|

IN THE NEWS | FROM THE PUBLISHER | CALENDAR

by GEORGE RINGWALD

photos by BOB DORAN

PORFIRIO BARROSO DIAZ IS A YOUNG MEXICAN FROM THE STATE of Oaxaca, who for the past year has played learner to my tutor under the auspices of the Humboldt Literacy Project. Nothing has so awakened me to the incredible vagaries of the English language. It is to laugh. And why isn't that spelled laff? The question arises at every one of our twice-a-week study sessions. The other day, for example, we are taking a trip through the 300 most frequently used words, according to the literacy bible called "Tutor," when we come to the word "through." It gives me a slight case of the shudders, won dering how Porfirio is going to get his tongue around that word. What's more, how's he going to take it when, after going over the assorted meanings of "through," I tell him that another word with the same pronunciation is "threw"? If he threw the book at me and said he was through, I couldn't have blamed him. dering how Porfirio is going to get his tongue around that word. What's more, how's he going to take it when, after going over the assorted meanings of "through," I tell him that another word with the same pronunciation is "threw"? If he threw the book at me and said he was through, I couldn't have blamed him.

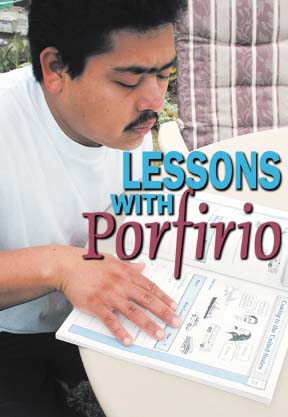

Porfirio, left, and tutor George Ringwald.

Porfirio, however, is an easy-going guy, and we have a congenial relationship. I signed on as a tutor with the express hope of getting a Spanish-speaking learner, with the thought that I might be able to learn some Spanish at the same time Porfirio was getting a hold on English. So far, he has the better hold.

One day a while back he got up to go outside the small house trailer in which he lives, saying, "I'll be back." I was impressed; hadn't heard him use the expression before. So when he returned I offered some variants on it: I'll be right back. I'll be back in a minute, in an hour or a day. Then he offered "In a year," and we both broke into laughter. Another time I was explaining the similarity at times in the meaning of "invite" and "ask." As an example, I said, "I invite you to my home." Porfirio paused only briefly before asking: "When?" He cracks me up. In another session, I asked him, "Who is your best friend?" He wasn't sure about "best?" did that mean "favorite?" Good, close enough, I told him. Then he looked up at a picture of Jesus above the door to his trailer home, and said, "He is my best friend." [See photo at below, right.] [See photo at below, right.] (Above the kitchen range is a framed sign: En nuestra casa no se fuma. Gracias. Even with my fractured Spanish, I could make out that.) Not surprisingly, Porfirio is Catholic and regularly attends St. Joseph Parish in Fortuna, where on occasion he has played on his electronic drum set, along with someone on the guitar and another on a piano. Porfirio, who has lived about four years in Eureka, comes from a family of four brothers and four sisters. One of the sisters, Guadalupe, is here in Eureka and studies English at the Eureka Adult School. And Porfirio's wife, Anna Maria, also has a tutor from the Humboldt Literacy Project. One of Porfirio's brothers, Bernardo, also lives in Eureka and goes to Eureka Adult School.  Judi Hedgpeth [photo at left], director of the Humboldt Literacy Project, notes that there are 15,000 illiterate adults (16 and over) in Humboldt County, and another 20,000 who are between 5th and 8th grade levels. Any of those 35,000, Hedgpeth says, "will have problems" -- reading prescription labels, say, so they are able to give medicine properly to themselves or their children. "They may not be able to adequately understand manuals given to them at work. So there might be safety problems involved for different companies in the area." Judi Hedgpeth [photo at left], director of the Humboldt Literacy Project, notes that there are 15,000 illiterate adults (16 and over) in Humboldt County, and another 20,000 who are between 5th and 8th grade levels. Any of those 35,000, Hedgpeth says, "will have problems" -- reading prescription labels, say, so they are able to give medicine properly to themselves or their children. "They may not be able to adequately understand manuals given to them at work. So there might be safety problems involved for different companies in the area."

Hedgpeth adds: "Fifteen thousand sounds like a lot of people -- 16 percent of the adult population. But compared to other places we're doing really well. Throughout the United States, it's more like 21 to 23 percent of the adult population." Hedgpeth, a staff of one, has been in Humboldt County since 1998, making it here from her birthplace in Berkeley with stops along the way in Reno and Los Angeles. "The first year I was here, I couldn't find a job," she recalls, "so I did bird-watching and crocheting -- much to my family's disappointment at Christmas time." She landed the literacy project post in July of 1999. She juggles running that office, in a downtown Eureka office building, with teaching two twice-weekly English classes at Sun Valley Floral Farms in Arcata. The workers, primarily Hispanic, number as many as 300 to 400 in the busier seasons. "What the company does," Hedgpeth explains, "it gives people who've been there two or more years the opportunity to take English classes that we provide. Part of it is actually paid by the company." Tutoring, Hedgpeth notes, "is quite a commitment -- not something you do once a month or so." She goes on: "We do six (tutor) training sessions a year, and get between 10 and 15 people in each training. Tutors become board members. That's a very typical routine for people to go through. We're lucky that we have an extremely hard-working board of directors. They are deeply involved and take on enormous amounts of work."

Judi Hedgpeth, standing, works with Sun Valley Floral Farms English students, from left, Adriana Morgado, Guadalupe Vega, Zenaida Abeja and Hortencia Patino.

One reason the literacy project attracts a majority of Spanish-speaking learners, Hedgpeth believes, is because it's easier to call in and say you want to speak English. "Rather," she adds, "than to come in and say, `I speak English fine. I've been through high school; I need to learn how to read.' I think there's whole lot more embarrassment with this inability to read if you grew up in this country, if you went to school here. There can also be some frustration; some of the people are downright mad. You know, they really wonder, `What the heck happened? How'd everything let this happen to me?' "I just assessed a gentleman the other day," she continues. "He had a business for about 15 years with a partner. His partner dies, and his business is gone because he didn't know how to bill, couldn't figure out what was owed to them. He was very mad about his situation and the lack of control over this life" This happened in another part of California, but the victim of this turn of events has since moved to Humboldt County to join up with a part of his family, and is now waiting for a tutor from the literacy project. Operating as a nonprofit entity since 1985, the project is funded primarily by donations -- "the money that keeps this place alive," as Hedgpeth puts it. "We get a little state money," she adds. "Last year we got $9,000. Because of California's budget problems, it's going to be less this year We're a United Way agency, so we get a little bit of money there -- a bit over $5,000 last year." As for the project's expenses, Hedgpeth mentions overhead. "We need to have an office where people can come. We need to have telephones. I need to keep records, so I need to get paper products and things like that to keep track of all you guys [tutors like me]. We need a computer, and we like to be able to buy materials new trainer books. I get a little pay. [she is the only paid employee.] You can't run much leaner than that." Recruiting teachers is no big problem. "We're still awfully small," Hedgpeth says. "Here's the staff [meaning herself], so there's a limit to how many we can handle I have a list any time of about 80 people who have called up and said they want to be tutors." The literacy project has lost some of its learner prospects in the Asian community. "We used to have a lot more when we were involved with citizenship training -- Hmong and Chinese and Thais," Hedgpeth said. But now the Hmong, once the predominant Asian group here, are reportedly leaving the area for places like Fresno and Minneapolis, in search of more job opportunities. Hedgpeth, however, is enthusiastic about setting up the first tutor training program in Hoopa this year. "So now we have a group of tutors trained and ready to go. We still need the learners to come out. We know they're there; we just need to get them to give us a call." A fellow tutor, Tommie Stanley of Eureka, tells me that her learner, Winferd Grissom, once a newspaper deliveryman for the Times-Standard, "couldn't read at all when he was 10. And now, she happily adds, "We're reading `Call of the Wild', and he's really enjoying that." Lucile Whitehurst is another fellow tutor, as well as a longtime friend from our days in Riverside, where we were fellow workers on the Press-Enterprise newspaper. "What's the hardest part of tutoring?" I ask Lucile, who has had her learner, John, for nearly two years now. "I think it's figuring out how to approach the student," she responds. (Lucile, incidentally, was a teacher at one time.) "I think in Spanish (she knows that my learner comes from Mexico) every vowel has the same sound, while in English you have a million different sounds." Japanese is similar, so while it is said to be one of the hardest languages for the foreigner to learn, at least you know that every vowel is going to have the same sound. So I commiserate with Porfirio when he has to decide how to pronounce words like "hat," "hate," "want," "water" and "after." "With all my tutoring of John," Lucile tells me, "we still have problems. He will do anything before he reads." And I wonder if it's all those convoluted vowels that turn him off. I wonder too if it's the same problem for Porfirio, when he tries to read a story in English. As my friend Lucile says, "it's like reading a foreign book." Judi Hedgpeth notes that there's "a certain percentage" of learners who don't last more than six weeks or two months. "Because, you know, this is going to take a long time. It doesn't happen overnight." Thinking of that, I figure Porfirio has come a long way. His grasp of English was virtually nil when we started out. He wasn't likely to pick up much English from his compadres in the trailer park where he lives; most are Spanish speakers, like himself. We were introduced by Theresa Whitehawk, who at the time was working with "Even Start," a program for younger children who need literacy help. Lucky for me, Whitehawk speaks Spanish, so I was able to pick up the lingo. Now I am able to address Porfirio with sentences like Que es este? (What is this?) and Este es un gato (This is a cat). Obviously, important stuff. We make a lot of use of Porfirio's Spanish-English dictionary, and my notebook is filled with words -- sombrilla for umbrella, puente for bridge, cansado for tired. And sometimes both of us are -- tired, that is. Sometimes muy cansado, very tired. In one of our earlier sessions, he said he hadn't gone to bed until 3 in the morning, and it was all he could do to keep from yawning. I thought maybe I was boring him, and that's when I suggested we knock off early -- at least one new phrase I'd given him. A stocky man with a ready smile and a good sense of humor, Porfirio had done restaurant work in Carmel for about six months before coming north to Eureka. I was used to seeing his son, William, with him when I came for our sessions, but Willie, as he is dubbed, is 4 now and goes to school in the Head Start program. He's a bright-eyed boy and is imbued with his father's sense of humor. In one of our lessons, I asked Porfirio: "What do you like about America?" He grinned, and said, "I like the ladies." Can't knock that. More seriously, he went on: "I like not much corruption. I don't see the police taking money. In Mexico there is much corruption." And how about racismo?I ask. He mentions that he has a very good friend, an Anglo he knows at work, and he's no racista. And he helps him with his English. "Hey, man, get out of my way," for example, and "What's up this morning, man?" Through it all, Porfirio maintains his wit, his sense of humor. One day we were talking, for some reason, about the great tenors of the Metropolitan Opera, and of course the name of Placido Domingo came up. Porfirio smiled and said, "Placido Sunday." We both laughed -- "Domingo" is "Sunday" in Spanish. And now on to more reading. "Shoot for the moon!" I say, and let's start with War and Peace. In 1968, as a reporter for the Riverside Press-Enterprise, George Ringwald won a Pulitzer Prize for Public Service.

In a series of investigative pieces, Ringwald documented abuses by the judicial system in its management

of properties belonging to the Agua Caliente Indian tribe near Palm Springs.

IN THE NEWS | FROM THE PUBLISHER | CALENDAR Comments? E-mail the Journal: [email protected]

© Copyright 2002, North Coast Journal, Inc. |