

and groundwater monitoring wells indicates the presence of oil,

grease and petroleum hydrocarbons. Three samples exceed safety

thresholds for lead. The environmental consultant recommends

that the site be cleaned-up before the property is developed.

Another site is chosen for the jail.

1989 -- The water

board requests that Southern Pacific Transportation Co. assess

soil and groundwater quality beneath the Balloon Track Site.

An environmental consulting company is retained to assess the

site, remove potentially hazardous materials and make recommendations

for further clean up.

1989-1990 --

Consultants hired by Southern Pacific perform preliminary investigations

and cleanup activities at the site; about 980 gallons of uncharacterized

oil are removed from the site. Waste materials are either transported

to a recycling facility or disposed at a facility in Kettleman

City, Calif. Approximately 3,500 gallons of oily wastewater are

removed from the oil-water separator system and transported to

a recycling facility. The inoperative oil-water separator is

sealed.

June 1990 -- Aerial

photograph shows that most of the railroad tracks, except along

the northwestern site boundary, have been removed.

1999 -- Soil and groundwater

analyses of samples collected near former underground

storage tank show contamination levels below legal limits. Accordingly,

active remediation in this area is deemed unnecessary.

1999 to 2001 -- Continued

site evaluation. Consultants hired by Wal-Mart had intended to

study the presence of both heavy metals and arsenic in a study

proposed in 1999. Consultants for Union Pacific (formerly Southern

Pacific Transportation Co.) continue to monitor wells quarterly

and report the results to the water board.

Summarized from

maps and aerial photographs displayed in the "Balloon Tract"

exhibit at HSU's First Street Gallery and from the reports of

Geomatrix, an environmental geology consultant to Southern Pacific.

What's next for the Balloon Tract?

With 29 to 30 usable acres adjacent

to the Broadway/Highway 101 corridor and the bay, the Balloon

Tract is ripe for development, but the property has to be cleaned

up first that will not be an easy task.

The city and property owners,

Union Pacific, are looking at clean-up in three phases. Phase

one, already under way, is clearing some of the trash and vegetation.

"The summer of 2000 we

had a couple of fires," said City Manager Dave Tyson. "One

was kind of major -- three or four acres within the Balloon Tract

itself. We think it was transient-caused. It created quite a

bit of concern for the [Eureka] Chamber of Commerce, and of course

our fire marshal and businesses in the area, because it came

fairly close to the businesses that operate near there."

Tyson said one of the city's

primary concerns is the portion of Eureka's population that makes

frequent use of the property -- transients and drug users.

"As part of our abatement

process with Union Pacific we've indicated our fears for employees

who have to go in there -- police mainly, but also firemen who

have to go in the because of drug overdoses or fires, problems

that occur."

Union Pacific applied to the

Coastal Commission and the Department of Fish and Game and received

permission to remove some vegetation. Last spring rushes, berries,

fennel and other foliage that covered much of the parcel were

cut back. Under the terms of the permit, what was done was akin

to mowing a lawn -- and the results were about as permanent.

"Because of the time of

the year when it was cut, a lot of it has grown back," Tyson

acknowledged.

Phase two of the clean-up is

removal of debris -- piles of garbage, dirt, concrete and other

construction materials dumped there illegally. Union Pacific

removed some of the piles along with the vegetation, but like

the re-emerging weeds, it did not end the problem.

"It's a big vacant unpatrolled

piece of property and there has been quite a lot of dumping there,"

Tyson said. The debris removal is also complicated since some

of it is contaminated, which requires testing and more elaborate

disposal than simply hauling it to a landfill site.

"Then there's the removal

of the buildings," Tyson continued. "There are three

or four buildings on the site that need to be removed and [the

owners] are seeking permits to do so. The city is working with

Union Pacific to take them down as they are a fire danger as

well as danger to the public as an attractive nuisance."

The city will act as lead agency

seeking permits from the four or five overlapping government

regulatory agencies involved, including the Coastal Commission.

"The final phase, the clean-up

of the site, will require Union Pacific to work with the city

and more importantly with the state Regional Water Quality Control

Board," Tyson said.

"The [water] board has

quite a bit of say over the property because it is contaminated.

It is known to be affecting groundwater with those contaminates.

Not that it's creating a problem with drinking water because

that all comes through our water treatment plant. But there is

the possibility that it could be affecting the bay water as well

as the aquifers beneath the Balloon Track."

And once the site is cleaned

up, what then?

"At this point there is

no development proposed there," said Tyson. One problem

with planning a development is the zoning. Because it was once

a rail site governed by a public utility, the zoning is "P"

for public, which limits development.

Schools, city halls, jails and

wastewater treatment plants are among acceptable public uses.

Aside from a scuttled plan for relocating the jail there, no

other public use has been proposed. And it's unlikely that anyone

will resurrect the rail yard.

"Union Pacific is no longer

operating a rail operation in the area. A few years ago the Northern

Coast Rail Authority indicated that it has no need for the rail

yard other than [use of] the rails that run along the side of

the property."

While the public rejected Wal-Mart's

Measure J, which would have forced a change in the zoning from

public to commercial, it seems likely that a zoning change of

some sort will be required for development.

"The city, working with

some interested groups -- Friends of Humboldt, the Northcoast

Business Leaders Roundtable, our planning commission, our redevelopment

agency -- have been talking about changing the zoning of the

property and what that would mean," said Tyson. "That

has yet to take off as far as discussion in the community, but

I'm sure it will."

What uses are being suggested?

"Industrial uses, not heavy

industry, but light industrial manufacturing. And there's talk

about saving some of it for recreational use."

Whatever happens there will

be under the watchful eye of the public agencies that protect

the coastal zone and wildlife habitat.

"Most likely if development

was to occur there you would have to mitigate for the loss of

the marshes with more wetlands," said Tyson.

"It's an area we need to

work on as a community. The community has to get involved and

provide some guidance to the elected officials and staff as to

how it fits into the city's development. It is a key piece of

property; it's one of the largest available in our community

for development. We need to define what we'd like to do with

it."

IN

THE NEWS | ARTS! ARCATA | CALENDAR

Comments? E-mail the Journal: ncjour@northcoast.com

© Copyright 2001, North Coast Journal,

Inc.

|