|

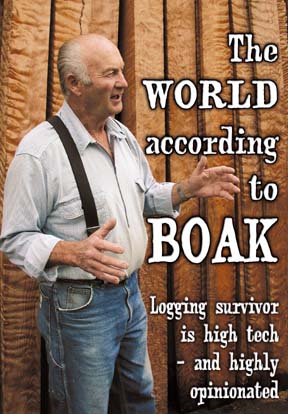

by JIM HIGHT by JIM HIGHT ON A FORESTED HILLSIDE NEAR BIG LAGOON, BILL BOAK'S $400,000 logging machine moves across swales and brush with the agility of a deer. An operator sitting in an enclosed cab swings the boom to place a gray rectangular device on the trunk of a Douglas fir. In a few seconds the slim green giant falls neatly on top of a pile of downed trees. It happens so fast Journal staffer Bob Doran and I wonder aloud if the machine is pulling the trees up by their roots. "There's a saw underneath, a big chain saw," explains Boak. "Look at the sawdust coming out of that," he says when the machine grabs another tree. "It's just `zip,' and they're gone." A couple hundred yards away, another big machine works through a pile of downed trees, clipping off their limbs and sawing them to lengths prescribed by an onboard computer. Before the day is done, the two machines working together will have turned about 150 young-growth trees into logs, ready for trucking to a sawmill. Boak, 76, has spent millions of dollars in the last 10 years on equipment like the dangle-head falling machine taking down trees and the processor spitting out logs -- and he has more of these machines on order. [Photo below right shows machine at work]

But Boak gets serious when he explains why this kind of logging is better than the old kind. "To do this much work, I'd have to have the woods full of people, all of them in harm's way," says Boak, who once lost a crewmember in a fatal accident. "We're trying to get rid of as much of the [manual] cutting as we can and pawn it off on the machines, although some falling is still done with chainsaws." The mechanized gear also allows Boak's crews to work faster and more efficiently than logging outfits using older equipment and methods -- and that's one reason Boak Logging is surviving and employing 30 to 40 people in what has become a very tough business (see "A Dying Breed," May 6). "[They're using] obsolete technology," says Boak, with a note of sympathy for the logging outfits that have failed. "God help me, in five years all this may be obsolete. Or maybe we won't need anything larger than this. Or maybe it'll all be helicopter logging in a few years. Then nobody but a huge corporation will be able to do it." Aside from being safer and more competitive, Boak says the mechanized logging in action here at Big Lagoon, along with the cable yarding systems his crews use on steeper ground, are better for the environment. "[The machines] travel this country and they don't dig it all up," says Boak, pointing to where the dangle-head falling machine had gone. The ground was still covered with forest litter, the sword ferns rumpled but alive.

"I think it's too darned bad that the world doesn't know the effort and money we're putting out to do things the right way," he says. Boak's assessment of the ecological impacts of mechanized clear-cutting will be less than persuasive to many. Even if the forest floor is not torn up as in the old days, clear-cuts still eliminate the overstory, or canopy, and leave open ground vulnerable to erosion, which can damage fish habitat in nearby streams. Streams may also be polluted from the herbicides sprayed on hardwoods and shrubs after a clear-cut. Biological diversity is diminished when forests are replanted as conifer plantations. And forest vistas enjoyed by residents and tourists are degraded. After 60 years in the logging trade, Boak has answers to these and almost every other objection to industrial logging. His viewpoints won't settle any arguments, but as a survivor in a struggling and changing industry he's certainly worth listening to. [Photo above left: Aaron Hooven repairs dangle-head while Bill Boak looks on] Destructive logging A third-generation logger from Washington, Boak went to work for his father, Theodore, in 1941 at the age of 13. His first job was tending a wood-fired steam donkey, a device used to pull logs from the woods. After serving in the military, Boak rejoined his father's business and soon moved with the family to Oregon, where they logged for various companies. Arriving in Humboldt County in the winter of 1952-53, the Boak family was shocked at the state of the industry here. "We thought Oregon was a little backwards, but when we got to California everybody's checks bounced," he remembers. Many timber companies cut and ran, went bankrupt or just wouldn't pay. And sketchy financial practices weren't all that was wrong. "There was a lack of care of the land and lack of care of the timber," says Boak. "They were wasting it like a blind dog in a butcher shop, taking a bite out of everything. They figured if they saved 60 or 90 feet out of an [old-growth] tree, that was fine." Yarding felled trees with cables -- a common practice farther north -- was rarely done here. Instead, tractors were ripping up the hillsides. "The Gulf War [of 1991] was not as devastating" as what occurred on some North Coast forests, says Boak. Reforestation methods were also primitive, Boak says. "Ten or 15 years before then, the state of Washington was planting trees two-feet high," Boak says. "California was aerial seeding or hand seeding." And these methods were improvements over what California timber companies had done before, leaving the least valuable trees as seed trees. "That just breeds you another bad tree," says Boak. The Boaks worked for a series of companies, eventually contracting for more than 20 years with Louisiana-Pacific Corp. "We logged in Crannel (near Little River), we did Forest Service sales, Big Lagoon, the McKay Tract (near Eureka), wherever their holdings were," he says. Speaking for the industry

Boak recalls that the convoy nearly broke up partway across the country. Log truck drivers and their families were falling behind the faster passenger cars and having trouble finding the scheduled stopping places. "And we had politicians more worried about how they looked," recalls Boak. Boak argued for a 45 mph speed limit and more attention to the regular folks. "I said, `We're going to get these truck drivers and their wives up there and let them say hello to the people,'" recalls the logging boss. "And so we did." The high point of the protest for Boak was being escorted to the Capitol by local Teamsters and carpenter's union members. Government officials and the media were less receptive. "Walter Cronkite said, `I'm an environmentalist, the hell with you.' That's been the story of the timber industry." The park's expansion by 48,000 acres was authorized by Congress. Boak sat on advisory committees and testified before legislative bodies to influence forest policies. His general view of the process: most forestry legislation was based on "things that came out of a book that somebody wrote that they got out of a book that somebody else wrote. Lord knows whether the first person saw the woods or not." At one hearing in Sacramento or Washington, D.C. -- he can't remember which -- Boak lampooned the legislators' ignorance. "This was when we were just getting into leaving the snags for the bugs and for the woodpeckers and different birds," recalls Boak. "I [told] them that we were having a problem. The birds were getting in the bug trees and the bugs were getting in the bird trees. I went on and on, and the committee sat there so interested, [thinking] `What are we going to do to keep the birds out of the bug trees?' Well, the birds live off the bugs." But despite his contempt for book-schooled legislators, Boak acknowledges that bad actors in the timber industry also set the stage for California's tight Forest Practice Rules. "You can't lump the timber industry together and say they're all good," he says. "Someone put the `damn' in front of `damn logger.'" In 1998, Louisiana-Pacific offered its Humboldt County timberlands for sale, and the land was purchased by Simpson Timber Co., which soon became Boak's main client. "Simpson wasn't the only company bidding on it [and] I'm glad that Simpson bought it," he says. "They're a timber company, not a junk-bond outfit." Doran and I prod Boak for more of his thoughts in this vein, but he keeps his counsel. "I could say things that I don't want you to quote," he says. Bully on clear cuts Standing in the middle of a pitchy sea of logs and slash, Boak has plenty to say about the best ways to harvest and grow redwood and Douglas fir. "The name of the game in the timber industry is to produce as much wood per acre as we can," he says, describing how his mechanized equipment yields more wood than manual methods: The cutting machine saws the trees lower than a human being could manage a chainsaw, and the processor scales and cuts logs for minimal waste. "It's like eating a chicken," he says. "You don't just eat the drumstick and throw the rest away. We want to utilize everything we can." And while environmental advocates, many citizens and some foresters advocate selective logging, Boak insists that clear-cutting followed by reforestation is the best way to produce redwood and Douglas fir. "Thinning seems to be the political way to do it, but it's the worst way in the world to grow fir and redwood," he says. "You create a tree that starts growing more limbs down low. It grows shorter instead of taller and wider at the butt. You create an expensive logging job." As for the appearance of clear-cuts, Boak acknowledges that "Harvesting is rough work, and in the end it looks bad. "But should we expect landowners to leave as much timber on their land as they can [so there's] a view that we can call beautiful as we drive down the freeway?" he asks. "That's a pretty selfish way of looking at forestry, isn't it? You're looking at it in your own time, you're looking at it personally. "Should I try to move my program to something that wouldn't produce as much wood just because it doesn't look good?" he adds. "Looks has no place in forestry. You don't prune your orchard for looks. You take care of it in a manner to produce more apples." Despite his anti-government rhetoric, Boak seems reconciled with forestry regulation in California. "I like it all," he says, with what might be construed as a cheeky edge to his voice. Boak also seems somewhat confident that Simpson will continue to make the environmental trade-offs it needs to log at its chosen pace: several thousand acres annually -- virtually all young-growth timber -- on a land base of more than 400,000 acres. "[The company] has shade canopies, wildlife corridors, sections set aside for owls. They've been doing it for quite a while, and they're improving it." (Simpson is currently negotiating a multi-species Habitat Conservation Plan with federal resource agencies. See story below.) A target What bothers Boak, though, is the anger and hatred -- fueled by misunderstanding, in his view -- expressed by many people toward him, his family, his crew and his industry. Boak's logging equipment has been vandalized several times, with losses exceeding $100,000. "For three generations, I've been in the forest," says Boak. "It's the only life that I've ever known. And my children, unfortunately, that's all they've ever known, and now I got grandkids in the business." Boak had spoken often of his two sons, John and Bill, who co-manage the operation with him, and this was the first time I'd heard him express any regret about their coming into the business. "Well, in a way it is [unfortunate]," he says. "They already had a logging outfit, you might say. With the girls it was a different story. All the girls worked in our office, then went on to do their own things. The boys were just hung up with logging and they loved to log and were born to log, I guess. So they're there, but there are a lot better opportunities. "There is a lot squeezing you in the timber industry. You've got people breaking your windows, calling you names," he says. "I hope to see the day when people will say `Thank you for growing this timber. Thank you for growing the wood that we need to build our houses and schools and businesses.'" Jim Hight is a freelance writer based in Arcata. He can be reached at Simpson plans stir oppositionby JIM HIGHT Like Bill Boak, Simpson Resource Co. is a survivor of the decades-long downsizing in the North Coast timber industry. Since Simpson bought its first redwood timberlands in 1945, the Seattle-based company has outlived hundreds of rivals and today owns 416,000 acres in Humboldt, Del Norte and Trinity counties. Simpson employs about 300 people at wages averaging over $30,000 a year, and it provides a living for many contractors like Boak and his crew of 40. The manufacturing side of the company, Simpson Timber Co., employs another 380 in mills and offices. (Parent company Simpson Investment Co. separated the two entities in 2001.) But two-legged beings aren't the only ones dependent on Simpson's forests. The company's property is home to a large variety of fish and wildlife, including threatened species like coho salmon, which is barely hanging on in Northcoast streams. Simpson is now seeking 50-year permits from federal agencies to continue logging in and around the streams that coho and six other sensitive species of fish and amphibians depend upon. The stakes are high, if for no other reason than the sheer size of the company's holdings in northwest California. "They have such a large chunk of the landscape that they're almost like a national forest in their impact," says Tim McKay, director of the Northcoast Environmental Center. In its proposed Aquatic Habitat Conservation Plan (AHCP), Simpson lays out a vision for protecting and improving habitat conditions for coho, chinook salmon, steelhead trout, coastal cutthroat trout, rainbow trout, tailed frogs and southern torrent salamanders. Officials at the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service and National Marine Fisheries Service will soon decide if Simpson's plan truly provides for recovery of the seven species on its land, all of which are either listed as "threatened" under the Endangered Species Act or candidates for such a listing. If the plan is approved, Simpson will receive permission to continue activities that might harm individual members of the species in exchange for providing conditions to benefit the overall species across Simpson's property. For example, Simpson will be able to continue clear-cutting trees near salmon-bearing streams in exchange for leaving more trees in streamside buffers, fixing old roads that erode into the streams and creating no-logging zones in headwater areas prone to landslides. While Simpson managers say their plan is a blueprint for the species to survive and thrive, many conservationists and fisheries scientists say it's not good enough. "[Simpson's plan] will likely cause a continued decline of fish populations," writes fisheries biologist Patrick Higgins in a 26-page letter to the federal agencies weighing Simpson's application. "The practices Simpson proposes [are] oriented towards timber harvest as a primary objective." Other critics include McKay's Northcoast Environmental Center, the Humboldt Watershed Council and the Pacific Coast Federation of Fishermen's Association, as well as Eugene-based Pacific Rivers Council. Natural-resource agencies like the California Department of Fish and Game (CDFG) and National Park Service have also criticized the plan, echoing many of the same concerns raised by conservation groups. "What we found across the board was that we felt things ought to be ramped up a bit," says Ken Moore, a CDFG environmental scientist charged with reviewing timber operations. "More setback in unstable areas, more trees left for woody debris recruitment [into streams to create pools], roads fixed a little bit faster." Other themes in Fish and Game's and the conservation groups' critiques: Simpson hasn't presented enough data about habitat conditions and species populations; Simpson doesn't adequately analyze the "cumulative effects" of past and future logging; and it doesn't commit to sufficient monitoring to measure whether its plan is really working. "I can't think of any plan that commits to more monitoring elements and has more data already in it," counters Simpson Resource Co. General Manager Neal Ewald. "The vast majority of fish-bearing streams [on Simpson's property] have been assessed for habitat typing." Ewald notes that the plan calls for measuring water temperatures in all streams annually. (High temperatures due to lack of pools, shallow depths and denuded stream banks can harm the species to varying degrees.) Simpson will also use a "before and after control impact" program in five watersheds to measure how logging affects habitat conditions and species' numbers. "That will allow us to test the effectiveness of our prescriptions," says Ewald. "We're [committing to] robust monitoring that will reveal when an impact potentially occurs, isolate what the impacts are and deal with it," says Ewald. The company will report on its progress publicly every two years. "The irony is that we'll have so much data to report that we don't think we can work it up every year," he says. Another complaint about the company's plan is its schedule for fixing or decommissioning old logging roads that are damaging stream habitat by eroding sediment in heavy rains. As Simpson acquired thousands of acres from companies like Louisiana-Pacific, it was also buying a legacy of bad roads built before forest-practice rules required erosion-control features. For more than five years, Simpson has worked with Redwood National Park to identify and fix eroding roads upstream of the park in Redwood Creek basin, but there are thousands of miles of logging roads on its lands that it has yet to survey and fix. The AHCP commits Simpson to spending $2.5 million annually on road-related erosion work. But the Park Service says the company needs to spend more money and work more quickly to do what needs to be done with roads. The Park Service's critique of Simpson's road plan is delivered in technical language that the agency and the company understand because they've worked together on this problem. But their arguments over whether "fixed-dollar" or "life-of-plan" costs should be used in budgeting and whether 16.7 percent or 44 percent is the right "multiplier" to account for roads not identified in geographic information systems are as impenetrable to most North Coast citizens as a family squabble over fishing rights in Micronesia. In fact, the entire discussion to date of Simpson's plan has been largely inaccessible to the public, not by anyone's design but by its complexity and bulk: 1,500 pages of technical writing in the plan itself and some 1,000 pages of comments from only about 20 groups, agencies and individuals. Information overload may be one reason why Simpson's plan has drawn little public interest since it was released more than a year ago. North Coast environmental groups are now planning their first public event on the plan, a forum in September at the Northcoast Environmental Center in Arcata. Environmentalists hope to convince the federal agencies to make Simpson rewrite the plan with additional data, tighter monitoring commitments and higher-level protection measures. The company clearly hopes to go forward with as little modification as possible, and judging by the history of habitat conservation plans, it will probably get its way. Since Congress created the habitat conservation plan program in 1982, more than 200 such plans have been approved. Simpson has two similar plans in place, one for northern spotted owls in this region and one covering more than two-dozen species on Washington's Olympic Peninsula. Pacific Lumber's conservation plan for the marbled murrelet was approved in 1999 by the Clinton administration despite hundreds of written objections and high-profile denunciations by citizens and scientists at public hearings throughout the West. (Data underlying that plan is the subject of District Attorney Paul Gallegos's fraud lawsuit against the company.) By contrast, Simpson's plan has created only a small amount of opposition, albeit from parties with great expertise and knowledge of the issues. Without an enormous public outcry, it seems unlikely that appointees of the Bush Administration would force significant additional trade-offs on the timber company. But even without stiffer legal requirements, Simpson Resource Co. will still have a strong moral imperative to make good on its commitments to protect and recover these creatures. Ewald says the company is up for the challenge. "We want more fish in these streams, more places where smolts can be sent down to the ocean," he says. "Our plan provides for recovery." IN THE NEWS | GARDEN | GOOD NEWS | EDITORIAL | CALENDAR

Comments? © Copyright 2003, North Coast Journal, Inc. |

A

blunt-spoken man who is fond of making a point with a joke, Boak

talks about how little sleep his wife Betty gets every time they

spend a half-million dollars; how readily he drives his bankers

around when they want to see their collateral at work; and how

he keeps a handkerchief in his pocket to cry in if one of the

machines wears out before its time.

A

blunt-spoken man who is fond of making a point with a joke, Boak

talks about how little sleep his wife Betty gets every time they

spend a half-million dollars; how readily he drives his bankers

around when they want to see their collateral at work; and how

he keeps a handkerchief in his pocket to cry in if one of the

machines wears out before its time. "Tractors

[dragging logs] would make roads through this ground," he

says. "[The timber industry] did tractor logging when we

didn't know better and didn't have the equipment to do better.

Now we know better and we have the equipment to do better.

"Tractors

[dragging logs] would make roads through this ground," he

says. "[The timber industry] did tractor logging when we

didn't know better and didn't have the equipment to do better.

Now we know better and we have the equipment to do better. With

fellow loggers, mill workers and local politicians, Boak opposed

the expansion of Redwood National Park. In 1977, he helped organize

a caravan of log trucks bound for Washington, D.C. Boak helped

carve the caravan's symbol -- a huge redwood peanut -- as a jibe

at President Carter, a former peanut farmer whose Interior Department

favored the park's expansion.

With

fellow loggers, mill workers and local politicians, Boak opposed

the expansion of Redwood National Park. In 1977, he helped organize

a caravan of log trucks bound for Washington, D.C. Boak helped

carve the caravan's symbol -- a huge redwood peanut -- as a jibe

at President Carter, a former peanut farmer whose Interior Department

favored the park's expansion.