July 22, 2004

IN

THE NEWS | GARDEN | PUBLISHER | THE HUM | PREVIEW | CALENDAR

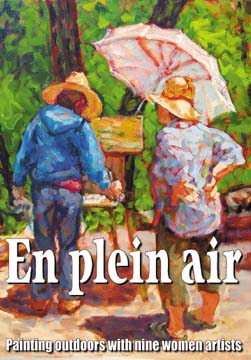

On the cover: En Plein Air,

painting in oil by Linda Mitchell

by LINDA

MITCHELL

en plein air French for "in the open air," used chiefly

to describe paintings that have been executed outdoors rather

than in the studio.

Artlex

Art Dictionary

TERRY OATS SAW THE MOUNTAIN

LION a heartbeat or two before the animal saw her. She had just

stepped back to study the painting on her portable easel when

the creature appeared around a bend in the road, heading straight

toward her on his descent to the Mad River. When he realized

she was there, the lion froze in mid-stride 30 yards away, his

eyes dark and wary. "I knew the wind was still blowing,

the birds were still chirping, but I couldn't hear any of it,

not even my own thoughts," Terry said, describing a "column

of silence" that enveloped her after the first jolt of shock.

The two remained immobile for

an indeterminate time, eyes locked, simultaneously awaiting a

first move. "The fog had settled in and time felt -- different

-- so I don't know how long it really was," she said.

![[Terry Oats at easel]](cover0722-terry.jpg) This

close encounter took place on the final day of our five-day "ladies'

plein-air painting trip," in a wild and remote region of

Humboldt County up and over Kneeland, and under the Iaqua Buttes.

Nine visual artists had come together to work directly from nature,

and on previous days of this excursion, others had been working

in the same vicinity. On this day, Terry was alone. This

close encounter took place on the final day of our five-day "ladies'

plein-air painting trip," in a wild and remote region of

Humboldt County up and over Kneeland, and under the Iaqua Buttes.

Nine visual artists had come together to work directly from nature,

and on previous days of this excursion, others had been working

in the same vicinity. On this day, Terry was alone.

Since I had been painting a

few yards away just the day before, down a rocky embankment closer

to the river, it's easy for me to picture exactly where Terry

was standing. The lion would have been slightly uphill from her,

well within pouncing distance. Her dust-coated white truck would

have been parked downhill, to her right. She was standing at

the edge of the man-made, almost vertical dirt road leading up

to the farmhouse -- and safety.

In fact, it was around the dinner

table at this very farmhouse the night before that we had all

been discussing that dreadful story about the woman in southern

California who was mauled and very nearly killed by a mountain

lion a few weeks before. "The lion had her head in his

jaws and was dragging her into the bushes..." the story

had gone, told with dramatic flair by our hostess, Liz Pierson.

Was Terry thinking about that story when her own mountain lion

later appeared? "I wasn't aware of thinking or feeling anything

until it was over," Terry remembered. "It was just

a matter of act and react. Act -- react. I was operating on pure

instinct."

The memory of something she

had recently read flittered through Terry's consciousness:

A person should never crouch down or run, but should instead

try to appear larger than the animal. She extended her arms

up and over her head. The cat bent his neck low to the ground.

"Uh-oh. Not good," she interpreted (perhaps incorrectly),

and slowly lowered her arms. The animal lifted his head. "Better,"

she decided. She waited. Finally she took a cautious step to

the side, toward the protection of the truck. The lion raised

a tentative paw and took an equally slow step backward. They

continued on, step for step. Side step, back step, side, back.

By the time Terry reached the

safety of her vehicle, her mountain lion was disappearing, backwards,

into the forest. As she scanned the woods for movement, her heart

pounding furiously, the animal poked his head out from behind

a tree, quickly tucked it back, then peeked around the other

side of the trunk. He retreated further into the forest, popped

his head up over a bush, then finally vanished for good.

Above left, Terry

Oats. [Photo by Linda Mitchell]

Below right, Terry Oats at her palette. [Photo by Carrie Grant]

Women

en plein air

![[Terry holding brushes, an dabbing paint from pallet on easel]](cover0722-brushes.jpg) It

seems completely fitting to me that Terry's wildlife encounter

happened on the final day of our painting trip. Her story provided

a grand finale for an excursion dominated by compelling, often

spine-tingling plein air stories, lived and shared around the

Pierson farmhouse dinner table each night by this group of mature

(all 50ish) professionals. Artists who work in a variety of media

with vastly different styles and methods, these women were no

strangers to direct and primal encounters with nature. It

seems completely fitting to me that Terry's wildlife encounter

happened on the final day of our painting trip. Her story provided

a grand finale for an excursion dominated by compelling, often

spine-tingling plein air stories, lived and shared around the

Pierson farmhouse dinner table each night by this group of mature

(all 50ish) professionals. Artists who work in a variety of media

with vastly different styles and methods, these women were no

strangers to direct and primal encounters with nature.

In addition to our hostess Liz,

included in the trip were Kathy O'Leary, Ingrid Nickelsen and

Judy Evenson, all oil painters like Terry Oats and myself; Carol

Stafford, a watercolorist; Carrie Grant, a photographer; Joan

Dunning, an accomplished painter as well as a published author

and illustrator of three books on nature subjects; and Becky

Evans -- recently featured in The 30,000 Salmon Project: a

Concurrence and Water/Shed, dual exhibits at Humboldt

State University's First Street Gallery in Eureka -- whose mixed

media art is more difficult to pinpoint.

"I haven't found a term

to categorize my work," said Becky, a longtime associate

professor at College of the Redwoods. "I'm not exactly a

painter or sculptor because my work entails both. Maybe you could

call me a `land' artist -- I don't know -- but my work is very

dependent on having a direct experience on site. I go out into

the land and respond to what I see and observe."

This direct experience with

nature is at the heart of creating art "en plein air."

Generally associated with the French Impressionists, the practice

of completing a painting on site (more or less) actually originated

much earlier, seen most notably in work by 18th and 19th century

English artists like John Constable and Richard Parks Bonington,

as well as painters from the French Barbizon School. The development

of more easily portable equipment, especially paint sold in collapsible

tubes, enhanced the popularity of the practice.

Plein air painting, like every

other area in the arts, has traditionally been dominated by men.

The American West, however, has a long, rich heritage of women

who have found their inspiration in nature, starting with early

Native American and Mexican artists who created extraordinary

pottery, baskets and weavings from materials found in the natural

world.

Beginning in the 19th century,

female artists with pioneering spirits, including several of

the California Impressionists, Georgia O'Keefe, and later modernists,

left more male-controlled art communities in the East to forge

new identities for themselves in the less-structured West, contributing

significantly to the cultural development of the region in the

process. I like to think the women who worked together at the

Pierson Ranch are carrying on that pioneering tradition.

It was Becky who originally

came up with the idea of a trip for women only, after she heard

of a similar event for male artists, and Terry took up the banner

and organized the excursion. The Piersons offered the Ranch and

Terry invited the artists, all personal friends of hers who enjoy

working out in nature.

A

'classic California' landscape

Thrilled to be included in a

trip with artists I've known and respected for years, I arrived

at the 110-acre Pierson Ranch on Saturday, the day before the

summer solstice, that time of year when, according to Kathy O'Leary,

"the earth is at its fullest and ready to grant wishes."

It was easy to believe. The long days, intense blue skies, and

a wild landscape described by Joan as "classic California,"

provided more than enough inspiration to fill all the canvases

I'd brought with me.

Even though it wasn't yet 9

a.m. when I got there, many of the women had already taken the

treacherous, four-wheel-drive-only road down to the river in

search of painting spots. Judy Evenson, a painter from Redway

who was eagerly awaiting word on the imminent birth of her first

grandbaby, had remained behind to paint the view surrounding

the farmhouse.

![[Liz Pierson with clippers, arbor in background]](cover0722-lizpierson.jpg) Judy's

easel was facing a multilayered landscape, all of which she was

valiantly attempting to capture on her small canvas -- lawn chairs

in the foreground, followed by Liz Pierson's sumptuous flower

garden, a golden meadow with a pond, an oak knoll, and an infinite

vista of blue mountain ranges beyond. Judy's

easel was facing a multilayered landscape, all of which she was

valiantly attempting to capture on her small canvas -- lawn chairs

in the foreground, followed by Liz Pierson's sumptuous flower

garden, a golden meadow with a pond, an oak knoll, and an infinite

vista of blue mountain ranges beyond.

Right: Liz Pierson

in her garden. [Photo by Carrie Grant]

"I don't have a focal point,

that's my problem," Judy told me when I took a peek at the

painting. She sat on a picnic bench and started drawing the scene

in pencil. "I don't know what I was thinking. I should have

sketched the composition first, but I got overeager."

I lugged my painting gear up

to the top of the oak knoll featured in Judy's landscape, and

started a painting of the 100-year-old Pierson farmhouse below,

trying, like Judy, to fit too much of the surrounding landscape

into my too-small canvas. After an hour or so, I abandoned the

painting, packed up my easel again, and headed down to the river

with Kathy and Carol Stafford, whose watercolors involved much

less gear than we oil painters carry.

Liz ferried us down the hill

in her dusty Suburban, bouncing over ruts in the road with one

hand on the wheel while cheerfully sharing news of recent bear

and rattlesnake sightings. When we reached the river, I set my

easel up in a precarious position near the water's edge and set

to work painting three canoes, working quickly in an attempt

to catch that maddeningly elusive, iridescent Pacific Northwest

light. Several other women were working along the river, each

following her own pace and inner rhythm.

Kathy and Terry, old friends

of mine from our decade together at Eureka's "C Street Studios,"

were set up nearest me, but while Terry was meticulously layering

her oils in a slow, translucent buildup of paint that would take

days to complete, Kathy was knocking out one small study after

another. Becky immediately took off her clothes and jumped in

the water. "I can't help it," she said. "I see

a river and I have to be in it." She spent the day

swimming, sketching, and "getting a feel for the place."

Joan also took some time exploring before beginning a bold river

painting downriver from us.

Ingrid Nickelsen, a wildly original

modernist who has worked on-call as a courier for Eureka's Blood

Bank for the past 30 years to make ends meet, painted upriver

all day on a river painting of her own. "I don't change

canvases throughout the day, chasing the light the way most painters

do," she said. "I like to spend all day at the same

spot, working on the same painting -- I want to get a sense

of a site in all different conditions."

Carrie Grant, a fine art landscape

photographer from Petrolia who helped form the North Coast Regional

Land Trust, was more inspired to photograph the women themselves

on this trip. "It's wonderful to see artists using nature

in a noninvasive and respectful way," she said, adding,

"I can't think of a higher or better use of the land."

In between intense periods of

work, the artists tended to wander, studying one another's paintings,

offering advice and technical information. Kathy O'Leary had

just returned from a plein air workshop in Jackson, Wyo., with

painter Scott Christensen, and shared his secret of working in

nature on small canvases with a limited palette: just Rembrandt

red medium, cadmium yellow light, ultramarine blue, two shades

of gray and a white. "In a 10-day period, I completed 29

paintings," she said. "Some were crap, of course, but

I'd say 14 to 16 were successful. They were little canvases,

but still." Kathy finished 10 paintings during her five-day

visit to the Pierson Ranch.

Most of the artists headed back

up the hill late in the afternoon, with the exception of Terry,

who stayed each day until there was no light left by which to

see her canvas. "She's completely obsessed," laughed

her old friend Joan. "I love the way, when everybody else

has already come in for the evening, she's still out there. It

makes you want to extend yourself."

![[woman with camera on tripod, woman at easel, on deck of house]](cover0722-carriejoan.jpg) ![[woman at easel, other woman watching]](cover0722-kathyjoan.jpg)

Left: Carrie Grant and Joan Dunning. [Photo by Becky Evans]

Right: Kathy O'Leary paints as Dunning looks on. [Photo by Linda

Mitchell]

Solstice

'offerings'

On Sunday evening, the solstice,

we hunted around the river bed for interesting branches, lichen,

moss and twigs, hauled them up the hill, and played around with

their arrangement until we had something that resembled an old,

yet jaunty, flat-chested woman. We posed her in a reclining position

on a big rock at the edge of Liz Pierson's vegetable garden.

"She has sort of an anti-Odalisque pose," noted Ingrid

with amusement.

This "solstice goddess"

was Kathy's idea, not surprisingly, since, as her husband, Greg,

puts it, she has an appreciation for all things "woo-woo."

"I always try to celebrate the changing of the seasons,"

she explained. When the goddess was complete, Becky suggested

setting her on fire as some sort of completion to the ritual,

an idea Liz rapidly squelched in defense of her property. We

settled for toasting our creation with Joan's homemade sangria

and retired to the farmhouse to help our hostess prepare dinner.

The white and blue-trimmed two-story

farmhouse had a timeless feeling to it, as if it might have looked

and felt exactly the same when it was built a century ago. Joan

was enchanted with the ancient wood cookstove and kept it faithfully

stoked. "I used to live on a farm," she said nostalgically.

"It's so amazing to be cooking on one of these again."

![[women picking up wood]](cover0722-goddess.jpg) ![[women sitting near assemblage of nature]](cover0722-goddess2.jpg)

Assembling the goddess. [Photos by Becky Evans]

The old, long dinner table,

set by Liz with a combination of her grandmother's linens, flea

market china and gourmet fare, made a cozy venue for extended

nights of conversation about anything and everything -- from

spirited debates about political and environmental issues to

Liz's devotion to the Blood Type Diet and Joan and Terry's

addiction to American Idol.

And then there was the storytelling,

centered on our experiences in nature and told with easy humor

by, as Joan put it, "women firmly grounded in both art and

nature." Oddly enough, at seemingly critical points, the

lights in the farmhouse kept going off, even though the electricity

was generated by solar power and the days had been long and sunny.

Frequently, the candles in the old chandelier above the table

provided our only light as the women spun their tales.

Joan told us about being sniffed

by a coyote from her toes to her nose while she slept out on

the desert floor in her sleeping bag one night; Becky described

an incident where she played tug of war with a nighttime bandit

for her purse, a thief who turned out to be a raccoon; I told

about the time a gun-toting man in camouflage cornered me at

my easel on a cliff's edge in Trinidad and remarked that he used

his gun as an tripod.

The most intriguing story by

far was Ingrid's tale about an "offering" that kept

our overly active imaginations engaged throughout the entire

trip. Several years ago, Ingrid backpacked alone into a remote

location in the Trinity Alps Wilderness and camped out on a rocky

outcropping overlooking a meadow. Twenty-five feet in front of

her was a tall snag with a hidden nest of mountain chickadees,

and she watched the parents flying back and forth each day, feeding

their chicks.

On her third or fourth day there,

Ingrid woke up sensing something was wrong. She sat up in her

sleeping bag and saw five baby chickadees next to her legs, lined

up in a perfect row from her knees to her feet. "They were

perfectly intact, not mangled, just dead. It was very curious."

Searching around, Ingrid discovered

a single bear print near where her head had been as she slept.

So had a bear lined the birds up next to Ingrid? Unbearlike behavior,

insisted Liz. The others agreed. It sounded like the behavior

of a cat, someone said, but more a domestic than a wild one.

And how had the creature, whatever it was, gotten the birds out

of that tiny hole in the tree? It was a puzzle that fueled endless

speculation, the most entertaining of which was Liz's conviction

that the offering must have been the act of a "maniac"

who had been stalking the artist for days (somehow avoiding detection

by Ingrid, a savvy tracker).

The oddest part of Ingrid's

tale, as far as I was concerned, was that she didn't immediately

pack up and hightail it back to civilization. "I found it

curious, but I wasn't frightened," she insisted. "It

seemed magical somehow -- wonderful, really."

It may have been the talk of

maniacs or dead chickadees, or possibly the lights going on and

off, but Terry decided to sleep inside the farmhouse that night

instead of outdoors like she had been. She bunked upstairs with

the other women, in a big open-beamed room with the aura of a

Girl Scout camp, complete with camp cots and flashlights. We

continued talking even after everyone had settled into their

sleeping bags, assigning imaginary merit badges.

Kathy, we decided, would definitely

receive a badge for "most paintings created"; Ingrid

would be rewarded for the "spookiest story"; Terry

was deserving of an award for "longest painting endurance"

-- but this was a few days before the mountain lion incident,

for which she'd undoubtedly earn another award for "bravery."

Terry said she doesn't see herself

as brave, even though she continued painting in the same spot

after the animal disappeared into the forest. "I think we

all have these parts of us -- hidden, primitive parts -- that

we don't have to access to except in times of extreme importance,"

she said.

Like Ingrid, Terry expressed

a feeling of wonder over her encounter with a primal force of

nature. "I could sense his intelligence. He was so perfect

-- if only you could have seen the color of his coat."

If she were to paint that coat,

Terry said she would use raw umber and a little blue. She'd pose

him as he was when they first met, with one massive paw suspended

in mid-step.

![[woman at easel on river bed]](cover0722-nicklesen.jpg)

Ingrid Nickelsen, who will be featured at Eureka's Piante Gallery

in October, paints the Mad River. [Photo by Carrie Grant]

![[Kathy O'Leary at easel on oak hillside]](cover0722-oleary.jpg) ![[O'Leary painting of oak hillskde]](cover0722-oakknoll.jpg)

Kathy O'Leary, a top-selling artist at The Gallery in Burlingame

and the Elliott Fouts Gallery in Sacramento, paints 'The Oak

Knoll,' right. [Photo by Carrie Grant]

![[Dunning painting at easel]](cover0722-dunning.jpg) ![[painting of Mad River]](cover0722-madriver.jpg)

Joan Dunning, author ande illustrator, paints with Kathy O'Leary.

[Photo by Carrie Grant]

Right: Dunning's finished painting, 'The Mad River'

![[painting of wooden chair in garden setting]](cover0722-BeyondtheGarden.jpg) ![[woman walking on rocks along river bank]](cover0722-evans.jpg)

Judy Evenson's 'Beyond the Garden.' Her work will be featured

at Eureka's Gallery Dog in August.

Right: Becky Evans explores the river. [Photo courtesy of Becky

Evans]

IN

THE NEWS | GARDEN | PUBLISHER | THE HUM | PREVIEW | CALENDAR

Comments?

© Copyright 2004, North Coast Journal,

Inc.

|