|

Critical Condition Stop by Mad River Hospital some sunny day and take in the scene. Rising up from the parking lot, a multistory structure of gleaming steel pierces the sky -- its outline looking curiously like a cathedral. Awe inspiring it may be, but as you look closely you notice that nobody is working on it. And if you happened by last week -- or last month for that matter -- you would have seen the same eerie emptiness.

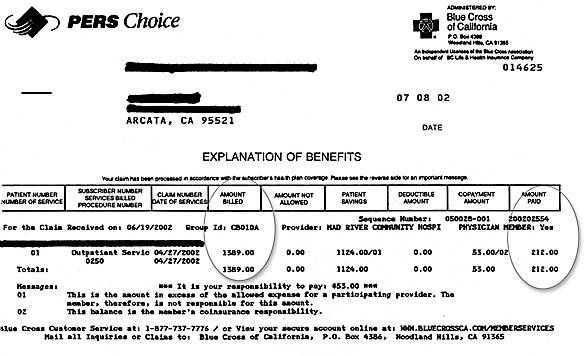

Take a moment to understand how we got into this mess. Once upon a time -- back in the 1960s -- hospitals were chronic poor relations, always begging for money. Holding raffles and bake sales for new equipment was common. And because they were such money-losers, hospitals were usually sponsored by charitable organizations or local municipalities. Nobody in his right mind would consider building a hospital to make money. Then came Medicare and Medi-Cal. Suddenly the old and the poor had money for their health needs. And when the demand overtook the limited hospital capacity, the federal government offered money to build new ones. For the next two decades, the health care system swelled like bread dough in a warming oven. Intensive Care Units were established, new surgical equipment poured into even small hospitals. Locally, CT scanners -- cutting edge technology at the time -- were soon humming in all Humboldt County hospitals. If the technology existed, people and hospitals wanted it, and they were buying it without bake sales. The new expanded system was quite user-friendly. In the 1970s it was not uncommon for grandma to be admitted to the hospital while the family took a much needed vacation. Granny's usual ill-health had not worsened, it was just that nobody would be home to watch her. And with Medicare paying the bills, you couldn't find a better baby sitter. Despite obvious abuses of the system, many people were getting their first care in years. Cataracts were removed and new lenses implanted; irregular hearts got pacemakers, 60-year olds with lousy coronary vessels got bypass surgery, and diabetics finally got their blood sugar under control. It was, in many ways, a golden age. But the golden age was costing more gold than Congress had anticipated, and in response to the spiraling costs, government increasingly cut back on its largesse. Time and again, reimbursement was trimmed -- providing less money for hospitals, doctors and the rest of the now huge medical establishment. Hospitals fought back, using "cost shifting." If the government was going to reduce its payments, other folks would just have to make up the difference. Insurers like Blue Cross, and people without insurance, found themselves socked with increasingly higher bills. Three dollar aspirins were a reflection of the new realities. But we're getting ahead of ourselves. More than 20 years ago, medical economists came to realize what was driving the ballooning costs of medical care: third party payers. This referred to the system where medical providers offered services, patients used them, but somebody else -- a third party -- picked up the tab. It was a system that fairly begged for abuse. It would be like sending your teenager to buy a car with somebody else's credit card: Neither the dealer nor the teenager has any incentive to be cost conscious. One "fix" for the broken system was managed care. If a third party was going to pay the bills, by George, it would also regulate the care. Insurers would no longer be simple bill payers. Expensive surgeries would not be covered unless a second physician agreed it was necessary. Routine hospitalizations needed pre-approval, and visits to expensive specialists had to be approved by a primary-care "gatekeeper." This helped somewhat, but still the costs rose. Finally, inevitably perhaps, a new voice was raised. "Let's turn the system over to businessmen, they know how to control costs." Which almost gets us to the heart of our tale. But first a digression ... Several months ago, a physician I know well walked sheepishly into the emergency room. He'd been suffering chest pain for several hours -- a pain he initially dismissed as heartburn. But it hadn't gone away with antacids or acid-blockers. Realizing what he'd advise his own patients to do, he sought care. For the next three hours, he lay in the ER while nurses, respiratory therapists, and laboratory technologists fretted over him. A $6,000 EKG machine -- with built-in computer analysis -- provided a written record of his heart's activity. His blood pressure, pulse and oxygen saturation were constantly monitored by a $4,000 device that radioed the results to a monitor at the nurses' desk. Twice during his stay blood was drawn and analyzed for any hint of heart-muscle damage. While he lay in bed, a complete blood count and a comprehensive chemistry panel were performed in the laboratory. He was treated with two different types of medication -- an attempt to reduce his discomfort and diagnosis his symptoms. And always, he was under the watchful eyes of a nurse. At the end of three hours, he was discharged. His pain was gone, and his heart appeared to be fine. Later he received a statement from his insurance company. The total hospital charges for that eventful night were $1,389. Of that bill, Blue Cross was going to pay $212, leaving the physician responsible for $53. The remaining $1,124 of hospital charges were simply not being paid. Two hundred and twelve dollars. Think about that. Twenty-three blood tests, an EKG, two different medications, constant care by an RN, intermittent care by laboratory personnel and respiratory therapists, constant monitoring of vital signs, and Blue Cross was willing to pay only $212.

To put that into perspective, I called the dealer to find out what I'd have to pay a mechanic to work on my '98 Subaru. Answer? $69 an hour. One person, 69 bucks an hour. That's almost precisely what Blue Cross is willing to pay for the services of a fully equipped emergency room, a slew of blood tests, several medications and the care of three fully licensed health professionals. Might that explain Mad River's Cathedral Skeleton? But if Blue Cross is being stingy with its payments, what is it doing with the money it collects from subscribers? This brings us to the last part of our story. Once upon a time there was a company called Blue Cross. It was a "nonprofit" corporation, meaning that it had no stockholders and made no profits. Each month it collected small sums of money from countless policy holders and returned it when one of them got sick. Money in equalled money out, minus a little for expenses. Mind you, those "little for expenses" were a tidy sum. It paid excellent salaries, bought corporate jets, plush offices and the other perks that captains of industry expect. Nevertheless, the bulk of the money coming in was supposed to be used for health care. Stuffing it into their pockets would have been criminal behavior for the corporate officers. But when the cry "let the businessmen do it," erupted, Blue Cross was right there. In 1996, the stodgy Blue Cross became the elegant Wellpoint. Unlike its ancestor, Wellpoint was free to make as much profit as it could. It could charge as much as people were willing to pay and pay out as little as it absolutely had to. And everything it didn't pay out was, well, profit. Let me say that again. Unlike the old Blue Cross -- which was obligated to use money collected to pay patients' bills -- the new Wellpoint could, in theory, take the bulk of "insurance" premiums and slip them to its corporate officers and stockholders. But they wouldn't do that, would they? Well ... Last year, 2001, the CEO of Wellpoint, Leonard Schaeffer, was paid $5,614,425 -- or just a tad over $100,000 a week -- not including stock options. Mind you, I do not doubt that Shaeffer is a hard working CEO, and I know that other CEOs are paid even more than he. But there is a crucial difference: The money Shaeffer was paid is money that could have been -- in my mind should have been -- used for health care. For his $5 million-plus, I suspect Shaeffer did not perform a single operation, apply a single Band-Aid, dispense a single medication. And he's not the only one with his hand in the cookie jar. Go to www.wellpoint.com and check the facts for yourself. There you will see the smiling face of CEO Shaeffer and discover that since its introduction, Wellpoint (WLP) has consistently outperformed the market. Even in today's down market, it is valued at nearly $10 billion. And what does it sell? Why, other people's work. Last year, its 145 million shares earned nearly $4 each. Stated otherwise, nearly $600 million of health care money was siphoned from the system into hands of investors. Does this seem rational to you? It seems mad to me. But in one way, at least, it makes perfect sense. It explains the magnificent Cathedral Skeleton gleaming in the summer sun along Janes Road.

Jay Davis is a physician and author in Humboldt County. COVER STORY | NEWS | CALENDAR Comments? E-mail the Journal: [email protected] © Copyright 2002, North Coast Journal, Inc. |

The fact is that for months now the steel skeleton has remained untouched. It stands as a mute testament to the precarious health of our medical system, a fitting symbol of what seems so promising but remains somehow out of reach.

The fact is that for months now the steel skeleton has remained untouched. It stands as a mute testament to the precarious health of our medical system, a fitting symbol of what seems so promising but remains somehow out of reach.