|

IN

THE NEWS | CALENDAR

by EMILY

GURNON

RECYCLING. IT'S GOOD FOR THE

ENVIRONMENT.

It stems the flow of garbage

to our landfills. It makes old things new. We can even collect

money for our recycling efforts.

Let's face it, recycling makes

us feel good. We don't have to toss that plastic Pepsi bottle

in the trash, knowing it will lie dormant in a landfill for eons.

And here in environmentally conscious Humboldt County, recycling

is The Thing to Do.

So when the recycling centers

in Arcata and Eureka recently began taking more of the numbered

plastics -- containers labeled 3 through 7, rather than just

the 1s and 2s -- it was welcomed as good news. As one state official

said, "Recycling is one of those things where more is always

better." But is it?

The recycling of plastic has

a dark side -- one little known to most consumers. The majority

of the plastics we recycle, regardless of type, end up in China,

where worker safety standards are virtually nonexistent and materials

are processed under dirty, primitive conditions. And the economics

surrounding plastic recycling -- unlike those for glass and aluminum

-- make it a dubious venture for U.S. companies.

Breathing fumes

I've

been in the [Chinese] factories and I can smell it," said

Jim Puckett, coordinator of the Seattle-based Basel Action Network,

a nonprofit group working to support the international agreement

on hazardous wastes called the Basel Convention. "It can

give you a headache almost instantly, and [the workers] are hovering

over this melting stuff all day." I've

been in the [Chinese] factories and I can smell it," said

Jim Puckett, coordinator of the Seattle-based Basel Action Network,

a nonprofit group working to support the international agreement

on hazardous wastes called the Basel Convention. "It can

give you a headache almost instantly, and [the workers] are hovering

over this melting stuff all day."

Puckett visited China in December

2001 when his organization was investigating the export of electronics

waste from the United States. While he was there, he also saw

recycling facilities that handled consumer plastics like soda

bottles and plastic bags.

"The ones we witnessed

were pretty bad," Puckett said. Since plastics are made

from petroleum, and since they must be melted down to be recycled,

"the concern is what the emissions exposure will be like,"

he said. The workers, who make about $1.50 a day, "are breathing

it indoors all day long." And some plastics additives, like

flame-retardants, can be toxic when heated, he said. No workers

he saw were wearing masks or other protective equipment. He also

observed labor practices that one would never see in the United

States -- such as small children going through bags of shredded

plastic for hours, sorting the tiny pieces by color.

[photo above right:

Plastic chipper (foreground) and melter unit (behind) in Chinese

recycling factory. Photo © Basel Action Network]

Even worse than the occupational

exposure may be the effect of plastics recycling on the environment

in China, Puckett said. "If stuff has a little bit of contamination

[such as an unidentifiable white dust], workers just dump

it in the countryside. We saw plastic bags floating around

in the fields."

Because plastics are not classified

as hazardous wastes, they are not regulated by international

law. But "from an environmental standpoint, they worry us

a lot," Puckett said.

Puckett readily admitted that

there has been little research on the potential health hazards

in the Chinese facilities or environmental dangers. There is

no information on the long-term health risks workers may be facing,

the number of workers involved, or the number of factories.

California, while pushing heavily

for the recycling of plastics, has not closely examined the conditions

under which the recycling takes place overseas.

"Right now, a lot of our

material is indeed baled and shipped off-shore," said Calvin

Young, market development specialist with the state Integrated

Waste Management Board. "We all hear the horror stories,

but there's not a lot of verified information" about working

conditions in China or elsewhere, he said. A spokeswoman for

the waste board, which manages California's solid waste stream,

said the state's hands are tied. "Once you release the material

and another person buys it, you can't tell them what to do with

it," said Roni Java.

Low conversion

rate

What is clear is that plastic

recycling presents myriad problems. In addition to safety and

environmental questions, technological and economic hurdles have

complicated plastics recycling efforts in the United States.

The result: Plastic containers get turned into new products at

a much lower rate than glass bottles or aluminum cans. The can

you recycle today, for instance, will make its way back to the

supermarket shelf in just six weeks. Because of health concerns,

a plastic bottle will never become another plastic bottle. Recyclers

often have a hard time making ends meet because the demand from

manufacturers for recycled plastic -- and, consequently, the

money paid for it -- is considerably less than for virgin material.

The plastics industry, of course,

has nothing but good things to say about the role of plastics

in our lives. They are "a responsible choice in a more environmentally

conscious world," according to the American Plastics Council,

the national trade association for the plastics industry and

the group responsible for the upbeat "Plastics Make It Possible"

ad campaign. Examples of how plastics "leave a lighter footprint

on the planet" include the argument that plastic grocery

bags are lighter and create less waste by volume than paper sacks,

the industry said. And the fact that plastics are so lightweight

and durable enables manufacturers to use less energy and generate

less waste in production processes, plastic promoters said.

The plastics industry also likes

to tout the many uses of recycled plastic, even publishing a

recycled products directory that lists everything from bookmarks

to boxer shorts to Dumpsters reportedly made with recycled plastic.

The state of California, meanwhile,

earnestly promotes recycling of plastic containers. The state

Department of Conservation announced last week that it is launching

a new campaign to raise public awareness of the growing mounds

of plastic bottles in our landfills and to promote recycling.

"The sight of a water bottle

in someone's hand has become as common as a cell phone,"

said Darryl Young, the department's director.

A proliferation

of plastic

Clearly, there is a dilemma.

Recycling presents problems, yet not recycling hardly seems

an option. Plastic is the fastest-growing portion of our waste

stream and now makes up the second-largest category by volume,

next to paper, of trash going into our landfills, according to

a draft report prepared for the California Integrated Waste Management

Board called the "Plastics White Paper."

Plastics make up 17.8 percent

by volume of what's thrown into California landfills (and 8.9

percent by weight). While consumers are increasingly snapping

those Evian bottles off the shelves, they toss the empties into

the trash bin more often than the recycling bin. The recycling

rate for plastic bottles is only 16 percent -- miserably low

compared to glass and aluminum -- even though consumers can redeem

their used plastic bottles for the same CRV (California Refund

Value) rate as other containers.

California cities and counties

have an incentive to recycle as much material as possible. A

1989 law requires that municipalities reduce the trash they send

to landfills by 50 percent by the year 2000 or face hefty fines.

(Many, like Arcata and Eureka, have received extensions to meet

the goal.)

Diversion, then, becomes the

magic word. But from the point of view of recyclers, accepting

some types of plastic is more trouble than it's worth. For example,

plastics coded 3 through 7 -- cottage cheese, tofu, salsa

and yogurt containers -- are particularly difficult to recycle

profitably. So why take these additional containers at all, especially

when their volume is low? According to Mark Loughmiller, executive

director of the Arcata Community Recycling Center, which also

manages the Hawthorne Street Recycling Center in Eureka, the

answer is public pressure.

"I fought it. There are

no domestic markets for it. At a point you get tired of being

harangued by people coming in trying to quote unquote `do the

right thing.'" They don't want to throw anything

away, he said, and that's all well and good. But a more appropriate

position might be, "I shouldn't buy it in the first place,"

he suggested.

The plastics trail

The plastics collected at the

Arcata and Hawthorne Street sites are baled and stored for about

a month until they fill a 12-ton truckload, Loughmiller said.

The truck typically contains 5 tons of milk bottles (the number

2s), 7 tons of soda and water bottles (the number 1s), and about

three-quarters of a ton of the so-called "mixed plastics,"

the 3s through 7s, which are baled together.

They then make their way to

Ming's Recycling in Sacramento (which also takes all of the plastics

from Humboldt Sanitation in McKinleyville). Kenny Luong, president

of Ming's, said his center has 40 or 50 suppliers in California

and another 30 to 40 elsewhere in the United States and Canada.

Almost all of the plastics that come into Ming's are sold to

brokers in Hong Kong, who pay to transport it via container ship

from the Port of Oakland to China. The transport is cheap because

China exports far more to the United States than we do to them;

the ships traveling back to China have plenty of room.

The mixed plastics don't make

Luong very much money, he said, which explains why the cities

of Arcata and Eureka get nothing for their mixed plastic bales.

(A ton of milk jugs, by contrast, pays about $200; a ton of soda

bottles, $160.)

"It's enough to cover the

transport to the harbor, that's pretty much it," Luong said

of the mixed plastics. He would prefer not to take those at all.

But a change to state law in 2000 expanded the list of beverages

included in the California Redemption Value program. And if the

bottle has a "CRV" on it -- even if it's a number 3

or 4 plastic -- a certified recycling center must accept it and

pay the refund to the consumer.

"It's really a pain in

the butt," Luong said. "There aren't a whole lot, but

we are required to purchase them by law. It prompted us to find

a market for it."

That market, it turns out, consists

of recyclers in Shanghai and Guangdong province. Luong said he

has never seen the China facilities and knows little about them.

"Once it's loaded on the ship, it's out of my hands."

Recycling in Guangdong

One of his brokers has visited

some of the locations in China where plastics from Humboldt end

up -- places similar to those that the activist from the Basel

Action Network saw. Doug Spitzer is the owner of Monarch

Enterprises of Santa Cruz, which is affiliated with the gargantuan

paper company Boise Cascade. He sells plastics to Chinese recyclers

and ran a plastic film-recycling factory himself outside of Guangdong

in the early 1990s.

"Most of our material goes

through Hong Kong into that closest province [to Hong Kong],

which is Guangdong," Spitzer said. One factory will typically

limit itself to one type of plastic, and one village might have

most of its residents involved in that type of recycling, he

said.

"Within this one town outside

of Guangzhou [in Guangdong province], when I was there, my partners

were telling me there were at least 3,000 plastic film processors

there, and they're right next door to each other. It's a small

village; they all process it." The facilities range from

a mom-and-pop operation that takes one container-load per month

to very large, comparatively modern factories.

One Spitzer saw when he visited

four years ago involved soda bottles: The workers would break

open the bales, women would sort the bottles by color, a "guy

with a machete" cut the tops off, two other men scraped

labels off, then the bottles were ground into pellets and melted

down.

It was not the kind of place

that would be approved by the U.S. Occupational Safety and Health

Administration, Spitzer said.

"OSHA would go nuts. The

place is noisy, it's crowded, it's just amazing. Not that they're

killing people off. They're safe, and all the time we were running

the factory there were no major accidents," he said. "Do

people engage in unsafe practices to try to make a living? Yeah,

all over the world."

He said his current business

provides a valuable service. "What I'm doing is I'm supplying

a raw material that can go to a Third World country."

There are some facilities in

the United States that recycle soda bottles and milk jugs "if

the material is clean enough," said Luong of Ming's Recycling.

But the market for recycled plastic makes it difficult, if not

impossible, for recyclers to make any money. The reasons are

many. Since plastic is made from petroleum, virgin plastic makers

have a large supply of raw material available to them. When manufacturers

can buy virgin plastic pellets or flakes for about the same amount

of money as recycled plastic, there is little incentive to use

recycled.

There are also limits to the

products that can be made from recycled plastic. The U.S. Food

and Drug Administration does not allow food containers to be

made into new food containers because they can't be heated at

temperatures high enough to sterilize them. (The FDA has said

it will allow a layer of recycled plastic sandwiched between

layers of virgin plastic in soda bottles.)

A numbers game

Plastic recyclers must also

face the issue of contamination. Recycling the number 1 (PET)

plastics -- the soda bottles -- could work economically were

it not for the number 3s that enter the mix, said Peter Anderson,

a recycling consultant in Madison, Wis., who has worked with

state and federal agencies, including the U.S. Environmental

Protection Agency and the state of California. Number 3 plastics

are polyvinyl chloride, or PVC for short.

"PVC presents enormous

problems because it looks just like PET physically," Anderson

said. "A single bottle of PVC will contaminate the entire

[10,000-bottle] load" aesthetically, causing the new PET

bottles made with the material to be yellowed or, with more contamination,

to have black streaks, he said. There are X-ray scanning machines

that can detect the PVC intruders, but those are too expensive

for many recyclers.

"You can't make plastics

recycling work with PVC in the mix," Anderson said. So,

he argued, taking the 3 through 7 plastics makes no economic

sense. "Who the hell knows what China's doing with them?

I don't think anyone can make a case without a smirk on their

face that they're recycling 3 through 7s."

He called the idea of recycling

all plastics "a serious mistake."

Some recyclers take the 3 through

7 plastics because, they reason, they'll get more of the "good

stuff" -- the soda bottles and milk bottles -- if they advertise

that they accept a wider range of recyclables. Eel River Disposal

in Fortuna, for example, accepts numbers 1, 2 and 3, which they

send to Smurfit Recycling in Oakland.

Eel River owner Harry Hardin

said he doesn't collect enough of the number 3s to make a separate

bale with it, so he bales it with the number 2s. "I even

put some 4s in there," he said.

Asked about the PVC contamination

problem, Hardin said, "It depends what market you send it

into. Smurfit's -- I'm not quite sure what they do with theirs.

But they will allow some number 3 and 2 together."

Not so, said Don Kurtz, plant

manager for Smurfit in Oakland. "If we identify that there

are 3s in there, we reject the bale," he said. Eel River

was recently told to come and get one of their bales that was

turned away for that very reason. "We really don't want

number 3s. It really doesn't make sense for us to mess with it."

(Unlike Ming's, Smurfit is not legally bound to take any particular

recyclables because the company is classified as a "processor,"

not a recycling facility.)

Another Humboldt County recycler

sells his material to a middleman in a different part of the

state. The man, who did not want to be identified, said he does

not collect enough 3 through 7 numbered plastics to bale them

separately, so he mixes them with the bales for the numbers 1

and 2. "Don't advertise that," he said. "It's

garbage plastic, but a lot of people like to recycle it."

His company then sells it to a broker who sends it overseas.

"If they're putting it

in with the PET [number 1s], I guarantee they're getting thrown

out," said the broker, Patty Moore of the Sonoma-based Moore

Recycling Associates.

Destination landfill

All in all, plastic recycling

appears to fall far short of its promise. Even if recycled under

the best of conditions, a plastic bottle or margarine tub will

probably have only one additional life. Since it can't be made

into another food container, your Snapple bottle will become

a "durable good," such as carpet or fiberfill for a

jacket. Your milk bottle will become a plastic toy or the outer

casing on a cell phone. Those things, in turn, will eventually

be thrown away.

"With plastics recycling,

we're just extending the life of a material. We're not creating

a perpetual loop for that material," like we do with glass

and aluminum recycling, said Loughmiller, the Arcata recycling

director.

"I think people really

need to have a reality check on plastics," said Puckett

of the Basel Action Network. "The mantra has been, `divert

from the landfill.' What we've been saying is, divert to what?

Dump it on the Chinese? Plastics recycling needs to be looked

at with a jaundiced eye," he said. "It's not what it's

touted to be."

![[symbol] means recyclable, right?](cover0605-recyclehed.jpg)

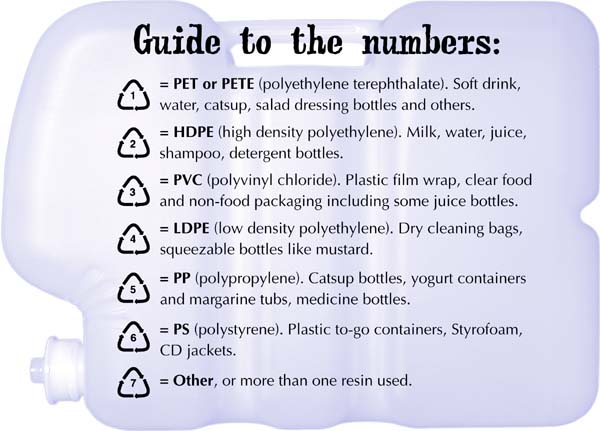

IF YOU'VE EVER LOOKED ON THE

BOTTOM OF YOUR PLASTIC JUICE BOTTLE, detergent bottle or tofu

tub, you've seen the little triangle of arrows with a number

inside. That symbol -- contrary to popular belief -- does not

indicate that a container is recyclable.

Back in 1988, "the trade

groups managed to get into law the resin [type of plastic] identification,"

said Mark Loughmiller, executive director of the Arcata Community

Recycling Center. The numbers indicate which category of plastic

the container is made from.

"The triangled arrows imply

recyclability," Loughmiller said. "The plastic industry

denied it was trying to mislead the public and cause confusion."

But that's what happened, he said. People regularly come to his

center and demand to know why their plastic lawn chair with a

number on the bottom can't be recycled.

And why can't it? Because, even

in one category, such as plastics labeled with a number 2 (high

density polyethylene or HDPE), there are many variations. Milk

jugs and yogurt containers, for example, may both be made with

HDPE, but because the recycling process requires melting of the

old containers, and they melt at different temperatures, they

may be incompatible.

Redway operation

turning milk jugs into planters

Not all of Humboldt County's

plastics travel hundreds or thousands of miles before they are

recycled. Some of them go to R&R Auto Machine in Redway,

where Tom Hoffman and John Schwarz make them into planter boxes

(when Hoffman is not operating heavy equipment and Schwarz is

not repairing motorcycles, that is).

The two entrepreneurs have used

more than 800 pounds of plastic milk bottles to make 10,000 planters

in the year they've been working on the project.

"We don't make any more

money than we would if we just used virgin plastic," Hoffman

said, "but we like to recycle. It's part of the future."

Their operation emits no pollution

and is not dangerous, Hoffman said. "It's a completely self-contained

system."

The planters are available at

the Arcata Community Recycling Center and American Hydroponics

in Arcata."

From the left, recycled

plastic from milk jugs after going through the chipper;

Tom Hoffman pours plastic particles into melter and the finished

planter box below.

IN

THE NEWS | CALENDAR

Comments?

© Copyright 2003, North Coast Journal,

Inc.

|