|

IN

THE NEWS | CALENDAR

by WILLIAM SEVERINI KOWINSKI

by

WILLIAM SEVERINI KOWINSKI

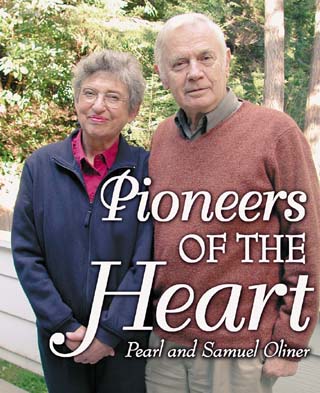

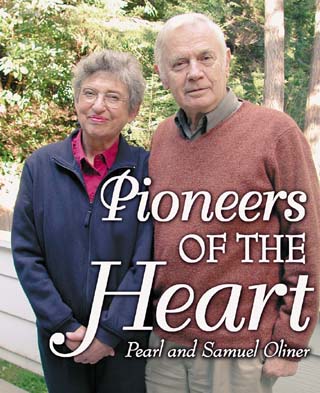

THEY LIVE ON A CALM HILL IN

SUNNY BRAE, WITH Humboldt Bay barely visible through the veil

of trees across the street. In their early 70s, Pearl and Samuel

Oliner are retired from teaching at Humboldt State University

(she is a professor of education, he of sociology.) But their

apparently quiet life is deceptive. They are pioneers in an ever-expanding

field of inquiry that is changing how human nature is perceived,

and may yet help to create a more caring, peaceful future. And

they're still working at it.

The Oliners are among the remarkable

number of local residents who play an important role in the world

beyond Humboldt County. In their case, they helped start something

like a continuing international revolution in academic thought,

with implications for how we all see ourselves. They began it

with a question.

Why did they do it? That was the question. Why did they risk everything

-- their safety, their lives, even their families -- for strangers?

But some did: they harbored those they were forbidden to help,

by aiding Jews escaping from the Nazis in World War II. At other

times and places, they leapt into rivers to pull drowning strangers

from cars being sucked to the bottom. They ran into the devastated

Twin Towers to lead others to safety on Sept. 11. But why? Why

did they do it?

For a long time the question

wasn't even asked. Some individuals were honored as heroes and

saints, but that was all, as if what they did wasn't really human.

They embarrassed the experts, because what they did ran counter

to every prevailing explanation for human behavior, from philosophy

and theology to biology, psychology, economics and the social

sciences. Self-interest, rational choice, the struggle for

survival, original sin, the dark unconscious -- there was

no room anywhere for altruism.

Auguste Comte, the father of

sociology, coined the term in the mid-19th century, but altruism

-- unselfish behavior on behalf of another -- soon sunk out of

sight. Today it's an academic growth industry. Scholars from

all the above-mentioned fields are struggling to answer that

question, why did they do it? Because once it was seriously

asked, and addressed in a systematic way, it became the elephant

in the halls of ivy: It couldn't be ignored. Altruistic behavior

calls all those explanations into question, and it begins to

suggest new ways of examining what being human is all about.

Now those answering that question

are part of a movement to find out what's right with human nature

as well as what's wrong, to discover why and how we can cooperate

as well as compete, be compassionate as well as egotistical,

and devise, learn and use the skills of peace as well as the

skills of war.

And in an irony that is inescapably

part of the inquiry, this contemporary search for the sources

of good began in response to an historic eruption of evil: the

Holocaust.

RESTLESS MEMORIES

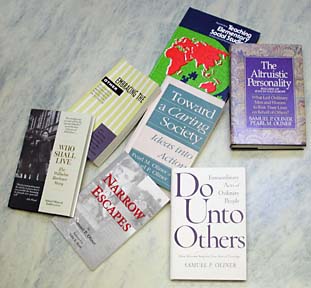

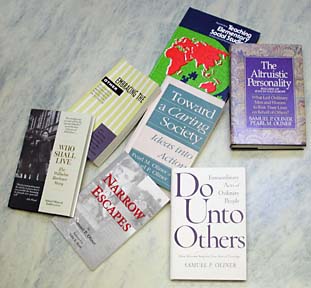

He has told the story many times:

a third-person account in his first book with Pearl, The Altruistic

Personality, a first-person narrative in his new book, Do

Unto Others: Extraordinary Acts of Ordinary People, and at

length in his memoir, Restless Memories. It is always

powerful and always vivid.

Samuel Oliner was 12 when the

Nazis raided the ghetto in southern Poland where he and his extended

family had been forced to live. His stepmother told him to run

and hide. By the end of the day, everyone in the ghetto was gone.

Only Samuel, hiding on the roof, remained.

In these accounts he remembers

with seemingly uncanny precision every moment, every emotion,

every sight and smell of that day. Neuroscientists are familiar

with this phenomenon: It is common when someone experiences intense

fear. Every perception is heightened, every moment lengthens.

The memory of it all remains inescapably clear for a very long

time.

Already resourceful, he made

his way out of the ghetto and into the countryside. He took a

chance and asked a farmer for bread. As they walked from the

field to the house, the farmer chatted about the Nazi raid. They

took all the Jews into the woods and shot them, he said. Samuel

could not reveal the intensity of his emotions, only a boy's

curiosity about the mechanics of death. He asked how they could

kill so many. With machine guns, the farmer told him. It took

them all day.

He wandered the countryside

for days, until hunger and the risk of being in the open forced

him to seek out someone in a nearby village who had known his

family. When he knocked on their door, he faced the possibility

of being turned over to the Germans. Instead the woman who opened

it hugged him, and gave him a home.

He learned to pass as a non-Jew,

and survived the next three years until the war ended. Then,

with some Jewish survivors, he sneaked into Czechoslovakia. On

his way to West Germany, he met his first black man -- an American

GI who saw him hitchhiking and gave him a ride.

A postwar program relocating

war orphans got him to England, and a Jewish network for finding

relatives willing to sponsor immigrants got him to an Oliner

in New Jersey. He was there less than a year when in 1951 he

was drafted into the U.S. Army, as part of a Korean War program

that would grant him citizenship in exchange for his two-year

hitch.

Oliner went to the extent of

learning German to get posted to Europe but still he was sent

to Korea, where he guarded prisoners of war. His most dangerous

moment, he recalls, was the flight east from Seattle upon his

return, which ended in a belly flop landing in Montana.

But he eventually got to New

York, the GI Bill got him started in college, and the wife of

a married army buddy set him up with her friend on a blind date.

Not much more than a year later, he and Pearl were married.

New York was exciting but a

struggle, and then Sam told Pearl about the sunny expanses of

California. He'd seen it on his way to Seattle to ship out to

Korea, and she'd never been there at all. But the friends who

had introduced them were there, and so they arranged to go: Pearl

became the principal of a school in Oakland, and Sam would get

his master's at San Francisco State University. Some years and

three sons later (as well as several academic degrees each),

Sam got a one-year appointment at Humboldt State. They arrived

in the rain. But they stayed anyway.

TEACHING ABOUT EVIL

The past seemed safely tucked

away, but by the early 1970s Sam Oliner was alarmed by a wave

of Holocaust denying: The systematic murder of European Jews

had never happened, some people were claiming, and that horrific

footage shot by Americans liberating concentration camps was

all faked. Not many were saying this, but it was easy enough

to see that this is how it could all get started again. Outright

lies about the Jews in World War I became the seedbed of fascism

in Germany in the 1920s and `30s. So Oliner and colleagues at

HSU began teaching one of the first college courses in America

on the Holocaust.

In a century of unparalleled

destructiveness, the horrors of the Nazi concentration camps

suggested a human capacity for evil beyond ordinary expectations.

The experience of American writer Susan Sontag, recalled just

a few weeks ago in an interview with Bill Moyers, was widely

shared: She was 12 when she first saw pictures of Dachau and

Bergen Belsen as they were liberated in 1945. "I suddenly

thought, `Oh my God. This is what human beings can do to other

human beings.' I could say that my whole life is divided into

before I saw those pictures and after."

Sam Oliner taught the evils

of the Nazis and of anti-Semitism. He studied and taught the

evils of racism, homophobia and other oppressions. Later he would

begin one of the first courses in the nation on genocide, with

Native American Studies professor Jack Norton, who applied the

concept to the attempted eradication of native peoples in Northern

California.

But in the early 1980s, something

happened while Oliner was teaching the Holocaust course. After

one of the first sessions of the term, a young woman came to

him in tears. She was German, married to an American student.

She had to drop the course, she told him, because it was too

painful to hear "what my people did to your people."

"I was moved by this,"

Oliner recalled. "First of all, she had nothing to do with

it, she was innocent. But her pain got me thinking. What else

can we teach besides horrors and murder and torture? What else

can we learn?"

He remembered the family that

had helped him evade the Nazis and survive the war, at great

risk to themselves. He began thinking about them in a new way.

The Israeli government had begun

to officially honor rescuers, and some stories of rescue turned

up in memoirs. But there was very little scholarship, and almost

nobody was going deep enough to begin asking that essential question,

the one that might lead to deriving some greater meaning, perhaps

even a way to encourage such altruistic behavior in the future:

Why did they do it?

It was the question nobody knew

how to answer, especially when applied to Holocaust rescuers.

It was about this time that an award-winning screenwriter got

in touch with Annette Insdorf, author of Indelible Shadows:

Film and the Holocaust, the best known and most complete

book on the subject (she tells this story in the revised 2003

edition). The screenwriter wanted to write a movie about Oskar

Schindler and his rescue of more than a thousand Jews, but he

couldn't figure out how to handle the question of Schindler's

motivation. Why had he done it? "Neither of us could find

a sufficiently satisfying answer," Insdorf writes. Both

her parents were Holocaust survivors. A few years later, Steven

Speilberg solved the problem of "why" by more or less

ignoring it. In Schindler's List, Schindler's motives

remain mysterious. Even in this year's hit film about the Holocaust,

The Pianist, the rescuers' reasons are mostly implied

or obscure.

Why this question should be

so puzzling is easy to explain, though it may be hard to face.

Evil might be shocking, and the motives of informers and bystanders

might be shameful, but just about every discipline can supply

a reason for such behavior. Beginning with Plato, the mainstream

of western philosophy maintains that people naturally act in

their own interest, an approach refined and applied to economics

and political science. The dominant interpreters of Darwin approve:

Even our genes are selfish. "Look out for No. 1" is

a law of nature as well as an axiom of common sense, explaining

if not always fully justifying every conceivable evil and indifference,

from the white lie to the black market, from not getting involved

to genocide.

Add the explanations for malevolence

by the unlikely tandem of Freud and the Bible (Freud suggested

dark drives in the unconscious that seemed to express the sinful

state of humanity ejected from Eden) and it all seemed awful,

but also the way we are.

But the family that saved Sam

Oliner seemed human, too, even though they were acting against

their own interests. Maybe it was time to look at good as well

as evil in human beings, and perhaps the place to start was with

the people who risked everything for others, at a time when everything

was being taken away from those others.

It would be a huge task. Oliner

began looking around for help. He didn't have to look far.

THERE SHOULD BE JOY

Pearl Merkur grew up in the

tenements of Brooklyn, where the Jewish neighborhood was next

to the black neighborhood, and they were all poor. She was an

excellent student who earned degrees from Brooklyn College and

the Jewish Theological Seminary at the same time. She loved the

intellectual atmosphere at her college and in the cafes of Greenwich

Village, and she got involved in social causes, particularly

the early `50s issues that would soon become the Civil Rights

movement. Pearl knew about the Holocaust, but it seemed a part

of the past compared to the searing issues of the day. Besides,

she didn't want to be buried in sorrow, under the heaviness of

Jewish history. There should be joy in life, too.

As she began her professional

career, Pearl Oliner had similar reactions to the one-sidedness

of education theory and the teaching of social sciences, her

principal area of interest. The prevailing wisdom was that education

should develop rationality, with little regard for feelings.

She was also told that if research into social subjects was going

to be real science, it would have to be as rigid and quantitative

as physics.

Pearl Oliner believed in scientific

analysis, but was still wary of what social science was leaving

out. People had feelings, and they were important. So she began

tentatively adding elements of emotion and of qualitative research

-- that is, stories -- to her work. The title of her first book

reflected this duality: "Teaching Elementary Social

Studies: a Rational and Humanistic Approach."

By the time she had secured

a full-time position at Humboldt State, her views on the Holocaust

had matured, thanks in part, of course, to her husband. But when

child development expert Paul Henry Mussen spoke at HSU, he used

an expression she'd never heard before: "pro-social behavior."

It turned out nobody had heard

it before; one of Mussen's graduate students had invented it,

as the opposite of "anti-social behavior." It was behavior

that made things better, that contributed to the common good.

It said what Pearl Oliner had been searching for without necessarily

knowing it. She could combine the rational with something hopeful,

something to do with the heart.

She had written articles on

pro-social behavior when Sam suggested that they work together

on a research project, investigating altruism among rescuers.

They would be looking at compassion in an extreme form, when

its cost could be fatal. It was a major commitment, professionally

and personally. But despite the dangers inherent in a couple

combining work with marriage, there was a certain logic to it.

It seemed that their separate journeys had come to the same point.

Besides, it would only take

10 years.

WHY DID THEY DO IT?

In some ways, what they wanted

to do seemed crazy. How do you study compassion, or quantify

goodness? But they believed that the tools of social science

would help illuminate that basic question: Why did they do

it? So with the support of grants and the participation of

graduate students and colleagues at HSU and elsewhere, the Oliners

designed detailed questionnaires for rescuers of Jews in World

War II and a control group of bystanders, and interviewed some

800 people in seven countries.

They correlated variables, they

ranked responses and they listened to the voices telling stories.

Their findings were complex and detailed, but a few impressions

jumped out. Few rescuers sought fame or reward, but none regretted

what they did. Some had forged papers and smuggled Jews to safety.

They lied to Nazi officials and their neighbors, and a few committed

acts of violence. For some, these activities went on for years.

But almost all of them professed something close to astonishment

that anyone had to ask why they did it. They said that of course

they didn't have to do it, but at the same time, they had no

choice.

Some said it was what their

parents taught them, or what their faith or ethical code dictated.

Some said it was just the natural thing to do.

Why did they do it? Because strangers in trouble were still people

in trouble who needed their help. Because their hearts and sometimes

even their heads told them it was the right thing for them to

do, that if they didn't, they would damage or even lose the essence

of themselves.

There could hardly be a more

shocking conclusion, at least to the many scholars and scientists

who still can't figure it out or even accept it. But for others

this study opened a door, and on the other side of it is the

possibility of a new way to think about humanity and perhaps

even the universe. It isn't the only such door, but it is one

that is now wide open, and other explorers are eagerly stepping

through it.

"The Oliners' work was

so careful and so broadly based that it opened the field,"

says Kristen Renwick Monroe, professor of politics at the University

of California, Irvine, and author of The Heart of Altruism.

"It gave us a much more sophisticated understanding of the

altruistic personality, and made our knowledge much deeper, closer

to the root of it. People like me are very deeply indebted to

them."

By the time the Oliners were

finishing their research, editors at the Free Press had heard

about it and asked them to write a book. The Altruistic

Personality was published in 1988. It led to dozens of speaking

invitations -- "People need hope," as Pearl Oliner

said -- then to an international conference on altruism in Poland.

That led to a collection of studies presented there, which the

Oliners edited along with four other scholars, published as Embracing

the Other.

They authored an essay for this

anthology that suggested lessons from their research that could

be applied to fostering pro-social behavior. That essay soon

led to another book they co-authored, called Toward A Caring

Society, which offers practical lessons on encouraging compassion,

empathy, caring behavior and the peaceful resolution of conflict.

[see sidebar at bottom of page]

Their work continues. They established

the Institute for the Study of Altruism and Pro-Social Behavior

at HSU. Sam Oliner's new book, Do Unto Others, published

last month by Westview Press, expands beyond the rescuers and

health workers in previous studies to examine ordinary people

who performed heroic acts for others, including heroes of Sept.

11, soldiers, and people who risked their lives at accident scenes

or during a race riot. Next year, Yale University Press will

publish Pearl Oliner's new book, tentatively titled Outsider

as Insider: Religious Culture and the Rescue of Jews in Nazi

Europe.

They continue to share their

work with HSU and the community. Sam Oliner recently spoke at

the annual Diversity Workshop and the North Coast Education Summit

on campus, and Pearl set the framework for discussion at the

"Building Communities That Care" workshop, co-sponsored

by the Growing Caring Communities Alliance and the HSU sociology

department.

Meanwhile, the field is expanding

all around them. Many social and political theorists are

appraising the evidence of altruism. While the anthology the

Oliners edited a decade ago contained contributions in

seven or so disciplines, mostly within social studies, a similar

anthology published in 2002 (Altruism and Altruistic Love)

contains essays by scholars in at least 16 different disciplines,

including evolutionary biology, neuroscience and biomedical ethics.

Now biologists can look at animal

cooperation and the fundamental role of symbiosis from a different

perspective. A prominent neuroscientist believes that human reason

requires feeling, and ethics regulated by emotions are necessary

to evolutionary success. A theoretical physicist wonders if there

might be something he calls "quantum empathy."

Even psychology no longer dwells

exclusively on individual illness and bad behavior. There's a

new Center for the Development of Peace and Well-Being at the

University of California, Berkeley, that sponsors research

focusing "on what contributes to the greater good,"

according to its director, Dacher Keltner. There's a broad new

movement called positive psychology, and another called peace

psychology. Teaching compassion has become part of the curriculum

in many schools at all levels.

The Oliners were part of starting

all this. Despite the skeptics, "altruism exists,"

Sam Oliner maintains. "It can be taught, it can be cultivated.

If the Holocaust is western civilization's nightmare, then helping,

caring and compassion are our hope."

William Severini Kowinski

is a freelance writer based in Arcata. He is the author of The Malling of America.

|

A HITCHHIKER'S GUIDE

TO CARING

The eight elements of caring described

in Toward a Caring Society, by Pearl M. and Samuel P.

Oliner

|

The "attaching" processes:

1. BONDING: Forming

positive connections to places and people. Bonding environments

often meet basic needs (e.g., the kitchen) and include formal

or informal rituals.

DO: Create or take advantage of opportunities to share with others,

even if it's as simple as a meal. Understand that forming bonds

takes time, attention and commitment.

DON'T: Smother individuality, or set insiders against outsiders.

Don't be phony just to be part of the group, or insist that others

meet all your expectations.

2. EMPATHIZING: Understanding others' feelings.

Empathy arises from awareness of others' situations, and from

common experiences.

DO: Know yourself, so you can imagine the role of another without

losing your identity.

DON'T: Decide you know what others need. Ask them!

3. LEARNING/CARING NORMS: Learning the responsibilities

and expressions of caring, especially from parents, is often

a crucial factor in altruistic and compassionate behavior.

DO: Teach your children a few positive caring concepts that can

be applied to a wide variety of situations. Talk about the reasons

for fairness and compassion. Encourage balance between doing

for others and doing for themselves.

DON'T: Rely only on rules or punishment. Accentuate what's right

rather than what's wrong.

4. PRACTICING CARE: From common courtesy to careers

in helping professions, taking care of others, empowering them.

DO: Learn to listen and respond.

DON'T: Feel guilty when you have to pull back. Care involves

choices. |

The

"including" processes:

5. DIVERSIFYING: Making an effort to know different kinds

of people.

DO: Overcome cultural distortions by engaging in common experiences

with others.

DON'T: Think you know everything about another culture after

one encounter.

6. NETWORKING: Working together with others on

something you have in common. Networks can be teams that work

together every day, or groups connected only by the Internet.

DO: Identify stakeholders in a common agenda. Think holistically,

share information.

DON'T: Let pursuing the goal override caring behavior.

7. RESOLVING CONFLICTS: Learn and use skills and

strategies to solve problems without force or intimidation.

DO: Learn the skills to transform enemies into partners in a

solution that meets everyone's needs.

DON'T: Assume all conflict is bad. Some conflict leads to creativity.

Don't avoid problems address them.

8.ESTABLISHING GLOBAL CONNECTIONS: "Linking the here

and now with people and places far and wide throughout the planet

in the service of care."

DO: Seek out ways to connect what you do with benefits to the

larger world to society, the environment, the future.

DON'T: Go crazy because you can't change the world overnight.

Don't lose sight of caring by getting lost in power games. |

IN

THE NEWS | CALENDAR

Comments?

© Copyright 2003, North Coast Journal,

Inc.

|