| |

|

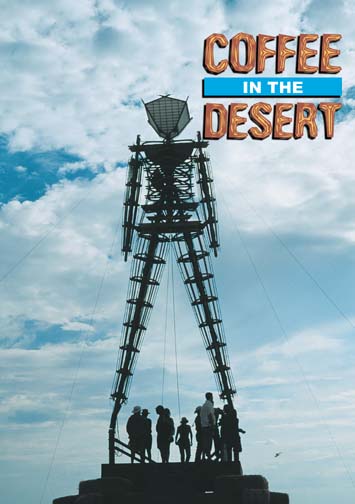

"Coffee Camp," with Black Rock City behind. |

Black Rock City's only café. |

It took several trips over the course of a week to truck in everything. The final load Friday carried the last 1,600 pounds of coffee and four Muddy Waters employees -- Gabe Adams, Chris Nichols, Alecio Lopez and Jonathon Thomas -- as well as one Journal reporter, to record the event for posterity.

After the initiation at the gate, we stowed the coffee and walked down to the café, staffed all week by volunteers, to work 7 to 11 p.m.. It was a shift that would not usually be busy at most coffeeshops, but Burning Man attendees keep strange hours, and the lines for drinks were easily 50 bodies deep. Team Muddy Waters, a model of efficiency, whipped out lattés, cappuccinos and macchiatos with speed and grace. The four hours flowed by quickly, and the newly caffeinated crew went out for a little stroll.

The five-square-mile city is set up like a clock dial, with radial streets corresponding to the times of the day intersected by streets named after body parts. Our camp was at 6:15 and Brain Street. At the very center of the circular city, of course, is Burning Man.

The streets overflowed with people -- dancing, singing, playing music, sitting or standing in line for porta-potties. (Imagine a county fair in Calcutta.) There were several raves -- throbbing music and writhing bodies -- that never really stopped. If one slept at all it was to the continual thump of electronic bass somewhere, everywhere.

Muddy Waters' coffee roaster J.T., sporting a new mohawk, was immediately accepted as a native, but the rest of us were conspicuous in our normalcy. We passed several old motorized living room couches with wheels attached for cruising enjoyment. And yes, there were flying saucers, people wearing nothing but paint, and several attendees dressed in full leather armor. Soon we learned it was impossible to be an outcast -- everyone fits in.

To call any one person, item, art display or action at Burning Man surreal would be unjust. The entire city was surreal. Every morning about 8, a car would drive around announcing over a loud speaker, "Black Rock City is closed. Pack your tents and go home. Burning Man is over. Please leave," which everyone ignored. The only day there was no announcement was Monday when Black Rock City actually closed.

![[photo of Ranger on steps]](cover0914-altar.jpg) |

A dust devil of a different sort.

Revelers enjoy the atmosphere of freedom. |

| A Radio Flyer Wagon family. | ![[photo of wagons]](cover0914-wagons.jpg) |

There was one strict rule of life in the city of Burning Man: You can barter for, beg or borrow things you may need -- and many do -- but if you are caught selling anything for cash, you will be promptly ejected. (The café and an ice vendor were the only exceptions to this rule.) The Burning Man website plainly warns you ahead of time that you must bring everything to make it through your stay, including all food and water.

Friday night the playa received a cold, soaking rain. The irony over being soaked in the middle of the desert soon gave way to bone-chilling cold as the night's temperature dropped near freezing and we were forced into the tent for an early night.

The Muddy Waters crew made up for it the next night. We left camp together to see the 52-foot man get torched but were quickly separated. Comparing notes the next morning we realized that while not physically together, we had all had similar experiences of being overwhelmed by sounds and images of fire-breathers, dragons, strippers, priests and satyrs.

The Burning Man himself seemed almost anticlimactic. When the moment arrived, much of the crowd was drawn away by "Dr. Megavolt" -- a man in an insulated suit who was continually being zapped by the lightning being emitted by two tesla coils atop an RV. As the RV trundled across the playa, it began to accumulate an entourage of bicyclists lit with glow sticks, cheering as the purple electricity crackled and buzzed into the air.

I followed Megavolt to the edge of the city where I next saw a group of people run by carrying signs with letters on them that spelled "SPACE LOUNGE." As they passed, a man with a megaphone turned to the group and ordered, "CLEAN UP!" With a touch of the Keystone Cops, the group rearranged itself to spell "C-L-E-A-N U-P" -- the letters S, O, G and E temporarily out of service.

"To the Space Lounge, comrades!" the leader barked and all 11 letters boarded a vehicle that may have begun its life as an automobile but which had been modified --Astroturf and bar stools -- into a cocktail lounge.

![[photo of Black Light District]](cover0914-night.jpg) |

The 52-foot man burns as the crowd of 25,000 watches. |

Next I encountered a glowing orange and pink dome. When I entered I found a large man in a silver diaper with a sign around his neck reading, "Id," and a woman in a Superman costume ("Superego") having a lively argument about not much at all.

"Finally, the ego's here," the man said. "Welcome to your own brain. Are you familiar with Freud? This is the Superego, the moral control freak of your brain. I'm the Id, and I tell you what you'd really like but the schoolmarm over there won't let you have. It's your job to mediate. We're discussing your inability to reach decisions. Ready? Go.

"By the way, would you like some Nutella?" he added, offering me a jar of chocolate goo.

Burning Man is, as much as anything else, an atmosphere of freedom.

"I think people come here purposefully to lose inhibitions," Hentz later philosophized. "We're on this incredibly large flat surface and I think that gives people a template for the freedom they have to express themselves. It's an eccentric artistic expression -- almost an overexpression. People go out of their way to change who they are in their real life and let out their fantasies, or to take part in something a little bit risky."

The experience of Saturday night melted into the experience of Sunday -- a constant stream of images, some garish, some eerie, some witty, all very weird. Word came in about mid-morning that only about a third of the coffee brought to the event had been used and negotiations ensued regarding how to dispose of the surplus.

Monday the crew broke camp and left, packing up tents, loading the extra coffee and dismantling the café. Hentz said that while the Burning Man contract was "a for-profit venture," the company's real gain was better measured in experience than money.

"We would definitely do it again," he said.

Comments? E-mail the Journal: [email protected]

© Copyright 2000, North Coast Journal, Inc.

![[photo of Muddy Waters delivery truck]](cover0914-muddy.jpg) The fully-loaded Muddy Waters delivery truck arrives.

The fully-loaded Muddy Waters delivery truck arrives.![[photo]](cover0914-desert.jpg) The Unburnt man

The Unburnt man![[photo of campers]](cover0914-camp.jpg)

![[photo of coffee shop]](cover0914-coffee.jpg)

![[photo of revelers]](cover0914-group.jpg)

![[photo of burning man]](cover0914-burn.jpg)