|

by HANK SIMS The Board of Supervisors' June 24 session was a grim one, even more torturous than most in this season of cutbacks, layoffs and general financial catastrophe. On the one hand, you had a whole parade's worth of uniformed firefighters, most of them representing the county's myriad volunteer fire districts. Their message to the supervisors: Unless they were given a cut of state funds earmarked for public safety, stations would be closed and volunteers turned away. The county's fire services, already a shadow of what they once were, would dwindle to unbearably low levels of protection. On the other hand, you had the county's chief administrative officer -- backed up by the sheriff, the district attorney, the public defender and the coroner -- telling the supervisors that they shouldn't give the fire districts any of the money, that they should keep it for themselves. Their departments had already been put on skeleton budgets -- any further loss of funds to the fire districts would mean that four sheriff's deputies, four correctional officers, a deputy D.A. and a deputy public defender, among others, would have to be let go. These departments simply would no longer be able to do the jobs they are mandated to do. Cops and firefighters everywhere are brothers of sorts, and the fierce intramural battle for a relatively meager portion of a relatively small source of funding that day was conducted in between the declarations of praise from sheriff to fireman, fireman to sheriff. It must have been painful for everyone concerned. The supervisors, unable to immediately avoid both Scylla and Charybdis, appointed a subcommittee to study the issue. But ever since the voters of the state of California passed Proposition 13 25 years ago, it was inevitable that this day would come. LANDMARK INITIATIVE

Proposition 13 changed government in California forever, and its influences can be found in any number of major political issues that the county has faced since. A ballot initiative to fund schools in the Southern Humboldt Unified School District with a $75 yearly parcel tax failed last month, despite the fact that 62 percent of the people in the district voted for it. Proposition 13 made it so that such initiatives had to be supported by two-thirds, instead of a simple majority, of the electorate. When the debate over bringing a Walmart to Eureka raged a few years ago, supporters of the big box weren't just arguing for rock-bottom prices: they were playing the go-go game of big retail development -- competition for sales taxes -- that has become part of the post-13 California landscape. Strangely, the 25th anniversary of Proposition 13 falls at a moment that feels very much like the moment when it was approved. Twenty-five years ago, the Humboldt County Board of Supervisors was talking about eliminating more than 100 positions in county government; this year, the supervisors are eliminating more than 200 jobs. Twenty-five years ago, too, local independent fire protection districts feared that they would soon have to put their engines up on blocks unless the county could be persuaded to part with more of its state funding. The difference is that in 1978 Californians chose the budget crisis voluntarily, and celebrated when it came. In 1977, as in every year previous, the amount of property tax a California landowner paid was based on the value of the property. Every year, assessors employed by the county would visit properties on their rolls, look at sales of similar properties, and determine whether and how much their value had risen. As the value of a home rose, the amount paid by the homeowner rose with it. That system began to break down in the mid-'70s, when the state experienced the biggest and fastest property boom in its history. In his book on Proposition 13, journalist Robert Kuttner reports that while property values in California rose 2 to 3 percent each year in the `60s, the same property in 1976 rose 2 to 3 percent in value each month. At the height of the boom, by the time an assessor got around to revaluing a house -- in most counties, this happened only every three to five years -- the value of the house may have doubled or more, and the taxes along with it. Though personal income was rising almost as fast as property values, that was little consolation to retired people, or people otherwise on a limited income. Ray Flynn, Humboldt County's assessor at the time, says that though the boom in Humboldt County wasn't as dramatic as it was in the state's urban areas, he witnessed its effect. "I had a lot of people sitting across from me crying their eyes out," Flynn says. "They said, `You're forcing me out of my home.'" A FRINGE POLITICIAN

It caught on. "Mad as hell -- that's how we felt," says Arcata's Robin Arkley, a well-known conservative commentator on KINS radio and one of the moving forces behind the drive to recall District Attorney Paul Gallegos. "Jarvis was a curmudgeon. He told it the way it was, and we thought it was great." The Jarvis-Gann initiative attacked rising property taxes in two ways. First, it would lock the tax rate at a maximum of 1 percent, unless voters approved an increase by a two-thirds majority. Average tax rates in the state were at around 3 percent, with separate levies for county, city and state governments, as well as schools and other special districts (such as fire protection districts). These agencies would have to get together and work out how that 1 percent would be shared among them. Secondly, and even more radically, it changed the way that property was assessed. Property tax is no longer based on the property's actual value, but on the price paid for it when it was bought. A house bought in 1979 for $60,000 pays a tax of $600 forever, apart from a modest yearly cost-of-living increase, until it is sold again. In addition, all assessed properties currently on the books were rolled back to what they were three years earlier, in 1975, before the boom had really gotten underway. The California Legislative Analyst's Office estimated that Proposition 13 would mean a loss of $7 billion in property tax revenues annually. Finding this unacceptable, the state's moderate forces rallied behind a measure put forth by state Sen. Peter Behr, whose district included Humboldt County. The Behr initiative, which would appear on the June 1978 ballot as Proposition 8, offered a 30 percent cut in property taxes, with greater cuts for renters and senior citizens and a "split roll" system by which commercial property would continue to be taxed at the same rate. But by the time the Behr initiative hit the ground it was too late. Jarvis-Gann supporters had already gathered over a million signatures to qualify for the ballot, a record in the California initiative process, and mad-as-hell taxpayers were sending tea bags to their representatives in the state Legislature. Voters defeated Proposition 8 while they sent Jarvis-Gann on to glory. Every city north of the Bay Area carried Proposition 13 except two: the tiny Modoc County town of Alturas -- where it was defeated by 66 votes -- and Arcata. DIVIDED COMMUNITY The Arcata City Council of 1978 did not often feel compelled, as it does today, to weigh in on matters of national and international significance every other meeting. Still, the council -- which included, in those days, Wesley Chesbro, Sam Pennisi and Alexandra Fairless (later Alexandra Stillman) -- did take an early stand against Jarvis-Gann. The backlash was enormous.

The moment was not without its irony. Seated up on the dais, all in their 20s and early 30s, were four products of a different revolt, the one that swept the country -- and especially university towns like Arcata -- in the late `60s. Six or seven years earlier it was their generation that was doing the screaming, engaging in the street politics that helped end the Vietnam War. One of Howard Jarvis' most impressive successes was to infuse middle-aged and elderly people, well-to-do patriots, with some of that same energy. Early 1978 was probably the first time that conservatism acquired a sort of hip cachet. Sitting at the table in his impeccable Queen Anne Victorian home in downtown Arcata, Robin Arkley, now an octogenarian, recalls those days with fondness. "We had all the lofty thinkers opposing us," he says, reflexively raising a fist. "We were the hard-working, taxpaying citizens, and our way of life was being threatened!" Nevertheless, the City Council's efforts to defeat Jarvis-Gann were successful, at least within the Arcata city limits. The final vote was 2,609 to 1,892 against. But the hard feelings between the town's conservatives and its liberals lived on. With Hauser's help, a renter's advocacy organization put a local initiative on the ballot in 1979 that would have required landlords to pass on their Proposition 13 savings to tenants. That was defeated. When Hauser ran successfully for state Assembly in 1982, his opponent, HSU forestry professor Jerry Partain, missed no chance to remind voters that Hauser was a pro-tax, anti-13 liberal. LOCAL GOVERNMENT HAMPERED

Flynn was wrapped up in a minor scandal when it was discovered that his department was stamping records with a skull-and-crossbones after they had been revalued. Outraged citizens thought the assessor's office was making a wry political statement, and threatened to sue Flynn for defacing public records. Flynn maintained that he needed a new stamp to mark finished reassessments, and that when he sent his assistant to the office supply store the Jolly Roger was the only stamp in stock. The lawsuit threat was dropped after the district attorney cleared Flynn of acting maliciously, but feelings still ran hot. "A couple of folks at the state chewed us out pretty good over that," he says. "We apologized and said that we hadn't meant to offend anyone, but we went on ahead using the stamp." But of all county departments, Public Works, which is charged with maintaining roads and other county infrastructure, was hit the hardest and with the most enduring cuts. The department's budget for maintenance and construction was immediately cut by 25 percent. Public Works Director Guy Kulstad had to pink-slip two of his deputy directors and shelve his plans to hire a surveyor. Eventually, the board of supervisors made the decision to let hundreds of miles of county roads, including some in the Maple Creek, Bridgeville and Petrolia areas, deteriorate from pavement into gravel. The most dramatic aftereffect of cuts to the Public Works Department came in the winter of 1992-93, when severe rainstorms left the department unable to respond to the emergencies breaking out all over the county. The 20 or so families then living in Larabee, in the Eel River Valley, were cut off from civilization for two-and-a-half weeks when the Eel River flooded and washed out their road. "We weren't the highest priority on the county's list," says Christine Rising, a Larabee resident who acted as a spokesperson for the group. "They said they were suffering from cutbacks, and that they had all kinds of other stuff that they had to deal with after the flood."

THE BAILOUT One of the issues that continually made headlines in the county newspapers in the run-up to the June 1978 election was the expected effect of Proposition 13 on Humboldt Fire Protection District No. 1, which serves a 40-square-mile area surrounding the city of Eureka. The district feared that the passage of the initiative would mean its bankruptcy. The effects of 13 were partly cushioned, though, by the $5 billion surplus the state had built up during the boom years, when everyone's taxes were still high. Seeing the deep crisis that faced local government, including special districts like Humboldt No. 1, the state engineered a bailout plan. It would take responsibility for funding the school system, thereby freeing up that portion of property taxes that went to education. The bailout gave local government some breathing room, but it created another problem, one that the proponents of 13 did not foresee. The state government assumed a greater role in California's political makeup. "Not only the funding sources, but the power over municipal government and schools basically shifted from local control to the state," says Hauser. "When the state goes through its budget problems now, it affects all the rest of us." Which is precisely what happened in 1992. Then-Governor Pete Wilson, faced with a staggering deficit and his own vows not to raise taxes unilaterally, took back much of the bailout money the state had been providing to local government, putting public schools back in to the mix of agencies funded by the local property tax. The move forced counties to establish an "Education Revenue Augmentation Fund" (ERAF), funded completely by property tax money that had belonged to local governments, and distributed to local schools. The "ERAF shift," as the move became known, again put the squeeze on local governments. Some relief came in 1993 when the voters passed Proposition 172, which instituted a statewide one-half percent sales tax earmarked to fund local public safety services. But Proposition 172 left independent fire districts out -- the funds, and the discretion to spend them, was distributed to county governments. Fire districts like Humboldt No. 1 were left in the lurch, unless they could persuade county government to cut them in. Hence the confrontation at the June 24 Board of Supervisors meeting. A MEAT CLEAVER

But Gibbs, who appeared at last month's Board of Supervisors meeting along with his colleagues from around the county, fears that the worst may be yet to come. Unless the county agrees to give independent fire districts a share of Proposition 172 funds, Humboldt No. 1 predicts that the state budget crisis may force it to close another of its two remaining stations and lay off yet more employees. Once upon a time, before Proposition 13, Humboldt No. 1 had a stable little source of revenue it could call its own. It didn't have to come on its knees to the county, or to the state, begging to be given the resources that would allow it to save people's homes, or their lives. Every year, homeowners within the district's area of protection would see on their tax bill a dollar figure, with the name of their fire department next to it. If they thought the figure was too high, they could replace the district's board of directors with people who would lower it. All that is part of the past. "I acknowledge that the proponents of Proposition 13 were reacting to an overly and increasingly heavy tax burden in California," says Gibbs. "There was an overall excess of property tax, and it was a problem. But what Prop. 13 did was take a meat cleaver to a problem that required a surgical solution."

Hanks Sims is a freelance writer living in Westhaven. IN THE NEWS | PUBLISHER | CALENDAR

Comments? © Copyright 2003, North Coast Journal, Inc. |

On

June 6, 1978, Californians marched to their polling stations

and, by a 2-to-1 margin, instituted the biggest American tax

revolt since the Boston Tea Party. As California voted, so voted

Humboldt County: 63 percent of the county endorsed Proposition

13, the "Jarvis-Gann Initiative." It was a thumping

victory for Howard Jarvis

[photo at right] , Paul Gann and

the millions of Californians who had seen their property taxes

shoot through the roof in the previous years.

On

June 6, 1978, Californians marched to their polling stations

and, by a 2-to-1 margin, instituted the biggest American tax

revolt since the Boston Tea Party. As California voted, so voted

Humboldt County: 63 percent of the county endorsed Proposition

13, the "Jarvis-Gann Initiative." It was a thumping

victory for Howard Jarvis

[photo at right] , Paul Gann and

the millions of Californians who had seen their property taxes

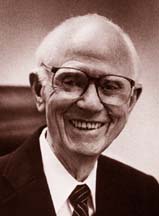

shoot through the roof in the previous years. The

time was ripe for Howard Jarvis [photo

at left] , a hitherto fringe politician

from Los Angeles. Jarvis, who had previously put forward many

similarly drastic anti-tax measures over the years, none of which

had been successful, became a media sensation in early 1978,

the public face of the outraged taxpayer. He was a short, jowly

man, 74 years of age, whose endless stock of then-heretical quips

about a fat, lazy, avaricious Big Government struck a deep chord

with California homeowners. He took as his slogan the chant of

deranged newsman Howard Beale in the 1976 movie Network:

"I'm mad as hell, and I'm not going to take it anymore!"

The

time was ripe for Howard Jarvis [photo

at left] , a hitherto fringe politician

from Los Angeles. Jarvis, who had previously put forward many

similarly drastic anti-tax measures over the years, none of which

had been successful, became a media sensation in early 1978,

the public face of the outraged taxpayer. He was a short, jowly

man, 74 years of age, whose endless stock of then-heretical quips

about a fat, lazy, avaricious Big Government struck a deep chord

with California homeowners. He took as his slogan the chant of

deranged newsman Howard Beale in the 1976 movie Network:

"I'm mad as hell, and I'm not going to take it anymore!"