July 1, 2004

IN

THE NEWS | ART BEAT | THE HUM | PUBLISHER | CALENDAR

![The Return of Indian Island - Restoring the center of the Wiyot world [Wiyots in dugout canoes in bay]](cover0701-photohed.jpg)

Tribal members in dugout canoes

make their way from Indian Island to the Adorni Center

for a ceremony marking the return of part of the island to the

Wiyots. Photo by Ryan Palmer.

by BOB DORAN and GREGG McVICAR

![[Cheryl Seidner smiling, line of Wiyot men behind her, and bay in background]](cover0701-Seidnerarriving.jpg) FRIDAY, JUNE 25. IT

WAS A BEAUTIFUL DAY, a great day. The sun glistened on Humboldt

Bay as two traditional redwood dugout canoes rounded the end

of Woodley Island on a historic journey that began on Wiyot land

on Indian Island. FRIDAY, JUNE 25. IT

WAS A BEAUTIFUL DAY, a great day. The sun glistened on Humboldt

Bay as two traditional redwood dugout canoes rounded the end

of Woodley Island on a historic journey that began on Wiyot land

on Indian Island.

Among the passengers: Cheryl

Seidner, 54, tribal chair of the Table Bluff Wiyot Reservation.

Their destination: the Adorni Center, where Seidner and Eureka

Mayor Peter La Vallee would sign papers making official the return

of 40 acres of land on Indian Island from the city to the Wiyot

people.

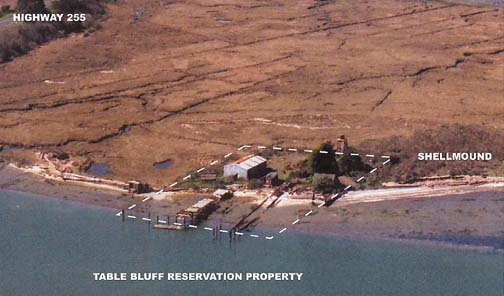

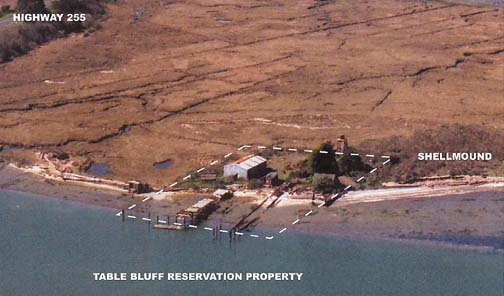

The process was set in motion

earlier this year on May 18, when the City Council voted unanimously

to approve the transfer. The 40-acre gift consolidates the tribe's

ownership of the portion of the island north of the Highway 255

bridge between Eureka and Samoa, land considered sacred by the

tribe. The Table Bluff Wiyots already own 1.5 acres there, land

that had been used as a ship repair facility from around 1870

until the 1980s.

After purchasing the parcel

in 2000, the tribe began cleaning up the remnants of old ships,

paints and other trash and toxic material on the land, while

drawing up plans for the restoration of an area they call Tuluwat

Village.

Photo above: From

left: Cheryl Seidner, Chris Peters, Julian Lang, Frank Tuttle

and Thomas Wilkinson

< <

- > >

![[McGinnis family posing for photo]](cover0701-McGinnis.jpg) Joe

McGinnis, a Wiyot from the Bear Creek branch of the tribe, was

among those waiting for the boats to arrive. "This is a

great day for all our people," he said, emphasizing the

importance of the plan to rebuild the dance house on the island

and bring the Wiyots back into the circle of North Coast Indian

dancers. Joe

McGinnis, a Wiyot from the Bear Creek branch of the tribe, was

among those waiting for the boats to arrive. "This is a

great day for all our people," he said, emphasizing the

importance of the plan to rebuild the dance house on the island

and bring the Wiyots back into the circle of North Coast Indian

dancers.

"The dances are important

for healing," he continued. "Everything has a purpose.

You dance for the world, not just for your family or your people.

You dance to renew the world."

His wife, Nicole, a member of

the Hupa Tribe, was inside the Adorni helping their daughter,

Tea, don her traditional regalia, a basket cap and a white buckskin

outfit adorned with shells that turned her skirt into a musical

instrument when she walked. Tea would stand in a receiving line

welcoming Seidner and her entourage along with five other girls

from the Yurok and Karuk tribes, a show of unity.

"Unity is what is going

to bring our salvation, as people, as the world," said McGinnis,

"so yes, this is a great accomplishment, not only for Table

Bluff, but for all Wiyot people, all Native Americans in the

area and elsewhere, for people everywhere. The more people involved,

the better it can be. Sharing this is great, having other people

come out, non-Native people too. It's a proud day, a great day,

for all of us."

Above left: Joe

and Nicole McGinnis and their daughter, Tea.

< <

- > >

Two weeks before the transfer

papers were signed, Journal staff writer Bob Doran and

his friend Gregg McVicar sat down with Cheryl Seidner for an

extensive interview.

McVicar, a Bay Area Native American

radio producer with Tlingit heritage, is the host of a nationally

syndicated program on Native American music called "Earthsongs."

He is also a producer for "Bay Native Circle," a weekly

program on Berkeley's Pacifica station, KPFA-FM. Portions of

the following interview aired on that program last Wednesday.

NCJ:

You have some really great news about your relationship with

the city of Eureka. Could you tell us the story?

Seidner: We were successful in getting back 40 acres of

275 acres of Indian Island, which is our sacred site. The city

of Eureka owned 90 percent of the island, 10 percent [was] in

private ownership. We purchased 1.5 acres at $106,000 in the

year 2000.

For about two and a half years

we have been working with the city of Eureka trying to get back

more acreage. [We came to an agreement with the city] on May

18, 2004 to [acquire] 40 acres of the island, the section [north

of] where the bridge goes across [the island].

NCJ:

That's quite an enhancement to your holdings.

Seidner: It is. The 1.5 acres that we purchased was the

Tuluwat Village site, [but] the city still owned the burial grounds

and also the shell midden. We decided that we wanted to have

that, and have the opportunity to take care of it, since it has

been in disrepair for decades.

NCJ:

Could you explain what a shell midden is?

Seidner: Over thousands of years people have been going

back to the same place. This is where they put their shells,

and it built [up] the area. [Note: Clams, mussels and other shellfish

were always an important part of the Wiyot diet.] So the shell

midden on the island is thousands of years old. After the 1860

massacre, this is where a lot of our people were buried.

And it was not the only massacre

that took place on that day. There was one on Piedmont, which

is the south spit, and one at the mouth of the Eel River.

![[Jerry James]](cover0701-jerryjames.jpg) We

do not know how many people were killed totally, but they say

between 60 and 100 people were massacred on the island that night.

There was only an infant found [alive] the next morning, under

his mother, and an old woman, "shiroke," [Wiyot for

old woman] who got herself quagmired in the mud, singing a mourning

song, mourning the people who were killed that night; and [there

were] two young adolescents, teenagers, and one toddler [found

alive]. The baby that was found was my great-grandfather [Jerry

James, photo at right]. We

do not know how many people were killed totally, but they say

between 60 and 100 people were massacred on the island that night.

There was only an infant found [alive] the next morning, under

his mother, and an old woman, "shiroke," [Wiyot for

old woman] who got herself quagmired in the mud, singing a mourning

song, mourning the people who were killed that night; and [there

were] two young adolescents, teenagers, and one toddler [found

alive]. The baby that was found was my great-grandfather [Jerry

James, photo at right].

NCJ:

It's almost mythic, it's so terrible. And the perpetrators of

this crime?

Seidner: There were five or six white settlers from the

Eureka area; they just decided they no longer wanted the Indian

people. [Robert] Gunther had bought the island from a gentleman

named Moore [Captain John Moore]. We don't know how Moore acquired

the island, maybe by the United States giving it to him or something.

Moore sold it to Gunther and [the massacre was] three days after

[that purchase]. I'm not saying that Gunther had anything to

do with it, but three days after, the slaughter took place.

![[aerial photo of Indian Island]](cover0701-indianisaerial.jpg)

ABOVE: Aerial photo of Indian

Island looking south

BELOW: Indian Island looking toward village site

![[view of Indian Island from water]](cover0701-indianislandpan.jpg)

Reviving

a culture, completing a circle

NCJ:

Tell us more about the cultural and spiritual significance of

the village.

Seidner: It's not the village -- it's the island. The island

is cultural; it is the center of our world. This is where we

come for some of the major dances. We are a part of what they

call the five high tribes of dancers with the Jump Dance. We

are part of that with the Hupas and the Yuroks, the Karuks, and

the Tolowas. The Wiyot makes the circle. Chilula is another

tribe -- they are no longer considered a tribe because there's

no one left, but I know there are descendents of the tribe, and

they have been dancing all these many years as Chilula. The Wiyot

have never danced since 1860. They tell us the circle is broken

-- and once we dance, the circle will be complete. And when we

dance it will be with all the other tribes coming together. So

the island is sacred not for its village site, not [because of]

the massacre -- but because this is the center of our world.

NCJ:

What's going on with the Wiyot people today?

Seidner: We have 477 tribal members. We have them all over

the world: in Germany in Iowa, Idaho, Oregon, Washington, Arizona,

Nevada, all through California, all over he place. The main concentration

is local. We have 35 houses on the reservation and over 100 people.

A lot of the families are not all Wiyot, because people marry

outside of their tribe and some children are on different [tribal]

rolls.

Our offices are located at Table

Bluff Reservation and we employ about 20 people. We continue

to work on what keeps us alive and going today. Part of our hope

with the partial return of the island is that we can start concentrating

on [the] cultural perspective.

After the massacre, the language

was gone. No one [spoke] it again. Our basketweavers left...

NCJ:

Why did they stop speaking the language?

Seidner: When people kill you, you just don't teach it

anymore. The white people are here to stay. They are not going

home. They now consider this home, and at that time [in the past,

being Indian] was dangerous. You learn to fit in. This is what

my grandfather would say. Though the government wanted us to

assimilate, and that's what they tried to do, my grandfather

said, `You have to work with all people all of the time.' Part

of that [means] when you get beat up for speaking your language,

you start speaking English.

Our basketweavers are gone.

Our dreamers are gone. And our wisdom is gone. A lot of things

have left. So culturally, we are -- sad.

A 14-year-old child told me,

`Why even bother with culture, `cause the culture is dead.' It's

really hard when you're confronted [in that way]. What do you

say? It really kind of rocked me for a moment, but I told her,

`It's choices; choices you make. At least you have a choice.'

I choose to try to learn my

language. I choose to try to look at the positive things in our

culture -- at what it will bring us. I think it behooves us to

learn more about it so that we can have a cultural identity.

We were lucky in my family because my parents always talked to

us about our culture, what we do, when we do it, why do it that

way. But there are some kids who weren't brought up that way,

and so I see culture as a very important part; language is a

very important part. So I make a choice. That's what I told this

young girl -- it's a choice -- and I choose to go and seek my

culture and my language. And she has that choice as well.

NCJ:

Will you bring back the dancing?

Seidner: Yes. We hope so. We will try our darndest.

NCJ:

How do you plan to go about it?

Seidner: Since we are kin to the Yurok Tribe and we have

dances similar to the Hupas and the Karuks, we will glean some

information from them. And we will work with what little we know

ourselves and see what we come up with. Every culture evolves.

No culture is stagnant. So we evolve, just like any culture and

other any peoples. New things come in and we take what's good

out of the new stuff and go on.

![[Wiyot girls in shell and bead decorated dresses and hats]](cover0701-WiyotGirls.jpg)

Girls dressed in traditional

regalia, from left to right: Loreta Brown (Wiyot, Yurok, Pitt

River, Paiute), Michelle Hernandez (Wiyot), Tyithreeha Allen

(Yurok, Karuk), Ruby Tuttle (Yurok, Karuk, Maidu, Wylaki), Tea

McGinnis (Wiyot, Hupa, Yurok).

Resilience

NCJ:

You've alluded to some things that were very painful for your

people. I was looking at your Web site, www.wiyot.com, and there

was a line that caught my eye. It says, "Pre 1850, there

were approximately 1,500 to 2,000 Wiyot people living within

this area. After 1860 there were an estimated population of 200

people left. By 1910 there was an estimate of less than 100 full

blood Wiyot people living within Wiyot territory. This rapid

decline in population was due to disease, slavery, target practice,

`protection,' and being herded from place to place, and of course,

massacres."

Slavery? Target practice?

Seidner: Indentured slavery. What that means is you'd have

to work for a family or an individual until your debt was paid

off. But [even some] who didn't have debt were enslaved.

We owned all of this land from

Little River to Bear River, out to Chalk Mountain and to Berry

Summit. And there were approximately 2,000 people, and

[50 years after the massacre] there were only about 100 full-bloods

left. I am one of the last of the three-quarter bloods. We continue

to survive. They tried to bump us off, but we came back.

As my great-uncle told me one

time, `I used to be a prizefighter' -- he was a little man, but

he was a winning boxer in his [weight] class -- he said, `They'd

knock me down on my butt, but I would get up again and I'd go

another round. I'd get knocked down and I'd get up again.'

I look at him and say, `That's

the Wiyot Tribe.' We've [been] knocked to our knees, we'll get

up and we will continue. I believe in 1958-'59 when the Termination

Act went by we were knocked to our knees. We were considered

non-Indians. Our title [according to] the federal government

was non-Indian Indians. (She laughs loudly.) It always confused

me when I was growing up. We got back up. And we fought a great

fight with the federal government.

You know my predecessor [Albert

James] did a great job. We got our federal recognition back as

a tribe in 1990, but as individuals, it was in '76. I remember

that because in March 1976, my mother got a letter in the mail

saying she had become a Native American or American Indian. She

said, `Oh look at this, I'm going to die an Indian.' We did not

know that she had cancer, and she did pass away three months

later.

[After the massacre, the U.S.

government] decided they were going to take care of us and watch

over us so nothing happened to us. That's why they took us to

the stockades up at Fort Humboldt in the dead of winter. And

that's why our children died of exposure, our old people died

of pneumonia, our women were raped and murdered. That's how well

the U.S. government took care of us.

The next thing was, we had three

trails of tears: We were herded up to Smith River, then over

to Hoopa, then down to Round Valley. We had three marches, and

each one brought fatalities. We just look at that and say, `We

survived that.' We continue to survive all these horrendous things.

And you see that, not just with the Wiyot people, you see it

across the United States, you see it in other nations across

the world.

We as Wiyot people do not have

economic development; we do not have a forest; we do not have

a river running through our reservation. We have one lone pine

tree on our reservation. The money we got for the 1.5 acres on

the island [came from a fund-raising] campaign. We just continue

to go forward.

So in 1970 we started a campaign

to get our federal recognition back, suing the federal government.

In 1980 we went in earnest and filed our lawsuit. In 1990 we

got our recognition back from our termination in 1958-'59.

[Note: The Rancheria Termination

Act, enacted in 1958, provided for the transfer of title of all

rancheria land and assets from the U.S. government to Indian

tribes for distribution to individual families. It also ended

special rights granted to Native people as members of tribes.]

So again, we [have been] knocked

to our knees and made to bow, but we have that survivor spirit.

We get back up. And we're still standing.

![[shore of island showing shellmounds]](cover0701-shellmound.jpg)

ABOVE: View of oyster shell midden looking north on the island.

(photo by Mike Wilson, courtesy of Humboldt Water Resources,

Engineering and Science)

![[plastic covering shell mounds from erosion]](cover0701-erosioncontrol.jpg)

Erosion control over shellmounds.

(photo by Mike Wilson, courtesy of Humboldt Water Resources,

Engineering and Science)

Looking

toward the future

NCJ:

I'm going to ask this because I'm sure it's on many people's

minds. Are you going to put a casino on the island some day?

Seidner: I'm going to slap you upside the macoats

[the head]. (Laughing) If someone asks me that one more time

I'm going to go screaming mad.

No! Keyow, keyow (no)!

Would you, if you were a devout

Catholic or a devout Muslim, would you go to the center of your

world and put a casino on there? This is the center of our world.

This is where we hold the dances that make us whole, that make

us be better people and put the world right, and to begin anew

each year. To have a casino on the island would be horrific.

NCJ:

You got the 40 acres on the island supposedly for free, but I'll

bet you spent a great deal of money to get there.

Seidner: We got grant money [to help work out the details].

But we did get the land for free. The city of Eureka did not

ask for payment for the property, not even a dollar. We spent

funds on getting this far, but it's nothing in comparison [to

what it is worth to us].

NCJ:

Isn't there a lot of work to do in terms of cleaning up the site?

What used to be there?

Seidner: It was a boat basin. Boats were made there at

one time. We've been working on it since 2000, cleaning it up.

We just took off 33 tons of scrap metal. We almost sunk the barge.

![[people moving scrap metal, oil cans and trash from island site]](cover0701-cleanup.jpg)

RIGHT: Volunteer cleanup crew (photo by Leona Wilkinson)

NCJ:

Is there a problem with leftover toxic materials?

Seidner: Fortunately it's minimal. We've been doing toxic

cleanup for two years, [on] hot spots, and it hasn't been [as

bad as] we thought it was going to be, so we're very, very happy.

We've had private donors come in [to help pay for it]. We're

working on another waste cleanup currently and it's not costing

[as much as we thought it might].

We're continuing to take out

[vegetation] that does not belong there. We're trying to recoup

it to the way it may have been pre-contact, [although] nobody

knows exactly what it looked like.

We're working towards putting

a dance house on the island. The dance house itself will cost

between $200,000 and $300,000, and that's [just one part of a

larger project] which could cost $2 million. These things are

for not houses or anything [like that] it's for cleanup [and

restoration].

We purchased the 1.5 acres,

and we've asked for the 40 acres as an educational project and

we're including Humboldt State University, College of the Redwoods

and Humboldt County Schools to participate. So it's not just

for us; we are thinking about everybody.

NCJ:

I imagine it will also be an attraction for travelers going up

and down Highway 101.

Seidner: Possibly. But it will not be a tourist place.

When it's available, we will let people know when we're going

to be there. We will have the final say as to who gets on the

island. And when we're using it for our own private use, it will

be just for us.

![[map of Indian Island plans, showing site with outlines delinating planned dance house, caretaker's residence, kitchen, toilet, storage, fire ring, dock and bulkhead/sculpture, along with existing shellmound, salt marsh and shore]](cover0701-planmap.jpg)

Site illustration courtesy Humboldt Water Resources, Engineering

and Science

NCJ:

What about the rest of the island, the other 230 acres?

Seidner: The city still owns the major portion of the island,

and I have already let them know that we want it. Whatever they

have, we would like to have. That may come in five years or so.

You know we're not in any major rush. We want to do a good job

with the 40 acres. We want to make that the place we can come

home to and be a part of.

I look at the 10 percent that

is in private ownership [former Eureka mayor Nancy Flemming's

home], and I would like that part as well. But I know, our tribe

knows, how it feels to be herded here and there and not to be

wanted anywhere, and the longing to come home. And we would love

to have our neighbors be there as long as they would like to

be there, but [we would be happy] if they would like to sell

to us or give it to us.

I understand why they want to

be there, and our tribe has no [intention] to harass anyone.

We know what that feels like. We know how it feels not to be

wanted; we know how it feels to be taken away from our land.

We know how it feels to be called names. But that's not what

we're about -- we are about trying to work well with our neighbors

and to be a user-friendly tribe.

NCJ:

I can tell from the look that comes across your face when you

describe it, this glow, that this is a very emotional time for

everyone. It seems from the reports that the City Council was

almost as overwhelmed. What do you see as the historic significance

of this?

Seidner: As I have been told, this has not happened in

any city in the state of California, and I'm hearing that this

might be something really new across the nation. I don't know.

I can't tell you that for sure. Somebody asked me, `When did

you start working toward getting the island back?' I said, `The

day after the massacre: Feb. 27, 1860. That's when we started.'

It may not have come around

to everybody's mind easily, but I think it's in our DNA to have

it back. That's where we belong; that's where our dances belong.

When we have people who think we have no culture -- I want to

give them the opportunity to seek that out for themselves. It

is pretty important.

When they made the motion, Chris

Kerrigan, who is the youngest member of the City [Council] gave

a very emotional speech. I did not know how emotional people

were. I was really stunned. My sister [Leona Wilkenson] and I

showed almost no emotion when it was all going on; we just sat

there and listened. He made the motion; Mary Beth Wolford seconded

the motion. Everyone was tight in the throat, on the verge of

tears.

She said, `We're all very, very

honored. This is long overdue.'

There's a time for everything.

It may not have been time 30 years ago nor 100 years ago. The

time was right: May 18, 2004. That was our time, I believe.

![[mayor Le Valley and Cheryl Seidner signing papers]](cover0701-signing.jpg)

ABOVE: Eureka Mayor Peter

La Vallee and Table Bluff Wiyot Tribal Chairwoman Cheryl Seidner

sign the papers transferring 40 acres of Indian Island to the

tribe; city council members Jeff Leonard, Mary Beth Wolford and

Virginia Bass-Jackson look on.

![[Cheryl holding gift from mayor]](cover0701-giftexchange.jpg)

ABOVE : La Vallee presents

Seidner with a symbolic clay pot filled with earth from the island.

![[Mayor receiving jar of salmon from Seidner]](cover0701-giftexchange2.jpg)

ABOVE : Seidner gives La Valle

a jar of smoked salmon, one of several gifts, including shell

necklaces and medicine bags, given to each city council member.

|

For more information on the Tuluwat

Village Wiyot Sacred Site Fund and the Indian Island Cultural

and Environmental Restoration Project, go to www.wiyot.com.

Gregg McVicar's radio show "Earthsongs"

can be heard on KHSU-FM Sunday

nights at 3 a.m. (Feel free to call the KHSU Listener Comment

Line at (707) 826-6089 to ask the hear the show at a more reasonable

time.)

For more on "Earthsongs"

and "Bay Native Circle," including a link to listen

online, go to www.radiocamp.com.

The Bay Native Circle show featuring Cheryl Seidner is dated

06-23-2004.

|

IN

THE NEWS | ART BEAT | THE HUM | PUBLISHER | CALENDAR

Comments?

© Copyright 2004, North Coast Journal,

Inc.

|

![The Return of Indian Island - Restoring the center of the Wiyot world [Wiyots in dugout canoes in bay]](cover0701-photohed.jpg)

![[Cheryl Seidner smiling, line of Wiyot men behind her, and bay in background]](cover0701-Seidnerarriving.jpg) FRIDAY, JUNE 25. IT

WAS A BEAUTIFUL DAY, a great day. The sun glistened on Humboldt

Bay as two traditional redwood dugout canoes rounded the end

of Woodley Island on a historic journey that began on Wiyot land

on Indian Island.

FRIDAY, JUNE 25. IT

WAS A BEAUTIFUL DAY, a great day. The sun glistened on Humboldt

Bay as two traditional redwood dugout canoes rounded the end

of Woodley Island on a historic journey that began on Wiyot land

on Indian Island.![[McGinnis family posing for photo]](cover0701-McGinnis.jpg) Joe

McGinnis, a Wiyot from the Bear Creek branch of the tribe, was

among those waiting for the boats to arrive. "This is a

great day for all our people," he said, emphasizing the

importance of the plan to rebuild the dance house on the island

and bring the Wiyots back into the circle of North Coast Indian

dancers.

Joe

McGinnis, a Wiyot from the Bear Creek branch of the tribe, was

among those waiting for the boats to arrive. "This is a

great day for all our people," he said, emphasizing the

importance of the plan to rebuild the dance house on the island

and bring the Wiyots back into the circle of North Coast Indian

dancers.![[Jerry James]](cover0701-jerryjames.jpg) We

do not know how many people were killed totally, but they say

between 60 and 100 people were massacred on the island that night.

There was only an infant found [alive] the next morning, under

his mother, and an old woman, "shiroke," [Wiyot for

old woman] who got herself quagmired in the mud, singing a mourning

song, mourning the people who were killed that night; and [there

were] two young adolescents, teenagers, and one toddler [found

alive]. The baby that was found was my great-grandfather [Jerry

James, photo at right].

We

do not know how many people were killed totally, but they say

between 60 and 100 people were massacred on the island that night.

There was only an infant found [alive] the next morning, under

his mother, and an old woman, "shiroke," [Wiyot for

old woman] who got herself quagmired in the mud, singing a mourning

song, mourning the people who were killed that night; and [there

were] two young adolescents, teenagers, and one toddler [found

alive]. The baby that was found was my great-grandfather [Jerry

James, photo at right].![[aerial photo of Indian Island]](cover0701-indianisaerial.jpg)

![[view of Indian Island from water]](cover0701-indianislandpan.jpg)

![[Wiyot girls in shell and bead decorated dresses and hats]](cover0701-WiyotGirls.jpg)

![[shore of island showing shellmounds]](cover0701-shellmound.jpg)

![[plastic covering shell mounds from erosion]](cover0701-erosioncontrol.jpg)

![[people moving scrap metal, oil cans and trash from island site]](cover0701-cleanup.jpg)

![[map of Indian Island plans, showing site with outlines delinating planned dance house, caretaker's residence, kitchen, toilet, storage, fire ring, dock and bulkhead/sculpture, along with existing shellmound, salt marsh and shore]](cover0701-planmap.jpg)

![[mayor Le Valley and Cheryl Seidner signing papers]](cover0701-signing.jpg)

![[Cheryl holding gift from mayor]](cover0701-giftexchange.jpg)

![[Mayor receiving jar of salmon from Seidner]](cover0701-giftexchange2.jpg)