|

|

|

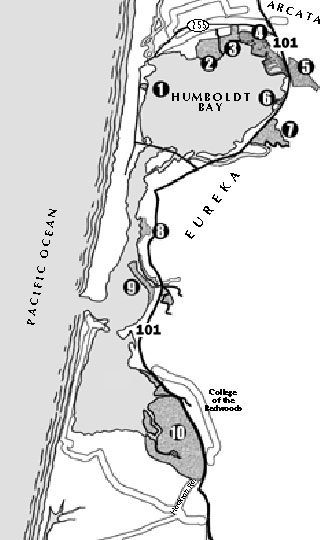

1MANILA COMMUNITY

PARK 2MAD RIVER SLOUGH WILDLIFE AREA 3MCDANIEL SLOUGH 4ARCATA MARSH & WILDLIFE SANCTUARY 5BAYVIEW RANCH 6BRACUT MARSH 7FAY SLOUGH WILDLIFE AREA 8EUREKA MARSH 9ELK RIVER WILDLIFE AREA 10HUMBOLDT BAY WILDLIFE REFUGE |

Turning the tide

That said, there is a real effort to

restore a significant portion of the wetlands to a functional -- if not

historical -- state. There are at least 11 different governmental entities

involved in wetlands restoration on Humboldt Bay right now, spanning municipal,

county, state and national levels. The cities of Arcata and Eureka both

own wetlands, as does the state Department of Fish and Game, the U.S. Fish

and Wildlife Service and the Manila Community Services District. Funds are

supplied for restoration by the Coastal Conservancy and regulations governing

their use and conservation are issued by a host of different agencies.

There is a great deal of diversity among these projects. Varying levels of funding and differing visions of what a wetland should be have resulted in a wide spectrum of wetlands on the bay.

The Arcata marsh, for example, doubles as a sewage treatment facility and salmon ranch. Williams called the facility "world class. Pilgrims come from all over to see it in action," Williams said.

The community support of the idea of sustainable management has been the foundation on which the project's success has been built, he added.

There have been problems, of course. Conflicts over unruly dogs in the marsh have led to a call for a ban on the canines, and transients often use the land as a campground.

But the project is definitely well-known, well-used, and widely recognized as a success. It won an award for Innovations in Government from the Ford Foundation and Harvard's Kennedy School of Government in 1987.

Eureka's "Palco" marsh, on the other hand, is almost unknown. Located at the foot of Del Norte Street, this 80-acre plot was acquired from Pacific Lumber by the city as part of the Bayshore Mall development transaction. Lacking adequate funding -- or even a sign -- the marsh has languished for years, unrecognized and unappreciated by most of Eureka's citizens. The one group utilizing it regularly were the homeless, who often camped there.

"It created a habitat for certain individuals that maybe didn't have the best interests of others at hand," said Joel Canzoneri, administrative analyst for Eureka's Community Services department. The city has recently cleaned up brush that had provided these individuals privacy, and the marsh now presents a beautiful view of the Bay -- one which you're likely to have all to yourself, since few even know it is there.

"We haven't tooted our horn as much as Arcata," said Canzoneri.

Then there is the Coastal Conservancy's ill-fated Bracut marsh. The six-acre plot on Highway 101 adjacent to the Bracut industrial park is an experiment in environmental mitigation that has floundered since its inception.

![[photo of PALCO marsh]](cover0622-palcomarsh.jpeg) Eureka's PALCO marsh is located at the

Eureka's PALCO marsh is located at the

foot of Del Norte Street.

California has a "no net loss" policy on wetlands, meaning that if you fill in wetlands for any purpose, you have to create or restore wetlands elsewhere to compensate. Starting in the early 1980s, a series of small, isolated wetlands in Eureka with limited habitat value were filled to allow for development. The parties filling them paid the Coastal Conservancy to restore the Bracut Marsh. The theory was that one could replace all of the wetlands they had filled with wetlands of higher quality elsewhere. The idea of a mitigation bank like Bracut was to provide additional flexibility to developers while increasing the total environmental value of the wetlands.

What sounded great in theory ended up being a nightmare in execution: Woody debris left in the site had changed its soil chemistry, and the water allowed into the marsh did not bring in enough sediment. The result, according to a 1992 Army Corps of Engineers report, was "poor marsh habitat."

To compound the problem, there was no money for effective monitoring of the site. And to top it off, a bacteria decomposing the woody debris left in the site emitted a gas that made it smell like rotten eggs.

Efforts have since been made to try to make the project work, and the site does now support certain rare plants and shorebirds. But the tidal flushing that should have cleared out the woody debris has been insufficient -- and the aroma of rotten eggs still wafts in the air.

Integrated approach needed

One of the most important efforts in

wetlands restoration currently underway will take place mostly on paper.

In order to guide wetlands restoration, scientists need to know just what

has already been accomplished by existing projects and what potentially

could be done -- and that information has never been collected into a single

whole.

The diverse mix of agencies, restoration philosophies and levels of community involvement make getting a comprehensive view of what's happening around the bay as a whole difficult, said Mark Wheetley, North Coast projects manager for the Coastal Conservancy.

"If you're looking at the 48 miles of Humboldt Bay shoreline, about 75 percent of it is in public ownership. And every one of those government entities has undertaken some level of restoration on some projects."

Mark Andre, Arcata's deputy environmental services director, said he thinks there was a need for a big-picture integrated approach for the rejuvenation of the Humboldt wetlands.

"If you get one, let us know," he said with a laugh.

One may indeed be on the way. Wheetley said that he is leading an effort to get funding for a comprehensive wetlands management plan. Such a plan will be important to future restoration efforts because it will identify the benefits and the costs of any particular project in relation to other prospective restorations, and "tell us what the opportunities are."

It would also help to answer some critical questions facing wetlands restoration on Humboldt Bay, such as: What is the proper balance of wetlands and agricultural lands on the bay? Which projects should receive highest priority? What is the status of threatened species on the bay?

"That," said Wheetley, "is what we are going to be finding out in this study."

Arcata's next step

The City of Arcata has already established

itself as a friend of wetlands. Its marsh and sewage treatment project is

a standard by which sustainable development projects are measured. But rather

than rest on its laurels, the city is gathering steam for its next step

in wetlands restoration.

The property in question, a 240-acre plot on the McDaniel Slough jointly owned with the California Department of Fish and Game, is adjacent to the 166-acre Arcata Marsh and Wildlife Sanctuary. The land is already in a wetland state, but insufficient tidal flushing limits its habitat value and the native pickleweed is being forced out by Chilean cordgrass.

A restored pickleweed marsh with proper flushing through tidal channels could have many advantages, including recreation opportunities, habitat for rare plants and animals, and even possibly a reduced mosquito population. One of the most exciting opportunities that it offers is the potential to open up a new front in the fight to save the salmon fisheries.

"We're starting to find out how important these tidal marsh channels are for salmonids," Williams said. "When you eliminate tidal marshes, you eliminate all these tidal channels and that means that migrating salmon have nowhere to hang out, feed, acclimatize before they head out into the ocean. They may not yet be sufficient size to survive.

"When there are tidal marshes available, they do utilize those marshes, gain body weight, become larger fish and when they head out they survive better.

"Everybody has been looking upstream and saying we have to restore spawning grounds. Because this tidal marsh landscape has not been there, people have not understood the importance of it. Now we're starting to recognize that."

![[photo of McDaniel Slough]](cover0622-mcdslough.jpeg) McDaniel Slough northwest of Arcata.

McDaniel Slough northwest of Arcata.

And the McDaniel Slough project isn't all that's happening in Arcata. Negotiations are underway to acquire a 300-acre plot called the Bayview Ranch for restoration. The plot, currently owned by George Schmidbauer, owner of Schmidbauer Lumber, would be the largest single acquisition and restoration yet undertaken by the city. Andre said that he could not comment on the negotiations because they were confidential, but said that the success of the purchase and restoration will be contingent on the community showing the same involvement it has for the city's other marshes.

"Anytime you have that large of an acquisition it is certainly imperative to get the community involved," he said. He pointed out that "in Arcata we rely a lot on volunteers for maintenance and providing docent services."

But even if Arcata were to hire replacements for its volunteers, the community would still be an essential ingredient in healthy wetlands. Andre pointed out that high levels of recreational use helps to discourage illegal activities like camping or dumping.

The future of the marsh depends on people being dedicated to it, Andre said.

"Over the years, people have to build an ownership so they can defend it from future impacts and compromises."

Williams agrees.

"It's the combination of political will and technical expertise that allowed Arcata to be so successful in wetlands restoration thus far," he said.

Looking forward to the McDaniel's Slough project, Williams says he hopes that "the same dynamic will be applied to this project."

BEDS & RELATIONSHIPS

by SHERI WOO

"I'm with you on the beds." -- ( Alex Horne to EPA's Jim Kreissl, agreeing that nitrogen is removed in gravel bed wetlands)

Gravel bed wetlands and the relationship between rate constants and temperature were two "hot" topics at the Conference on the Role of Wetlands in Watershed Management, held at Humboldt State University last month, and sponsored by HSU's department of environmental resources engineering. Robert Gearheart, HSU professor and design engineer of Arcata's much publicized sewage treatment wetland, and Arcata Mayor Connie Stewart, welcomed over 250 engineers, planners, resource agency administrators, biologists and botanists to the conference. Featured wetlands included those in Saipan and Palau, as well as those closer to home, such as the United Indian Health Village in Arcata.

Wetlands remove pollutants, on that all conference attendees agreed. But two schools of thought argued over computer modeling of wetlands removing pollutants. The Old School (wiser, more experienced engineers) cautioned the New School (code-writing programmers) to take care when modeling with rate constants.

A rate constant is a number that relates how fast (that is, the rate) a pollutant turns into something "safe." Say you've got a pile of rotten, stinky gym clothes, and you want to turn them into freshly scented shorts and T-shirts. How quickly this happens depends on the wash temperature (hot or cold cycle) and the right person for the job (Mom). In a laundry computer model, the rate constant depends on wash temperature and what kind of mother you have.

The Old School engineers warned the "youngsters" to select their rate constants more carefully, if they want their computer model wetlands to resemble real ones. Laundry by Martha Stewart is likely to be fresher and faster than laundry by Billy's three-martini-lunch mom.

The message was "when modeling laundry, don't use the Martha rate constant on Billy's clothes." Similarly, when modeling wetlands, don't use rate constants from wetlands in Southern California to describe wetlands in Manitoba.

Seems obvious, but New School engineers lamented the scarcity of rate constant data. Deriving rate constants can take weeks in the laboratory, and even then, laboratory data do not always translate to what happens in a real wetland.

Wetland water treatment systems are now very popular with municipalities and water districts. But city governments are loathe to pay for studies that would refine "details" like computer model rate constants. In these times of budget deficits and dual career families, sometimes the Billy's mom rate constant is the only one around.

Comments? E-mail the Journal: ncjour@northcoast.com

© Copyright 2000, North Coast Journal, Inc.